Abstract

A flipped classroom, an approach abandoning traditional lectures and having students come together to apply acquired knowledge, requires students to come to class well prepared. The nature of this preparation is currently being debated. Watching web lectures as a preparation has typically been recommended, but more recently, a variety of study materials has been considered to serve students personal learning preferences. The aim of this study was to explore in two flipped courses which online study materials stimulate students most to prepare for in-class activities, to find out whether students differ in their use of study materials, and to explore how students use of online study materials relates to their learning strategies. In a basic science and a clinical course, medical students were provided with web lectures, text selections, scientific papers, books, and formative test questions or case studies. Use of these online materials was determined with questionnaires. All students watched web lectures and read text selections to prepare for in-class activities, but students differed in the extent to which they used more challenging materials. Additionally, the use of online study materials was related to students’ learning strategies that involved regulation and monitoring of study effort. Our findings suggest that students have similar learning preferences as they all use the same “basic materials” to prepare for in-class activities. We interpret the preferential use of web lectures and text selections as being regarded as sufficient for active in-class participation. The less intensive use of other study materials may reflect students’ perception of limited study time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

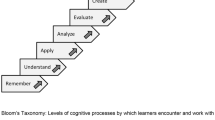

Flipped classrooms are characterized by substantial pre-class preparation, while in-class time is focused on active student-centered learning activities [1–6]. In a flipped or “inverted” classroom approach, students’ pre-class preparation is intended to acquire knowledge and understanding for which a surface approach to learning, such as organizing and rehearsing [7], is sufficient. This acquired knowledge can then be applied during in-class time that is aimed at deep learning activities such as critical thinking and elaboration.

Even though a flipped classroom is a relatively new approach to education, recent publications start supporting its effectiveness. Some studies provide evidence showing improved performance for students learning in the flipped classroom compared to traditional (lecture based) classrooms [5, 8–10], and others indicate that students are more satisfied [11–13]. Conversely, increased time commitments and study load for students have been addressed [1, 8, 14].

As mentioned above, a prerequisite for successful flipped classrooms is that students have “a prepared mind” when coming to class [14–17]. Without sufficient pre-class preparation, knowledge cannot be applied in in-class activities such as analyzing data, solving problems, or participating in in-class patient presentations [18, 19].

The design of pre-class (and in-class) activities is currently being debated. Initial descriptions of flipped classrooms describe how students are provided with web lectures, either newly recorded videos by the teacher or recommended lectures from the internet, to learn new principles in their own time [14]. However, students have access not only to web lectures but often also to textbooks (online) and/or e-learning modules to facilitate pre-class preparation [1, 5, 6, 14, 20]. A variety of study materials has been considered to serve students personal learning preferences [6, 8, 21]. It is of interest to know whether providing web lectures as pre-class preparation would be sufficient for students in a flipped classroom to prepare for in-class activities or that additional materials are required.

This study aimed to explore to what extent students indeed use a variety of suggested online study materials to prepare for in-class activities in two flipped courses, a basic science course and a clinical course. We also aimed to explore whether students differ in their use of online study material. Finally, we aimed to understand how students use different study materials by exploring the relation between the use of materials and self-reported learning strategies. For this study, we operationally defined the flipped classroom model as education in which content information on a factual level is processed outside the classroom, while elaboration and discussion of the materials is organized in a subsequent classroom meeting. Knowing what study materials students use will provide insight in what activities students find most relevant to spend their time on, and knowing what materials they use less might give an indication of what materials can lead to study burden. In addition, knowing what study materials students use most could help teachers in prioritizing what materials they design for their students in situations of limited available time. On the other hand, knowing what materials are related to deeper learning activities might support teachers in deciding on what materials are suitable for preparation and what materials are suitable for in-class activities.

Method

Educational Setting

This study was conducted in two flipped classroom courses of one cohort of the graduate entry 4-year undergraduate medical program at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. In this program, class size is 40. The first course was a 4-week basic science Anatomy course, delivered in the first year of the program (October 2013), and the second course was a 5-week clinical Rheumatology and Orthopedics course taught during the second year (November 2014). Both courses aimed for knowledge acquisition and conceptual understanding.

Pre-class and In-class Activities

In the Anatomy course, all pre-class study materials were presented in a custom made iBook and consisted of text selections on the topic (i.e., descriptions of the general concepts of anatomy written by the teacher), web lectures, formative test questions, links to scientific papers, and links to additional electronic books.

