Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) affects approximately 14.8 million adults in the United States, which is about 6.7 % of the US population. MDD impacts most activities of daily living, including oral hygiene practices and use of dental resources. This review article provides information related to underlying mechanisms of disease, diagnosis, and treatment so that dentists may best address patients’ dental concerns in the context of underlying depression. Laboratory and psychological screening tools are also discussed in relation to specific practice recommendations for managing patients with MDD as well as identifying patients with underlying symptoms who may be at risk for MDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression affects all communities and is estimated to afflict 350 million people throughout the world. The World Health Organization noted that, in 2012, 1 in 20 people experienced depression in the previous year [1]. In the United States (US), the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study identified a lifetime prevalence of depression at 16.5 %, with 6.7 % of US adults reporting depression within the last 12 months. For these individuals, 30.4 % are classified as having severe depressive disorders, which represents 2.0 % of the US population [2]. The average age of onset of major depression is identified as 32 years old [3, 4]. According to the 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study, depression is the second leading cause of years lived with disability (YLD), accounting for 8.2 % of global YLDs, and the leading cause of disability adjusted life years (DALY), accounting for 2.5 % [5].

Minor changes to the criteria for MDD were released by the American Psychiatric Association in May 2013 [6]. The major diagnostic criteria for MDD remain, and are as follows:

-

At least five of the nine following specific symptoms present nearly every day: depressed mood or irritable, decreased interest or pleasure, significant weight change (greater than 5 % or change in appetite), change in sleep, change in activity, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of guilt/worthlessness, impaired concentration, or suicidality or recurrent thoughts of death

-

At least one of the symptoms is either depressed mood or loss of interest/pleasure

-

Symptoms represent a change from previous functioning

-

Symptoms cause “clinically significant distress” in social, occupational, or other important settings

-

Does not include symptoms that are clearly due to a general medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism) or to the direct physiologic effects of a substance (medication or drug of abuse)

Additional modifications of the criteria for MDD reclassify dysthemia (a form of chronic mild depression) to include it as a part of chronic depression and consider bereavement in making a diagnosis of MDD [7].

Substance abuse disorders are common among those individuals with MDD [8], and the most serious outcome of depressive disorders is suicide, the psychiatric disorder most commonly linked with depression, with a 20 % greater risk of suicide in those with depression than in the general population. For example, two out of three individuals who complete suicide are depressed, whereas, approximately seven of 100 men and one of 100 women, who have been diagnosed with depression in their lifetime, will complete suicide [9]. Anxiety [10–13], pain [14–16], diabetes [17, 18], and cardiovascular diseases [19] have also been linked as comorbid conditions with major depressive disorder.

Recent studies have highlighted the association between depression and oral health behaviors and oral health status. Poor periodontal health has been identified with depression based on both biologic and behavioral mechanisms. Biological mechanisms include the association between depression and the inhibition of immune function, as well as the discovery of the association between anti-depressant medication and the growth of specific bacteria [20•]. Psychological distress has been associated with lower toothbrushing frequency and frequent consumption of sugary products [21•], and is a risk factor for impaired gingival status and self-report of bleeding gums [22•], dental caries [23], tooth loss [24], edentulism [22•, 25•], and TMD pain [26].

Perhaps most intriguing are the findings that depression is associated with fear of dental treatment [10, 22•, 27–30]. In a recent study by Lenk et al. [27], nearly a third of patients (n = 64) in their psychometric service had a severe fear of dental treatment compared to only four percent of control subjects, and patients accepted for treatment of depressive disorders were five times more likely to fear dental treatment. Of note, over one half of these patients had cancelled or failed to keep dental appointments due to this fear.

Mechanisms of Disease

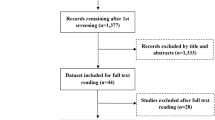

Major depressive disorder has multiple causal components. A discussion of five “levels” of disease mechanisms for depression is presented in Fig. 1, and is elucidated below.

Level 1 Genes and proteins

Decades of research on the genetic basis of depression confirms that there is a definite inherited aspect of MDD [31, 32•], with one recent study also demonstrating the increased impact of heritability in women vs. men [33]. However, both genome-wide association studies and candidate gene studies have yet to identify any definitive genetic mechanisms. One possible explanation of the discordance between these two findings is the plausibility that MDD subtypes represent distinct genetic disorders [32•]. Without a clear gene-specific association, researchers have also begun to study the role of proteins that regulate gene expression, such as that of histone acetylation and methylation [34, 35].

