Abstract

Pelvic fractures can lead to life-threatening hemorrhage, particularly as they tend to occur in the setting of polytrauma. Several approaches to hemorrhage control have been employed in pelvic fracture patients over the years. This review describes the indications, operative technique, and outcomes for preperitoneal pelvic packing (PPP). Pelvic packing should be considered for every hemodynamically unstable patient with a significant pelvic fracture. We describe how this can be accomplished in coordination with other resuscitative efforts and operative needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pelvic ring fractures are a common cause of morbidity and mortality in trauma, occurring in close to 10 % of blunt trauma patients [1]. The severity of injury in patients with pelvic fractures ranges from minor trauma to debilitating morbidity and mortality. In fact, over 10 % of these patients may die before reaching the hospital [2, 3]. These patients are more commonly men (60 %), with injury peaks in the young adult period (ages 15–30 years) and in elder adults (>55 years). The older patient population tends to have a worse outcome despite relatively stable pelvic fracture patterns [1, 2, 4]. A subset of 8–10 % of patients with pelvic fractures require blood transfusions [5, 6••]. These are the severely injured subpopulation of pelvic fracture patients that have mortality rates of over 30–40 % in modern series [7–9].

This review focuses on this subset of pelvic fracture patients who are hemodynamically unstable. These patients may have associated extrapelvic injuries (traumatic brain injury, thoracoabdominal, or extremity trauma) or injuries to structures within the pelvis (bladder, rectum, vasculature). Early identification of these associated injuries can alter one’s operative timing and technique and therefore a high index of suspicion for the associated injuries is mandatory. A crucial point in the decision-making process, however, is identifying the pelvis as a possible site of post-traumatic bleeding. With one third of pelvic fracture-related mortality due to uncontrolled hemorrhage [10–12], early identification of this potential source during the evaluation is paramount. This permits institution of damage control resuscitation and operative techniques, if needed, to prevent early exsanguination and the lethal triad of hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis that can follow hemorrhage.

There are several commonly used classification systems for pelvic fractures. We prefer to use the Young and Burgess classification system, which classifies injuries by mechanism—vertical shear in the presence of vertical displacement, anterior-posterior compression with significant pubic symphyseal diastasis (APC I, II, III depending on degree of sacroiliac dislocation) or lateral compression fractures (LC I, II, III depending on disruption of contralateral elements and/or iliac wing fracture) [13, 14]. There have been several retrospective studies that have shown an association between pelvic fracture classification and risk of arterial injury and/or the need for transfusions [15•, 16]. However, while these classifications do not consistently correlate with the need for pelvic angiography [17], they tend to correlate with the need for fixation. Higher grade, “unstable” injuries (VS, APC II and III, and LC II and III) are more likely to require operative intervention.

Pelvic packing was originally described 20 years ago in the European literature [18–23]. It was recognized that the vast majority of pelvic bleeding originates from the presacral venous plexus and fracture sites—sources that will stop with tamponade—while only 10–20 % is related to major arterial injury [1, 2, 24•, 25]. The emphasis on early control of hemorrhage via packing to facilitate resuscitation, assessment, and treatment of associated injuries was embraced in European centers. They reported excellent results with effective control of hemorrhage [20, 23, 26]. By using a modified technique [24•], using a preperitoneal approach, rather than transabdominal pelvic packing, we reported decreased transfusion requirements and decreased mortality in this seriously injured patient cohort [6••].

Initial Evaluation and Management of the Pelvic Fracture Patient

In the hemodynamically unstable patient, rapid assessment for potential sources of hemorrhage is performed. Simple measures, including physical examination, chest and pelvis radiographs, and ultrasound of the abdomen, in the trauma bay should delineate the potential sources. As soon as a pelvic fracture is suspected in a hemodynamically unstable patient, several measures should be instituted while determining the need for hemorrhage control. These include (1) rapid stabilization of the pelvis, (2) institution of massive transfusion protocols, and (3) identification of injuries directly related to the pelvic fracture.

