Abstract

Patient-centeredness has become an acknowledged hallmark of not only high-quality health care but also high-quality drug development. Biopharmaceutical companies are actively seeking to be more patient-centric in drug research and development by involving patients in identifying target disease conditions, participating in the design of, and recruitment for, clinical trials, and disseminating study results. Drug safety departments within the biopharmaceutical industry are at a similar inflection point. Rising rates of per capita prescription drug use underscore the importance of having robust pharmacovigilance systems in place to detect and assess adverse drug reactions (ADRs). At the same time, the practice of pharmacovigilance is being transformed by a host of recent regulatory guidances and related initiatives which emphasize the importance of the patient’s perspective in drug safety. Collectively, these initiatives impact the full range of activities that fall within the remit of pharmacovigilance, including ADR reporting, signal detection and evaluation, risk management, medication error assessment, benefit–risk assessment and risk communication. Examples include the fact that manufacturing authorization holders are now expected to monitor all digital sources under their control for potential reports of ADRs, and the emergence of new methods for collecting, analysing and reporting patient-generated ADR reports for signal detection and evaluation purposes. A drug safety department’s ability to transition successfully into a more patient-centric organization will depend on three defining attributes: (1) a patient-centered culture; (2) deployment of a framework to guide patient engagement activities; and (3) demonstrated proficiency in patient-centered competencies, including patient engagement, risk communication and patient preference assessment. Whether, and to what extent, drug safety departments embrace the new patient-centric imperative, and the methods and processes they implement to achieve this end effectively and efficiently, promise to become distinguishing factors in the highly competitive biopharmaceutical industry landscape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Patient-centeredness has become an acknowledged hallmark of not only high-quality health care but also high-quality drug development. |

Recent patient-centric regulatory and related initiatives are transforming the form and function of the pharmacovigilance function within the biopharmaceutical industry. |

To meet this patient-centric imperative successfully, pharmacovigilance departments will need to develop a more patient-centered culture, use a framework-driven approach to patient engagement and become proficient in a range of patient-centered competencies. |

1 Introduction

Patient-centeredness has become an acknowledged hallmark of not only high-quality health care but also high-quality drug development [1, 2]. Biopharmaceutical companies are actively seeking to be more patient-centric in drug research and development by involving patients in identifying target disease conditions; participating in the design of, and recruitment for, clinical trials; and disseminating study results [3, 4].

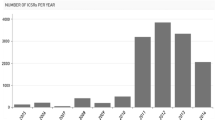

Drug safety departments within the biopharmaceutical industry are at a similar inflection point. On the one hand, rising rates of per capita prescription drug use underscore the importance of having robust pharmacovigilance systems in place to detect and assess adverse drug reactions (ADRs) [4]. At the same time, both the process and the practice of pharmacovigilance are being transformed by a host of patient-centric trends [5]. Given the critical role patients have to play in safe and appropriate use of medications, such a transformation is welcome, if not long overdue [6–8]. This development, however, challenges entrenched notions of the role and outputs of the pharmacovigilance function. Nonetheless, marketing authorization holders (MAHs) who are able to navigate this new terrain proactively will benefit in terms of an enhanced patient experience, improved patient safety outcomes and a competitive advantage in the evolving regulatory and payer landscape [4].

2 Patient-Centric Trends Affecting Drug Safety

‘Patient-centeredness’ or ‘patient-centricity’ is defined as an understanding of the patient’s perspective concerning his/her health condition and treatment experiences [9]. In recent years, a series of regulatory guidances and other initiatives have emerged, which effectively expand the ability of drug safety departments to understand and incorporate the patient’s perspective into pharmacovigilance activities (Table 1). Collectively, these initiatives impact the full range of activities that fall within the remit of pharmacovigilance, including ADR reporting, signal detection and evaluation, risk management, medication error assessment, benefit–risk assessment and risk communication. MAHs, for example, are now expected to monitor all digital sources under their control for potential reports of ADRs [10]. A new measurement system, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE), has been developed to improve the precision and reliability of patient-reported adverse events in clinical trials.

In addition, under the aegis of the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI)’s Web-Recognizing Adverse Drug Reactions (Web-RADR) project, robust methods have been advanced for collecting, analysing and reporting patient-generated ADR reports for signal detection and evaluation purposes, and patient ADR reporting has been further facilitated by the development of a mobile reporting app [11–17].

The value of obtaining the patient perspective regarding the benefit–risk profile of medicinal products is being increasingly acknowledged by regulatory authorities. In particular, recent revisions of the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) M4E Guideline specify where to include such data in the integrated benefit–risk section of the clinical overview for marketing authorization applications [18]. Relatedly, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has defined acceptable scientific methods to use in obtaining patient preference data for medical devices and has specified how such data can be included not only in the marketing authorization application but also in the label [19]. Both the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) advocate for sponsors to conduct human factors testing (‘simulated use testing’) in patients in order to understand whether product instructions for use are sufficiently clear [20, 21]. Similarly, both the EMA and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) recommend that risk communication measures be tested for patient comprehension and that patient input be elicited regarding the feasibility and acceptability of any proposed ‘additional risk minimization measures’ [22, 23].