Web lectures and text selections were provided as background information and covered basic principles. Understanding of these basic principles could be checked with formative test questions. More challenging materials such as scientific papers and books were made available to encourage students to elaborate and expand their knowledge.

The students were instructed to study materials of their choice so that in-class activities could be dedicated to adjacent and more complex principles, such as specification of concepts or comprehensive discussion of difficult elements. If necessary, basic principles were clarified at the beginning of each classroom meeting by a teacher who was a content expert.

The Rheumatology and Orthopedics course had a similar setup. Blackboard® gave access to web lectures, text selections (in this course consisting of textbook fragments covering the subject matter), case studies (i.e., patient presentations), links to electronic books, and scientific papers. During in-class activities, case method teaching was applied, followed by discussion based on new case studies. A content expert teacher guided in-class activities.

Participants

Of the 40 students annually enrolling in the program, 38 participated in this study during the 2013–2014 Anatomy course, and 25 students participated in the 2014–2015 Rheumatology and Orthopedics course. These students were on average 24.0 ± 3.5 years old, and 60 % (23) were female. In total, 25 students (63 %) participated in both studies.

All participating students signed informed consent forms providing them with information about the goals and data handling methods of each study. Participation was voluntary and no incentives were given. The Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) approved these studies separately (# 284 and # 397).

Data Collection

Self-Reported Use of Online Study Materials

In both courses, learning instructions stressed that pre-class preparation was essential in order to make in-class activities successful. Students were instructed that they could choose whichever materials they preferred to use to prepare for classroom meetings. None of the information sources were presented as mandatory.

To determine students’ use of online study materials, all participants were invited to fill out a weekly questionnaire including items with 5-point Likert scales as to what extent they used which online study materials when preparing for the in-class activities. Participants were also asked to explain why they perceived their three most extensively used study materials to be supportive, in an open-ended question format. In the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course, after the collection of data of open-ended questions, closed-questions were formulated asking students to what extent they agreed with the arguments explaining why online study materials are perceived as supportive.

Learning Strategies

The following nine learning strategies were measured using the following scales of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) [7]: Rehearsal, Elaboration, Organization, Critical thinking, Self-regulation, Time management, Effort regulation, Peer learning, and Help seeking. All 50 items in the nine learning strategy scales were translated into Dutch. To determine the reliability of the translated items, 25 volunteers studying in different (bio-) medical graduate programs filled out this questionnaire. All items were to be rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true of me) to 7 (Very true of me).

The reliability of the nine scales was determined using Cronbach’s alpha. If Cronbach’s alpha was below 0.65, individual items were inspected for clarity and adapted to improve the scale. This led to rephrasing two items of the scale Effort regulation.

At the end of both courses, the questionnaire was administered to measure students’ self-reported learning strategies. Scale scores were constructed for each of the nine learning strategies.

For each learning strategy scale, normality was inspected using histograms. All scales, except for Critical thinking, appeared to be distributed normally. The distribution of Critical thinking showed a rather dichotomous pattern, suggesting two subgroups (those who do and do not indicate to think critically). Therefore, the mean scores for this scale were transformed into a dichotomous variable.

Analyses

Self-Reported Use of Online Study Materials

Due to missing data, three and five participants were excluded from the Anatomy and Rheumatology and Orthopedics course, respectively. Open-ended questions in which students explained why they perceived their three most extensively used study materials to be supportive were grounded categorized. Items with 5-point Likert scales as the use of online study materials and the agreement with explanations for perceived supportiveness of study materials were analyzed by inspection of means and standard deviations.

Differences in Study Material Use

To investigate whether students differed in the study materials they used, K-means cluster analysis was applied [22]. In the Anatomy course, one additional student was excluded due to one missing data point. We started with interpreting the three, four, and five cluster solutions, but these results showed only two meaningful clusters of students could be distinguished.

Relation Between Self-Reported Use of Study Material and Learning Strategies

To explore how the use of online study materials is related to self-reported learning strategies, bivariate correlation analysis was performed. The correlations between study material use and eight learning strategies, Rehearsal, Elaboration, Organization, Self-regulation, Time management, Effort regulation, Peer learning, and Help seeking, were analyzed for both the Anatomy and the Rheumatology and Orthopedics courses. Because the number of correlations that were analyzed was rather high (40 correlations per analysis), a conservative P value was used for significance (P < 0.01). As Critical thinking was considered a dichotomous variable, the two subgroups were compared on their use of study materials using ANOVAs.

