Abstract

Stroke is a common cause of death and persisting disability worldwide, and thrombolysis with intravenous alteplase is the only approved treatment for acute ischaemic stroke. Older age is the most important non-modifiable risk factor for stroke, and demographic changes are also resulting in an increasingly ageing population. However, clinical trial evidence for the use of intravenous alteplase is limited for the older age group where stroke incidence is highest. In this article, the current evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of intravenous thrombolytic therapy in stroke patients aged ≥80 years is critically analysed and the gap in current knowledge highlighted. In summary, intravenous thrombolysis in stroke patients aged ≥80 years seems to be associated with less favourable clinical outcomes and higher mortality than in younger patients, which is consistent with the natural course in untreated patients. The risk of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage does not appear to be significantly higher in the elderly group, suggesting that intracranial bleeding complications are unlikely to outweigh the potential benefit in this age group. Overall, withholding thrombolytic treatment in ischaemic stroke on the basis of advanced age alone is no longer justifiable.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Stroke is the third most common cause of death worldwide and the leading cause of persisting disability, with up to half of all patients needing long-term healthcare [1–3]. Stroke is also estimated to become the leading cause of death in developed countries within the next 30 years [4]. Age is the most important non-modifiable risk factor for stroke and the rate doubles for each successive decade after the age of 55 years [5, 6]. Reports indicate that up to 90 % of strokes occur in patients aged >65 years [7, 8]. Of these strokes, half occur in patients aged ≥70 years and nearly a quarter in patients aged >85 years [7, 8]. Furthermore, demographic changes and medical advances are resulting in an increasingly older population. By 2025, the global population aged >60 years is estimated to rise to 1.2 billion—double the number of people above this age in 1995 [9]. By 2050, the number of people aged ≥65 years is expected to exceed those aged <65 years [10]. These data indicate that the incidence of stroke, especially in older people, will further increase in the near future. One report estimates that the global occurrence of first-ever strokes will increase to 18 million by 2015 [11]. Apart from the higher incidence, stroke in the elderly is also of concern because of the associated mortality and disability requiring assistance in daily living or institutionalization. The aim of this article is to analyse the safety and efficacy of intravenous thrombolytic therapy (IVT) with alteplase, which is the only approved treatment for acute ischaemic stroke, in older age.

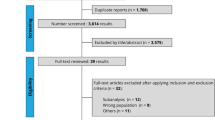

To identify relevant articles about IVT in older stroke patients, a PubMed search (1966 to 1 February 2012) was performed using the following terms: ‘ischemic stroke’, ‘thrombolysis’, ‘alteplase’, ‘elderly’, ‘old’ and ‘nonagenarians’. Additional reports were obtained by screening reference lists of the retrieved articles and reviews.

2 Intravenous Thrombolytic Therapy (IVT) and Stroke

IVT with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (alteplase) is a well proven treatment for acute ischaemic stroke. The recommended dose is 0.9 mg alteplase/kg body weight (maximum of 90 mg) infused intravenously over 60 min, with 10 % of the total dose administered as bolus. The NINDS study (see Table 1 for full names of trial acronyms used in this article) was the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) that proved efficacy of IVT in acute ischaemic stroke [12]. This study included 624 patients, with a mean age of 67 years, and showed that patients treated with IVT within 3 h after stroke onset were about 30 % more likely to have minimal or no disability at 3 months as compared with the placebo group. Considering benefits versus risks of treatment per 100 stroke patients, about 32 will benefit from treatment, while three will be harmed by alteplase-related intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) [13]. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved intravenous alteplase for the treatment of ischaemic stroke in 1996, 1 year after the publication of the NINDS trial. In Europe, this therapy received official approval in 2002 from the European Medicines Agency (EMA), but was restricted to patients aged ≤80 years. SITS-MOST, which was a register including 6,483 patients from 285 centres in 14 countries between 2002 and 2006, proved the safety and efficacy of IVT in routine clinical use, even in less experienced centres [14]. In the ECASS-3 study, which was published in 2008, a total of 821 patients were randomized between IVT and placebo in the 3- to 4.5-h time window [15]. Patients treated with alteplase had a 7.2 % absolute increase in the rate of excellent recovery at 3 months as compared with the placebo group. Meanwhile, several meta-analyses demonstrated the efficacy of IVT for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke [16–18].

