Abstract

Objective

There is substantial evidence that the use of opioids increases the risk of adverse outcomes such as delirium, but whether this risk differs between the various opioids remains controversial. In this systematic review, we evaluate and discuss possible differences in the risk of delirium from the use of various types of opioids in older patients.

Methods

We performed a search in MEDLINE by combining search terms on delirium and opioids. A specific search filter for use in geriatric medicine was used. Quality was scored according to the quality assessment for cohort studies of the Dutch Cochrane Institute.

Results

Six studies were included, all performed in surgical departments and all observational. No study was rated high quality, one was rated moderate quality, and five were rated low quality. Information about dose, route, and timing of administration of the opioid was frequently missing. Pain and other important risk factors of delirium were often not taken into account. Use of tramadol or meperidine was associated with an increased risk of delirium, whereas the use of morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, and codeine were not, when compared with no opioid. Meperidine was also associated with an increased risk of delirium compared with other opioids, whereas tramadol was not. The risk of delirium appeared to be lower with hydromorphone or fentanyl, compared with other opioids. Numbers used for comparisons were small.

Conclusion

Some data suggest that meperidine may lead to a higher perioperative risk for delirium; however, high-quality studies that compare different opioids are lacking. Further comparative research is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Opioids increase the risk of delirium in elderly patients. |

Although there are some indications that meperidine and tramadol increase the risk of delirium, there are no convincing data that the risk of delirium in elderly patients is different for the various types of opioids. |

The quality of existing research is limited; further comparative research is needed with accurate documentation of the timing and dose of opioids, valid daily measurements to diagnose delirium, and consideration of potential confounding factors for developing delirium. |

1 Introduction

Delirium is an acute confusional state and a serious neuropsychiatric complication. It occurs specifically among hospitalized vulnerable elderly patients who experience acute stressor factors, including infections, new medications, and/or environmental changes [1]. Ten to thirty percent of patients admitted to hospital develop delirium [2]. Delirium is associated with poor functional recovery [3] and leads to increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs [4, 5]. Furthermore, this condition can also be very stressful for the patient’s relatives.

It has been shown that patients with delirium have on average 5.2 predisposing factors and 3.0 precipitating factors [6]. A number of studies reveal medication, specifically opioids, as a precipitating factor [4, 7, 8]. An association was found between opioids and delirium in patients admitted to an intensive care unit [4] and with the use of opioids in general [8]. Pain is an important precipitating factor for delirium as well [9]. As opioids are frequently used for pain control in elderly patients, both over- and under-treatment may initiate delirium.

The etiology of delirium is usually multifactorial and not completely understood. It is assumed that inflammation plays an important role in the pathophysiology of delirium [10]. Drug-induced delirium is thought to be the result of overactivity of the dopaminergic system and underactivity of the cholinergic system [10]. In particular, drugs with more anticholinergic properties increase the risk of delirium [11]. Furthermore, conditions such as renal failure and inflammation may influence the metabolism and clearance of drugs.

The risk of delirium may differ among the various opioids as a result of their specific pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. For example, both meperidine and tramadol have metabolites with high anticholinergic properties [12,13,14], whereas the 3-glucuronide metabolites of both morphine and hydromorphone have been implicated in neuroexcitation [15].

Delirium risk may thus be influenced by the choice of type of opioid. To establish whether delirium risk differs between the various opioids, we performed a systematic review.

2 Methods

We performed a search in MEDLINE by combining search terms from relevant Cochrane reviews on delirium and opioids [1, 8, 16, 17]. The search was combined with a specific geriatric search filter and covered a period from 1946 to December 2014 [18]. The search strategy is added as supplemental data. We manually checked the reference lists of obtained systematic reviews for eligible articles. Selection was first performed on the title and abstract (LS) and second on the full text (LS and BvM). Included were studies written in English or Dutch, limited to randomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, and case-control studies in hospital, long-term, or palliative care, with delirium as the outcome measure. All types of opioids were included. Exclusion criteria were mean age of the study population below 60 years and opioid-dependent populations. Studies in which a morphine equivalent was used to describe the total dose of multiple or unknown types of opioids or in which the effect of opioids combined with other medications was analyzed (acetaminophen excepted) were excluded. The critical appraisal was performed by two authors (LS and VvdZ) independently by using the quality assessment for cohort studies from the Dutch Cochrane Institute [19]. The final assessment of the quality was reached through discussion. Each study was scored as high, moderate, or low quality. We extracted data on the study population, definition and incidence of delirium, opioid type, route of administration, dose, and timing. The odds ratio (OR), hazard ratio, or relative risk with 95% confidence interval (CI) of each opioid for delirium were collected as the outcome measure. We intended to pool data, depending on the heterogeneity of the studies.

