Abstract

Aims

Given the high prevalence of psychotropic medication use in people with dementia and the potential for different prescribing practices in men and women, our study aimed to investigate sex differences in psychotropic medication use in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) living in the US and Finland.

Methods

We used data collected between 2005 and 2011 as part of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) in the US, and Medication use and Alzheimer’s disease (MEDALZ) cohorts in Finland. We evaluated psychotropic medication use (antidepressant, antipsychotic, anxiolytic, sedative, or hypnotic) in participants aged 65 years or older. We employed multivariable logistic regression adjusted for demographics, co-morbidities, and other medications to estimate the magnitude of the association (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) according to sex.

Results

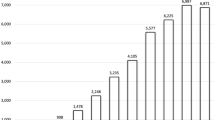

We included 1099 NACC participants (502 [45.68%] men, 597 [54.32%] women), and 67,049 participants from the MEDALZ cohort (22,961 [34.24%] men, 44,088 [65.75%] women). Women were more likely than men to use psychotropic medications: US, 46.2% vs. 33.1%, p < 0.001; Finland, 45.3% vs. 36.1%, p < 0.001; aOR was 2.06 (95% CI 1.58–2.70) in the US cohort and 1.38 (95% CI 1.33–1.43) in the Finnish cohort. Similarly, of the different psychotropic medications, women were more likely to use antidepressants (aOR-US: 2.16 [1.44–3.25], Finland: 1.52 [1.45–1.58]) and anxiolytics (aOR-US: 2.16 [1.83–3.96], Finland: 1.17 [1.13-1.23]) than men.

Conclusion

Older women with AD are more likely to use psychotropic medications than older men, regardless of study population and country. Approaches to mitigate psychotropic medication use need to consider different prescribing habits observed in older women vs. men with AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rattinger GB, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic management of dementia across settings of care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(5):723–33.

Gnjidic D, et al. Impact of high risk drug use on hospitalization and mortality in older people with and without Alzheimer’s disease: a national population cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e83224.

Vasudev A, et al. Trends in psychotropic dispensing among older adults with dementia living in long-term care facilities: 2004–2013. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(12):1259–69.

Ballard C, Waite J. The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD003476.

Banerjee S, et al. Sertraline or mirtazapine for depression in dementia (HTA-SADD): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):403–11.

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1934–43.

Gnjidic D, et al. Drug Burden Index associated with function in community dwelling older people living in Finland: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med. 2012;44:458–67.

Gnjidic D, et al. High risk prescribing and incidence of frailty among older community-dwelling men. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:521–8.

Legato MJ, Johnson PA, Manson JE. Consideration of sex differences in medicine to improve health care and patient outcomes. JAMA. 2016;316(18):1865–6.

Clayton JA, Tannenbaum C. Reporting sex, gender, or both in clinical research? JAMA. 2016;316(18):1863–4.

Bierman AS, et al. Sex differences in inappropriate prescribing among elderly veterans. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(2):147–61.

Johnell K, Weitoft GR, Fastbom J. Sex differences in inappropriate drug use: a register-based study of over 600,000 older people. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(7):1233–8.

Foebel AD, et al. Quality of care in European home care programs using the second generation interRAI Home Care Quality Indicators (HCQIs). BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):148.

Lovheim H, et al. Sex differences in the prevalence of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(3):469–75.

Zuidema SU, et al. Predictors of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients: influence of gender and dementia severity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(10):1079–86.

Taipale H, et al. Antipsychotic doses among community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer disease in Finland. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34(4):435–40.

Rochon PA, et al. Older men with dementia are at greater risk than women of serious events after initiating antipsychotic therapy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):55–61.

Lucas C, Byles J, Martin JH. Medicines optimisation in older people: taking age and sex into account. Maturitas. 2016;93:114–20.

Beekly DL, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the uniform data set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):249–58.

Beekly DL, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: an Alzheimer disease database. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18(4):270–7.

Morris JC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4):210–6.

Weintraub S, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(2):91–101.

McKhann G, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–44.

WHO Collobarating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system: structure and principles. 2015. http://www.whocc.no/atc/structure_and_principles/. Accessed 15 Nov 2016.

Taipale H, et al. High prevalence of psychotropic drug use among persons with and without Alzheimer’s disease in Finnish nationwide cohort. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(11):1729–37.

