Abstract

Purpose

Previous research on the labeling perspective has identified mediational processes and the long-term effects of official intervention in the life course. However, it is not yet clear what factors may moderate the relationship between labeling and subsequent offending. The current study integrates Cullen’s (Justice Q 11:527–559, 1994) social support theory to examine how family social support conditions the criminogenic, stigmatizing effects of official intervention on delinquency and whether such protective effects vary by developmental stage.

Methods

Using longitudinal data from the Rochester Youth Development Study, we estimated negative binomial regression models to investigate the relationships between police arrest, family social support, and criminal offending during both adolescence and young adulthood.

Results

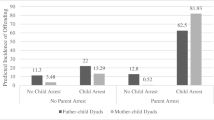

Police arrest is a significant predictor of self-reported delinquency in both the adolescent and adult models. Expressive family support exhibits main effects in the adolescent models; instrumental family support exhibits main effects at both developmental stages. Additionally, instrumental family support diminishes some of the predicted adverse effects of official intervention in adulthood.

Conclusions

Perception of family support can be critical in reducing general delinquency as well as buffering against the adverse effects of official intervention on subsequent offending. Policies and programs that work with families subsequent to a criminal justice intervention should emphasize the importance of providing a supportive environment for those who are labeled.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Examples of microlevel social support include positive relationships with parents, a partner, teachers, or friends. At the macrolevel, individuals may receive assistance from a variety of neighborhood organizations, and state and national welfare programs or charities.

People may also learn to deliver support to others, which can “transform selves, inculcate idealism, foster moral purpose, and create longstanding interconnections—all of which would seem anti-criminogenic” ([21], p. 543).

It is worth mentioning that empirical evidence for social support theory at the macrolevel is less consistent.

Conventional peers could also be an important source of support in preventing “secondary deviance” following official intervention across the life course. However, the RYDS data cannot differentiate between conventional peer support from delinquent peer support. Given the high-risk nature of the sample, we decided to focus on the protective effects of family support. We also recognize that faith-based organizations and other community groups may provide social support that moderates the criminogenic, stigmatizing effects of official intervention on offending. Unfortunately, we do not have detailed information on these organizations.

Individuals who were arrested between waves 1 and 6 were excluded from the adult models. By controlling for prior delinquency and other theoretically informed covariates at wave 6, we reduced the risk of spuriousness. Yet, it is worth mentioning that the same substantive findings were observed when we included those subjects and estimated the effects of arrests in waves 1–12.

As robustness checks, we also created (1) a continuous variable measuring the frequency of arrests, (2) an ordinal variable collapsing the frequency of arrests into categories, and (3) an ordinal variable accounting for the period of time between last arrest and later delinquency/crime. The results showed that the continuous variable was not a significant predictor of later offending in either the adolescent or adult models; we suspect that the continuous variable underestimated the labeling effects because it failed to capture the substantial differences between individuals with no record of arrest at all and individuals with any record of arrest. On the other hand, the conclusions drawn from using the binary indicator and the two ordinal measures were very similar (the Spearman’s rho was above 0.95 between each pair of comparison conditions). Specifically, both ordinal variables were significant predictors of later offending and instrumental family support lessened some of the predicted adverse effects of official intervention during adulthood. However, due to the statistical power provided by the ordinal variables, the high-risk categories often had relatively large incidence rate ratios (IRR), but with marginal or no statistical significance. Given that the same substantive findings were observed and for the clarity of argument, we present the final results from using the binary indicator of police arrest.

The correlation equals 0.65 in adolescence and 0.69 in early adulthood.

References

Hirschi, T. (1980). Labeling theory and juvenile delinquency: an assessment of the evidence. In W. R. Gove (Ed.), The labeling of deviance: evaluating a perspective (pp. 181–204). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Tittle, C. R. (1980). Labeling and crime: an empirical evaluation. In W. R. Gove (Ed.), The labeling of deviance: evaluating a perspective (pp. 241–263). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Bernburg, J. G. (2009). Labeling theory. In M. D. Krohn, A. J. Lizotte, & G. P. Hall (Eds.), Handbook on crime and deviance (pp. 187–208). New York: Springer.