Stabilization of the pelvis in the trauma bay can be accomplished with a pelvic binder, wrapping of the pelvis with a sheet, or use of an orthopedic C-clamp [20, 27–31]. Although open book fractures may be reduced, patients with significant disruption of the posterior elements may have further distraction of their fractures with anterior element closure. Minimizing compressive stabilization will limit the risk of pressure sores and nerve injuries that have been reported with such devices. More definitive yet expeditious stabilization with external fixation of the pelvic fracture can be performed in the operating room [5, 21, 30, 32–34]. Concurrent resuscitation of the patient during fracture stabilization is critical. Each institution should develop and implement their own massive transfusion protocol for critically ill and injured patients. Triggering the protocol early in the assessment of the unstable patient permits early delivery of appropriate blood products.

Pelvic fractures are associated with many other types of injuries; it is critical to consider other indicated procedures when proceeding to the operating room for a serious pelvis fracture—exploratory laparotomy based on a positive focused abdominal sonogram for trauma (FAST) exam, thoracotomy based on concern for intrathoracic injury, neurosurgical procedure when there is concern for significant brain injury. Specific to pelvic trauma is the evaluation for associated injuries to the genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and gynecologic systems. Recognition and identification of these injuries permits appropriate concurrent intraoperative management and postoperative care. Concern for a urethral or bladder injury is based upon blood evident at the meatus, gross hematuria, or inability to pass a Foley catheter. Rectal injury may manifest as blood on rectal examination; similarly, a vaginal injury may be identified by blood evident at the introitus or on speculum examination. Any such findings alter the management plan and may result in the classification of the injury as an open pelvic fracture.

Indications for Preperitoneal Pelvic Packing

In the unstable patient with a pelvic fracture, initial assessment should identify the primary etiology of hemorrhage. If the pelvic fracture is considered the likely source, based upon examination and imaging in the trauma bay, one must then determine the significance of the bleeding. As noted previously, only 10 % of all pelvic fracture patients require transfusion therapy. If hemodynamically stable, the patient can undergo appropriate CT imaging for delineation of the pelvic fracture geometry and other traumatic injuries. It is the small subset of patients who remain hemodynamically unstable in whom pelvic fracture-related hemorrhage must be urgently addressed. Two options exist to address fracture related hemorrhage: angioembolization or preperitoneal pelvic packing (PPP). Historically, all patients underwent angioembolization for control of significant pelvic fracture-related hemorrhage. However, with the reinvention of PPP in the USA, a second option is available. Our algorithm for the institution of PPP is presented in Fig. 1. If a pelvic fracture patient requires at least 2 units of packed red blood cells and remains hypotensive, we proceed to the operating room for PPP. The current “trigger” for performing PPP is the same “trigger” we historically used for angioembolization. So our intervention point is identical, but our choice of technique for controlling hemorrhage has changed. We opt to directly address the presumed source of pelvic fracture bleeding, the bony and venous sources, with packing of the pelvic space.

The decision process delineated above, and presented in Fig. 1, is typical for the majority of pelvic fracture patients who are unstable. These patients rarely stabilize enough for a trip to the CT scanner, often declaring themselves early in their course in the emergency department. Occasionally, an unstable patient is taken to the operating room for laparotomy without recognition of their pelvic fracture. In this scenario, if a significant pelvic hematoma is identified in a patient who remains hypotensive after addressing abdominal sources of hemorrhage, PPP should be considered.

Operative Considerations

When proceeding to the operating room (OR), anticipation of needed clinicians, instruments, and equipment promotes operative efficiency at a time where minutes matter. Standardized protocols for the management of injured patients incorporating a multidisciplinary approach have been documented to streamline care and speed the time to definitive hemorrhage control [35, 36, 37•, 38, 39].