Level 2 Neurotransmitters and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis

While low levels of the three major monoamines -serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine- have all been related to symptom expression in MDD, these neurotransmitters appear to work in concert and no single neurotransmitter has been found to be in ultimate control [35]. Evidence for the influence of serotonin includes the reduction of serotonin transporter (SERT) binding sites and 5HT receptor subtypes in individuals with MDD, and the existence of successful serotonin-targeted MDD treatments (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs). Dopamine, while more commonly associated with schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease, has also been shown to be associated with the anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure) experienced by individuals with MDD [36, 37]. The norepinephrine system may interact with the serotonin system in regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors have been particularly successful in treating MDD resistant to more common therapies [38].

The HPA axis has also been directly implicated in MDD [17, 35, 39, 40]. The HPA axis, which regulates the body’s response to stress through the production and response to endogenous steroids, has an impact on, among other things, a person’s immune system, mood/emotion, and energy, all of which are also factors in the diagnosis of MDD. Individuals with MDD have been shown to have heightened activity of their HPA axes, while experimental manipulation of HPA axis functions in animal models induces depressive-like symptoms. Furthermore, anti-depressive medication has been shown to have an effect on modulating HPA axis activity [41].

Level 3 Emotions, cognitions, and pain

Emotions and cognitions are at the heart of the diagnosis of MDD. While research is ongoing to identify Level 1 and Level 2 criteria for the diagnosis of MDD, it is at Level 3 in this model that the current diagnostic criteria begin to manifest. Level 3 is also the target of cognitive therapies in the treatment of MDD [42, 43]. Depression is associated with “increased elaboration of negative information, difficulties in cognitive control when processing this information, and difficulties disengaging from this information” [44]. Resilient individuals, or those who have a more positive cognitive approach to adversity (e.g., acceptance, positive refocusing, positive reappraisal), have been shown to be less susceptible to and have more favorable treatment outcomes with MDD [45].

MDD is also associated with general anxiety disorders [12, 13, 30, 46] and with pain [14, 47], both of which are thought to have shared genetic factors, biological pathways, and neurotransmitters [48]. The co-presentation of MDD symptoms and pain has been termed the “depression-pain syndrome,” which is where “people who are in pain are more likely to be depressed, and people who are depressed are more likely to have pain” [48]. At level 3, dental specific dysregulation also begin to present. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and pain are all associated with sleep bruxism and tooth wear [49], and the association between depression and dental specific fear has been briefly addressed earlier in this paper.

Level 4 Personal habits and social environmental factors

In addition to the mechanisms of MDD that are internal to the person suffering from the disorder, there are also causal factors of MDD that exist in a person’s environment, either through the intrapersonal environment a person creates for him or herself through personal habits and behaviors, or the interpersonal environments a person inhabits both through their immediate relationships and through their broader social and economic situations.

Because MDD causes an interruption in health behavior patterns, behavioral therapies work to reestablish the healthy patterns to ameliorate the underlying depression [50]. For example, there is some evidence that changing a person’s exercise habits may be more effective than either cognitive-based psychological or pharmacological therapies [51]. People with MDD may also have poor sleep and nutritional habits [40], of which the nutritional habits in particular may worsen dental health [52•].

Both socioeconomic status (SES) [53–56] and geography [3, 5] have an effect on diagnosis and treatment of MDD, but also have more direct causal implications such as greater likelihood of experiencing violence/trauma and upheaval in certain countries, regions, and SES groups [57]. While the presentation of MDD (e.g., low moods, sadness, and trouble sleeping) remains similar across different groups of persons, interpersonal and broader social, economic, and cultural situations, however, are nearly impossible to address via the common interventions (either cognitive/behavioral or pharmacologic) that target suffering individuals.

Level 5 Stress and Inflammation

Inflammation may be a major underlying factor linking MDD to other medical comorbidities. Individuals at higher risk for developing depression include those living with chronic diseases, most notably cardiac diseases [58, 59] and diabetes [18]. The elderly, also, are at almost twice the risk for MDD as in the general US population [60]. Recently research has begun to investigate the underlying role of inflammation in all of these illnesses, as well as of the aging process more generally [61]. Depression is also associated with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and Interleukin-1, and C-reactive protein [40, 61–64]. Furthermore, in at least one study, anti-inflammatory agents have been shown to reduce depressive symptoms [61].

