Abstract

One challenging area of speech-language pathology is evaluating treatment change in children with speech sound disorder (SSD) with a motor basis. A clinician’s knowledge and use of outcome measures following treatment are central to evidence-based practice. This narrative review evaluates the use of outcome measures to assess treatment change in motor-based SSDs. Seven databases were searched to identify studies reporting outcomes of treatment in SSDs between 1985 and 2014. Sixty-six studies were identified for analysis, and reported outcome measures were categorized within the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework (ICF-CY). The majority of studies used perceptual methods (despite their limitations) to evaluate change at the impairment level of the ICF-CY and only three studies examined participation level factors. Accurate outcome measures that reflect the underlying deficit of the SSD as well as activity/participation level factors need to be implemented to document intervention success in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Outcome measures in speech-language pathology (SLP) are an essential component of assessing treatment efficacy, monitoring progress during intervention and planning future treatment [1]. The ASHA scope of practice in SLP has highlighted that a clinician’s use of outcome measures is central to evidence-based practice [2]. The measurement of treatment change is of interest to both clinicians and researchers in SLP [3]. It is not always clear, however, from research literature how treatment change should be measured. Specifically, it is difficult to ascertain which behaviours should be measured and how measurement should be carried out.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children and Youth Version (ICF-CY) provides a conceptual framework for measuring health and disability factors at individual and population levels [4]. The ICF-CY not only encompasses impairment level factors (body structure and function) but also considers the impact of these from a broader social perspective in terms of changes in children’s activities and participation. In addition, potential environmental and personal factors that interfere with a child’s ability to communicate and participate in their home and/or community are considered [4–10]. The ICF-CY has been applied broadly in many areas of SLP, including assessing performance of children with speech impairment, children who stutter and developmental language impairment [6, 11, 12].

One area of SLP that is challenging for clinicians and researchers to evaluate treatment change is children with SSD with a speech motor control component [1]. Their speech difficulties arise from an impairment of the neuromuscular and/or motor control system and lead to difficulty in planning and executing speech sounds [13]. Their speech is characterized by deletions, substitutions and distortions, as well as inconsistent production in childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) [13, 14]. Inconsistent productions and approximations of speech sounds are unreliably captured in perceptual judgement of speech due to the categorical nature of perception [15]. For the purpose of this review, we will not include studies of SSDs arising from linguistically-based phonological issues. The primary focus, instead, is on phonetic-based articulation disorders arising from fine speech motor control issues, which include CAS, dysarthria and motor-speech disorders not otherwise specified [MSD-NOS; 13]. Children with these diagnoses are at increased risk for academic, social and emotional difficulties, and thus it is essential to monitor their speech performance during and subsequent to intervention, in order to assess intervention effectiveness [e.g. see 16].

To date, there has been no comprehensive and critical examination of methodology relating to outcome measures in children with SSD and speech motor control issues. There is one review of literature published between 1990 and 2006 relating to standardized speech/non-speech motor performance tests in children [1] and a handful of individual reviews of standardized tests in this area [17, 18]. To address this lack of summary information, we carried out a narrative review of the literature (between 1985 and 2014) that examined the use of measures of treatment change beyond standardized assessments. The purpose of this review was to evaluate the use of outcome measures to assess treatment change in children with SSD with a motor basis.

Method

Search Methodology

Seven databases were searched for journal articles published between January 1st, 1985 and December 31st, 2014 to identify intervention studies in children with SSD, including AMED, CINAHL, Embase, Medline (including In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations), PsycINFO, Scopus and speechBITE. A preliminary search revealed that studies reporting motor speech treatment were first published in mid-1980; therefore, 1985 was selected as the start-date for the search. Search terms relating to SSD were combined with terms relating to intervention. Specific keywords, syntax and refinements varied depending on database search criteria and limits. The results were further narrowed using the age search limit: child (0–18 years). The search strategy used in Medline is shown in Table 1. The completed search identified a total of 4029 articles.

Screening

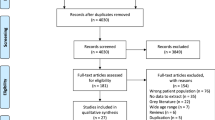

Figure 1 illustrates the screening process. All references were exported to RefWorks (Version 2.0; RefWorks-Cos). Duplicate records were removed and references were screened by title and abstract. Abstracts were included if they measured treatment of developmental SSDs with a motor basis. Abstracts describing treatment in children with phonologically-based SSD were only included if the treatment studied was an articulation-based intervention. Exclusion criteria included review articles, non-peer reviewed sources, test validity papers, assessment/diagnostic papers, no treatment administration/measurement studies, non-speech papers (e.g. hip dysplasia), language impairment, bilingualism, prosody/lexical deficits, phonological (linguistic-based) disorders, non-speech oro-motor exercises, alternative and augmentative communication (AAC), oral structural issues, traumatic brain injury/tumors, surgical-based intervention and publications not in English. Articles were not rated for quality and/or levels of evidence (e.g. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine–Levels of Evidence) [19] as the focus of the review was to examine the outcome measures used and not the efficacy of interventions reported. Two hundred and fifty articles were randomly selected and screened for acceptance by a second author. Krippendorf’s alpha for reliability between two independent coders was 0.85. Sixty-six articles were accepted for further analysis.