Ciaravolo, E. B. (2011). Once a criminal, always a criminal: how do individual responses to formal labeling affect future behavior? A comprehensive evaluation of labeling theory (Doctoral dissertation). College of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Florida State University.

Hay, C., Stults, B., & Restivo, E. (2012). Suppressing the harmful effects of key risk factors: results from the Children at Risk Experimental Intervention. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39, 1088–1106.

Krohn, M. D., & Lopes, G. (2015). Labeling theory. In M. D. Krohn & J. Lane (Eds.), The handbook of juvenile delinquency and juvenile justice (pp. 312–330). Malden: Wiley.

Liberman, A. K., Kirk, D. S., & Kim, K. (2014). Labeling effects of first juvenile arrests: secondary deviance and secondary sanctioning. Criminology, 52, 345–370.

Morris, R. G., & Piquero, A. R. (2013). For whom do sanctions deter and label? Justice Quarterly, 30, 837–868.

Wiley, S. A., Slocum, L. A., & Esbensen, F. A. (2013). The unintended consequences of being stopped or arrested: an exploration of the labeling mechanisms through which police contact leads to subsequent delinquency. Criminology, 51, 927–966.

Lemert, E. M. (1951). Social pathology: a systematic approach to the theory of sociopathic behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Barrick, K. (2014). A review of prior tests of labeling theory. In D. P. Farrington & J. Murray (Eds.), Labeling theory: empirical tests. Advances in criminological theory (18th ed., pp. 89–112). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Paternoster, R., & Iovanni, L. (1989). The labeling perspective and delinquency: an elaboration of the theory and assessment of the evidence. Justice Quarterly, 6, 359–394.

Ageton, S. S., & Elliott, D. S. (1974). The effects of legal processing on delinquent orientations. Social Problems, 22, 87–100.

Bartusch, D. J., & Matsueda, R. L. (1996). Gender, reflected appraisals, and labeling: a cross-group test of an interactionist theory of delinquency. Social Forces, 75, 145–176.

Bernburg, J. G., & Krohn, M. D. (2003). Labeling, life chances, and adult crime: the direct and indirect effects of official intervention in adolescence on crime in early adulthood. Criminology, 41, 1287–1317.

Chiricos, T., Barrick, K., Bales, W., & Bontrager, S. (2007). The labeling of convicted felons and its consequences for recidivism. Criminology, 45, 547–581.

Harris, A. R. (1976). Race, commitment to deviance, and spoiled identity. American Sociological Review, 41, 432–442.

Klein, M. W. (1986). Labeling theory and delinquency policy: an experimental test. Criminal Justice & Behavior, 13, 47–79.

Lofland, J. (1969). Deviance and identity. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Jackson, D. B., & Hay, C. (2013). The conditional impact of official labeling on subsequent delinquency: considering the attenuating role of family attachment. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 50, 300–322.

Cullen, F. T. (1994). Social support as an organizing concept for criminology: presidential address to the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences. Justice Quarterly, 11, 527–559.

Makarios, M. D., & Sams, T. L. (2013). Social support and crime. In F. T. Cullen & P. Wilcox (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of criminological theory (pp. 160–187). New York: Oxford University Press.

Braithwaite, J. (1989). Crime, shame, and reintegration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Link, B. G., Cullen, F. T., Struening, E., Shrout, P. E., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (1989). A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. American Sociological Review, 54, 400–423.

Matsueda, R. L. (1992). Reflected appraisal, parental labeling, and delinquency: specifying a symbolic interactionist theory. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 1577–1611.

Sherman, L. W. (1993). Defiance, deterrence, and irrelevance: a theory of the criminal sanction. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 30, 445–473.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1997). A life-course theory of cumulative disadvantage and the stability of delinquency. In T. P. Thornberry (Ed.), Developmental theories of crime and delinquency. Advances in criminological theory (7th ed., pp. 133–162). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Harris, P. M., & Keller, K. S. (2005). Ex-offenders need not apply: the criminal background check in hiring decisions. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 21, 6–30.

Johnson, L. M., Simons, R. L., & Conger, R. D. (2004). Criminal justice system involvement and continuity of youth crime: a longitudinal analysis. Youth & Society, 36, 3–29.