The orthopedic team should already be involved with the patient during initial evaluation in the trauma bay as they are integral to the decision for operative intervention. They can directly communicate with the OR prep team what instruments are needed for external fixation of the pelvis. Likewise, the urology team should be notified of examination findings concerning for injury and potential need for intraoperative consultation and imaging; if a Foley catheter was not able to be placed in the trauma bay, a suprapubic tube may be necessary until a urethral injury can be evaluated. Items that should be ready upon arrival into the OR include an OR table compatible with fluoroscopy; intraoperative fluoroscopy may be used by the orthopedic team to determine pelvic alignment or pin placement, by the urology team for on-table cystogram, or by the trauma surgeon to perform lower extremity on-table angiography. The OR nursing staff should be alerted to the potential need for multiple surgeons operating simultaneously; each surgical team may need their own set of instruments to provide concurrent care. Coordination of the orthopedic and trauma teams, with input from the urology and neurosurgery teams as indicated, enables delineation of operative tasks. For example, in a patient requiring thoracotomy or laparotomy, the trauma team should proceed with this operation while the orthopedic team packs the pelvis. Alternatively, if there are multiple lower extremity fractures particularly with associated compartment syndromes, the orthopedic team should focus on extremity fixation and decompression while the trauma team performs PPP. Finally, equipment necessary for a rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy or vaginal examination should be available; these procedures are expeditiously done at the end of the case after hemorrhage is controlled. Such measures are only diagnostic as definitive management of a rectal injury with diversion can be delayed. Classification of the fracture as an open fracture, however, alters antibiotic therapy in the immediate postoperative period.

Technique of Preperitoneal Pelvic Packing

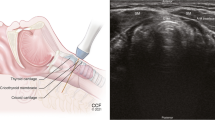

The patient is prepped in the usual fashion for trauma, from the neck to the knees, taking care to prep widely at the level of the pelvis for probable placement of an external fixator. Ideally, external fixation of the pelvis is performed first. For PPP, a vertical midline incision is made from the pubic symphysis extending up 6–8 cm (Fig. 2) [24•]. If a laparotomy is necessary, the two incisions should remain separate or effective tamponade of the pelvic space will be difficult. The laparotomy incision may extend from the xiphoid to just below the umbilicus while the PPP incision is approximately 6 cm away in the suprapubic area.

The PPP incision is carried through skin and subcutaneous tissue to fascia, which is incised in the midline. Once the preperitoneal space is entered, blood from the hematoma egresses. The hematoma often dissects the planes of the pelvic space; in reality, the pelvic space is an inverted U shape extending around the bladder which is comprised of the preperitoneal, paravesical, and presacral space. To place the packs, the bladder is retracted to the contralateral side to allow introduction of three standard surgical laparotomy pads (Fig. 3). Due to the amount of blood in the pelvic space, actual visualization of the space is not possible; rather, rapid packing into the pool of blood is performed. A blunt instrument such as a Cobb elevator or ringed forceps is used to push the first laparotomy pad all the way down onto the sacrum. Typically six pads complete the packing, but up to nine pads may be necessary to complete the tamponade.

If a bladder injury is identified, it should be repaired primarily. Placement of suprapubic tubes should be done through a separate stab incision rather than bringing the Foley through the midline fascial closure. The fascia is then closed using a running absorbable monofilament (such as a 0-polydiaxanone) and the skin is closed with staples (Fig. 4).

Following completion of any other operative procedures, the patient is taken to the SICU for further resuscitation and eventual CT scan imaging. If the patient remains hemodynamically unstable after packing despite ongoing transfusion, other sources of hemorrhage or etiologies of shock should be entertained (thoracic or abdominal sources, extremity losses, cardiogenic shock, neurogenic shock). In approximately 15 % of patients undergoing PPP, angioembolization is used to address arterial bleeding [6••]. Indications for diagnostic angiography following PPP are over 4 units of blood in the 12 h following the operating room once coagulopathy has been corrected. Following resuscitation and stabilization, pelvic packing is removed 24–48 h later once the patient’s coagulopathy is resolved.

Experience

Because of the variable use of PPP, there are few large studies evaluating outcomes [40]. The most recent evaluation for a single institution’s experience with PPP reported a mortality rate of 21 % [6]; this is a markedly lower mortality rate compared to modern series [8, 9, 41–44]. PPP will quell ongoing bleeding to allow adequate time for any necessary angiography/embolization, or assessment and treatment of associated injuries. Once the pelvis is packed, bleeding is slowed and patients may stabilize enough to further evaluate with head or other CT scans or to address other injured organ systems. It will also give time to correct coagulopathy and adequately resuscitate the patient in the intensive care unit. The time window afforded by PPP is an average of 10 h in those patients who required angioembolization subsequent to pelvic packing [6••]. This time window is particularly advantageous in institutions where angiography is not immediately available or the patient must be transported to another facility for angiography.