Many of these recent developments impose new and/or enhanced responsibilities on pharmacovigilance departments. Similarly, implementing these patient-centric initiatives may present new or added complexities and challenges. A fundamental concern and challenge will be to ensure that the privacy of patient data is adequately safeguarded. Other challenges include the need to apply scientifically rigorous patient data collection methods that are applicable across a range of healthcare settings (e.g. inpatient versus outpatient), and to develop patient communication and training materials that are sensitive to demographic, cultural and linguistic heterogeneity within and across populations. Requests for patient input must be appropriately balanced so as to avoid over-burdening patients who are taking multiple drugs from different MAHs. Not least, it will be important to continue supporting advances in the science of patient preference assessment such that these data can be used to inform regulatory authority assessments of the product benefit–risk profile and, potentially, incorporated into product labelling as well.

Significantly, however, these developments also offer new opportunities for proactively engaging with patients not only in the safety evidence generation process but also for the purposes of supporting safe and appropriate product use (Fig. 1). Such opportunities include use of eHealth methods such as ‘gamification’ (video game-based techniques that create virtual simulations of real-world use scenarios) to reinforce safe use messaging and practices, and use of animated text and graphics to convey drug benefit–risk statistics [24, 25]. Similarly, new evaluative techniques can be employed to determine the comprehensibility of patient-targeted safety information—including, for example, the ‘teach-back method’, which requires patients to describe, in their own words, their understanding of the safety information [26].

Source: Adapted with permission from PatientsLikeMe from slide presented by S. Okun at “REMS Impact on Healthcare Delivery System and Patient Access,” Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Public Workshop, October 5, 2015, Rockville, MD, Docket No. FDA-2013-N-0502

The patient journey: key potential points of engagement between patients and drug safety.

3 Key Attributes of the Patient-Centered Drug Safety Department

Drug safety departments that are able to successfully transition into a more patient-centric organization will possess three defining attributes or ‘hallmarks’. These include (1) a patient-centered culture; (2) a framework to guide patient engagement activities; and (3) being conversant in applying a range of patient engagement methods and other patient-centered competencies. Strategic objectives and supporting tactics that can assist in this transition are outlined in Table 2.

3.1 A Culture of Patient-Centeredness

A key organizational attribute is a culture of patient-centeredness, one that emphasizes the importance of understanding the patient’s needs and goals for treatment, and the patient’s experience, or ‘journey’, in regard to illness and medical therapies. Such a culture clearly explicates the link between the patient and the work of individuals within the pharmacovigilance organization. Among the possible tactics that can be used to achieve a patient-centered culture, the most critical ones include senior management support, alignment with a supportive governance structure, establishment of performance metrics around patient engagement and provision of ongoing training to ensure that staff behaviours are consistent with a patient-centered cultural norm.

3.2 A Framework for Patient Engagement

The purpose of a framework is to provide a systematic, integrated, comprehensive and transparent process for patient engagement, and to facilitate cross-functional collaboration and sharing of patient-generated data. A framework outlines when, where and how patients are to be engaged at different junctures in the pharmacovigilance process, and the resources needed to achieve such engagement [4]. A framework can also serve as the linchpin that supports the development and implementation of policies for patient engagement, training, and communicating and reinforcing normative expectations for what it means to be an ‘activated’, empowered patient. Not least, a patient engagement framework should also specify metrics to evaluate both the quantity and the quality of patient engagement at defined points throughout the product life cycle.

3.3 Proficiency in Patient Engagement Methods

The patient-centered pharmacovigilance department of the future will also exhibit a number of key competencies (Table 3). These competencies can be acquired by hiring new professionals with relevant credentials, cultivating in-house talent by investing in staff training, and/or outsourcing to vendors with the requisite types of expertise. Examples of key competencies include fostering a patient-centered ethos within the organization, increasing patient access to understandable information via routine application of health literacy principles in the development of patient labelling and other patient-targeted risk communication materials, and the ability to obtain and integrate patient perspectives and preferences into relevant aspects of pharmacovigilance activities, such as product benefit–risk assessment, and risk management planning and evaluation [27].

4 Conclusion

Patient-centricity is transforming the form and function of pharmacovigilance. Partnering with patients to develop new medicinal products and devices that meet patients’ needs under real-world use conditions will involve a significant change in organizational culture. How drug safety departments, as well as biopharmaceutical companies as a whole, grapple with addressing this new, patient-centric imperative—and what methods and processes they implement to achieve this end effectively and efficiently—will be distinguishing factors in the highly competitive industry landscape. While currently there is no consensus regarding the optimal approach for engaging with patients, drug safety departments that invest in developing an internal patient-centered ‘ecosystem,’ including appropriate infrastructure and competencies, will be well-positioned to embrace this new era.