Krohn, M. D., Lopes, G., & Ward, J. T. (2014). Effects of official intervention on later offending in the Rochester Youth Development Study. In D. P. Farrington & J. Murray (Eds.), Labeling theory: empirical tests. Advances in criminological theory (Vol. 18, pp. 179–208). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Lopes, G., Krohn, M. D., Lizotte, A. J., Schmidt, N. M., Vásquez, B. E., & Bernburg, J. G. (2012). Labeling and cumulative disadvantage: the impact of formal police intervention on life chances and crime during emerging adulthood. Crime & Delinquency, 58, 456–488.

Pager, D. (2003). The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology, 108, 937–975.

Restivo, E., & Lanier, M. M. (2015). Measuring the contextual effects and mitigating factors of labeling theory. Justice Quarterly, 32, 116–141.

Schmidt, N. M., Lopes, G., Krohn, M. D., & Lizotte, A. J. (2015). Getting caught and getting hitched: an assessment of the relationship between police intervention, life chances, and romantic unions. Justice Quarterly, 32, 976–1005.

Berk, R., Campbell, A., Klap, R., & Western, B. (1992). The deterrent effect of arrest in incidents of domestic violence: a Bayesian analysis of four field experiments. American Sociological Review, 57, 698–708.

Sherman, L. W., Schmidt, J. D., & Rogan, D. P. (1992). Policing domestic violence: experiments and dilemmas. New York: Free Press.

Sherman, L. W. (2014). Experiments in criminal sanctions: labeling, defiance, and restorative justice. In D. P. Farrington & J. Murray (Eds.), Labeling theory: empirical tests. Advances in criminological theory. Volume 18 (pp. 149–176). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology, 30, 47–86.

Chamlin, M. B., & Cochran, J. K. (1997). Social altruism and crime. Criminology, 35, 203–227.

Shaw, C., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lin, N. (1986). Conceptualizing social support. In N. Lin, A. Dean, & W. Ensel (Eds.), Social support, life events, and depression (pp. 17–30). Orlando: Academic.

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 145–161.

Uchino, B. N. (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: a life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 236–255.

Vaux, A. (1988). Social support: theory, research, and intervention. New York: Praeger.

Colvin, M., Cullen, F. T., & Vander Ven, T. (2002). Coercion, social support, and crime: an emerging theoretical consensus. Criminology, 40, 19–42.

Hagan, J., & McCarthy, B. (1997). Mean streets: youth crime and homelessness. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cullen, F. T., & Wright, J. P. (1997). Liberating the anomie-strain paradigm: implications from social support theory. In N. Passas & R. Agnew (Eds.), The future of anomie theory (pp. 187–206). Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38, 300–314.

Clark, C. (1987). Sympathy biography and sympathy margin. American Journal of Sociology, 93, 290–321.

Shott, S. (1979). Emotion and social life: a symbolic interactionist analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 84, 1317–1334.

Rosenberg, M., & McCullough, C. B. (1981). Mattering: inferred significance and mental health among adolescents. Research in Community and Mental Health, 2, 163–182.

Burke, P. J. (2004). Identities and social structure: the 2003 Cooley-Mead Award Address. Social Psychology Quarterly, 67, 5–15.

Sullivan, M. L. (1989). Getting paid: youth crime and work in the inner city. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York: Norton.

Maruna, S. (2001). Making good: how ex-convicts reform and rebuild their lives. Washington: American Psychological Association Books.

Wright, J. P., & Cullen, F. T. (2001). Parental efficacy and delinquent behavior: do control and support matter? Criminology, 39, 677–706.

Ghazarian, S. R., & Roche, K. M. (2010). Social support and low-income, urban mothers: longitudinal associations with adolescent delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1097–1108.

Meadows, S. O. (2007). Evidence of parallel pathways: gender similarity in the impact of social support on adolescent depression and delinquency. Social Forces, 85, 1143–1167.

Scarpa, A., & Haden, S. C. (2006). Community violence victimization and aggressive behavior: the moderating effects of coping and social support. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 502–515.

Koverola, C., Papas, M. A., Pitts, S., Murtaugh, C., Black, M. M., & Dubowitz, H. (2005). Longitudinal investigation of the relationship among maternal victimization, depressive symptoms, social support, and children’s behavior and development. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 1523–1546.