Results

Reliability of Learning Strategies

Table 1 shows the reliabilities of the eight learning strategies. If necessary, we aimed to improve Cronbach’s alpha to ≥0.65, while maintaining as many items as possible and using identical scale items for both the Anatomy and the Rheumatology and Orthopedics courses to allow for comparisons. Based on the results in the Anatomy course, two items in the Elaboration scale were removed to increase the alpha from 0.57 to 0.65.

The Self-regulation and Help seeking scales initially showed low reliabilities in the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course (alpha = 0.61 and 0.35, respectively). Deleting one item optimized these scales to 0.65 and 0.69, respectively.

Self-Reported Use of Study Materials

Table 2 shows that in both courses, students prepare for in-class activities predominantly by watching web lectures and reading text selections. In addition, formative test questions in the Anatomy course and case studies in the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course were the third most frequently used tools to prepare for in-class activities.

Perceived Supportiveness of Web Lectures, Text, and Formative Test Questions or Case Studies

In the Anatomy course, students reported that web lectures were supportive to prepare for in-class activities because they consisted of a clearly explained summary of the content that could be paused and repeated as many times as preferred. Additionally, in the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course, students indicated that web lectures provided a clear overview of the most important topics (4.10 ± 0.77), which can be viewed at their own pace (4.43 ± 0.60).

Text selections were perceived as a summary of the content that helped students to distinguish essentials from ancillaries in the Anatomy course. Interestingly, in the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course, contradicting answers were given regarding text. In open-ended questions, students described that text selections did provide them with an overview, but they rated this characteristic rather low in the closed questionnaire (2.25 ± 1.25). They also claimed that text selections were too extensive (4.30 ± 1.33).

Formative test questions, available in the Anatomy course, were found to be supportive as students indicated that these questions helped them to check their understanding of particular subjects, and students appreciated that it is an interactive learning tool. In the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course, formative tests were not available, but instead, students could apply their knowledge by solving case studies (4.14 ± 0.73). Students reported that these case studies also helped them to focus their study effort (3.52 ± 1.03).

Differences in Study Material Use

Cluster analysis indicated that two groups of students could be distinguished based upon their self-reported study material use, referred to as A and B. Table 3 shows that in both courses, group A and B extensively watched web lectures and read text selections. In addition to these basic materials, students in group AA used more formative test questions, read more scientific papers, and studied additional books, compared to group BA. In the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course, both groups also used case studies to prepare for in-class activities. Students from group ARO read more scientific papers and studied additional books more intensively, compared to group BRO. In addition, students from group ARO seemed to read text selections more extensively, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.052). Students that clustered to group A in the Anatomy course did not necessarily cluster to group A in the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course.

Relation Between Self-Reported Use of Study Material and Learning Strategies

Two significant correlations were found for reading text selections. As shown in Table 4a and b, in the Anatomy course (see Table 4a), reading text selections was positively related to Effort regulation (i.e., ability to control study effort and committing to personal goals), suggesting that students who read more texts also reported to be committed to finish homework before class. Additionally, a positive correlation between text selections and Rehearsal in the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course (see Table 4b) suggests that students who read more texts also reported to rehearse more when studying.

Additionally, two correlations were found for the learning strategy Self-regulation. In the Anatomy course, a positive correlation was found for the use of scientific papers with Self-regulation, suggesting that students who report to be less aware of their own cognition read less scientific papers. However, it must be noted that students hardly read additional papers in general, as shown in Table 2.

In the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course, even though all students watched web lectures, as shown by the high mean and small standard deviation in Table 2, the more students reported to watch web lectures, the more they report to apply Self-regulation (i.e., the ability to plan and monitor a task; see Table 4b).

Interestingly, no significant correlations were found between learning strategies and use of formative test questions, case studies, or additional books.

The two ANOVAs comparing the two subgroups for Critical thinking showed no differences in terms of their use of online study materials. In the Anatomy course, P values were between 0.195 (F = 10.59) for text selections and 0.971 (F = 3.73) for scientific papers. In the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course, P values ranged from 0.111 (F = 2.78) for text selections and 0.818 (F = 0.83) for case studies.