3 IVT and Older Age

Contrary to the recommendations and conditions for use in the US, Canada and Switzerland, the EMA does not advocate the use of alteplase in the treatment of ischaemic stroke in patients aged >80 years [19]. One reason for this exclusion is that patients aged >80 years were not included in the large-scale European RCT [15, 20, 21]. The exclusion of this age group from treatment also led to the age limit of 80 years in SITS-MOST [14].

3.1 Randomized Trials

Clinical trial evidence for IVT in elderly stroke patients is limited, as most RCT excluded patients aged >80 years [15, 20–23]. Part 1 of the NINDS study used an upper age limit of 80 years for inclusion, which was subsequently removed in part 2 of the study. Overall, only 42 of 624 patients were aged over 80 years [12]. The exclusion of very old patients was primarily based on the assumed risk of ICH. However, the main determinants of ICH in the NINDS trial were stroke severity (measured by the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score) and early ischaemic changes on CT, whereas increasing age was not an independent predictor of symptomatic ICH (sICH) [24]. In addition, the post hoc analysis suggested a beneficial effect of alteplase across all age groups and did not support sub-selection of patients for IVT on the basis of age alone [25].

The results of IST-3 have recently been published [26]: in this multicentre, randomized, open-treatment trial, 3,035 patients were allocated either to intravenous alteplase up to 6 h from stroke onset or to control. There was no upper age limit for treatment: 1,617 (53 %) patients were older than 80 years of age. For the primary outcome (proportion of patients alive and independent at 6 months, as defined by an Oxford Handicap Score of 0–2), no significant differences were detected in the treatment and control groups (37 % vs. 35 %, adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.13, 95 % CI 0.95–1.35; p = 0.181). Interestingly, a significant difference was observed for the adjusted effect of treatment on the primary outcome between patients older than 80 years and patients 80 years or younger, suggesting even greater benefit in those older than 80 years of age [26]. In addition, most patients treated within 3 h were older than 80 years of age and achieved similar benefits to younger patients in NINDS [12, 26]. The authors concluded that the benefit of IVT did not seem to be diminished in elderly stroke patients.

3.2 Observational Studies

In view of the limited data from RCTs, most of the available evidence for use of IVT in elderly patients comes from observational single-centre or collaborative reports at both academic and community-based centres. Table 2 gives an overview of comparative studies that were identified from the literature search and lists their main findings. Of 20 studies, 18 separated the groups at the age of 80 years [27–41]. The dichotomization of age <80 and >80 years in most studies is related to the fact that patients aged >80 years were either excluded from or under-represented in large RCTs. The rates of sICH in the older age groups (≥80 years) were comparable to those in the younger counterparts (<80 years) in all but one study [29]. On the other hand, the association between unfavourable outcome and age ≥80 years was statistically significant in 6 of 14 studies [28, 29, 31, 33, 38, 39]. The association between mortality and age ≥80 years was evident in 9 of 14 studies [27, 28, 31–33, 37–39, 42]. The largest series were published by Ford and colleagues [38], reporting outcomes in 21,242 patients (1,831 aged >80 years), followed by Sylaja et al. [31] reporting on 1,135 patients (270 aged ≥80 years). Both studies revealed the same findings: the sICH risk was similar in the older and younger age groups, whereas unfavourable outcome and mortality were more frequently observed in patients aged >80 years.

Two studies compared the outcomes in octogenarians (80–90 years) versus nonagenarians (90–99 years) and reported conflicting results [43, 44]: both studies showed higher rates of sICH, unfavourable outcome and mortality in nonagenarians. While these differences were statistically not significant in the first study [43], a twofold increased probability for poor clinical outcome was observed in the other study [44].

Other observational studies focused on off-label use of thrombolysis (e.g. treatment beyond the 3-h time window, oral anticoagulation, NIHSS <5 or >25 points, previous history of stroke and diabetes mellitus) [45–49]. These studies also provide valuable estimates about IVT in patients aged >80 years (number of patients ranging from 91 [48] to 159 [47]). In general, older age was not significantly associated with increased risk of sICH, whereas age >80 years was independently associated with poor outcome in all studies [45–49].

