Abstract

Within the context of structural bank reforms, ‘ring-fencing’ has come to be used as a catchword for a broader move towards the segregation of commercial and investment banking in the United States and a number of European jurisdictions, with legislation underway for an EU Regulation on structural measures improving the resilience of EU credit institutions. Traditionally, the term has referred to regulatory strategies employed by host-country authorities in cross-border settings, which involve the segregation of local branches and subsidiaries from a multinational banking group. Against this background, the present paper promotes an integrated, functional understanding of ring-fencing in the context of banking regulation and defines some strategic questions for future structural reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See also, discussing a broader range of meanings than those of relevance within the context of the present paper, Schwarcz (2013), at pp 74–81.

See further infra 2.1.

See also, employing a similar terminology, D’Hulster and Ötker-Robe (2014), at p 2 (‘geographical ring-fencing’, ‘territorial approaches’).

See Independent Commission on Banking (2011). And see id. (April 2011) Interim Report, available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20121204124254/http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/icb_interim_report_full_document.pdf.

Infra 2.3.

See N.Y. [Banking] Law § 606(4).

See Cal. [Financial] Code §§ 1810, 1811(g)–(h).

See, for further discussion, Hüpkes (2000), at pp 143–144.

For a vivid illustration of the perceived advantages in the BCCI case, where home-country supervision was considered weak and unreliable, see, e.g., statement by Patrikis (1998).

Starting with the Basel ‘Concordat’ in 1983, the Basel Committee developed the concept and an increasingly complex set of recommendations on conditions for its effective implementation through a series of documents over time. See, e.g., Gruson and Feuring (1991), at pp 45 et seq, and Norton (1995), at pp 122–146 (Europe); Walker (2001), at pp 83–131.

Starting with Second Council Directive 89/646/EEC of 15 December 1989 on the coordination of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to the taking up and pursuit of the business of credit institutions and amending Directive 77/780/EEC, OJ L 386/1. This instrument was substituted by Directive 2000/12/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 March 2000 relating to the taking up and pursuit of the business of credit institutions, OJ L 126/1, which, in turn, was superseded by Directive 2006/48/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2006 relating to the taking up and pursuit of the business of credit institutions (recast), OJ L 177/1. The present regime has been established by Directive 2013/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms (…), OJ L 176/338, and Regulation (EU) No. 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and amending Regulation (EU) No. 648/2012, OJ L 176/1. Under this new framework, the principle of home-country supervision is now stipulated in Art. 49 of Directive 2013/36/EU, while the ‘European Passport’ principle is set out in the provisions of Title V (Arts. 35–43) of that instrument. See generally, e.g., Dragomir (2010), at pp 76–78, 165–181; Gortsos (2012), at pp 238–243; Theissen (2013), at pp 32, 41, 200–203.

First Council Directive 77/780/EEC of 12 December 1977 on the coordination of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to the taking up and pursuit of the business of credit institutions, OJ L 322/30; Second Council Directive, supra n. 15.

Directive 2001/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 April 2001 on the reorganisation and winding up of credit institutions, OJ L 125, p 15.

Council Regulation (EC) No. 1346/2000 of 29 May 2000 on insolvency proceedings OJ L 160/1.

Directive 2001/24/EC, supra n. 18, Arts. 3(1) (on reorganisation measures) and 9(1)(1) (on winding-up).

Ibid., Arts. 3(2) and 9(1)(2), respectively.

Council Regulation (EC) No. 1346/2000 of 29 May 2000 on insolvency proceedings, OJ L 160/1.

Cf. Directive 2001/24/EC, supra n. 18, Preamble, Recital 6.

Ibid., Title IV.

For further discussion, see Binder (2005), at pp 697–711.

See, in particular, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2010).

See Financial Stability Board (2011).

Directive 2014/59/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 establishing a framework for the recovery and resolution of credit institutions and investment firms (…), OJ L 173, at p 190.

Ibid., Titles V (‘Cross-border Group Resolution’ within the EU) and VI (‘Relations with Third Countries’).

See generally ibid., Arts. 87 (general principles), 88 (resolution colleges), 91 and 92 (procedural and substantive requirements for resolution action in relation to groups); specifically on the conditions for independent action by host authorities in this context, see Arts. 91(8) and 92(4).