Results

Publication Year and Methodological Characteristics

Publication Year

The review identified 66 published studies (see Appendix Table 3) that report outcome measures following treatment in children with SSD with a motor basis. The number of studies per year has varied over the last three decades, with a surge in publications in recent years (see Fig. 2).

Participants

Table 2 shows the number of participants by speech disorder and the number of studies evaluating treatment in these populations included in the review. With few exceptions, the majority of studies included less than 10 participants (81.8 %). The age of participants ranged from 3; 0 to 16; 0 years.

Levels of Measurement

Figure 3 shows the types of measures used according to the classification outlined in the ICF-CY [4]. The outcome measures in the review relate to two of the ICF-CY categories: impairment level (body function) and participation level. Body function measures included perceptual, physiologic and acoustic measures (e.g. rating scales, transcription measures, tongue-palate contact patterns and formant frequencies). The majority of studies (68.2 %) use only perceptual measures to document change following treatment. About 25.8 % of studies use instrumental (acoustic and physiological measures). Only three studies (4.5 %) used participation level measures, ranging from a parent/school questionnaire to standardized assessment, such as Focus on the Outcomes of Children Under Six (FOCUS) and The Socialization Scale (from the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales–Second Edition) [7, 85••, 86]. See Appendix Table 4 for a detailed record of outcome measures used in the selected studies.

Discussion

This article provided a narrative review of studies reporting on outcome measures in treatment of children with motor-based SSDs. The review examined 66 treatment studies published between 1985 and 2014 (see Appendix Table 3) and summarized the publication year and methodological information from these studies. In the past 10 years, there has been a steady increase in publications under the scope of this review. Fifty-two different outcome measures (see Appendix Table 4) were identified, which were categorized into body function (perceptual and instrumental) and participation level measures. The range of available measures combined with limited information relating to the appropriate use of these measures makes it challenging for clinicians and researchers to accurately measure change following treatment in this population. A synthesis of the findings is discussed below in addition to recommendations for future clinical and research application.

The participants in the reviewed studies ranged in age, type and severity of speech disorder. Half of the studies included in the review evaluated treatment in children with an articulation disorder. The remaining studies included children with a phonological disorder, mixed articulation and phonological disorder, CAS or speech disorder secondary to other disorders. The majority of studies involved a small number of participants (n < 10), while one large-scale study (n = 730) examined outcomes of treatment of a whole speech and language therapy service cohort over a 12-year period [24]. The results highlight a need for larger-scale studies to ensure the generalizability of study findings.

Levels of Measurement

All papers in the review presented outcome measures at the ICF-CY body function level (body structure issues, such as oral structural issues, were excluded from analysis) (Fig. 3). The primary focus across studies was therefore impairment-based as studies aimed to increase accuracy of target sound productions, expand phonetic/phonemic inventories, decrease production variability and increase speech intelligibility.

Since the introduction of the ICF-CY in 2007, only three studies [32, 59, 65] measured outcomes from a broader social perspective, indicating that the application of the multiple levels in the ICF-CY framework in practice has not taken flight in the area of motor-based SSDs. Although the Mecrow et al.’s study [59] showed some significant and positive changes relating to how much the child’s speech difficulties affected him/her at home and at school, the study was not without limitations. They had a limited study design (e.g. control group did not complete the questionnaires), lack of information regarding tool validity and reliability, as well as reduced sensitivity of the questionnaire items. Pennington et al. [65] used FOCUS, a standardized tool, to examine communicative participation in young children with CP post-intensive therapy. Even though FOCUS scores increased following therapy (mean change scores; 30.3 for parents and 28.25 for teachers), these changes did not correlate with increases in intelligibility [65]. Another standardized, norm-reference measure—The Socialization Scale (from the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales–Second Edition)—was used to assess activity and participation levels following PROMPT treatment for children with CAS [32]. Increase in scores post treatment was significant for three out of four participants based on confidence intervals provided in the test manual. The finding of limited reporting of treatment change at the level of activity and participation is not dissimilar to those reported in the recent review by Baker and McLeod [8] for studies on phonological intervention in children. In their review, the majority of 134 studies also evaluated change in treatment only at the impairment level [8].

The lack of participation level measures is surprising, since after the late 1990s (1996–1997) at least three outcome measures were developed that focus on measuring change from a broader social perspective and could be used with pre-school children with speech and language disorders. These measures are American-Speech-Language-Hearing Association National Outcome Measure System (Pre-K NOMS), Therapy Outcome Measures (TOMs) and FOCUS [7, 85••, 88, 89]. Of these three measures, FOCUS is particularly recommended due to its sensitivity, published data on validity and reliability and its ability to capture changes across all of the ICF-CY levels [7, 85••]. In a recent study, the FOCUS measure was also shown to be sensitive to intensity of motor speech treatment in children with CAS, with larger effect sizes reported for higher (twice/week) than lower (once/week) intensity of treatment [90•]. In sum, both clinicians and researchers are strongly encouraged to adopt a more comprehensive intervention measurement and reporting strategy across all ICF-CY levels. A comprehensive review of assessment and intervention procedures as they relate to ICF-CY levels can be found in McLeod and Threats [10].