3.3 Meta-Analyses

Engelter et al. performed a meta-analysis by comparing the stroke outcomes after IVT in patients aged ≥80 years versus <80 years [50]. They found that, first, stroke patients aged ≥80 years receiving alteplase had a threefold higher mortality risk than younger patients and were less likely to recover favourably at 3 months. Second, the risk of sICH was similar in both age groups. The authors referred to the European BIOMED Study of Stroke Care, which reported a similar OR [3.1 (95 % CI 2.7–3.7)] for 3-month mortality in stroke patients of the same age groups (≥80 years vs. <80 years) who were not treated with IVT [51]. Furthermore, the chance of a favourable outcome was also significantly lower in the older age group, as were the odds for being discharged home [OR 0.4 (95 % CI 0.4–0.5)] [51]. These comparisons indirectly suggested that treatment with alteplase probably did not contribute to the poorer outcomes in the older age group.

Bhatnagar et al. performed an update of this meta-analysis that included 13 studies and 3,484 stroke patients receiving IVT, with 764 (21.9 %) of them aged ≥80 years [52]. The results were comparable to the findings of Engelter et al. [50]: the overall OR was 2.8 for death (95 % CI 2.3–3.4) and 0.5 (95 % CI 0.4–0.6) for achieving a favourable outcome in patients ≥80 years as compared with their younger counterparts, whereas the rate of sICH was not significantly increased in the older group [OR 1.3 (95 % CI 0.9–1.8)].

Wardlaw and colleagues recently performed a meta-analysis to assess all the randomized evidence for IVT in acute ischaemic stroke [53]. They identified 12 RCTs (7,012 patients) of intravenous alteplase given up to 6 h after stroke onset. Three trials included a total of 1,711 patients older than 80 years (95 % from IST-3, the rest from EPITHET and NINDS) [12, 26, 53, 54]. The relative and absolute benefits of alteplase were similar in older and younger patients, while benefit was greatest for treatment within 3 h of stroke onset [53].

3.4 Natural History

Questions arise over whether or not the increased rates of unfavourable outcome and mortality in the older age group is directly related to adverse effects of alteplase in this age group. Here, the natural course of untreated stroke in elderly patients has to be considered. Advancing age has been shown to be an independent risk for increased mortality after ischaemic stroke [5, 55–64]. Stroke mortality rate was especially high in patients aged ≥75 years (up to 50 % within the first 3 months after stroke) [59, 60, 64, 65]. Pre-stroke institutionalization has been found to be a strong and independent determinant of 3-month disability in stroke patients aged ≥80 years [51]. Older patients not only have more severe stroke deficits at presentation but they also recover more slowly than younger patients [5, 55, 66]. One reason for the higher stroke severity in older age may be related to the increased frequency of atrial fibrillation (up to 30 % in people aged >80 years) [51]. Cardio-embolic strokes have been shown to have higher mortality than penetrating-artery or large-artery atherosclerotic infarcts [66, 67]. Other factors explaining the dramatic clinical effect of stroke in older patients are pre-stroke physical disabilities or cognitive disorders, multiple organ dysfunction (such as cardiac and renal co-morbidities), consumption of multiple medications and increased frequency of complications during hospitalization [51, 64, 66, 68, 69]. Elderly patients also receive a lower quality of stroke care, especially in terms of investigation, admission to stroke units, and access to early rehabilitation [51, 55, 58, 70]. Furthermore, a threefold higher risk of stroke recurrence was reported for patients aged >65 years after first ischaemic event as compared with younger patients [71].

Mishra and colleagues compared the outcomes in 23,334 patients from SITS who were treated with IVT versus 6,166 control patients from the VISTA neuroprotection trials who received no alteplase [72]. They demonstrated significant benefits from IVT among each 10-year age group up to 81–90 and 91–100 year groups. No interaction between age and efficacy of alteplase was found across the age range from 30 to 100 years. By examining outcomes separately among patients aged ≤80 years versus >80 years, the probability for favourable outcome was similar for each subgroup [72]. In addition, no significant difference in rates of sICH was observed among patients aged >80 years as compared with the younger cohort [72].