E.g., remarks by William C Dudley, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, at the Conference ‘Planning for the Orderly Resolution of a Global Systemically Important Bank’, Washington, 18 October 2013, available at http://www.bis.org/review/r131021d.pdf; speech by Jerome H Powell, Member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, at The University Club, New York, 2 July 2013, available at http://www.bis.org/review/r130703b.pdf.

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010).

Cf. Federal Reserve System, Enhanced Prudential Standards for Bank Holding Companies and Foreign Banking Organizations (amending 12 CFR Part 252), Federal Register vol. 79 no. 59, p 17241 (27 March 2014), at pp 17268–17269. The requirement for foreign banking organisations holding US assets of USD 50 bn or more to establish an intermediate holding company is prescribed by §§ 252.150 and 252.153.

See, for further discussion, Binder (2015).

See Financial Stability Board (10 November 2014) Adequacy of Loss-Absorbing Capacity of Global Systemically Important Banks in Resolution. Consultative Document, available at http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/wp-content/uploads/TLAC-Condoc-6-Nov-2014-FINAL.pdf; see also Financial Stability Board (27 October 2014) Structural Banking Reforms. Cross-Border Consistencies and Global Financial Stability Implications. Report to G20 Leaders for the November 2014 Summit, available at http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_141027.pdf, at pp 7–8.

For an early definition that reflects this approach, see Song (2004), at p 19, available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2004/wp0482.pdf. For a comparison of host-country practices, see D’Hulster (2014). And see, discussing both ex ante and ex post ring-fencing, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2010), at p 16.

E.g., N.Y. [Banking] Law § 202-b; Cal. Financial Code § 1810.

See, again, supra n. 38.

Theissen, ibid.

See BRRD, supra n. 30, Arts. 6(6)(2)(c) and 7(2)-(4) (on recovery plans) and 17(5)(g) and (h) and 18 (on powers to address or remove impediments to resolvability). For further discussion, see Binder (2014).

Directive 2013/36/EU, supra n. 15, Arts. 35–43; for further discussion, see supra nn. 14 and 15 and accompanying text.

For details, see Directive 2013/36/EU, supra n. 15, Ch. 3, and Regulation (EU) No. 575/2013, supra n. 15, Ch. 2. See generally, Theissen (2013), at pp 248–258.

On the status of initiatives for the development of a legal framework for the international coordination of group insolvencies, see, e.g., Eidenmüller and Frobenius (2013).

Infra, text accompanying nn. 67 and 68.

See generally Fiechter et al. (2011).

Supra nn. 34 and 35 and accompanying text.

See CRD IV, Arts. 51, 114(1), 116(6), 117(1)(1)(a) and 158.

BRRD, supra n. 30, Art. 17. The provision is embedded in the Directive’s requirements on ‘recovery planning’ by institutions and groups (Arts. 5–9) and ‘resolution planning’ by resolution authorities (Arts. 10–14, see also Art. 15, which requires resolution authorities to carry out an assessment of each institution’s resolvability). For further discussion, see Singh (2015, forthcoming); Binder (2014).

As to which, see infra 2.3.2.2.

Theissen (2013), at p 247.

Ibid.

Cf., e.g., EU-Kommission kritisiert BaFin, Handelsblatt, 3 January 2013, p 32.

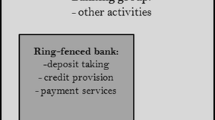

Vickers Report, supra n. 4, at pp 9-11, and, for a detailed discussion, Part I, Ch. 3, pp 35–41.

Ibid., and, for a detailed discussion, Part I, Ch. 3, pp 41–62.

Ibid., and, for a detailed discussion, Part I, Ch. 3, pp 62–76.

Ibid., and, for a detailed discussion, Part I, Ch. 3, p 67.

And see the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Ring-Fenced Bodies and Core Activities) Order 2014, S.I. 2014 No. 1960, and The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Excluded Activities and Prohibitions) Order 2014.

The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Ring-Fenced Bodies and Core Activities) Order 2014, supra n. 62, paras 2(2), 9 and 10: accounts by individuals from EEA countries with less than GBP 250,000 or corporate persons with less than GBP 6.5 m annual turnover.

