Abstract

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this review was to summarise current evidence that some environmental chemicals may be able to interfere in the endocrine regulation of energy metabolism and adipose tissue structure.

Recent Findings

Recent findings demonstrate that such endocrine-disrupting chemicals, termed “obesogens”, can promote adipogenesis and cause weight gain. This includes compounds to which the human population is exposed in daily life through their use in pesticides/herbicides, industrial and household products, plastics, detergents, flame retardants and as ingredients in personal care products. Animal models and epidemiological studies have shown that an especially sensitive time for exposure is in utero or the neonatal period.

Summary

In summarising the actions of obesogens, it is noteworthy that as their structures are mainly lipophilic, their ability to increase fat deposition has the added consequence of increasing the capacity for their own retention. This has the potential for a vicious spiral not only of increasing obesity but also increasing the retention of other lipophilic pollutant chemicals with an even broader range of adverse actions. This might offer an explanation as to why obesity is an underlying risk factor for so many diseases including cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The endocrine system plays a fundamental role in regulating the metabolism of fats, carbohydrates and proteins and in ensuring that these fuels provide for the energy needs of the body at all times. Hormones are responsible for storage of excess fuel in times of plenty and mobilisation of fuel in times of need, and most notably in maintaining constant levels of blood glucose. Any alteration to these hormonally driven processes can be expected to lead to an imbalance in metabolism. The main store of energy in the body is provided by fat held in adipocytes in the adipose tissue, and it is now recognised that the adipose tissue is also under endocrine control and can itself act as an endocrine organ capable of secreting hormones [1]. Interference in hormonal control of adipose tissue functions can therefore also lead to inappropriate deposits of fat and, hence, obesity.

Over recent years, many environmental chemicals have been shown to disrupt the actions of hormones and have been termed endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) or endocrine disruptors [2•]. Although much of the research has focused on disruption of reproduction through interference with steroid hormone actions and on disruption to thyroid hormone action [2•], there are increasing reports that some EDCs can also interfere with regulatory processes in metabolism and in the control of adipocyte function, resulting in imbalances in the regulation of body weight, which can lead to obesity [3•, 4•, 5•]. Such chemicals have been termed “obesogens” [6, 7•]. Increase in obesity, defined as a body mass index of over 30 kg/m2, has become a global problem over recent decades. Over 20% of adults are now obese in the UK and over 30% of adults are obese in the USA [8•]. Furthermore, obesity in children is also increasing in westernised countries, and in the USA, around 20% of children aged 3–17 years are obese [8•]. Although there are genetic determinants which lead to inherited predisposition, and there are environmental influences from excessive food intake combined with lack of exercise in modern life, these alone cannot account for the current disease trends. This review will present evidence that EDCs may contribute to obesity through interfering with the control of energy metabolism and adipose tissue regulation, causing an altered balance towards weight gain and obesity, despite normal diet and exercise patterns.

Sources of Endocrine Disruptors

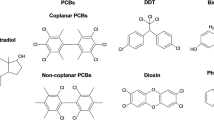

An endocrine disruptor has been defined as “an exogenous substance that causes adverse health effects in an intact organism, and/or its progeny, consequent to changes in endocrine function” [9]. Some of these compounds are present in nature (e.g. plant phytoestrogens), but the majority are synthetic chemicals which have been released by human activities into the environment without any prior knowledge of their effects on ecosystems or human health. The human population is now ubiquitously exposed to such chemicals in daily life, in indoor as well as outdoor environments, through their use in pesticides/herbicides, industrial and household products, plastics, detergents, flame retardants and as ingredients of personal care products [2•]. Intake to the human body may be oral, inhalation or dermal absorption [2•]. Figure 1 indicates some of the subset of endocrine disruptors which have been shown to possess obesogenic properties: their origins and endocrine-disrupting activities are outlined below, and the remainder of the review will discuss the evidence that they possess also obesogenic properties.

-

Tributyltin (TBT) is an environmental contaminant from its use as a biocide in antifouling paints applied to the hulls of ships, and it has been reported to cause imposex in molluscs and to masculinise female fish [10]. TBT can inhibit aromatase, which is the enzyme responsible for the conversion of testosterone into estrogens [11, 12].

-

Diethylstilbestrol (DES) is a synthetic non-steroidal oestrogen that was first synthesised in 1938 [13] and then prescribed to several million women between 1940 and 1971 to prevent threatened miscarriage in the first trimester [14], before untoward side effects stopped further prescription [15]. It has also been used to enhance fertility in farm animals used for meat supply [15].