Chronic stress is another, and perhaps the ultimate [65•] major factor linking all of the earlier levels in the mechanisms of MDD. Evidence of stress exists at all levels, from the genetic and cellular, to environmental [66–68]. Stress is correlated with inflammation, and stress reduction may occur through cognitive and behavioral therapies for MDD such as cognitive reframing or exercise. Therefore, by reducing stress in the dental chair and dental related anxiety, dentists may contribute to improving the trajectories of MDD.

Treatment

Both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, in combination or separately, have proven effective treatment for MDD [69]. Thorough and complete medical histories are needed to identify all depression management strategies for a dental patient in order to prevent complications with dental care, most notably medication side effects, potential adverse drug interactions, and the appropriate use of vasoconstrictors in administering local anesthesia [70].

Common anti-depressants prescribed for depression include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic anti-depressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and atypical anti-depressants. Possibly effective home care treatments are herbal preparations (e.g., St. John's wort), omega-3 fatty acids, S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe), and folate, which have all shown an effect greater than placebo [71, 72]. Non-pharmacological treatment strategies include psychotherapy (interpersonal and cognitive behavior therapy), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) [73], and transmagnetic therapy (TMS). Effective complementary treatment may include exercise, relaxation, and yoga [74, 75].

The most common dental side effect present with current anti-depressant medications is xerostomia [73]. Dental side effects for SSRI anti-depressant medications also include dysgeusia, stomatitis, glossitis, sialedenitis, discolored tongue, tongue edema, bruxism, and angular chelitis. Most TCA medications produce sialadenitis and dysgeusia as side effects. Atypical anti-depressant side effects may include gingivitis, fungal infections, oral ulcers, and halitosis [76, 77].

Dentists should also be aware of drug interactions with common anti-depressant therapy. SSRIs have been associated with bleeding events such as bruising, hematoma, petechiae, purpura, and epistaxis due to a suspected anti-platelet effect; however, the lack of randomized, controlled clinical trials limits causal reference at this time [78–80]. TCAs combined with vasoconstrictors or sympathomimetics have the potential for association with cardiovascular adverse drug reactions, including orthostatic hypotension episode [77]. MAOIs have a dangerous, concomitant effect with opioids (meperidine, tramadol, and propoxyphene) and must be avoided due to induction of a serotonin-like syndrome manifested by tremors, convulsions, muscle rigidity, and hyperexia [80]. St. John's Wort adds to the photosensitizing effect of amitriptyline, sulfa drugs, and tetracycline, and, because of its induction of the CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 enzymes, will decrease drug absorption of many drugs used in dental settings (e.g., acetaminophen, diazepam, and ketoconazole) as well as of other common medications [81].

Screening for MDD

The characteristics of MDD are many and generally well accepted by experts in the field. Many primary health practitioners and most dentists have neither the expertise nor the time to conduct a specialist-level interview with a patient to determine whether or not MDD might be affecting his/her daily life and oral health. A screening tool that enables timely referral and appropriate follow-up treatment has the potential to facilitate improved home care, better acceptance of treatment, and a generally enhanced dental office experience for the patient.

Laboratory Tests for MDD

Ideally, a diagnostic blood or saliva laboratory test would accurately identify all MDD patients with a minimum of false positives. Although some progress on this front has been reported in the popular press, at this time no definitive laboratory test exists for MDD. Testing of saliva continues to be examined by researchers for its potential value as a part of periodic medical and dental examinations [82]. Saliva has been used to test for cortisol levels as an indicator of chronic stress in healthy patients [83]. Elevated salivary cortisol levels have been identified in depressed patients [84, 85]. Nevertheless, cortisol levels in saliva can suggest other, non-mental health conditions as well, and while its non-invasive nature and ease of collection make salivary diagnostics extremely attractive, much work remains to be done before an effective and reliable screening tool using saliva is available [86].

Many of the laboratory tests used by primary care physicians when MDD is being considered as part of a differential diagnosis are used to rule out potential physical causes of depression include: overactive thyroid, hypothyroid, multiple sclerosis, head trauma, stroke, and corticosteroid treatment. Tests done to rule out organic causes of MDD include: complete blood count, thyroid stimulating hormone, vitamin B-12, rapid plasma reagin, HIV virus, electrolytes (calcium, phosphate, magnesium), blood urea nitrogen, liver function, blood alcohol, blood and urine toxicity screens, arterial blood gases, dexamethasone suppression, and adrenocorticotropic hormone [73]. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that MDD can coexist with related organic causes and often, in such cases, only somatic symptoms are evident.