References

Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America, Consensus Report. Washington, DC: NAS Press; 2012.

Topel E. The patient will see you now: the future of medicine is in your hands. New York: Basic Books; 2015.

Thornton H. Patient and public involvement in clinical trials. BMJ. 2008;336:903–4.

Hoos A, Anderson J, Boutin M, Dewulf L, Geissler J, Johnston G, Joos A, Metcalf M, Regnante J, Sargeant I, Schneider RF, Todaro V, Tougas G. Partnering with patients in the development and lifecycle of medicines: a call for action. Ther Innov Reg Sci. 2015;49(6):929–39. doi:10.1177/2168479015580384.

Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818–31.

Inman WHW. Don’t tell the patient: behind the drug safety net. Los Angeles: Highland Park Productions; 1999.

Vincent CA, Coulter A. Patient safety: what about the patient? Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:76–80.

Budnitz DS, Layde PM. Outpatient drug safety: new steps in an older direction. Pharmacoepidem Drug Saf. 2007;16:160–5.

Hibbard J. Engaging health care consumers to improve the quality of care. Med Care. 2003;41(1):61–70.

European Medicines Agency [EMA]. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP), module VI—management and reporting of adverse reactions to medicinal products [EMA/873138/2011 Rev. 1]. London: EMA; 2014. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/09/WC500172402.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2016.

US National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Healthcare Delivery Research Program. Patient-reported outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE™). http://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae.

Basch E. Systematic collection of patient-reported adverse drug reactions: a path to patient-centered pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf. 2013;36(4):277–8.

Banerjee AK, Okun S, Edwards IR, Wicks P, Smith MY, Mayall S, Flamion B, Cleeland C, Basch E. Patient-reported outcome measures in safety reporting: PROSPER Consortium guidance. Drug Saf. 2013;36(12):1129–49.

Bahk CY, Goshgarian M, Donahue K, Freifeld CC, Menonel CM, Pierce CE, Rodriquez H, Brownstein JS, Furberg R, Dasgupta N. Increasing patient engagement in pharmacovigilance through online community outreach and mobile reporting applications: an analysis of adverse event reporting for the Essure device. Pharm Med. 2015;29(6):331–40. doi:10.1007/s40290-015-0106-6.

Ghosh R, Lewis D. Aims and approaches of Web-RADR: a consortium ensuring reliable ADR reporting via mobile devices and new insights from social media. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(12):1845–53.

Li Y, Ryan PB, Wei Y, Friedman C. A method to combine signals from spontaneous reporting systems and observational healthcare data to detect adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf. 2015;38:895–908. doi:10.1007/s4026-015-0314-8.

Yang M, Kiang M, Shang W. Filtering big data from social media: building an early warning system for adverse drug reactions. J Biomed Inf. 2015;54:230–40.

International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use [ICH]. Revision of M4E guideline on enhancing the format and structure of benefit–risk information in ICH. Step 3 version, dated November 2015. Geneva: ICH; 2015.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Patient preference information—submission, review in PMAs, HDE applications, and de novo requests, and inclusion in device labeling: draft guidance for industry, Food and Drug Administration staff, and other stakeholders. Silver Spring: Center for Devices and Radiologic Health; 2015. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm446680.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2016.

European Medicines Agency [EMA]. Good practice guide on risk minimisation and prevention of medication errors [EMA/606103/2014]. London: EMA; 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Regulatory_and_procedural_guideline/2015/11/WC500196981.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2016.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research [CDER]. Guidance for industry: safety considerations for product design to minimize medication errors. Silver Spring: CDER; 2012. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm331810.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2016.

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences [CIOMS]. Report of CIOMS Working Group IX: practical approaches to risk minimisation for medicinal products. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

European Medicines Agency [EMA]. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP): module V—risk management systems [EMA/838713/2011 Rev 1]. London: EMA; 2014. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2012/06/WC500129134.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2016.

Miller AS, Cafazzo JA, Seto E. A game plan: gamification design principles in mHealth applications for chronic disease management. Health Informatics J. doi:10.1177/1460458214537511 [Epub 2014 Jul 1].

Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Brennan-Martinez C, McGonegal M, Levine R. Using animated computer-generated text and graphics to depict the risks and benefits of medical treatment. Am J Med. 2012;125(11):1103–10.

Koh HK, Rudd RE. The arc of health literacy. JAMA. 2015;314(12):1225–6.

Bernabeo E, Holmboe ES. Patients, providers, and systems need to acquire a specific set of competencies to achieve truly patient-centered care. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):250–8.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed herein represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or practices of the authors’ employer or any other party.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Meredith Y. Smith and Isma Benattia are full-time employees of Amgen, Inc., a biopharmaceutical company, and own Amgen stock.

Funding

No sources of funding were used in the preparation of this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, M.Y., Benattia, I. The Patient’s Voice in Pharmacovigilance: Pragmatic Approaches to Building a Patient-Centric Drug Safety Organization. Drug Saf 39, 779–785 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0426-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0426-9