The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Ring-Fenced Bodies and Core Activities) Order 2014, supra n. 62, paras 11 and 12.

Ibid., at p 155.

Vickers Report, supra n. 4, at pp 63–64.

HM Treasury, Department for Business Innovation and Skills (February 2013) Banking Reform: A New Structure for Stability and Growth, CM 8545, Annex A.1, at p 31, available at http://www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm85/8545/8545.pdf.

Supra n. 34.

See http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/31/opinion/31volcker.html/?pagewanted=all; and see Prohibiting Certain High-Risk Investment Activities by Banks and Bank Holding Companies before the S. Comm. on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, 111th Cong. 2 (February 2, 2010) (testimony of the Honorable Paul Volcker, Chairman, President’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board). This concept was elaborated already by a G-30 committee under the chairmanship of Paul Volcker as early as January 2009, see Group of Thirty, Working Group on Financial Reform (2009) Financial Reform: A Framework for Financial Stability, at p 28, available at http://www.group30.org/rpt_03.shtml. See Manasfi (2013), 196–197.

See Prohibitions and Restrictions on Proprietary Trading and Certain Interests in, and Relationships with, Hedge Funds and Private Equity Funds; Final Rule, Federal Register Vol. 79 No. 21, 31 January 2014, pp 5535–6076. The final version of the rule was prepared on the basis of a report released by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) on 18 January 2011, see FSOC (2011) Study and Recommendations on Prohibitions on Proprietary Trading and Certain Relationships with Hedge Funds and Private Equity Funds, available at http://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/Documents/Volcker%20s%20%20619%20study%20final%201%2018%2011%20rg.pdf.

See 12 USC § 1851(h)(4) (prohibition of proprietary trading) and § 1851(a)(1)(B) (prohibition on acquir[ing] or retain[ing] any equity, partnership, or other ownership interest in or sponsor[ing] a hedge fund or a private equity fund). And see Final Rule, supra n. 73, Subpart B – Proprietary Trading Restrictions. For a brief summary, see Doyle et al. (2010); see also, for an extensive analysis, Whitehead (2011).

Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall Act), Pub. L. No. 73-66, 48 Stat. 162 (1933).

See 12 USC § 1851(a).

12 USC § 1851(h)(1).

12 USC § 1851(h)(4).

See generally, 12 USC § 1851(d) and, for further discussion, Dombalagian (2012), at pp 401–402; FSOC, supra n. 73, at pp 18–25.

12 USC § 1851(d)(1)(B).

See Final Rule, supra n. 73, § 75.4(b) and Appendix A, and explanatory notes, at p 5544; FSOC, supra n. 73, at pp 5, 31–32, 36–43; see also (for a discussion of merits and shortcomings of this approach) Chow and Surti (2011), at pp 20–21.

High-Level Expert Group on Reforming the Structure of the EU Banking Sector (2012) Final Report, available at http://www.ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/high-level_expert_group/report_en.pdf (‘Liikanen Report’).

Ibid., at pp 88–91.

Ibid., at pp 101–103.

European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council on structural measures improving the resilience of EU credit institutions, COM (2014) 43 final. For an introduction (in German), see Lehmann and Rehahn (2014).

Commission Proposal, supra n. 88, Art. 6(1)(a).

Ibid., Art. 6(1)(b). Note that this does not include the extension of guarantees and similar instruments in relation to the funding of such vehicles.

Commission Proposal, supra n. 88, Art. 3(1)(a); for Directive 2013/36/EU, see supra n. 15.

See Commission Proposal, supra n. 88, Art. 3(1)(b), referring to EU credit institutions, parents or branches of third-country credit institutions ‘(…) that for a period of three consecutive years [have] total assets amounting at least to EUR 30 billion and [have] trading activities amounting at least to EUR 70 billion or 10 per cent of [their] total assets …’.

Ibid., at p 8; Preamble, Recital 16. The proposed technical definition of ‘market-making’ is to be found in Art. 5(12), whereas ‘proprietary trading’ is defined in Art. 5(4).

As defined in ibid., Art. 8(1).

For details, see ibid., Art. 9(2).

For details, see ibid., Arts. 10–21.

Ibid., Art. 23.