Owen, A. E., Thompson, M. P., Mitchell, M. D., Kennebrew, S. Y., Paranjape, A., Reddick, T. L., Hargrove, G. L., & Kaslow, L. (2008). Perceived social support as a mediator of the link between intimate partner conflict and child adjustment. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 221–230.

Jiang, S., & Winfree, L. T. (2006). Social support, gender, and intimate adjustment to prison life: insight from a national sample. The Prison Journal, 86, 32–55.

Higgins, G. E., & Boyd, R. J. (2008). Low self-control and deviance: examining the moderation of social support from parents. Deviant Behavior, 29, 388–410.

Allen, J. P., Chango, J., Szwedo, D., Schad, M., & Marston, E. (2012). Predictors of susceptibility to peer influence regarding substance use in adolescence. Child Development, 83, 337–350.

Dong, B., & Krohn, M. D. (2016). Escape from violence: what reduces the enduring consequences of adolescent gang affiliation? Journal of Criminal Justice, 47, 41–50.

Frauenglass, S., Routh, D. K., Pantin, H. M., & Mason, C. A. (1997). Family support decreases influence of deviant peers on Hispanic adolescents’ substance use. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 26, 15–23.

Poole, E. D., & Regoli, R. M. (1979). Parental support, delinquent friends, and delinquency: a test of interaction effects. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 70, 188–193.

Stewart, E. A., Simons, R. L., Conger, R. D., & Scaramella, L. V. (2002). Beyond the interactional relationship between delinquency and parenting practices: the contribution of legal sanctions. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 39, 36–59.

Losel, F., & Farrington, D. P. (2012). Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43, S8–S23.

Farrington, D. P. (2011). Families and crime. In J. Q. Wilson & J. Petersilia (Eds.), Crime and public policy (pp. 130–157). New York: Oxford University Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton.

Conger, R. D. (1991). Adolescence and youth: psychological development in a changing world (4th ed.). New York: HarperCollins.

Rindfuss, R. R. (1991). The young adult years: diversity, structural change, and fertility. Demography, 28, 493–512.

Lemert, E. M. (1972). Human deviance, social problems, and social control. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Schur, E. M. (1971). Labeling deviant behavior. New York: Harper & Row.

Davies, S., & Tanner, J. (2003). The long arm of the law: effects of labeling on employment. The Sociological Quarterly, 44, 385–404.

Lanctot, N., Cernkovich, S. A., & Giordano, P. C. (2007). Delinquent behavior, official delinquency and gender: consequences for adulthood functioning and well-being. Criminology, 45, 131–157.

Sweeten, G. (2012). Scaling criminal offending. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 28, 533–557.

Bernburg, J. G., Krohn, M. D., & Rivera, C. J. (2006). Official labeling, criminal embeddedness, and subsequent delinquency: a longitudinal test of labeling theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 43, 67–88.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data: quantitative applications in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Decker, S. H., & Van Winkle, B. (1996). Life in the gang: family, friends and violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vigil, J. D. (1988). Barrio gangs: street life and identity in Southern California. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Cambridge.: Harvard University Press.

Farrall, S. (2004). Social capital and offender reintegration: making probation desistance focused. In S. Maruna & R. Immarigeon (Eds.), After crime and punishment: pathways to offender reintegration (pp. 57–82). Cullompton: Willan.

Western, B. (2002). The impact of incarceration on wage mobility and inequality. American Sociological Review, 67, 526–546.

Acknowledgments

Support for the Rochester Youth Development Study has been provided by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (86-JN-CX-0007), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA020195, R01DA005512), the National Science Foundation (SBR-9123299), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH63386). Work on this project was also aided by grants to the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany from NICHD (P30HD32041) and NSF (SBR-9512290). Official arrest data were provided electronically by the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services.

Points of view, conclusions, and methodological strategies in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the funding agencies or data sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, B., Krohn, M.D. The Protective Effects of Family Support on the Relationship Between Official Intervention and General Delinquency Across the Life Course. J Dev Life Course Criminology 3, 39–61 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-016-0051-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-016-0051-4