Discussion

The prerequisite for a successful flipped classroom approach is that students are well prepared for participation in in-class activities. This exploratory study gives insight into the students’ predominant use of pre-class study materials. All students use web lectures and text selections extensively. Other tools such as case studies and formative test questions are used as well, but these seem to be used to a lesser extent. When preparing for in-class activities, watching web lectures is related to Self-regulation, and reading text selections is related to Effort regulation or Rehearsal.

Extensively Used Study Materials

In the flipped courses, web lectures were designed to provide students with background information and to teach basic principles. Therefore, intensive use of web lectures while preparing for in-class activities was perhaps not surprising. Students appreciated that web lectures could be viewed at their own pace, which is in line with other studies regarding the use of web lectures [23]. Moreover, web lectures provided students with an overview of the most important topics, which is supported by the fact that the use of web lectures was related to students’ self-reported ability to plan and monitor their learning.

The second most extensively used online study material was text selections. Students participating in this study have indicated that text selections helped them to summarize the content and to distinguish essentials from ancillaries. Moreover, correlation analyses suggest that information covered by text selections helped students to regulate study effort when preparing for in-class activities. However, when text selections are perceived to be too extensive, students will miss the overview of the content. This might explain why students rehearsed more.

Finally, formative test questions, case studies, and additional study materials such as scientific papers and books were provided to stimulate students to elaborate and encourage them to think critically. However, relations between the use of these more challenging study materials and cognitive more complex learning strategies (i.e., Elaboration and Critical thinking) were not found. Students’ choice to mainly prepare with “basic materials” (web lectures and text) might be explained by the fact that students perceived to be overloaded, as indicated by comments in the end-of-course evaluations.

Differences in Study Material Use

Street et al. argued that students have different learning preferences and that, therefore, various study materials should be provided to students [8]. However, our findings indicate that all students use the same basic materials to prepare for in-class activities and that half of the students used additional materials. We thus did not find that students seem to have preferences for different study materials, but mainly differ in the extent to which they use more challenging materials in addition to the basic materials. Also, the fact that students’ individual use of materials was not consistent between the two courses does not support the notion of students having personal learning preferences.

With respect to the issue of whether providing web lectures as pre-class preparation would be enough for students in a flipped classroom to prepare for in-class activities, our findings suggest that web lectures are important. We showed that students intensively used this material to prepare for in-class activities, similar to reading text selections. However, since 40 to 50 % of the students chose to combine these basic materials with scientific papers, books, and formative test questions (if available), our data do not support the idea that web lectures alone are sufficient to prepare for student-centered in-class activities. Neither do our findings support the hypothesis that students use a selection of the available learning materials to accommodate their personal learning preferences. Therefore, it is advised to provide students clear study directions to prevent undue study load and time commitments.

Relation Between Self-Reported Use of Study Material and Learning Strategies

In the Anatomy course, three moderately strong correlations were found (r > 0.4), whereas 12 moderate or strong correlations were detected in the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course. Interestingly, the strongest correlation involving the use of text selections and rehearsal observed in the clinical course was absent in the basic science course. One of the underlying causes might be the nature of these text selections. In the Rheumatology and Orthopedics course, revising text selections could contribute to students understanding of the content, whereas the text selections in the Anatomy course could do this to a lesser extent as they are related to more general concepts. Another explanation might be that students adapt their learning strategies when learning different subjects. This is in line with the findings of Rotgans and Schmidt, who showed that learning strategies are context-specific and, therefore, large within-person variations can be measured across different disciplines [24].

Study Limitations

While our results provide useful information for selecting extensively used study materials, a number of limitations should be addressed. First, the small number of students participating in this study together with the large number of correlations that were reported to explore the relation between students’ use of study materials and their learning strategies affect the generalizability of the results. This approach may have led to capitalization on chance, even though a conservative P value of ≤0.01 was used to determine statistically significant differences. Therefore, to validate our conclusions, this study should be replicated in larger and more heterogeneous samples.

Second, to explore to what extent study materials were used, questionnaires were composed of Likert scale questions. This provided information about the self-reported relative use of study materials, although it is not addressed specifically how much time students spend using the different materials. Future research might focus on this to investigate to what extent flipping the classroom does affect time commitment and to determine to what extent study load does increase when a larger variety of study materials is available as anticipated by Moffett, Prober, and Street [1, 8, 14]. This will provide insight into the relation between students perceived and experienced study load.