Ibid., Art. 21(1).

See Banque Nationale de Belgique (June 2012) Rapport intérimaire: Réformes bancaires structurelles en Belgique, available at http://www.bnb.be/doc/ts/Publications/NBBreport/2012/StructureleHervormingen_Fr.pdf.

Banque Nationale de Belgique (July 2013) Réformes bancaires structurelles en Belgique: rapport final, available at http://www.bnb.be/doc/ts/publications/NBBReport/2013/StructuralBankingReformsFR.pdf.

Loi relative au statut et au contrôle des établissements de crédit, 25 April 2014, Moniteur Belge Ed. 2, 7 June 2014, p 36794, Arts. 117 (definitions), 119 (general prohibition), 120–125 (qualifications and exemptions) and 126-127 (transfer to other entities).

See Assemblée nationale, No. 566, Projet de loi de séparation et de régulation des activités bancaires, enregistré à la Présidence de l’Assemblée nationale le 19 décembre 2012. The legislative file, accompanied by a detailed impact assessment, is available at http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/14/dossiers/separation_regulation_activites_bancaires.asp.

Loi no. 2013-672 du 26 juillet 2013 de séparation et de régulation des activités bancaires, Journal Officiel de la République Française no. 0173 du 27 juillet 2013, p 12530. For a short introduction, see Fernandez-Bollo (2013).

Loi no. 2013-672, supra n. 103, Arts. 2 and 5.

Code monétaire et financier, Arts. L511-47 et seq., as introduced by Loi no. 2013-672 (supra n. 103), Art. 2.

Bundesregierung, Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Abschirmung von Risiken und zur Planung der Sanierung und Abwicklung von Kreditinstituten und Finanzgruppen, Bundesrats-Drucksache 94/13 of 8 February 2013.

Gesetz zur Abschirmung von Risiken und zur Planung der Sanierung und Abwicklung von Kreditinstituten und Finanzgruppen, 7 August 2013, Bundesgesetzblatt, Part I, p 3090. For discussion, see, e.g., Brandi and Gieseler (2013), at pp 744–746; Schelo and Steck (2013), at pp 236–244; Möslein (2013).

Gesetz über das Kreditwesen (Kreditwesengesetz), 9 September 1998, Bundesgesetzblatt, Part I, p 2776, [Banking Act], § 3(2) as amended.

Ibid., § 3(4).

Ibid., §§ 3(4), 25f.

Cf., for Belgium, Banque Nationale de Belgique, supra n. 100, at pp 1–2, 7–8; for France, Assemblée nationale, supra n. 102, at pp 10–12; for Germany, Government Bill, supra n. 106, at p 2.

See, pointedly, the French bill, Assemblée nationale, supra n. 102, at p 8 (arguing that the crisis as such did not undermine confidence in the merits of universal banking). And see the in-depth discussion in Banque Nationale de Belgique, supra n. 100, at pp 11–12.

Cf., for Belgium, Loi relative au statut et au contrôle des établissements de crédit, supra n. 101, Art. 121 § 1. For France, cf. Code monétaire et financier, Art. L. 511-47 (as amended by Loi no. 2013-672, supra n. 103). For Germany, cf. Kreditwesengesetz, supra n. 108, § 3(2)(2).

See, for details, Loi relative au statut et au contrôle des établissements de credit (Belgium), supra n. 101, Art. 123 (quantitative thresholds to be determined in delegated legislation); Code monétaire et financier as amended by Loi no. 2013-672 (France), supra n. 103, Art. L. 511-47 al. V; Kreditwesengesetz (Germany), supra n. 108, § 3(4).

See supra, text accompanying n. 52. This context is clearly reflected in the preparatory legislative work in all three jurisdictions, see for Belgium, Banque Nationale de Belgique, supra n. 100, at pp 8, 13–16; for France, see Assemblée nationale, supra n. 102, at pp 19–23; for Germany, Government Bill, supra n. 106, at pp 1–3.

Ibid.

Banque Nationale de Belgique, supra n. 100.

Banque Nationale de Belgique, interim report, supra n. 99, at pp 37–41.

Neither the French nor the German proposals (supra nn. 102 and 106, respectively) disclose relevant empirical data.