Transcription-Based Perceptual Procedures

Outcome measures using transcription-based approaches were very common across the reviewed articles (84.8 %). These measures include standardized tests, criterion-referenced measures and measures of intelligibility. Transcription measures were used across a range of speaking tasks from imitation to spontaneous speech at word, sentence and conversation level. In the reviewed studies, clinicians either used broad “phonemic” transcriptions (21.2 %, e.g. Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation-2 [GFTA-2; [91]) or narrow “phonetic” transcriptions (18.2 %, e.g. Khan-Lewis Phonological Analysis-2 [KLPA-2; [92]), while the remainder of studies does not specify the type of transcription employed. As a perceptual procedure, however, transcription is susceptible to bias and error. For example, listeners may “fill in” information from the acoustic signal, a phenomenon known as phonemic restoration; listeners’ perception is influenced by stress and intonation patterns; and even expert judges have poor inter-rater reliability [15]. While narrow transcription provides greater level of detail, it is less reliable than broad transcription [15]. Additionally, the finer discrimination required to describe distortions in motor-based speech disorders is limited due to the categorical nature of auditory perception [15].

Standardized Norm-Referenced Tests

Standardized assessments (e.g. norm-referenced) were used in 19.7 % studies. As a general rule, the use of norm-referenced standardized tests to measure change following treatment is not recommended due to serious limitations such as, regression to mean (i.e. participants with low scores at pretest may improve more than those with high scores) and lack of sensitivity. Norm-referenced tests may sample a wide range of behaviours and those targeted in intervention may only be a subset of these behaviours, and therefore, the test may not be sensitive enough to document behavioural change following treatment [93]. Thus, use of norm-referenced tests may result in under or overestimation of change [for excellent reviews on this topic, see 1, 93, 94].

One way to remediate these problems is to utilize norm-referenced tests in a criterion referenced-mode for assessing treatment progress. For example, Namasivayam et al. [62••] used pre–post scores from the GFTA-2 to investigate the effect of PROMPT therapy on speech production and intelligibility in children with moderate to severe SSD. They relied on the standard error of measurement (SEM) to determine significant change following treatment that is not a result of measurement error. The mean SEM for all pre-school age groups in the GFTA-2 is 3.7 and 3.0 for males and females, respectively [91]. Therefore, a minimum increase of 4-points was required at post testing to indicate meaningful improvement in articulation skills.

Criterion-Referenced Procedures

Given the above difficulties using norm-referenced standardized tests, it is not surprising that researchers and clinicians most often use criterion-based scoring to assess intervention-related change in SSDs [94]. Our analysis reveal that the majority (68.2 %) have utilized criterion referenced procedures (e.g. Percent consonant correct (PCC), percent vowel correct (PVC) and accuracy of target sounds) alone, or, in fewer instances, in combination with objective instrumental measures (25.8 %). Although transcription-based criterion-referenced procedures like PCC [e.g. 95] are better than using norm-referenced tests, they are not without limitations. First, PCC was originally designed to assess severity (in bands, e.g. 50–65 % = moderate-severe) rather than measure change subsequent to intervention [96]. Second, the original calculation of PCC required measuring all consonants in all word positions—treatment of select phonemes/sounds did not significantly alter PCC scores. Several modifications to PCC have been made, such as using pre-determined subsets of sounds, or using a differential weighting approach (PCC-Revised) [48, 97]. These changes, however, still do not permit scoring of closer approximations within omitted or substituted sound categories [96].

The limitations with PCC-type measures have led to alternative procedures like the probe-word scoring system (PSS; 96] that allow monitoring of “degrees of change” or approximations towards specific therapy targets. Early PSS systems (e.g. those used by Hall et al.) [96] utilized a voice, place,and manner judgements, where a minus point is given for each feature mismatch to the target. More recent versions of PSS are more sophisticated and use a 3-point scaled perceptual scoring (0 = incorrect production, 1 = close approximation and 2 = correct production) that includes both segmental and suprasegmental aspects of words and phrases [e.g. 32, 63, 72, 75, 76, 98••]. These newer PSS methods are a substantial departure from earlier auditory-perceptual scoring of distinctive feature errors as they include visual observation and reporting of movement gesture approximations [e.g. 32, 72] as well as sound distortions, and temporal and prosodic aspects of speech productions [98••].

Nevertheless, PSS methods do not account for changes in articulatory/sound transitions, changes in movement trajectories, subtle changes in speech motor control, vowel productions or suprasegmentals, which may affect overall speech intelligibility scores [51, 62••, 99]. Further, speech intelligibility at both the word-and sentence-level was significantly correlated with speech motor control (measured using Verbal Motor Production assessment for Children (VMPAC) [100] and not articulatory proficiency (measured using GFTA-2) [62••, 91].

Speech Intelligibility

Only a few studies (19.7 %) reviewed in this manuscript report changes in overall speech intelligibility as a treatment outcome measure, despite this being an important goal of speech therapy in general [33, 51, 101, 102]. Intelligibility is a measure of severity of speech impairment [103] and an index of body function in the ICF-CY [10, 104]. Speech samples in the reviewed studies ranged from spontaneous speech elicited during naturalistic play to word/sentence imitation or picture naming tasks. In children with severe SSDs and unintelligible speech, eliciting sufficient spontaneous speech in a naturalistic setting may not be possible as it may be difficult to quantify listener understanding when target words are not known. Thus, elicited procedures such as imitation or picture-naming were more frequently used with these children [51, 71, 105].