3.5 Other Confounders

Apart from the impact of natural history, some other factors may additionally contribute to poor clinical outcomes in the elderly age group. In most observational studies, baseline characteristics were to the disadvantage of the older group, such as over-representation of female sex, cardiac co-morbidity, pre-stroke disability, higher blood pressure or higher stroke severity. Female sex has been demonstrated to be an unfavourable outcome predictor [73, 74]. The functional outcome in older stroke patients was mainly determined by the status before admission to stroke rehabilitation, whereas age alone accounted for only 3 % of the variation in functional outcome [75]. Cardiac co-morbidity and higher blood pressure has been reported to predispose to poorer outcome or to increase the risk for haemorrhagic transformation, whereas stroke severity (measured by NIHSS) is known as the most important outcome predictor [76]. These imbalances are likely to contribute to the less favourable outcome among the older age group.

Several factors may theoretically increase the risk of ICH in older stroke patients undergoing treatment with IVT, such as higher frequency of microangiopathy (leukoaraiosis or cerebral amyloid angiopathy) [77], frail vasculature, and impaired rate of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) clearance [78]. Moderate or severe leukoaraiosis was shown to be a major risk of sICH in older stroke patients treated with IVT, whereas age itself was not found to be an independent predictor of ICH [79]. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy may lead to microvascular impairment and thus increase the risk of alteplase-related ICH. Age might be merely a ‘biological’ marker of the various age-linked degenerative processes such as cerebral microangiopathy, leukoaraiosis and cerebral amyloid angiopathy that may be associated with increased risk of ICH [19].

4 Gap of Knowledge and Limitations

In view of the sparse clinical trial evidence for IVT in elderly stroke patients, many observational cohort studies have attempted to obtain indirect evidence by comparing the outcomes in patients aged >80 years versus those aged <80 years. Given the high incidence of stroke in elderly patients and the lack of RCTs in this population, these studies may be the next appropriate approach. Still, a major gap remains in our knowledge related to IVT in older age, as observational studies may be prone to several biases. It is assumed that the older subjects participating in most studies were particularly healthy, whereas the younger patients were less carefully selected (selection bias). Thus, the frequency of pre-stroke disability among alteplase-treated older patients was lower than reported in unselected stroke registries (5–28 % vs. 45 %) [27, 31, 51]. The same is true for inclusion of patients with less severe strokes [80]. Authors may be less willing to publish results that contradict their belief (publication bias). This is especially true for studies related to the SITS as this is a voluntary register and does not include all patients treated with alteplase; patients with adverse events (such as sICH and death) may be omitted [81]. In SITS-MOST, however, source data verification was performed by monitors [14]. Another potential bias may be caused by loss to follow-up and/or protocol violations, especially differential loss to follow-up between the age groups [52]. Most observational studies were characterized by a small number of patients aged >80 years compared with their younger counterparts, suggesting selection bias and probably low power to detect clinically significant differences (type II error). Another limitation is the dichotomization of <80 and >80 years in many observational studies, although the relationship between age and outcome is likely to be gradual [82]. In addition, the findings may not apply to all stroke patients aged >80 years as substantially poorer outcomes have been reported for nonagenarians receiving IVT as compared with octogenarians [44]. Given these limitations, observational studies do not provide a substitute for RCT.

IST-3 is currently the largest-ever randomized trial of IVT for stroke in older people. However, one has to note that this study recruited only half the number of patients originally intended and thus might be underpowered to detect significant differences for the primary outcome [26, 83]. Furthermore, about three quarters of patients were treated beyond the conventional 3-h time window [26]. In addition, the significant interactions across age subgroups should be interpreted with caution in view of the overall non-significant benefit for the primary outcome [26].

The TESPI study is a randomized trial that aims to assess the safety and efficacy of intravenous alteplase given in patients aged >80 years and within 3 h after stroke onset [84]. A total of 600 patients are planned to be enrolled (300 in the alteplase arm, 300 in the non-treated control group) over a study period of 3 years. This study will provide valuable randomized trial evidence on the balance of risk and benefit of IVT in this increasing age group.