3 Results

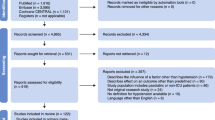

The primary search resulted in 966 articles; 924 were excluded based on the title and abstract (Fig. 1). After reading the full text of the remaining 42 articles and checking reference lists from relevant systematic reviews [8, 12], six studies were included [7, 9, 20,21,22,23]. Excluded studies discussed the effects of opioids in general, reported different types of opioids as morphine equivalents, used cognitive decline (without further specification) as the outcome measure, or reported a mean age of the study population below 60 years. The six included studies investigated eight different opioids: morphine, meperidine, fentanyl, tramadol, oxycodone, codeine, hydromorphone, and hydrocodone.

No study was rated as high quality, one study as moderate quality [9], and five studies were rated as low quality [7, 20,21,22,23]. Critical information was often missing, for example, dose, route and timing of administration of the opioid, and important confounders or risk factors for delirium were often not taken into account in the study design and analysis (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the study characteristics of the six included studies [7, 9, 20,21,22,23]. We included two retrospective cohort studies [22, 23], two prospective cohort studies [9, 20], and two nested case control studies [7, 21]. Two studies used a matched case-control design. One matched seven preoperative factors: age; poor cognitive function; poor physical function; alcohol abuse; markedly abnormal preoperative sodium, potassium or glucose levels; aortic aneurysm surgery, and non-cardiac thoracic surgery [7]. One matched age, type of surgery, and year of surgery [21].

All studies were performed in surgery departments. Two studies investigated one opioid compared with any other opioid and four studies compared specific opioids. The number of included patients per study ranged from 92 to 541. Five studies included patients with cognitive impairment. Delirium was diagnosed by the confusion assessment method in four studies, and in one study by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria. One study used a different delirium measure method: first, all inpatient charts were screened for delirium, confusion, disorientation, altered/change in mental status, metabolic encephalopathy, delusions, hallucinations, or visual-spatial distortions. Then, the patients who were identified through this screening were checked for the presence of delirium by their institution’s morbidity and mortality conference records.

Table 3 shows a summary of the study results. The route of administration was not reported in two of six studies and the dose of opioid was unknown in four of six studies. Timing and duration of the administration of the opioid differed between the studies and was not fully described in five of six studies.

Three studies found a significant risk of delirium from the use of meperidine, compared with other opioids (relative risk 2.4, 95% CI 1.3–4.5) [9], no opioid (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.3–5.5) [7], or morphine (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.15–4.17) [23]. The other three studies on different opioids showed the following results: increased risk of delirium of tramadol compared with no opioid (hazard ratio 7.1, 95% CI 2.2–22.5) [20], decreased risk from hydromorphone compared with other opioids (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.14–0.65) [21], and decreased risk from fentanyl compared with morphine (OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.07–0.69) [22]. Additionally, an interaction was found between morphine and oxycodone: morphine combined with oxycodone led to a significant increase in the risk of delirium [21].

Characteristics of the included studies, including definition of delirium, dose of opioid, and timing of administration, were not comparable and often not available. Because of this clinical heterogeneity and lack of information, a meta-analysis was not performed.

4 Discussion

In this systematic review, we aimed to investigate the difference in the risk of delirium from the use of various types of opioids in the elderly population. We found six studies that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria.

There seems to be an increased risk of delirium from the use of meperidine [7, 9, 23]. This risk is confirmed by a previous systematic review on the role of postoperative analgesia in delirium and cognitive decline that included three overlapping studies [12]. An increased risk of delirium owing to tramadol use was only shown in one study of low quality [20]; however, several case reports support this increased risk [24]. Despite the relative contraindication for tramadol use in older patients, based on this information, tramadol is still frequently prescribed in the Netherlands: there are 385,043 opioid users aged above 65 years, of whom 232,066 use tramadol or a combination of tramadol and paracetamol (60%) [25].

This review also suggests a protective effect of hydromorphone and fentanyl on delirium.

None of the included studies were randomized clinical trials and none were scored as high quality. Considering the low quality and small study population of the studies that report these effects, all of the above results should be interpreted with caution.

The low quality of five out of the six studies caused several limitations in the interpretation of the results. There was a big difference between sample size and the number of included patients, which led to a high risk of selection bias. The small study samples increase the risk of chance findings, especially in the studies in which several opioids or several medications were studied. Next, the definition of delirium, cognitive impairment, and co-morbidity varied for the different studies, which make comparisons between the studies near impossible. Details about opioid use, including route of administration, dose, and timing were often lacking. It has been shown that these are important details when studying the effect of opioids on delirium and these have to be documented accurately for good comparison between studies [26,27,28]. In addition, the studies were all observational in nature and several confounding factors were not taken into account, including pain level, cognitive impairment, and co-morbidities of the included patients [9, 28, 29]. Preoperative resting pain and the increase in pain level on the first day after surgery are both significant risk factors for postoperative delirium [28]. Neuropathic pain can activate microglia cells and thus lead to an inflammatory state that is associated with delirium [30]. Consequently, delirium as a result of pain, not as a result of opioid use, might play an important role in the included studies.

A major strength of our study is our comprehensive search, further enhanced by a specific search filter for use in geriatric medicine [18]. We have limited our inclusion to comparative research. If we had included case reports, we might have found more indications for tramadol or other opioids as precipitating factors for delirium.