The speech intelligibility assessment procedures typically involved either the listener selecting a word from multiple alternatives (closed-set; e.g. Children’s Speech Intelligibility Measure (CSIM)) [106] or writing down what they hear (open-set; e.g. Beginner’s Intelligibility Test (BIT)) [107]. Impressionistic judgements and rating scales, given their reported lack of sensitivity, validity and reliability, were rarely reported in research studies reviewed here. Nevertheless, these measures are popular with clinicians, as indicated in a recent survey [71, 108]. Overall findings from the current study are not dissimilar to those reported by others for children with phonologically-based SSD, as shown in a recent review of outcome measures for children with phonologically-based SSD, where only 2 of 134 studies made reference to an intelligibility assessment [8].

Another area of speech intelligibility testing that requires further attention is the need for a behavioural standard to indicate that observed changes in speech intelligibility following treatment are not due to measurement error. Namasivayam et al. [62••] indicated that ∼8 % change in CSIM word-level speech intelligibility scores following motor speech treatment was outside of 90 % confidence intervals (see CSIM test manual) [104] indicating an actual change in child’s performance outside of measurement error. Of course, such behavioural standards are influenced by type of elicitation procedures, type of treatment and nature and severity of SSD; having such cut-off scores, however, will be one step closer to facilitating the integration of more robust and valid speech intelligibility testing procedures in the clinic.

Instrumental Procedures

In the reviewed studies, only a small percentage (30.3 %) has utilized instrumental analysis to evaluate change following treatment. Instrumental procedures were most frequently used in studies providing instrumentation-based treatment including electropalatography (EPG), ultrasound and motion-tracking systems such as Vicon 460 (Vicon Motion Systems, LA, USA). It is argued that in order to interact optimally with instruments and receive maximum benefits children must be at certain maturity and cognitive development; hence children under the age of 5 years are considered poor candidates. Further, due to the high cost of devices and their parts (e.g. a custom artificial palate for EPG), the use of instruments has been restricted to children with severe articulation disorders for whom conventional treatments have failed [52].

In the reviewed studies, instrumentation was used to objectively document pre–post changes [e.g. 29, 36, 38], and continuously track intervention-related changes [43]. EPG measures are concerned with a proper tongue position and closure interval duration during consonant production [e.g. 29, 36, 38, 43, 64]. Articulatory kinematic variables reported in two studies using the Vicon motion-tracking system included displacements, peak velocities and durations of movements of the lips and jaw [40, 79•]. These studies reported that changes in articulatory kinematics were associated with positive changes in PCC/PVC scores and visual improvements in speech movement accuracy and speech intelligibility following intervention. The instruments do not have to be very sophisticated or expensive. The importance of using accessible and available acoustic measures is highlighted in the study by Huer [43]. Huer tracked intervention over a 70-day period for a child with /w/ → /r/ substitution using both spectrographic analysis (e.g. second formant transition rates, standard deviation of formant values) and perceptual (percent correct) approaches. Changes in acoustic-spectrographic measures were present earlier than changes in perceptual judgement and thus offered greater precision in measuring speech production change over the course of intervention. These findings highlight the importance of using instruments to track results of response evocation strategy across time in order to modify treatment online as necessary. Considering the significant limitations of perceptual measures, we must move toward consistently using instrumentation to evaluate change during and following treatment.

Application to Practice

The importance of aligning theory, disorder classification and measurement cannot be over-emphasized [109] and is key to understanding mechanism of treatment action. Treatment and measurement strategy should be aligned with underlying deficits. For example, if children with CAS have difficulty in planning and/or programming speech movements, then effective treatment and measures of treatment change should be focused on these components [55]. To illustrate, Pennington et al. [110] implemented a speech breathing and speaking rate treatment to support articulatory precision with six children with cerebral palsy. They chose to use speech intelligibility as their only measure of treatment change. Although these strategies improve speech intelligibility as a whole, as Pennington et al. [110] pointed out without direct measures of change in speech breathing and articulation we cannot decipher factors that contributed to changes in speech intelligibility. Clinicians and researchers should routinely create a tentative hypothesis of why an intervention is expected to work, i.e. a possible mechanism of therapeutic action or effect and then proceed to choose an outcome measure that best reflects this hypothesis.

Clinically, measurement of treatment change should not be restricted to posttreatment outcome measures. Ongoing measurement could guide decisions at every step of the clinical process [111]. The use of ongoing probes that assess multi-dimensional aspects of speech (e.g. movement trajectories and prosody) can be useful to guide treatment goals [32, 43, 72, 112]. The accurate evaluation of change during treatment will help clinician’s to respond efficiently to the specific needs of a child and adjust treatment targets to optimise treatment effectiveness.

The majority of studies in the review focus on measuring specific aspects of speech, without taking into account the whole child and how they use speech to interact with their environment. As highlighted by Baker and McLeod [9], the ICF-CY framework provides a scaffold to think about the child from a broader perspective. Changes at the level of body function must also have an impact at the level of participation in order to determine that treatment is effective and functional to meet a child’s needs.