The complication of pelvic infection has not been eradicated, especially in the presence of associated pelvic organ injury (bowel and bladder) or open fracture, reaching close to 15 % in the most recent study [6••]. Timing of pack removal should be done to prevent repacking as infection rates of the pelvic space were significantly higher in those patients undergoing repeat PPP (6 vs 47 %) [6••]. Ideally, packs are removed by 48 h; however, physiologic restoration and correction of coagulopathy are critical before returning to the OR.

The role of angiography/embolization in the context of pelvic hemorrhage is important to consider. There are some who advocate angiography first, even in the setting of hemodynamic instability [45, 46••]. Studies that have been done of angiography/embolization are difficult to directly compare with PPP because indications for intervention for pelvic fracture related hemorrhage or angiography vary from institution to institution; for example, some institutions send every unstable patient with a pelvic fracture directly to angiography, while some patients are excluded with a positive FAST; other institutions only send patients with a positive blush on CT scan, a large pelvic hematoma, or persistent hypotension [8, 9, 15•, 28, 37•, 45, 47•, 48, 49]. It has been recognized that a blush on CT scan is not a specific indicator of need for angioembolization [11]. While there is a role for angioembolization, there are potential deterrents to using this as a first-line treatment. Angiography may be a time-consuming procedure in a hemodynamically unstable patient, and resuscitation of the critically injured patient in the interventional radiology suite may be limited. Moreover, the patient may have other injuries that require urgent operative intervention—a bleeding spleen, an expanding subdural, a compartment syndrome, a threatened limb, or caked hemothorax to name just a few. Relegating the multiply injured patient to a trip to the IR suite may not be optimal care.

It is important to recognize, however, that PPP is not a stand-alone procedure. Although it appears to effectively halt bony and venous bleeding, there are still patients with arterial hemorrhage that benefit from angioembolization [6••]. Our practice is to proceed to angiography if there is a transfusion requirement of >4 units in 12 h once coagulopathy has been corrected. It is important to recognize, however, that only a diagnostic angiography should be performed. Empiric embolization of the internal iliac arteries is not necessarily warranted in these patients. Without documented arterial extravasation, wanton embolization should be cautioned. The concern for pelvic ischemia after embolization is a recognized complication that should not be ignored.

Next Steps

Management of patients with unstable pelvic fractures remains controversial, and there is no clear standard for hemorrhage control. Will there ever be a randomized study to evaluate the use of angioembolization versus pelvic packing? Does the role of angiography depend on its availability? Is there a universally agreed upon indication for pelvic fracture related hemorrhage intervention? Gansslen et al. have cited indicators for significant hemorrhage including elevated base deficit, and low hemoglobin or temperature that guide their use of PPP and angioembolization [28]. Other authors use these markers, base deficit in particular, to guide need for angiography in the setting of pelvic hemorrhage [50]. No strict criteria exist to identify patients at highest risk for significant arterial injury who may benefit from initial angioembolization. At this point, criteria such as ISS >25, Pelvic AIS ≥4, or findings on CT scan such as blush or large pelvic hematoma may predict arterial bleeding. However, these criteria are often unknown on presentation. Conversely, there are risks associated with PPP, especially infection. With the emergence of new techniques, such as resuscitative endovascular aortic balloon occlusion (REBOA), we may soon have another tool to use in the setting of massive pelvic hemorrhage [51, 52].

Conclusions

We continually strive to improve our management of injured patients. PPP is a powerful tool to include in our armamentarium when faced with a patient with an unstable pelvic fracture. This approach directly addresses the primary source of bleeding from pelvic fractures. Any necessary operative procedures such as laparotomy, thoracotomy, fasciotomy, and stabilization of extremity fractures can occur concurrently; this permits comprehensive care for the multiply injured patient. For those with ongoing bleeding, angioembolization can be used as a complementary procedure following PPP. Ongoing systematic evaluation of patients will further define the roles of PPP, angioembolization, and REBOA; currently, the practicing clinician should be familiar with the strengths and weaknesses of each modality and employ those best suited to the patient and their institution.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Toutouzas K, Alo K, Velmahos G, Chan L. Pelvic fractures: epidemiology and predictors of associated abdominal injuries and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:1–10.