5 Conclusions

In summary, clinical trial evidence for the use of intravenous alteplase is limited for the older age group, where stroke incidence is highest. IVT in stroke patients aged >80 years seems to be associated with less favourable clinical outcomes and higher mortality than in younger patients. However, this observation is consistent with the overall poorer prognosis known from the natural history of elderly stroke patients not treated with alteplase. Imbalances in outcome-predictive baseline variables to the disadvantage of the older age group may additionally influence the clinical outcomes. On the other hand, the risk of sICH does not appear to be significantly higher in the elderly group, suggesting that intracranial bleeding complications are unlikely to outweigh the potential benefit in this age group. These data indicate that withholding IVT in ischaemic stroke on the basis of advanced age alone is no longer justifiable. In addition, the European and American stroke guidelines support treatment with alteplase in selected elderly patients [85, 86]. The TESPI trial is expected to yield more conclusive randomized evidence on this topic [84].

References

Di Carlo A. Human and economic burden of stroke. Age Ageing. 2009;38(1):4–5.

Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9063):1436–42.

Sturm JW, Donnan GA, Dewey HM, Macdonell RA, Gilligan AK, Srikanth V, et al. Quality of life after stroke: the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Stroke. 2004;35(10):2340–5.

Sanossian N, Ovbiagele B. Prevention and management of stroke in very elderly patients. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(11):1031–41.

Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Silver LE, Fairhead JF, Giles MF, Lovelock CE, et al. Population-based study of event-rate, incidence, case fatality, and mortality for all acute vascular events in all arterial territories (Oxford Vascular Study). Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1773–83.

Rojas JI, Zurru MC, Romano M, Patrucco L, Cristiano E. Acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack in the very old: risk factor profile and stroke subtype between patients older than 80 years and patients aged less than 80 years. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(8):895–9.

Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Anderson CS. Stroke epidemiology: a review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(1):43–53.

Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2008 update. A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117(4):e25–146.

Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–8.

Powell JL, Cook IG. Global ageing in comparative perspective: a critical discussion. Int J Soc Policy. 2009;29:388–400.

Strong K, Mathers C, Bonita R. Preventing stroke: saving lives around the world. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):182–7.

Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581–7.

Saver JL. Number needed to treat estimates incorporating effects over the entire range of clinical outcomes: novel derivation method and application to thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(7):1066–70.

Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Davalos A, Ford GA, Grond M, Hacke W, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): an observational study. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):275–82.

Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(13):1317–29.

Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, Kaste M, von Kummer R, Broderick JP, et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):768–74.

Lansberg MG, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke: a metaanalysis. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2438–41.

Wardlaw JM, Murray V, Berge E, Del Zoppo GJ. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(4):CD000213.

Derex L, Nighoghossian N. Thrombolysis, stroke-unit admission and early rehabilitation in elderly patients. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(9):506–11.

Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, Toni D, Lesaffre E, von Kummer R, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke. The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS). JAMA. 1995;274(13):1017–25.

Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998;352(9136):1245–51.

Clark WM, Wissman S, Albers GW, Jhamandas JH, Madden KP, Hamilton S. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (Alteplase) for ischemic stroke 3 to 5 hours after symptom onset. The ATLANTIS Study: a randomized controlled trial. Alteplase Thrombolysis for Acute Noninterventional Therapy in Ischemic Stroke. JAMA. 1999;282(21):2019–26.

Clark WM, Albers GW, Madden KP, Hamilton S. The rtPA (alteplase) 0- to 6-hour acute stroke trial, part A (A0276 g): results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Thromblytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke study investigators. Stroke. 2000;31(4):811–6.

Intracerebral hemorrhage after intravenous t-PA therapy for ischemic stroke. The NINDS t-PA Stroke Study Group. Stroke. 1997;28(11):2109–18.

No authors listed. Generalized efficacy of t-PA for acute stroke: subgroup analysis of the NINDS t-PA Stroke Trial. Stroke. 1997;28(11):2119–25.

IST-3 collaborative group, Sandercock P, Wardlaw JM, Lindley RI, Dennis M, Cohen G, et al. The benefits and harms of intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke (the third international stroke trial [IST-3]): a randomised controlled trial [published erratum appears in Lancet 2012 Aug 25;380(9843):730]. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2352–63.