Conclusion

The narrative review identified a wide variation of measures used to document change following treatment in children with SSD with a motor basis. It is critical to first understand the nature of the underlying deficit before choosing a specific outcome measure [109]. Clinicians and researchers need to be aware of and address the limitations of perceptual measurement, for example, by using reference samples and reducing sources of variability [15]. Additionally, perceptual measures should be supplemented with instrumental measures of the same behaviours to increase reliability and precision of analysis [15]. Further studies using multiple levels of measurement (perceptual/ instrumental and body function/participation) will strengthen our understanding of the relationship between measures and evaluate the functional, meaningful impact treatment has on children with motor-based SSD.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

McCauley RJ, Strand EA. A review of standardized tests of nonverbal oral and speech motor performance in children. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 2008;17:81–91.

American Speech-Language Hearing Association. Scope of practice in speech-language pathology. 2007. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/policy/SP2007-00283/. Accessed 1 Mar 2015.

Olswang LB, Bain B. Data collection monitoring children’s treatment progress. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 1994;3(3):55–66.

World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability, and health: Children & youth version: ICF-CY. Geneva: WHO Press; 2007.

McLeod S. Speech pathologists’ application of the ICF to children with speech impairment. Int J Speech-Lang Pa. 2004;6(1):75–81.

McLeod S, McCormack J. Application of the ICF and ICF-children and youth in children with speech impairment. Semin Speech Lang. 2007;28(4):254–64.

Thomas-Stonell N, Oddson B, Robertson B, Rosenbaum P. Predicted and observed outcomes in preschool children following speech and language treatment: Parent and clinician perspectives. J Commun Disord. 2009;42(1):29–42.

Baker E, McLeod S. Evidence-based practice for children with speech sound disorders: part 1 narrative review. Lang Speech Hear Ser. 2011;42(2):102–39.

Baker E, McLeod S. Evidence-based practice for children with speech sound disorders: part 2 application to clinical practice. Lang Speech Hear Ser. 2011;42(2):140–51.

McLeod S, Threats TT. The ICF-CY and children with communication disabilities. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2008;10(1–2):92–109.

Yaruss J. Application of the ICF in fluency disorders. Semin Speech Lang. 2007;28:312–22.

Washington KN. Using the ICF within speech-language pathology: Application to developmental language impairment. Adv Speech-Lang Pathol. 2007;9:242–55.

Shriberg LD, Fourakis M, Hall SD, Karlsson HB, Lohmeier HL, McSweeny JL, et al. Extensions to the speech disorders classification system (SDCS). Clin Linguist Phonet. 2010;24(10):795–824.

Dodd B, McCormack P. A model of speech processing for differential diagnosis of phonological disorders. In: Dodd B, editor. Differential diagnosis of children with speech disorders. London: Whurr; 1995. p. 65–89.

Kent RD. Hearing and believing: some limits to the auditory-perceptual assessment of speech and voice disorders. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 1996;5(3):7–23.

Raitano NA, Pennington BF, Tunick RA, Boada R, Shriberg LD. Pre-literacy skills of subgroups of children with speech sound disorders. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2004;45:821–35.

Guyette TW. Review of the apraxia profile. In: Plake BS, Impara PC, editors. The fourteenth mental measurements yearbook. Lincoln: Buros Institute of Mental Measurements; 2001. p. 57–8.

Towne RL. Review of the oral speech mechanism screening examination. In: Plake BS, Impara JC, editors. The fourteenth mental measurements yearbook. 3rd ed. Lincoln: Buros Institute of Mental Measurements; 2001. p. 868–9.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, Greenhalgh T, Heneghan C, Liberati A, et al. The 2011 Oxford CEBM Evidence Levels of Evidence (Introductory Document). Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Retrieved from http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653. Accessed 27 Mar 2015.

Adler-Bock M, Bernhardt B, Gick B, Bacsfalvi P. The use of ultrasound in remediation of North American English /r/ in 2 adolescents. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 2007;16(2):128–39.

Ballard KJ, Robin DA, McCabe P, McDonald J. A treatment for dysprosody in childhood Apraxia of speech. J Speech Lang Hear R. 2010;53:1227–45.

Bernhardt MB, Bacsfalvi P, Adler-Bock M, Shimizu R, Cheney A, Giesbrecht N, et al. Ultrasound as visual feedback in speech habilitation: Exploring consultative use in rural British Columbia. Canada Clin Linguist Phonet. 2008;22(2):149–62.

Boliek CA, Fox CM. Individual and environmental contributions to treatment outcomes following a neuro- plasticity-principled speech treatment (LSVT LOUD) in children with dysarthria secondary to Cerebral Palsy. Int J Speech-Lang Pa. 2014;16(4):372–85.

Broomfield J, Dodd B. Is speech and language therapy effective for children with primary speech and language impairment? Report of a randomized control trial. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2011;46(6):628–40.

Byun TM, Hitchcock ER. Investigating the use of traditional and spectral biofeedback approaches to intervention for/r/misarticulation. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 2012;21(3):207–21. This paper is of major importance as it shows that changes evaluated through instrumental methods are successful in addressing persistent speech errors.

Camarata SM. The application of naturalistic conversation training to speech production in children with speech disabilities. J Appl Behav Anal. 1993;26(2):173–82.

Camarata S, Yoder PP, Camarata MM. Simultaneous treatment of grammatical and speech- comprehensibility deficits in children with Down syndrome. Downs Syndr Res Pract. 2006;11(1):9–17.