Balogh Z, King KL, Mackay P, McDougall D, Mackenzie S, Evans JA, et al. The epidemiology of pelvic ring fractures: a population-based study. J Trauma. 2007;63:1066–73. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181589fa4.

Papadopoulos IN, Kanakaris N, Bonovas S, Triantafillidis A, Garnavos C, Voros D, et al. Auditing 655 fatalities with pelvic fractures by autopsy as a basis to evaluate trauma care. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:30–43. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.03.017.

Gansslen A, Pohlemann T, Paul C, Lobenhoffer P, Tscherne H. Epidemiology of pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 1996;27 Suppl 1:S–A13–20.

Stahel PF, Mauffrey C, Smith WR, McKean J, Hao J, Burlew CC, et al. External fixation for acute pelvic ring injuries: decision making and technical options. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:882–7. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182a9005f.

Burlew CC, Moore EE, Smith WR, Johnson JL, Biffl WL, Barnett CC, Stahel PF. Preperitoneal pelvic packing/external fixation with secondary angioembolization: optimal care for life-threatening hemorrhage from unstable pelvic fractures. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:628–35. discussion 635–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.020. This article is the largest single-institution modern analysis of preperitoneal pelvic packing. The technique is described and illustrated. Patients undergoing PPP demonstrated a decreased need for transfusions and lower mortality rate. The authors advocate using PPP as the first line therapy for hemodynamically unstable patient due to pelvic fracture-related hemorrhage. PPP can also temporize arterial hemorrhage when angiography is not immediately available.

Tai DKC, Li W-H, Lee K-Y, Cheng M, Lee K-B, Tang L-F, et al. Retroperitoneal pelvic packing in the management of hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures: a level I trauma center experience. J Trauma. 2011;71:E79–86. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31820cede0.

Hou Z, Smith WR, Strohecker KA, Bowen TR, Irgit K, Baro SM, et al. Hemodynamically unstable pelvic fracture management by advanced trauma life support guidelines results in high mortality. Orthopedics. 2012;35:e319–24. doi:10.3928/01477447-20120222-29.

Thorson CM, Ryan ML, Otero CA, Vu T, Borja MJ, Jose J, et al. Operating room or angiography suite for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:364–70. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318243da10. discussion 371–2.

Hauschild O, Aghayev E, von Heyden J, Strohm PC, Culemann U, Pohlemann T, et al. Angioembolization for pelvic hemorrhage control: results from the German pelvic injury register. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:679–84. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318253b5ba.

Verbeek DOF, Zijlstra IAJ, van der Leij C, Ponsen KJ, van Delden OM, Goslings JC. Management of pelvic ring fracture patients with a pelvic “blush” on early computed tomography. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:374–9. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000000094.

Scalea TM, Stein DM, O’Toole RV. Pelvic Fractures. In: Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, Moore EE, editors. Trauma. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

Young JW, Burgess AR, Brumback RJ, Poka A. Pelvic fractures: value of plain radiography in early assessment and management. Acad Radiol. 1986;160:445–51.

Burgess AR, Eastridge BJ, Young JW, Ellison TS, Ellison PS, Poka A, et al. Pelvic ring disruptions: effective classification system and treatment protocols. J Trauma. 1990;30:848–56.

Brun J, Guillot S, Bouzat P, Broux C, Thony F, Genty C, et al. Detecting active pelvic arterial haemorrhage on admission following serious pelvic fracture in multiple trauma patients. Injury. 2014;45:101–6. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2013.06.011. Brun et al. emphasize the importance of utilizing an algorithm to assess patients with hemodynamic instability and pelvic fractures.

Osterhoff G, Scheyerer MJ, Fritz Y, Bouaicha S, Wanner GA, Simmen H-P, et al. Comparing the predictive value of the pelvic ring injury classification systems by Tile and by Young and Burgess. Injury. 2014;45:742–7. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2013.12.003.