See, e.g., the German legislative proposal, supra n. 106, at p 6 (quantifying costs for the creation of new trading entities in the amount of some 19.1 m. euro and unspecified ongoing costs in the amount of 28.7 m. euro); for the UK proposals, see supra, text accompanying n. 70. The French reform bill expressly declares estimations of costs to be impossible for the time being, see Assemblée nationale, supra n. 102, at p 17.

Schwarcz (2013), at p 82 (footnote omitted).

Ibid., at p 88.

See also Testimony by Mr Daniel K Tarullo, Member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, before the Committee on Financial Services, US House of Representatives, Washington DC, 5 February 2014, available at http://www.bis.org/review/r140205b.pdf.

See supra 2.1 and 2.2.

Financial Stability Board, Cross-Border Consistencies, supra n. 37.

On the need for a sound information basis as a precondition for effective regulation, see generally (in the context of corporate law) Binder (2012), at pp 290–293.

For a similar conclusion, see Möslein (2013), at p 369.

For a partly similar list of unresolved issues, see Gambacorta and van Rixtel (2013), at pp 4–5.

In particular, risks from proprietary trading, which have been found particularly difficult to capture.

Regarding which, see supra, text accompanying n. 68.

Supra 2.2.2.

For a similar conclusion, see Schwarcz (2013), at p 96.

For similar considerations, cf. D’Hulster and Ötker-Robe (2014), at pp 10–13.

References

Brunnermeier M et al (2009) The fundamental principles of financial regulation. Geneva Rep World Econ 11

Bainbridge A et al (2014) The banking reform act 2013. Compliance Off Bull 1

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (1992) The insolvency liquidation of a multinational bank. http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs10c.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2010) Report and recommendations of the cross-border bank resolution group. http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs169.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Binder JH (2005) Bankeninsolvenzen im Spannungsfeld zwischen Bankaufsichts- und Insolvenzrecht. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin

Binder JH (2012) Regulierungsinstrumente und Regulierungsstrategien im Kapitalgesellschaftsrecht. Mohr Siebeck, Tuebingen

Binder JH (2014) Resolution planning and structural bank reform within the banking union, SAFE Working Paper No. 81, available at http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2540038

Binder JH (2015) Resolution tools. In: Binder JH, Singh D (eds) Bank recovery and resolution in Europe: the BRRD in context, Chap 3. Oxford University Press, Oxford (forthcoming). http://ssrn.com/abstract=2499613

Brandi TO, Gieseler K (2013) Entwurf des Trennbankengesetzes. Der Betrieb 741

Chambers-Jones C (2011) The Vickers Report. Bus Law Rev 32:280

Chow JTS, Surti J (2011) Making banks safer: can Volcker and Vickers do it? IMF Working Paper WP/11/236. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2011/wp11236.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

D’Hulster K (2014) Ring-fencing cross-border banks: how is it done and how important is it? http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2384905. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

D’Hulster K, Ötker-Robe I (2014) Ring-fencing cross-border banks: an effective supervisory response? http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2384687. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Dombalagian OH (2012) Proprietary trading: of scourges, scapegoats, and scofflaws. Univ Cincinnati Law Rev 81:387

Doyle P et al (2010) New ‘Volcker Rule’ to impose significant restrictions on banking entities, other significant financial service companies. Bank Law J 127:686

Dragomir L (2010) European prudential banking regulation and supervision. Routledge, London

Eidenmüller H, Frobenius T (2013) A new approach to regulating group insolvencies. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2258874. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Fiechter J et al (2011) Subsidiaries or branches: does one size fit all? IMF staff discussion note. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2011/sdn1104.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Fernandez-Bollo E (2013) Structural reform and supervision of the banking sector in France. OECD J Financ Mark Trends. doi:10.1787/fmt-2013-5k41z8t3mrhg. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Financial Stability Board (2011) Key attributes of effective resolution regimes for financial institutions. http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_111104cc.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Gambacorta L, van Rixtel A (2013) Structural bank regulation initiatives: approaches and implications. BIS Working Papers No. 412

Gatto JD (1985) Branches, subsidiaries and foreign bank insolvency. J Comp Cap Mark Law 7:173

Goodhart CAE (2012) The Vickers Report: an assessment. Law Financ Mark Law Rev 6:32