Carter P, Edwards S. EPG therapy for children with long-standing speech disorders: predictions and outcomes. Clin Linguist Phonet. 2004;18(6–8):359–72.

Cleland J, Timmins C, Wood SE, Hardcastle WJ, Wishart JG. Electropalatographic therapy for children and young people with Down’s syndrome. Clin Linguist Phonet. 2009;23(12):926–39.

Crosbie S, Holm A, Dodd B. Intervention for children with severe speech disorder: a comparison of two approaches. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2005;40(4):467–91.

Cummings AE, Barlow JA. A comparison of word lexicality in the treatment of speech sound disorders. Clin Linguist Phonet. 2011;25(4):265–86.

Dale PS, Hayden DA. Treating speech subsystems in childhood apraxia of speech with tactual input: the PROMPT approach. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 2013;22(4):644–61.

Dodd B, Bradford A. A comparison of three therapy methods for children with different types of developmental phonological disorder. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2000;35(2):189–209.

Edeal DM, Gildersleeve-Neumann CE. The importance of production frequency in therapy for childhood apraxia of speech. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 2011;20(2):95–110.

Forrest K, Elbert M, Dinnsen DA. The effect of substitution patterns on phonological treatment outcomes. Clin Linguist Phonet. 2000;14(7):519–31.

Gibbon FE, McNeill AM, Wood SE, Watson JM. Changes in linguapalatal contact patterns during therapy for velar fronting in a 10‐year‐old with Down’s syndrome. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2003;38(1):47–64.

Gibbon F, Stewart F, Hardcastle WJ, Crampin L. Widening access to electropalatography for children with persistent sound system disorders. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 1999;8:319–34.

Gibbon FE, Wood SE. Using electropalatography (EPG) to diagnose and treat articulation disorders associated with mild cerebral palsy: a case study. Clin Linguist Phonet. 2003;17(4–5):365–74.

Gierut JA, Champion AH. Interacting error patterns and their resistance to treatment. ClinLinguist Phonet. 1999;13(6):421–31.

Grigos MI, Hayden D, Eigen J. Perceptual and articulatory changes in speech production following PROMPT treatment. J Med Speech-Lang Pa. 2010;18(4):46.

Günther T, Hautvast S. Addition of contingency management to increase home practice in young children with a speech sound disorder. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2010;45(3):345–53.

Holm A, Ozanne A, Dodd B. Efficacy of intervention for a bilingual child making articulation and phonological errors. Int J Biling. 1997;1(1):55–69.

Huer MB. Acoustic tracking of articulation errors [r]. J Speech Hear Disord. 1989;54(4):530–4.

Iuzzini J, Forrest K. Evaluation of a combined treatment approach for childhood apraxia of speech. Clin Linguist Phonet. 2010;24(4–5):335–45.

Kadis DS, Goshulak D, Namasivayam AK, Pukonen M, Kroll R, Luc F, et al. Cortical thickness in children receiving intensive therapy for idiopathic apraxia of speech. Brain Topogr. 2014;27(2):240–7. This paper is of importance as it is the first article that shows cortical changes in children with CAS following speech therapy.

Klein ES. Phonological/traditional approaches to articulation therapy: a retrospective group comparison. Lang Speech Hear Ser. 1996;27(4):314–23.

Koegel RL, Koegel LK, Ingham JC, Van Voy K. Within-clinic versus outside-of-clinic self-monitoring of articulation to promote generalization. J Speech Hear Disord. 1988;53(4):392–9.

Lagasse B. Evaluation of melodic intonation therapy for developmental apraxia of speech. Music Ther Perspect. 2012;30(1):49–55.

Lousada M, Jesus LM, Capelas S, Margaça C, Simões D, Valent A, et al. Phonological and articulation treatment approaches in Portuguese children with speech and language impairments: a randomized controlled intervention study. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2013;48(2):172–87.

Mendes AM, Afonso E, Lousada M, Andrade F. Teste fonético-fonológico ALPE. Aveiro: Designeed; 2009.

Lousada M, Jesus MT, Hall A, Joffe V. Intelligibility as a clinical outcome measure following intervention with children with phonologically based speech-sound disorders. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2014;49(5):584–601.

Lundeborg I, McAllister A. Treatment with a combination of intra-oral sensory stimulation and electropalatography in a child with severe developmental dyspraxia. Logop Phonatr Voco. 2007;32(2):71–9.

Maas E, Farinella KA. Random versus blocked practice in treatment for childhood apraxia of speech. J Speech Lang Hear R. 2012;55(2):561–78.

Marchant J, McAuliffe MJ, Huckabee ML. Treatment of articulatory impairment in a child with spastic dysarthria associated with cerebral palsy. Dev Neurorehabil. 2008;11(1):81–90.

Martikainen AL, Korpilahti P. Intervention for childhood apraxia of speech: a single-case study. Child Lang Teach. 2011;27(1):9–20.

McAuliffe MJ, Cornwell PL. Intervention for lateral /s/ using electropalatography (EPG) biofeedback and an intensive motor learning approach: a case report. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2008;43(2):219–29.

McCabe P, Macdonald-D’Silva AG, van Rees LJ, Ballard KJ, Arciuli J. Orthographically sensitive treatment for dysprosody in children with Childhood Apraxia of Speech using ReST intervention. Dev Neurorehabil. 2014;7(2):137–46.