Engelter ST, Reichhart M, Sekoranja L, Georgiadis D, Baumann A, Weder B, et al. Thrombolysis in stroke patients aged 80 years and older: Swiss survey of IV thrombolysis. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1795–8.

Mouradian MS, Senthilselvan A, Jickling G, McCombe JA, Emery DJ, Dean N, et al. Intravenous rt-PA for acute stroke: comparing its effectiveness in younger and older patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(9):1234–7.

van Oostenbrugge RJ, Hupperts RM, Lodder J. Thrombolysis for acute stroke with special emphasis on the very old: experience from a single Dutch centre. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(3):375–7.

Parnetti L, Silvestrelli G, Lanari A, Tambasco N, Capocchi G, Agnelli G. Efficacy of thrombolytic (rt-PA) therapy in old stroke patients: the Perugia Stroke Unit experience. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2006;28(3–4):397–404.

Sylaja PN, Cote R, Buchan AM, Hill MD. Thrombolysis in patients older than 80 years with acute ischaemic stroke: Canadian Alteplase for Stroke Effectiveness Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(7):826–9.

Ringleb PA, Schwark C, Kohrmann M, Kulkens S, Juttler E, Hacke W, et al. Thrombolytic therapy for acute ischaemic stroke in octogenarians: selection by magnetic resonance imaging improves safety but does not improve outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(7):690–3.

Uyttenboogaart M, Schrijvers EM, Vroomen PC, De Keyser J, Luijckx GJ. Routine thrombolysis with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischaemic stroke patients aged 80 years or older: a single centre experience. Age Ageing. 2007;36(5):577–9.

Gomez-Choco M, Obach V, Urra X, Amaro S, Cervera A, Vargas M, et al. The response to IV rt-PA in very old stroke patients. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(3):253–6.

Meseguer E, Labreuche J, Olivot JM, Abboud H, Lavallee PC, Simon O, et al. Determinants of outcome and safety of intravenous rt-PA therapy in the very old: a clinical registry study and systematic review. Age Ageing. 2008;37(1):107–11.

Pundik S, McWilliams-Dunnigan L, Blackham KL, Kirchner HL, Sundararajan S, Sunshine JL, et al. Older age does not increase risk of hemorrhagic complications after intravenous and/or intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;17(5):266–72.

Toni D, Lorenzano S, Agnelli G, Guidetti D, Orlandi G, Semplicini A, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with rt-PA in acute ischemic stroke patients aged older than 80 years in Italy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25(1–2):129–35.

Ford GA, Ahmed N, Azevedo E, Grond M, Larrue V, Lindsberg PJ, et al. Intravenous alteplase for stroke in those older than 80 years old. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2568–74.

Boulouis G, Dumont F, Cordonnier C, Bodenant M, Leys D, Henon H. Intravenous thrombolysis for acute cerebral ischaemia in old stroke patients >/=80 years of age. J Neurol. 2012;259(7):1461–7.

Dharmasaroja PA, Muengtaweepongsa S, Dharmasaroja P. Intravenous thrombolysis in Thai patients with acute ischemic stroke: role of aging. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (Epub 2011 Dec 14).

Costello CA, Campbell BC. Perez de la Ossa N, Zheng TH, Sherwin JC, Weir L, et al. Age over 80 years is not associated with increased hemorrhagic transformation after stroke thrombolysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(3):360–3.

Tanne D, Kasner SE, Demchuk AM, Koren-Morag N, Hanson S, Grond M, et al. Markers of increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage after intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator therapy for acute ischemic stroke in clinical practice: the Multicenter rt-PA Stroke Survey. Circulation. 2002;105(14):1679–85.

Mateen FJ, Buchan AM, Hill MD. Outcomes of thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke in octogenarians versus nonagenarians. Stroke. 2010;41(8):1833–5.

Sarikaya H, Arnold M, Engelter ST, Lyrer PA, Michel P, Odier C, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in nonagenarians with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(7):1967–70.

Breuer L, Blinzler C, Huttner HB, Kiphuth IC, Schwab S, Kohrmann M. Off-label thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: rate, clinical outcome and safety are influenced by the definition of ‘minor stroke’. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32(2):177–85.