Gortsos C (2012) Fundamentals of public international financial law. Nomos, Baden-Baden

Group of Thirty (1998) International insolvencies in the financial sector. A Study Group report

Gruson M, Feuring W (1991) Convergence of bank prudential supervision standards and practices within the European community. In: Norton JJ (ed) Bank regulation and supervision in the 1990s. Lloyds of London Press, London

Hudson A (2013) Banking regulation and the ring-fence. Compliance Off Bull 1

Hüpkes E (2000) The legal aspects of bank insolvency. Kluwer, The Hague

Independent Commission on Banking (2011) Final report—recommendations (the ‘Vickers Report’). http://www.gov.uk/government/policies/creating-stronger-and-safer-banks. Accessed 20 June 2014

Kotlikoff LJ (2012) The Vickers Commission’s failure. VoxEU. http://www.voxeu.org/article/vickers-commission-s-failure. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Lastra RM (2011) International law principles applicable to cross-border bank insolvency. In: Lastra RM (ed) Cross-border insolvency. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 161

Lehmann M, Rehahn J (2014) Trennbanken nach Brüsseler Art: Der Kommissionsvorschlag vor dem Hintergrund nationaler Modelle. WM Wertpapiermitteilungen – Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Bankrecht 68:1793

Manasfi JAD (2013) Systemic risk and Dodd-Frank’s Volcker Rule. William Mary Bus Law Rev 4:181

Möslein F (2013a) Grundsatz- und Anwendungsfragen zur Spartentrennung nach dem sog. Trennbankengesetz, BKR Zeitschrift für Bank- und Kapitalmarktrecht 397

Möslein F (2013b) Die Trennung von Wertpapier- und sonstigem Bankgeschäft: Trennbankensystem, Ring-fencing und Volcker-Rule als Mittel zur Eindämmung systemischer Gefahren für das Finanzsystem. ORDO Jahrbuch für die Ordnung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft 64:349

Moss G, Wessels B (eds) (2006) EU banking and insurance insolvency. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Norton JJ (1995) Devising international bank supervisory standards. Graham & Trotman, London

Patrikis ET (1998) First Vice President, Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In: Group of Thirty (1998) International insolvencies in the financial sector. A Study Group Report, p 87

Patrikis ET (1999) Role and functions of authorities: supervision, insolvency preventive and liquidation. In: Giovanoli M, Heinrich G (eds) International bank insolvencies: a central bank perspective. Kluwer, The Hague

Peters G (2011) Developments in the EU. In: Lastra RM (ed) Cross-border bank insolvency. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 128–160

Piasio CA (2013) It’s complicated: why the Volcker Rule is unworkable. Seton Hall Law Rev 43:737

Quinn B, Morgenthau RM, Lord Bingham T (2000) Banking supervision after BCCI. In: Goodhart CAE (ed) The emerging framework of financial regulation. Central Banking Publications, London, p 445

Schelo S, Steck A (2013) Das Trennbankengesetz: Prävention durch Bankentestamente und Risikoabschirmung. ZBB Zeitschrift für Bankrecht und Bankbetrieb 227

Schwarcz SL (2013) Ring-fencing. South Calif Law Rev 87:69

Singh D (2015) Crisis prevention. In: Binder JH, Singh D (eds) Bank recovery and resolution in Europe: the BRRD in context, Chap 2. Oxford University Press, Oxford (forthcoming)

Song I (2004) Foreign bank supervision and challenges to emerging market supervisors. IMF Working Paper WP/04/82

Staikouras PK (2011) Universal banks, universal crises? Disentangling myths from realities in quest of a new regulatory and supervisory landscape. JCLS 11:139

Theissen R (2013) EU banking supervision. Eleven International, The Hague

Tröger TH (2013) Effective supervision of transnational financial institutions. Tex Int Law J 48:177

Walker GA (2001) International banking regulation—law, policy and practice. Kluwer, The Hague

Whitehead CK (2011) The Volcker Rule and evolving financial markets. Harv Bus Law Rev 1:39

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Binder, JH. Ring-Fencing: An Integrated Approach with Many Unknowns. Eur Bus Org Law Rev 16, 97–119 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-015-0005-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-015-0005-z