McIntosh B, Dodd B. Evaluation of Core Vocabulary intervention for treatment of inconsistent phonological disorder: Three treatment case studies. Child Lang Teach. 2008;25(1):09–29.

Mecrow C, Beckwith J, Klee T. An exploratory trial of the effectiveness of an enhanced consultative approach to delivering speech and language intervention in schools. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2010;45(3):354–67.

Modha G, Bernhardt B, Church R, Bacsfalvi P. Case study using ultrasound to treat. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2008;43(3):323–9.

Mowrer DE, Conley D. Effect of peer administered consequences upon articulatory responses of speech-defective children. J Commun Disord. 1987;20(4):319–25.

Namasivayam AK, Pukonen M, Goshulak D, Yu VY, Kadis DS, Kroll R, et al. Relationship between speech motor control and speech intelligibility in children with speech sound disorders. J Commun Disord. 2013;46(3):264–80. This paper is of major importance as it demonstrates the relationship between different levels of measurement, that is speech motor control and speech intelligibility.

Namasivayam AK, Pukonen M, Hard J, Jahnke R, Kearney E, Kroll R, et al. Motor speech treatment protocol for developmental motor speech disorders. Dev Neurorehabil. 2013. doi:10.3109/17518423.2013.832431.

Nordberg A, Carlsson G, Lohmander A. Electropalatography in the description and treatment of speech disorders in five children with cerebral palsy. Clin Linguist Phonet. 2011;25(10):831–52.

Pennington L, Roelant E, Thompson V, Robson S, Steen N, Miller S. Intensive dysarthria therapy for younger children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:464–71.

Preston JL, Brick N, Landi N. Ultrasound biofeedback treatment for persisting childhood apraxia of speech. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 2013;22(4):627–43.

Preston JL, McCabe P, Rivera-Campos A, Whittle JL, Landry E, Maas E. Ultrasound visual feedback treatment and practice variability for residual speech sound errors. J Speech Lang Hear R. 2014;57(6):2102–2115.

Flipsen Jr P, Sacks S, Neils-Strunjas J. Effectiveness of systematic articulation training program accessing computers (SATPAC) approach to remediate dentalized and interdental /s, z/: a preliminary study. Percept Mot Skills. 2013;117(2):559–77.

Shawker TH, Sonies BC. Ultrasound biofeedback for speech training. Instrumentation and preliminary results. Invest Radiol. 1985;20(1):90–3.

Skelton SL, Hagopian AL. Using randomized variable practice in the treatment of childhood apraxia of speech. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 2014;23(4):599–611.

Speake J, Stackhouse J, Pascoe M. Vowel targeted intervention for children with persisting speech difficulties: Impact on intelligibility. Child Lang Teach. 2012;28(3):277–95.

Square PA, Namasivayam AK, Bose A, Goshulak D, Hayden D. Multi‐sensory treatment for children with developmental motor speech disorders. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2014;49(5):527–42.

Stokes SF, Ciocca V. The substitution of [s] for aspirated targets: perceptual and acoustic evidence from Cantonese. Clin Linguist Phonet. 1999;13(3):183–97.

Stokes SF, Griffiths R. The use of facilitative vowel contexts in the treatment of post‐alveolar fronting: a case study. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2010;45(3):368–80.

Strand EA, Debertine P. The efficacy of integral stimulation intervention with developmental apraxia of speech. J Med Speech-Lang Pa. 2000;8(4):295–300.

Strand EA, Stoeckel R, Baas B. Treatment of severe childhood apraxia of speech: a treatment efficacy study. J Med Speech-Lang Pa. 2006;14(4):297–307.

Thomas DC, McCabe P, Ballard K. Rapid syllable transitions (ReST) treatment for childhood apraxia of speech: the effect of lower dose-frequency. J Commun Disord. 2014;51:29–42. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2014.06.004.

Tung LC, Lin CK, Hsieh CL, Chen CC, Huang CT, Wang CH. Sensory integration dysfunction affects efficacy of speech therapy on children with functional articulation disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:87.

Ward R, Strauss G, Leitão S. Kinematic changes in jaw and lip control of children with cerebral palsy following participation in a motor-speech (PROMPT) intervention. Int J Speech-Lang Pa. 2013;15(2):136–55. This paper is of importance as it shows that changes evaluated through instrumental methods (speech kinematic) are associated with positive changes in speech intelligibility.

Ward R, Leitão S, Strauss G. An evaluation of the effectiveness of PROMPT therapy in improving speech production accuracy in six children with cerebral palsy. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2014;16(4):355–71.

Weaver-Spurlock S, Brasseur J. The effects of simultaneous sound-position training on the generalization of [s]. Lang Speech Hear Ser. 1988;19(3):259–71.

Wood S, Wishart J, Hardcastle W, Cleland J, Timmins C. The use of electropalatography (EPG) in the assessment and treatment of motor speech disorders in children with Down's syndrome: evidence from two case studies. Dev Neurorehabil. 2009;12(2):66–75.

Wu PY, Jeng JY. Efficacy comparison between two articulatory intervention approaches for dysarthric cerebral palsy (CP) children. Asia Pacific Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing. 2004;9(1):28–32.