Cullinane DC, Schiller HJ, Zielinski MD, Bilaniuk JW, Collier BR, Como J, et al. Eastern association for the surgery of trauma practice management guidelines for hemorrhage in pelvic fracture—update and systematic review. J Trauma. 2011;71:1850–68. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31823dca9a.

Pohlemann T, Gansslen T, Bosch A, Tscherne U. The technique of packing for control of hemorrhage in complex pelvic fractures. Tech Orthop. 1994;9:267–70.

Pohlemann T, Tscherne H, Baumgärtel F, Egbers HJ, Euler E, Maurer F, et al. Pelvic fractures: epidemiology, therapy and long-term outcome. Overview of the multicenter study of the Pelvis Study Group. Unfallchirurg. 1996;99:160–7.

Ertel W, Keel M, Eid K, Platz A, Trentz O. Control of severe hemorrhage using C-clamp and pelvic packing in multiply injured patients with pelvic ring disruption. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:468–74.

Giannoudis PV, Pape HC. Damage control orthopaedics in unstable pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 2004;35:671–7. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2004.03.003.

Totterman A, Madsen JE, Skaga NO, Roise O. Extraperitoneal pelvic packing: a salvage procedure to control massive traumatic pelvic hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2007;62:843–52. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000221673.98117.c9.

van Veen IH, van Leeuwen AA, van Popta T, van Luyt PA, Bode PJ, van Vugt AB. Unstable pelvic fractures: a retrospective analysis. Injury. 1995;26:81–5.

Huittinen VM, Slätis P. Postmortem angiography and dissection of the hypogastric artery in pelvic fractures. Surgery. 1973;73:454–62. This is the classic paper describing the etiology of pelvic fracture-related hemorrhage.

Gänsslen A, Giannoudis P, Pape H-C. Hemorrhage in pelvic fracture: who needs angiography? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2003;9:515–23.

Pohlemann T, Bosch U, Gansslen A, Tscherne H. The Hannover experience in management of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;69–80.

Nunn T, Cosker TDA, Bose D, Pallister I. Immediate application of improvised pelvic binder as first step in extended resuscitation from life-threatening hypovolaemic shock in conscious patients with unstable pelvic injuries. Injury. 2007;38:125–8. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2006.06.026.

Gansslen A, Hildebrand F, Pohlemann T. Management of hemodynamic unstable patients “in extremis” with pelvic ring fractures. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2012;79:193–202.

Heini PF, Witt J, Ganz R. The pelvic C-clamp for the emergency treatment of unstable pelvic ring injuries. A report on clinical experience of 30 cases. Injury. 1996;27 Suppl 1:S–A38–45.

Pizanis A, Pohlemann T, Burkhardt M, Aghayev E, Holstein JH. Emergency stabilization of the pelvic ring: clinical comparison between three different techniques. Injury. 2013;44:1760–4. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2013.07.009.

Chesser TJS, Cross AM, Ward AJ. The use of pelvic binders in the emergent management of potential pelvic trauma. Injury. 2012;43:667–9. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2012.04.003.

Pape H-C. Effects of changing strategies of fracture fixation on immunologic changes and systemic complications after multiple trauma: damage control orthopedic surgery. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1478–84. doi:10.1002/jor.20697.

Pape H-C, Giannoudis P, Krettek C. The timing of fracture treatment in polytrauma patients: relevance of damage control orthopedic surgery. Am J Surg. 2002;183:622–9.

Roberts CS, Pape H-C, Jones AL, Malkani AL, Rodriguez JL, Giannoudis PV. Damage control orthopaedics: evolving concepts in the treatment of patients who have sustained orthopaedic trauma. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:447–62.

Manzini N, Madiba TE. The management of retroperitoneal haematoma discovered at laparotomy for trauma. Injury. 2014;45:1378–83. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2014.01.026.

Perkins ZB, Maytham GD, Koers L, Bates P, Brohi K, Tai NRM. Impact on outcome of a targeted performance improvement programme in haemodynamically unstable patients with a pelvic fracture. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:1090–7. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.96B8.33383.