Guillan M, Alonso-Canovas A, Garcia-Caldentey J, Sanchez-Gonzalez V, Hernandez-Medrano I, Defelipe-Mimbrera A, et al. Off-label intravenous thrombolysis in acute stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(3):390–4.

Meretoja A, Putaala J, Tatlisumak T, Atula S, Artto V, Curtze S, et al. Off-label thrombolysis is not associated with poor outcome in patients with stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(7):1450–8.

Rubiera M, Ribo M, Santamarina E, Maisterra O, Delgado-Mederos R, Delgado P, et al. Is it time to reassess the SITS-MOST criteria for thrombolysis? A comparison of patients with and without SITS-MOST exclusion criteria. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2568–71.

The SITS-EAST Collaborative Group. Intravenous alteplase in ischemic stroke patients not fully adhering to the current drug license in Central and Eastern Europe. Int J Stroke. 2012;7(8):615–22.

Engelter ST, Bonati LH, Lyrer PA. Intravenous thrombolysis in stroke patients of > or =80 versus <80 years of age: a systematic review across cohort studies. Age Ageing. 2006;35(6):572–80.

Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Pracucci G, Basile AM, Trefoloni G, Vanni P, et al. Stroke in the very old: clinical presentation and determinants of 3-month functional outcome. A European perspective. European BIOMED Study of Stroke Care Group. Stroke. 1999;30(11):2313–9.

Bhatnagar P, Sinha D, Parker RA, Guyler P, O’Brien A. Intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischaemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis to aid decision making in patients over 80 years of age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(7):712–7.

Wardlaw JM, Murray V, Berge E, Del Zoppo G, Sandercock P, Lindley RL, et al. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischaemic stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2364–72.

Davis SM, Donnan GA, Parsons MW, Levi C, Butcher KS, Peeters A, et al. Effects of alteplase beyond 3 h after stroke in the Echoplanar Imaging Thrombolytic Evaluation Trial (EPITHET): a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):299–309.

Marini C, Baldassarre M, Russo T, De Santis F, Sacco S, Ciancarelli I, et al. Burden of first-ever ischemic stroke in the oldest old: evidence from a population-based study. Neurology. 2004;62(1):77–81.

Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Zhao X, Olson DM, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Age-related differences in characteristics, performance measures, treatment trends, and outcomes in patients with ischemic stroke. Circulation. 2010;121(7):879–91.

Saposnik G, Hill MD, O’Donnell M, Fang J, Hachinski V, Kapral MK. Variables associated with 7-day, 30-day, and 1-year fatality after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2008;39(8):2318–24.

Palnum KD, Petersen P, Sorensen HT, Ingeman A, Mainz J, Bartels P, et al. Older patients with acute stroke in Denmark: quality of care and short-term mortality. A nationwide follow-up study. Age Ageing. 2008;37(1):90–5.

Carter AM, Catto AJ, Mansfield MW, Bamford JM, Grant PJ. Predictive variables for mortality after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2007;38(6):1873–80.

Collins TC, Petersen NJ, Menke TJ, Souchek J, Foster W, Ashton CM. Short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term mortality in patients hospitalized for stroke. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(1):81–7.

Asplund K, Carlberg B, Sundstrom G. Stroke in the elderly: observations in a population-based sample of hospitalized patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1992;2(3):152–7.

Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation: a major contributor to stroke in the elderly. The Framingham Study. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(9):1561–4.

Bamford J, Dennis M, Sandercock P, Burn J, Warlow C. The frequency, causes and timing of death within 30 days of a first stroke: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53(10):824–9.

Sharma JC, Fletcher S, Vassallo M. Strokes in the elderly—higher acute and 3-month mortality—an explanation. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999;9(1):2–9.

Steger C, Pratter A, Martinek-Bregel M, Avanzini M, Valentin A, Slany J, et al. Stroke patients with atrial fibrillation have a worse prognosis than patients without: data from the Austrian Stroke registry. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(19):1734–40.

Kammersgaard LP, Jorgensen HS, Reith J, Nakayama H, Pedersen PM, Olsen TS. Short- and long-term prognosis for very old stroke patients. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):149–54.