Yu VY, Kadis DS, Oh A, Gosulak D, Namasivayam A, Pukonen M, et al. Changes in voice onset time and motor speech skills in children following motor speech therapy: Evidence from/pa/productions. Clin Linguist Phonet. 2014;28(6):396–412.

Thomas‐Stonell N, Washington K, Oddson B, Robertson B, Rosenbaum P. Measuring communicative participation using the FOCUS©: focus on the outcomes of communication under six. Child Care Hlth Dev. 2013;39(4):474–80. This paper is of major importance as it validates the use of FOCUS, a participation level measure, for use with children with speech impairment, language impairment, and both speech and language impairment.

Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland adaptive behavior scales. 2nd ed. Circle Pines: AGS; 1984.

Dodd B. Children with speech disorder: defining the problem. In: Dodd B, editor. Differential diagnosis and treatment of children with speech disorder. London: Whurr; 2005. p. 3–23.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). National Outcome Measurement System (NOMS) for Speech–Language Pathology. 1996. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/NOMS/. Accessed 10 Mar 2015.

Enderby P, John A. Therapy outcome measures: speech-language pathology technical manual. London: Singular; 1997.

Namasivayam AK, Pukonen M, Goshulak D, Hard J, Rudzicz F, Rietveld T, et al. Treatment intensity and childhood apraxia of speech. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2015. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12154. This paper is of importance as it is one of the first studies to include measures of articulation, speech intelligibility and functional outcomes (i.e. body function and participation level measures) in the treatment of CAS population.

Goldman R, Fristoe M. Goldman fristoe test of articulation. 2nd ed. San Antonio: Pearson; 2000.

Khan L, Lewis N. Khan-Lewis phonological analysis. 2nd ed. San Antonio: Pearson; 2002.

McCauley RJ, Swisher L. Use and misuse of norm-referenced test in clinical assessment: a hypothetical case. J Speech Hear Disord. 1984;49(4):338–48.

McCauley RJ. Familiar strangers: criterion-referenced measures in communication disorders. Lang Speech Hear Ser. 1996;27:122–31.

Shriberg LD, Kwiatkowski J. Phonological disorders III: a procedure for assessing severity of involvement. J Speech Hear Disord. 1982;47:256–70.

Hall R, Adams C, Hesketh A, Nightingale K. The measurement of intervention effects in developmental phonological disorders. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 1998;33(S1):445–50.

Shriberg LD, Austin D, Lewis BA, McSweeny JL, Wilson DL. The percentage of consonants correct (PCC) metric extensions and reliability data. J Speech Lang Hear Re. 1997;40(4):708–22.

Maas E, Butalla CE, Farinella KA. Feedback frequency in treatment for childhood apraxia of speech. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 2012;21(3):239–57. This paper is of major importance as it comprehensively covers the use of probe-word scoring system: scoring errors in both segmental and suprasegmental aspects of words and phrases.

Bowen C, Cupples L. PACT: Parents and children together in phonological therapy. Adv Speech Lang Pathol. 2006;8:282–92.

Hayden D, Square P. Verbal motor production assessment for children. San Antonio: Pearson Education; 1999.

Flipsen P. Speaker-listener familiarity: Parents as judges of delayed speech intelligibility. J Commun Disord. 1995;28(1):3–19.

Miller N. Measuring up to speech intelligibility. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2013;48(6):601–12.

Yorkston KM, Beukelman DR, Hakel M, Dorsey M. Speech intelligibility test for windows. Lincoln: Communication Disorders Software; 1996.

Ma EPM, Worrall L, Threats TT. Introduction: the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) in clinical practice. Semin Speech Lang. 2007;28(4):241–3.

Kwiatkowski J, Shriberg LD. Intelligibility assessment in developmental phonological disorders: Accuracy of caregiver gloss. J Speech Lang Hear R. 1992;35(5):1095–104.

Wilcox K, Morris S. Children’s speech intelligibility measure. San Antonio: Pearson; 1999.

Osberger MJ, Robbins AM, Todd SL, Riley AI. Speech intelligibility of children with cochlear implants. Volta Rev. 1994;96:169–80.

Skahen SM, Watson M, Lof GL. Speech-Language Pathologists’ assessment practices for children with suspected speech sound disorders: results of a national survey. Am J Speech-Lang Pat. 2007;16:246–59.

Bowen C. Children’s speech sound disorders. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

Pennington L, Smallman C, Farrier F. Intensive dysarthria therapy for older children with cerebral palsy: findings from six cases. Child Lang Teach. 2006;22(3):255–73.

McCauley R. Measurement as a dangerous activity. J Speech Lang Pathol Audiol. 1989;13:29–32.

Tyler AA. Durational analysis of stridency errors in children with phonological impairment. Clin Linguist Phonet. 1995;9(3):211–28.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Yunusova and Ms. Kearney report grants from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

E. Kearney, F. Granata, Y. Yunusova, P. van Lieshout, D. Hayden and A. Namasivayam declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Specific Language Impairment/Speech Sound Disorder

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kearney, E., Granata, F., Yunusova, Y. et al. Outcome Measures in Developmental Speech Sound Disorders with a Motor Basis. Curr Dev Disord Rep 2, 253–272 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-015-0058-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-015-0058-2