Psychological Tests for MDD

Good evidence supports the combination of screening for depression with appropriate follow-up. O’Connor and others have stressed the critical importance of additional staff in providing at least some of the follow-up care in lieu of the overburdened primary care physician [87]. A variety of screening tools have been developed for use in primary care settings [88], and, perhaps, the easiest yet effective tool for the busy dentist or general practitioner to add to his/her armamentarium would be the two question version of the PHQ (PHQ-2). The questions involve: little interest or pleasure in doing things (0-3) and feeling down, depressed or hopeless (0-3) [89]. Arrol found in general medical practices in New Zealand that asking these questions orally, rather than having the patient complete a written questionnaire, was more effective in identifying cases of depression. He argues that the relatively low specificity of the test (67 %) is offset by follow-up interviews [90]. The dentist could easily incorporate these two questions into a patient interview and then, in conjunction with the patient, make a recommendation for follow-up with the patient’s primary care physician or a mental health professional. It should be noted that, despite studies to the contrary, a review by Gilbody concluded that routine screening alone has minimal impact on depression outcomes and that a two stage process (screening + follow-up) needs evaluation in future research [91].

Conclusion

As noted by Korszun and Ship (1997) [15] and still relevant today,

… the diagnosis and treatment of depression should be especially relevant to dental practitioners because they are primary care providers who treat a large cross-section of the community … Dentists should be familiar with the clinical manifestations of depression which could assist in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic facial pain… Although not psychiatrists, dentists can screen (emphasis added) for symptoms of depression.

Dentists are in a unique position to identify symptoms associated with depression in their patients, and to contribute to their patients’ overall wellness through discussion and referral. For example, careful observation of the patient, combined with the completion of a thorough medical history that includes an appropriate MDD screening tool such as the PHQ-2, may reveal underlying symptoms of depression for further evaluation. Careful probing of patients with comorbid conditions related to MDD, such as dental fear, pain and unmet dental disease, may elucidate symptoms of depression and merit referral to the primary care physician and/ or a mental health professional. Dentists who provide a caring and empathetic atmosphere are most important in gaining the trust of all patients, especially those with MDD. Developing professional rapport with a patient’s general medical practitioner is particularly important if referral of suspected MDD is considered. Alternatively or additionally, a dentist may wish to develop an ongoing relationship with a trusted mental health professional to whom patients could be referred. In most cases, referral to the family physician may be better accepted by the patient; however, the availability of both options provides more flexibility in dealing with individual situations. Additional circumstances, suggested below, may provoke inquiry into whether or not a patient has underlying MDD.

-

Does the patient express extreme fear of dental treatment?

-

Does the patient present with sleep bruxism and or TMJ pain?

-

Does the patient have excessive decayed, missing, or abraded/abfracted teeth?

-

Is the patient a Type II diabetic or does she/he have cardiovascular disease?

-

Does the patient present with any unexplainable dental complaints, including extreme dissatisfaction with the appearance of their teeth or intermittent pain of unknown origin?

-

Does the patient present with poor oral hygiene that is inconsistent with their overall appearance and self-presentation?

The recommendations of Frielander and Mahler, published in the Journal of the American Dental Association in 2001, remain a relevant guide for the general dentist in the dental implications of the medical management of MDD. The general dentist, if desired, may even have a more direct role in the treatment of MDD. General dentists may consult with a patient’s primary physician or psychiatrist, monitor medication adherence and dental treatment strategies, and utilize techniques in the dental office to reduce MDD associated dental anxiety. Treatment of patients with MDD is facilitated by having a well-informed and trained dental staff that understands and empathizes with patients who may have MDD. This type of support goes a considerable way to help patients deal with MDD and its frequent dental sequelae.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Marcus M, Yasamy MT, van Ommeren M, Chisholm D, Saxena S. Depression a global public health concern [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2012 [cited 2013 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/who_paper_depression_wfmh_2012.pdf.

National Institute of Mental Health. Major depressive disorder among adults [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2014 Mar 21]. Available from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/1mdd_adult.shtml.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289:3095–105.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Replication (NCS-R). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602.