Petty GW, Brown RD Jr, Whisnant JP, Sicks JD, O’Fallon WM, Wiebers DO. Ischemic stroke subtypes: a population-based study of functional outcome, survival, and recurrence. Stroke. 2000;31(5):1062–8.

Olindo S, Cabre P, Deschamps R, Chatot-Henry C, Rene-Corail P, Fournerie P, et al. Acute stroke in the very elderly: epidemiological features, stroke subtypes, management, and outcome in Martinique. French West Indies. Stroke. 2003;34(7):1593–7.

Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. Am J Med. 1995;98(5):476–84.

Kaste M, Palomaki H, Sarna S. Where and how should elderly stroke patients be treated? A randomized trial. Stroke. 1995;26(2):249–53.

Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2901–6.

Mishra NK, Ahmed N, Andersen G, Egido JA, Lindsberg PJ, Ringleb PA, et al. Thrombolysis in very elderly people: controlled comparison of SITS International Stroke Thrombolysis Registry and Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive. BMJs. 2010;341:c6046.

Weimar C, Ziegler A, Konig IR, Diener HC. Predicting functional outcome and survival after acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol. 2002;249(7):888–95.

Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Baldereschi M, Pracucci G, Basile AM, Wolfe CD, et al. Sex differences in the clinical presentation, resource use, and 3-month outcome of acute stroke in Europe: data from a multicenter multinational hospital-based registry. Stroke. 2003;34(5):1114–9.

Bagg S, Pombo AP, Hopman W. Effect of age on functional outcomes after stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 2002;33(1):179–85.

Demchuk AM, Tanne D, Hill MD, Kasner SE, Hanson S, Grond M, et al. Predictors of good outcome after intravenous tPA for acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2001;57(3):474–80.

Greenberg SM, Vonsattel JP. Diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: sensitivity and specificity of cortical biopsy. Stroke. 1997;28(7):1418–22.

de Boer A, Kluft C, Kroon JM, Kasper FJ, Schoemaker HC, Pruis J, et al. Liver blood flow as a major determinant of the clearance of recombinant human tissue-type plasminogen activator. Thromb Haemost. 1992;67(1):83–7.

Neumann-Haefelin T, Hoelig S, Berkefeld J, Fiehler J, Gass A, Humpich M, et al. Leukoaraiosis is a risk factor for symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after thrombolysis for acute stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(10):2463–6.

Vatankhah B, Dittmar MS, Fehm NP, Erban P, Ickenstein GW, Jakob W, et al. Thrombolysis for stroke in the elderly. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2005;20(1):5–10.

Lindley RI, Wardlaw JM, Sandercock PA. Thrombolysis in elderly people: observational data insufficient to change treatment. BMJ. 2011;342:d306 (author reply d12).

Berrouschot J, Rother J, Glahn J, Kucinski T, Fiehler J, Thomalla G. Outcome and severe hemorrhagic complications of intravenous thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator in very old (> or =80 years) stroke patients. Stroke. 2005;36(11):2421–5.

Lyden PD. In anticipation of International Stroke Trial-3 (IST-3). Stroke. 2012;43(6):1691–4.

Lorenzano S, Toni D. TESPI (Thrombolysis in Elderly Stroke Patients in Italy): a randomized controlled trial of alteplase (rt-PA) versus standard treatment in acute ischaemic stroke in patients aged more than 80 years where thrombolysis is initiated within three hours after stroke onset. Int J Stroke. 2012;7(3):250–7.

European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Executive Committee; ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2008. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25(5):457–507.

Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Circulation. 2007;115(20):e478–534.

Tanne D, Gorman MJ, Bates VE, et al. Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke in patients aged 80 years and older: the tPA stroke survey experience. Stroke. 2000;31(2):370–5.

Chen CI, Iguchi Y, Grotta JC, et al. Intravenous TPA for very old stroke patients. Eur Neurol. 2005;54(3):140–4.

Acknowledgments

There is no funding and no conflict of interest in connection with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sarikaya, H. Safety and Efficacy of Thrombolysis with Intravenous Alteplase in Older Stroke Patients. Drugs Aging 30, 227–234 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0052-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0052-5