Tosounidis TI, Giannoudis PV. Pelvic fractures presenting with haemodynamic instability: treatment options and outcomes. Surgeon. 2013;11:344–51. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2013.07.004. The authors describe the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to controlling pelvic hemorrhage.

Biffl WL, Smith WR, Moore EE, Gonzalez RJ, Morgan SJ, Hennessey T, et al. Evolution of a multidisciplinary clinical pathway for the management of unstable patients with pelvic fractures. Ann Surg. 2001;233:843–50.

Mauffrey C, Cuellar III DO, Pieracci F, Hak DJ, Hammerberg EM, Stahel PF, et al. Strategies for the management of haemorrhage following pelvic fractures and associated trauma-induced coagulopathy. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:1143–54. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.96B9.33914.

Metcalfe AJ, Davies K, Ramesh B, O’Kelly A, Rajagopal R. Haemorrhage control in pelvic fractures–a survey of surgical capabilities. Injury. 2011;42:1008–11. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.062.

Heetveld MJ, Harris I, Balogh Z, Schlaphoff G, D’Amours SK, Sugrue M. Hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures: recent care and new guidelines. World J Surg. 2004;28:904–9.

Sathy AK, Starr AJ, Smith WR, et al. The effect of pelvic fracture on mortality after trauma: an analysis of 63,000 trauma patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2803–10.

Hauschild O, Strohm PC, Culemann U, et al. Mortality in patients with pelvic fractures: results from the German pelvic injury register. J Trauma. 2008;64:449–55.

Verbeek D, Sugrue M, Balogh Z, et al. Acute management of hemodynamically unstable pelvic trauma patients: time for a change? Multicenter review of recent practice. World J Surg. 2008;32:1874–82.

Abrassart S, Stern R, Peter R. Unstable pelvic ring injury with hemodynamic instability: what seems the best procedure choice and sequence in the initial management? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99:175–82. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2012.12.014.

Cheng M, Cheung MT, Lee KY, Lee KB, Chan SCH, Wu ACY, et al. Improvement in institutional protocols leads to decreased mortality in patients with haemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. Emerg Med J. 2013. doi:10.1136/emermed-2012-202009. Cheng et al. reviewed the outcomes of severe pelvic fractures over the course of three different protocols (pre-angiography, angiography, pelvic packing) in a single hospital. They demonstrate a reduction in mortality with successive implementation of each protocol: 64% pre-angiography, 42% angiography, and 31% pelvic packing.

Fu C-Y, Wang Y-C, Wu S-C, Chen R-J, Hsieh C-H, Huang H-C, et al. Angioembolization provides benefits in patients with concomitant unstable pelvic fracture and unstable hemodynamics. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:207–13. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2010.11.005. Fu et al. demonstrate a role for angioembolization in patients with hemodynamic instability and pelvic fractures.

El-Haj M, Bloom A, Mosheiff R, Liebergall M, Weil YA. Outcome of angiographic embolization for unstable pelvic ring injuries: factors predicting success. Injury. 2013;44:1750–5. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2013.05.017.

Lindahl J, Handolin L, Söderlund T, Porras M, Hirvensalo E. Angiographic embolization in the treatment of arterial pelvic hemorrhage: evaluation of prognostic mortality-related factors. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2013;39:57–63. doi:10.1007/s00068-012-0242-6.

Toth L, King KL, McGrath B, Balogh ZJ. Factors associated with pelvic fracture-related arterial bleeding during trauma resuscitation. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;1:doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000056.

Morrison JJ, Percival TJ, Markov NP, Villamaria C, Scott DJ, Saches KA, et al. Aortic balloon occlusion is effective in controlling pelvic hemorrhage. J Surg Res. 2012;177:341–7. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2012.04.035.

Scott DJ, Eliason JL, Villamaria C, Morrison JJ, Houston IV R, Spencer JR, et al. A novel fluoroscopy-free, resuscitative endovascular aortic balloon occlusion system in a model of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:122–8. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182946746.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Nina Glass and Clay Cothren Burlew declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Trauma to the Pelvis

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Glass, N.E., Burlew, C.C. Preperitoneal Pelvic Packing: How and When. Curr Trauma Rep 1, 1–7 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-014-0001-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-014-0001-8