Ferrari AJ, Somerville AJ, Baxter AJ, Norman R, Patten SB, Vos T, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and incidence of major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Psychol Med. 2013;43:471–81.

American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 development [Internet]. [cited 2014 Mar 20]. Available from: www.dsm5.org.

American Psychiatric Association. Highlights of changes from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5 [Internet]. American Psyciatric Publishing; 2013 [cited 2014 Mar 22]. Available from: www.dsm5.org.

Thomas AC, Staiger PK. Introducing mental health and substance use screening into a community-based health service in Australia: usefulness and implications for service change. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20:635–44.

American Association of Suicidology. Suicide and depression [Internet]. [cited 2012 Mar 21]. Available from: www.suicidology.org.

Pohjola V, Mattila AK, Joukamaa M, Lahti S. Anxiety and depressive disorders and dental fear among adults in Finland. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119:55–60.

Marques-Vidal P, Milagre V. Are oral health status and care associated with anxiety and depression? A study of Portuguese health science students. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66:64–6.

Teachman BA, Joormann J, Steinman SA, Gotlib IH. Automaticity in anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;575–603.

Goldberg D, Fawcett J. The importance of anxiety in both major depression and bipolar disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:471–8.

Celić R, Braut V, Petricević N. Influence of depression and somatization on acute and chronic orofacial pain in patients with single or multiple TMD diagnoses. Coll Antropol. 2011;35:709–13.

Korszun A, Ship JA. Diagnosing depression in patients with chronic facial pain. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:1680–6.

Hirsch C, Türp JC. Temporomandibular pain and depression in adolescents–a case-control study. Clin Oral Investig. 2010;14:145–51.

Stetler C, Miller GE. Depression and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activation: a quantitative summary of four decades of research. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:114–26.

Cox DJ, Gill Taylor A, Dunning ES, Winston MC, Van Luk IL, McCall A, et al. Impact of behavioral interventions in the management of adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13:860–8.

Thombs B, De Jonge P. Depression screening and patient outcomes in cardiovascular care. JAMA. 2008;300:2161–71.

Khambaty T, Stewart JC. Associations of depressive and anxiety disorders with periodontal disease prevalence in young adults: analysis of 1999-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45:393–7. This article provides evidence of an association between mood disorders and periodontal disease with tobacco use as a potential mediator of the relationship.

Park SJ, Ko KD, Shin S-I, Ha YJ, Kim GY, Kim HA. Association of oral health behaviors and status with depression: results from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2010. J Public Health Dent. 2013;2030:1–12. This article provides evidence of the association between depression and oral health status after adjusting for oral health behaviors.

Armfield JM, Heaton LJ. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: a review. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:390–407. This review article provides detailed information on how to manage fear and anxiety in dental patients.

Hugo FN, Hilgert JB, de Sousa MDLR, Cury JA. Depressive symptoms and untreated dental caries in older independently living South Brazilians. Caries Res. 2012;46:376–84.

Okoro CA, Strine TW, Eke PI, Dhingra SS, Balluz LS. The association between depression and anxiety and use of oral health services and tooth loss. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:134–44.

Saman DM, Lemieux A, Arevalo O, Lutfiyya MN. A population-based study of edentulism in the US: does depression and rural residency matter after controlling for potential confounders? BMC Public Health. 2014;14:65. This article utilizes a U.S. national database (BRFSS) to demonstrate an association between current depression and edentulism.

Lopes SLPC, Costa ALF, Cruz AD, Li LM, de Almeida SM. Clinical and MRI investigation of temporomandibular joint in major depressed patients. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012;41:316–22.

Lenk M, Berth H, Joraschky P, Petrowski K, Weidner K, Hannig C. Fear of dental treatment–an underrecognized symptom in people with impaired mental health. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:517–22.

Smith TA, Heaton LJ. Fear of dental care: are we making any progress? J. Am Dent Assoc 2003;1101–8.

Bernson JM, Elfström ML, Hakeberg M. Dental coping strategies, general anxiety, and depression among adult patients with dental anxiety but with different dental-attendance patterns. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121:270–6.

Stenebrand A, Wide Boman U, Hakeberg M. Dental anxiety and symptoms of general anxiety and depression in 15-year-olds. Int J Dent Hyg. 2013;11:99–104.

Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1552–62.

Flint J, Kendler KS. The genetics of major depression. Neuron. 2014;81:484–503. This review article provides current evidence for the role of genetics in depression.

Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:109–14.

Sun H, Kennedy PJ, Nestler EJ. Epigenetics of the depressed brain: role of histone acetylation and methylation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:124–37.

Saveanu R, Nemeroff C. Etiology of depression: genetic and environmental factors. Psychiatr Clin North Am Elsevier. 2012;35:51–71.

Tye K, Mirzabekov J, Warden M, Ferenczi E, Tsai H, Finkelstein J, et al. Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature. 2013;493:537–41.

Haenisch B, Bönisch H. Depression and antidepressants: insights from knockout of dopamine, serotonin or noradrenaline re-uptake transporters. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;129:352–68.

Goddard AW, Ball SG, Martinez J, Robinson MJ, Yang CR, Russell JM, et al. Current perspectives of the roles of the central norepinephrine system in anxiety and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:339–50.

Belvederi Murri M, Pariante C, Mondelli V, Masotti M, Atti AR, Mellacqua Z, et al. HPA axis and aging in depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;46–62.

Lopresti AL, Hood SD, Drummond PD. A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: diet, sleep and exercise. J. Affect. Disord. 2013. p. 12–27.

Anacker C, Zunszain PA, Cattaneo A, Carvalho LA, Garabedian MJ, Thuret S, et al. Antidepressants increase human hippocampal neurogenesis by activating the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:738–50.

Bowins B. Cognitive regulatory control therapies. Am J Psychother. 2013;67:215–36.

Churchill R, Moore T, Furukawa T, Caldwell D, Davies P, Jones H, et al. ‘Third wave’ cognitive and behavioural therapies versus treatment as usual for depression (Review). Cochrane Libr 2013;10.

Kircanski K, Joormann J, Gotlib IH. Cognitive aspects of depression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2012;3:301–13.

Min J-A, Yu JJ, Lee C-U, Chae J-H. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies contributing to resilience in patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;1190–7.

Pekkan G, Kilicoglu A, Hatipoglu H. Relationship between dental anxiety, general anxiety level and depression in patients attending a university hospital dental clinic in Turkey. Community Dent Health. 2011;149–53.

Drangsholt MT. Psychological characteristics such as depression, independent from a known genetic risk factor, increase the risk of developing temporomandibular disorder pain. J Evid-Based Dent Pract. 2008;8:240–1.

Gambassi G. Pain and depression: the egg and the chicken story revisited. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;1 Suppl 1:103–12.

Ahmed KE. The psychology of tooth wear. Spec Care Dentist. 2012;33:28–34.

Shinohara K, Honyashiki M, Imai H, Hunot V, Dm C, Davies P, et al. Behavioural therapies versus other psychological therapies for depression (Review). Cochrane Libr. 2013;10.

Cooney G, Dwan K, Greig C, Lawlor D, Rimer J, Waugh F, et al. Exercise for depression (Review). Cochrane Libr. 2013

O’Neil A, Berk M, Venugopal K, Kim S-W, Williams LJ, Jacka FN. The association between poor dental health and depression: findings from a large-scale, population-based study (the NHANES study). Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;7–11. This article utilizes a U.S. national database (NHANES) to provide evidence of the association between depression and oral health status after adjusting for C-reactive protein levels and body size.

Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka L. Socio-economic status, family disruption and residential stability in childhood: relation to onset, recurrence and remission of major depression. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1341–55.

Moustgaard H, Joutsenniemi K, Martikainen P. Does hospital admission risk for depression vary across social groups? A population-based register study of 231,629 middle-aged Finns. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:15–25.

Muntaner C, Ng E, Vanroelen C, Christ S, Waton WW. Social stratification, social closure, and social class as determinants of mental health disparities, 2nd ed. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, Bierman A, editors. Handb Sociol Ment Heal. 2013;205–27.

Walsh S, Levine S, Levav I. The association between depression and parental ethnic affiliation and socioeconomic status: a 27-year longitudinal US community study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1153–8.

Baxter A, Scott K, Ferrari AJ, Norman RE, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Challenging the myth of an “epidemic” of common mental disorders: trends in the global prevalence of anxiety and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2014 Jan 21.

Holt R, Phillips D, Jameson K. The relationship between depression, anxiety and cardiovascular disease: findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:84–90.

Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Baldwin RC, Connolly MJ. Depression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principles. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:1209–21.