5 Conclusion

There are no convincing data that the risk of delirium in elderly patients depends on the type of opioid. Studies performed to date were all observational and of low-to-moderate quality. There are some indications that meperidine increases the risk of delirium in elderly patients. Further comparative research is needed with accurate documentation of the timing and dose of opioids, valid daily measurements to diagnose delirium, and consideration of potential confounding factors for developing delirium.

References

Clegg A, Siddiqi N, Heaven A, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in older people in institutional longterm care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD009537.

Levkoff S, Cleary P, Liptzin B, Evans DA. Epidemiology of delirium: an overview of research issues and findings. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):149–67.

Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Michaels M, Resnick NM. Delirium is independently associated with poor functional recovery after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):618–24.

Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study of risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(8):1297–304.

Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, et al. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27–32.

Laurila JV, Laakkonen ML, Tilvis RS, Pitkala KH. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in a frail geriatric population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):249–54.

Marcantonio ER, Juarez G, Goldman L, et al. The relationship of postoperative delirium with psychoactive medications. JAMA. 1994;272(19):1518–22.

Clegg A, Young JB. Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40(1):23–9.

Morrison RS, Magaziner J, Gilbert M, et al. Relationship between pain and opioid analgesics on the development of delirium following hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(1):76–81.

MacLullich AMJ, Ferguson KJ, Miller T, et al. Unravelling the pathophysiology of delirium: a focus on the role of aberrant stress responses. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):229–38.

Van Gool WA, Van de Beek D, Eikelenboom P. Systemic infection and delirium: when cytokines and acetylcholine collide. Lancet. 2010;375(9716):773–5.

Fong HK, Sands LP, Leung JM. The role of postoperative analgesia in delirium and cognitive decline in elderly patients: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(4):1255–66.

Ghosh S, Mondal SK, Bhattacharya A, Saddichha S. Acute delirium due to parenteral tramadol. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:492685.

Eisendrath SJ, Goldman B, Douglas J, et al. Meperidine-induced delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144(8):1062–5.

Smith M. Neuroexcitatory effects of morphine and hydromorphone: evidence implicating the 3-glucuronide metabolites. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27(7):524–8.

Basurto Ona X, Comas DR, Urrútia G. Opioids for acute pancreatitis pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:79.

O’Neil CK, Hanlon JT, Marcum ZA. Adverse effects of analgesics commonly used by older adults with osteoarthritis: focus on non-opioid and opioid analgesics. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(6):331–42.

Van de Glind EM, Van Munster BC, Spijker R, et al. Search filters to identify geriatric medicine in Medline. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(3):468–72.

Scholten RJPM, Offringa M, Assendelft WJJ. Inleiding in evidence-based medicine. Klinisch handelen gebaseerd op bewijsmateriaal. Vierde herziene druk. Houten: Bohn, Stafleu, Van Loghum; 2013.

Brouquet A, Cudennec T, Benoist S, et al. Impaired mobility, ASA status and administration of tramadol are risk factors for postoperative delirium in patients aged 75 years or more after major abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):759–65.

Nandi S, Harvey WF, Saillant J, et al. Pharmacologic risk factors for post-operative delirium in total joint arthroplasty patients: a case-control study. J Arthroplasy. 2014;29(2):268–71.

Shiiba M, Takei M, Nakatsuru M, et al. Clinical observations of postoperative delirium after surgery for oral carcinoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38(6):661–5.

Adunsky A, Levy R, Heim M, et al. Meperidine analgesia and delirium in aged hip fracture patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35(3):253–9.

Rughooputh N, Griffiths R. Tramadol and delirium. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(5):632–3.

GIP/Zorginstituut Nederland. Aantal gebruikers naar leeftijd en geslacht voor ATC-subgroep N02: analgetica in 2015. Available from: https://www.gipdatabank.nl/databank.asp?tabel=03-lftgesl&geg=gebr&item=N02A. Accessed 7 Feb 2017.

Andrejaitiene J, Sirvinskas E. Early post-cardiac surgery delirium risk factors. Perfusion. 2012;27(2):105–12.

Burkhart CS, Dell-Kuster S, Gamberini M, et al. Modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;24(4):555–9.

Vaurio LE, Sands LP, Wang Y, et al. Postoperative delirium: the importance of pain and pain management. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(4):1267–73.

Szeto HH, Inturrisi CE, Houde R, et al. Accumulation of normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine, in patients with renal failure of cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86(6):738–41.

Guan Z, Kuhn JA, Wang X, et al. Injured sensory neuron-derived CSF1 induces microglial proliferation and DAP12-dependent pain. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(1):94–101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

Lieke M. Swart, Vera van der Zanden, Petra E. Spies, Sophia E. de Rooij and Barbara C. van Munster have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Swart, L.M., van der Zanden, V., Spies, P.E. et al. The Comparative Risk of Delirium with Different Opioids: A Systematic Review. Drugs Aging 34, 437–443 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0455-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0455-9