Taipale H, et al. Antipsychotic polypharmacy among a nationwide sample of community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(4):1223–8.

Taipale H, et al. Antidementia drug use among community-dwelling individuals with Alzheimer’s disease in Finland: a nationwide register-based study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(4):216–23.

Tolppanen AM, et al. Use of existing data sources in clinical epidemiology: Finnish health care registers in Alzheimer’s disease research. The Medication use among persons with Alzheimer’s Disease (MEDALZ-2005) study. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:277–85.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Duodecim FMS. Current care: memory disorders [in Finnish with English summary]. 2010. http:\\www.kaypahoito.fi. Accessed 15 Nov 2016.

Taipale H, et al. Long-term use of benzodiazepines and related drugs among community-dwelling individuals with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(4):202–8.

Taipale H, et al. Hospital care and drug costs from five years before until two years after the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in a Finnish nationwide cohort. Scand J Public Health. 2016;44(2):150–8.

Tanskanen A, et al. From prescription drug purchases to drug use periods: a second generation method (PRE2DUP). BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:21.

Galobardes B, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2006;60(1):7–12.

Galobardes B, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2). J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2006;60(2):95–101.

Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–4.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ”Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

Cummings JL, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–14.

Kaufer DI, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–9.

Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5(1/2):65–173.

SAS Institute Inc. SAS version 9.4. Cary: SAS Institute Inc.; 2013.

Paulose-Ram R, et al. Trends in psychotropic medication use among U.S. adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(5):560–70.

Morgan SG, et al. Sex differences in the risk of receiving potentially inappropriate prescriptions among older adults. Age Ageing. 2016;45(4):535–42.

Petrovic M, et al. Personality traits and socio-epidemiological status of hospitalised elderly benzodiazepine users. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(8):733–8.

Kitamura T, et al. Gender differences in clinical manifestations and outcomes among hospitalized patients with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(12):1548–54.

Steinberg M, et al. Risk factors for neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(9):824–30.

Kales HC, et al. Trends in antipsychotic use in dementia 1999-2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(2):190–7.

Dutcher SK, et al. Effect of medications on physical function and cognition in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1046–55.

Author contributions

DM: study concept and design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, and preparation and editing of manuscript. HT: study concept and design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, and preparation and editing of manuscript. AMT: acquisition of data and interpretation, critical revising of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. AT: acquisition of data and interpretation, critical revising of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. JT: acquisition of data and interpretation, critical revising of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. SH: study concept and design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, and preparation and editing of manuscript. QW: data analysis, critical revising of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. GJ: study concept and design, interpretation of study findings, critical revising of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. DG: study concept and design, interpretation of findings, and preparation and editing of manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by Grant No. K12 DA035150 (Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health) from the National Institutes of Health, Office of Women’s Health Research and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DM) and National Health and Medical Research Early Career Fellowship (DG).

The NACC database is funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA)/National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed to by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI Marie-Francoise Chesselet, MD, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Conflict of interest

HT participated in research projects funded by Janssen with grants paid to an employer institution outside of this work. AT participated in research projects funded by Janssen with grants paid to Karolinska Institutet outside of this work. JT has served as a consultant to Lundbeck, Organon, Janssen-Cilag, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, F. Hoffman-La Roche, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and has received fees for giving expert opinions to Bristol-Myers Squibb and GlaxoSmithKline, lecture fees from Janssen-Cilag, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Lundbeck, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, and Novartis; and a grant from Stanley Foundation. JT is a member of the advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, and Otsuka. SH received lecture fees from MSD and Professio for providing lectures concerning medications in old age. DM, AMT, QW, GJ and DG declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Cohort data use was approved by local ethics committees at each institution and owing to the de-identified nature of the data included in our current study, informed consent was waived. Specifically, for the US data, the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center Clinical/Research Core protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kentucky. Ethics committee approval was not required for the MEDALZ cohort according to Finnish legislation as only register-based data were used and persons were not contacted.

Sponsor’s role

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moga, D.C., Taipale, H., Tolppanen, AM. et al. A Comparison of Sex Differences in Psychotropic Medication Use in Older People with Alzheimer’s Disease in the US and Finland. Drugs Aging 34, 55–65 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0419-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0419-5