Alexopoulos GS, Morimoto SS. The inflammation hypothesis in geriatric depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1109–18.

Rosenblat JD, Cha DS, Mansur RB, McIntyre RS. Inflamed moods: a review of the interactions between inflammation and mood disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol Psychiatry. 2014.

Pan A, Sun Q, Okereke O. Depression and risk of stroke morbidity and mortality. JAMA. 2011;306:1241–9.

Iseme RA, McEvoy M, Kelly B, Agnew L, Attia J, Walker FR. Autoantibodies and depression Evidence for a causal link? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;62–79

Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:732–41.

Roy A, Campbell MK. A unifying framework for depression: bridging the major biological and psychosocial theories through stress. Clin Invest Med. 2013;36:E170–90. This review article considers the role of stress in depression and reviews many other current theories in the mechanisms of depressive diseases.

Refulio Z, Rocafuerte M, de la Rosa M, Mendoza G, Chambrone L. Association among stress, salivary cortisol levels, and chronic periodontitis. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2013;43:96–100.

Marin M-F, Lord C, Andrews J, Juster R-P, Sindi S, Arsenault-Lapierre G, et al. Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;96:583–95.

Hill MN, Hellemans KGC, Verma P, Gorzalka BB, Weinberg J. Neurobiology of chronic mild stress: parallels to major depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:2085–117.

Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Phillips ML. Major depressive disorder: new clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet. 2012;379:1045–55.

Friedlander AH, Mahler ME. Major depressive disorder: psychopathology, medical management, and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:629–38.

Nahas R, Sheikh O. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:659–63.

Freeman MP, Mischoulon D, Tedeschini E, Goodness T, Cohen LS, Fava M, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of patient characteristics, placebo-response rates, and treatment outcomes relative to standard antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:682–8.

Mann JJ. The medical management of depression. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1819–34.

Jorm AF, Morgan AJ, Hetrick SE. Relaxation for depression. Cochrane Libr 2008;4.

Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:1068–83.

Verma A, Yadav S, Sachdeva A. Dental consequences and management in patients with major depressive disorder. J Innov Dent. 2011;1.

Keene JJ, Galasko GT, Land MF. Antidepressant use in psychiatry and medicine: importance for dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:71–9.

Wynn RL. Antidepressant drugs: new reports on adverse effects and efficacy. Gen Dent. 58:474–7.

Napeñas JJ, Hong CHL, Kempter E, Brennan MT, Furney SL, Lockhart PB. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and oral bleeding complications after invasive dental treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:463–7.

Hersh EV, Balasubramaniam R, Pinto A. Pharmacologic management of temporomandibular disorders. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008;20:197–210.

Radler DR. Dietary supplements: clinical implications for dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:451–5.

Wong D. Salivary diagnostics powered by nanotechnologies, proteomics and genomics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:313–21.

Takai N, Yamaguchi M, Aragaki T, Eto K, Uchihashi K, Nishikawa Y. Effect of psychological stress on the salivary cortisol and amylase levels in healthy young adults. Arch Oral Biol. 2004;49:963–8.

Hinkelmann K, Botzenhardt J, Muhtz C, Agorastos A, Wiedemann K, Kellner M, et al. Sex differences of salivary cortisol secretion in patients with major depression. Stress. 2012;15:105–9.

Hinkelmann K, Moritz S, Botzenhardt J, Muhtz C, Wiedemann K, Kellner M, et al. Changes in cortisol secretion during antidepressive treatment and cognitive improvement in patients with major depression: a longitudinal study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:685–92.

Inder WJ, Dimeski G, Russell A. Measurement of salivary cortisol in 2012 - laboratory techniques and clinical indications. Clin Endocrinol. 2012;77:645–51.

O’Connor EA, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Gaynes BN. Screening for depression in adult patients in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:793–803.

Gilbody S, House A, Sheldon T. Screening and case finding instruments for depression (Review). Cochrane Libr. 2005;4.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire-2 of a two-item screener validity depression. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–92.

Arroll B, Khin N, Kerse N. Screening for depression in primary care with two verbally asked questions: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;327.

Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596–602.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Ms. Kari Hexem, Mr. Robert Ehlers, Dr. Joan Gluch, and Dr. Robert Collins each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hexem, K., Ehlers, R., Gluch, J. et al. Dental Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Curr Oral Health Rep 1, 153–160 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40496-014-0020-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40496-014-0020-0