A third limitation concerns the fact that offline study materials were not included in this study. This decision was made because this study aimed to distinguish which online study materials are used most frequently, since the online materials are the materials provided by teachers. This is important because it is known that flipping the classroom requires a large time and effort investment from the teachers [1].

Study Strengths

Our study has a number of strengths. It describes student preparation in two distinct courses (a basic science and a clinical course) in which students predominantly used the same study materials. This suggests that the findings are robust for at least our population. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to explore differences between the materials that students use to prepare and the relation between students’ preparation and their learning strategies. Therefore, this study has provided some first insights into these issues but also yielded directions for future research.

In conclusion, students do not seem to differ a lot in how they prepare for in-class activities as most students seem to prepare by watching web lectures and reading text selections. Additionally, approximately half of the students do use formative test questions, scientific papers, and books next to these basic study materials. Unexpectedly, these cognitive challenging study materials were not related to deep learning strategies. Instead, pre-class preparation using web lectures and text selections were related to learning strategies that involve regulation and monitoring of study effort.

References

Moffett, J. Twelve tips for “flipping” the classroom. Med Teach, 2014: p. 1–6.

Bishop, J.L. and Verleger M.A, The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. 120th ASEE Annual conference & exposition, 2013: p. 18.

Mehta NB et al. Just imagine: new paradigms for medical education. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1418–23.

Galway LP et al. A novel integration of online and flipped classroom instructional models in public health higher education. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(181):9.

Moraros J et al. Flipping for success: evaluating the effectiveness of a novel teaching approach in a graduate level setting. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):317.

Sharma N et al. How we flipped the medical classroom. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):327–30.

Pintrich, P.R., et al. A manual for the use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). 1991.

Street SE et al. The flipped classroom improved medical student performance and satisfaction in a pre-clinical physiology course. Med Sci Educ. 2015;25:9.

Moravec M et al. Learn before lecture: a strategy that improves learning outcomes in a large introductory biology class. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2010;9(4):473–81.

Prober CG, Heath C. Lecture halls without lectures—a proposal for medical education. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(18):1657–9.

Moffett J, Mill AC. Evaluation of the flipped classroom approach in a veterinary professional skills course. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:415–25.

Wong TH et al. Pharmacy students’ performance and perceptions in a flipped teaching pilot on cardiac arrhythmias. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;10(78):6.

McLaughlin JE et al. Pharmacy student engagement, perfomance, and perception in a flipped satellite classroom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(9):8.

Prober CG, Khan S. Medical education reimagined: a call to action. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1407–10.

Reis, R. Flipped Classrooms—old or new? Tomorrow’s Professor eNewsletter, 2013(1299): p. 3.

Kachka, P. Understanding the flipped classroom: part 2. GFaculty Focus, Magna Publications, 2012. October.

Herreid C, Schiller NA. Case studies and the flipped classroom. J Coll Sci Teach. 2013;42(5):5.

McLaughlin JE et al. The flipped classroom: a course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):236–43.

Sappington J, Kinsey K, Munsayac K. Two studies of reading compliance among college students. Teach Psychol. 2002;29(4):3.

Robin BR et al. Preparing for the changing role of instructional technologies in medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):435–9.

Masters K, Ellaway R. e-Learning in medical education guide 32 part 2: technology, management and design. Med Teach. 2008;30(5):474–89.

Jain AK. Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means. Pattern Recogn Lett. 2010;31(8):651–66.

McNulty JA et al. An analysis of lecture video utilization in undergraduate medical education: associations with performance in the courses. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:6.

Rotgans J, Schmidt H. Examination of the context‐specific nature of self‐regulated learning. Educ Stud. 2009;35(3):239–53.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the course coordinators, R.L.A.W. Bleys, I.E. Thunnissen, and J.J. Verlaan, for their cooperation and to adapt the educational approach to flipped classroom. We also would like to thank I.E.T. van den Berg for her initial discussions on the design of the flipped classroom and preliminary results, and most importantly, the undergraduate medical students for their participation in both studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) approved these studies separately.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bouwmeester, R.A.M., de Kleijn, R.A.M., ten Cate, O.T.J. et al. How Do Medical Students Prepare for Flipped Classrooms?. Med.Sci.Educ. 26, 53–60 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0184-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0184-9