-

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are stable man-made compounds that do not readily degrade and tend to persist in the environment and bioaccumulate [2•]. Many are lipophilic and therefore become stored in fatty tissues, passing up the food chain in animal fat. From use as an insecticide, both dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and its breakdown product dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) remain widely present in human adipose tissue [16] and are endocrine disrupters [2•]. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are industrial POPs which are also widely measurable in human adipose tissue [17] and have been shown to be endocrine disrupters [2•].

-

Bisphenol A and phthalates are used in the manufacture of plastics. Bisphenol A (BPA) is used for its cross-linking properties in the manufacture of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, which are now ubiquitous in consumer products such as water bottles, linings of water pipes, coatings on food and beverage cans, thermal paper and dental sealants. It is listed as a high production volume chemical by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [18]. It can leach out from plastic containers [19] and has endocrine-disrupting properties [20, 21]. Phthalates are esters of phthalic acid and are used mainly as plasticizers to increase the flexibility, transparency and durability of plastic materials. They are found in many consumer products including adhesives, paints, packaging, children’s toys, electronics, flooring, medical equipment, personal care products, air fresheners, food products, pharmaceuticals and textiles. Many of the phthalates are also listed by the OECD in their 2004 list of high production volume chemicals [18] and possess endocrine-disrupting properties [22, 23].

-

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polybrominated biphenyls are widely used as flame retardants. They are now detectable in human tissues [24] and have endocrine-disrupting properties through interference in thyroid function [25].

-

4-Nonylphenol is one of the long-chain alkyl phenols used as a surfactant in industrial and domestic applications worldwide which is listed as a high production chemical by the OECD [18] and is an endocrine disrupter due to its estrogenic activity [26].

-

Parabens (alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid) are used as antimicrobial agents for the preservation of personal care products, foods, pharmaceutical products and paper products. They are widely present in human tissues including breast tissue and have estrogenic properties [27].

-

Phytoestrogens are produced naturally by plants and as such are ingested by humans in the diet in edible plant material. Isoflavones such as genistein and daidzein are found in soybeans, legumes, lentils and chickpeas. Phytoestrogens are so named for their estrogenic activity [28]. On the general assumption that naturally occurring compounds are more beneficial than synthetic compounds, phytoestrogens have been embraced much more positively by society than the synthetic xenoestrogens, and as such, potential benefits tend to have been overemphasised compared with adverse effects, such as those potentially related to obesity.

Developmental Susceptibility to Obesogenic EDCs

An especially sensitive time frame for exposure to obesogens has been found to be either prior to birth in utero or in the neonatal period [29]. Animal models have shown that exposure of pregnant mice to TBT results in offspring which are heavier than those not exposed [30]. Neonatal mice exposed to the synthetic oestrogen DES have also been reported to have increased body weight [31]. Figure 2 shows a representative photomicrograph at 4–6 months of age of control and neonatal DES-treated female mice: the mice were treated on days 1–5 of age with 1 μgDES/kg body weight/day, and obesity was evident by 4–6 months of age [31]. This serves to demonstrate the obesogenic consequences of exposure to a potent oestrogen at an inappropriate developmental stage. Other animal models have shown that exposure to some PCB congeners [32], to BPA [33], to bisphenol S, an increasingly used substitute for BPA [34•], and to a commercial mixture of PBDEs [35] can also predispose animals to weight gain. Post-weaning exposure of C57BL/6J mice to methylparaben by oral gavage also increased adiposity [36•], but such effects were not observed with the longer alkyl chain butylparaben [36•]. This is in marked contrast to the positive association observed for parabens between oestrogenic activity and longer alkyl chains [27].

Exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) during the neonatal period predisposes to obesity in mice at 4–6 months of age. Reproduced from Newbold et al. [99], with permission from Elsevier

The reported rise in obesity of children under 2 years of age [37, 38] is also suggestive of alterations during development. It would seem unlikely that such young children would have been affected by eating so much more food and taking so much less exercise than in previous generations, and current explanations revolve around an altered environment in utero or postnatally which is affecting fat deposition in early life [4•]. This is backed by epidemiological evidence [39,40,41]. Studies of babies born to mothers who smoked tobacco during pregnancy have been found to have a low birth weight, but paradoxically to then be at increased risk of obesity [42], and meta-analysis of multiple studies confirms that early-life exposure to some components of tobacco smoke can lead to later obesity [43]. A study of children in the Faroe Islands has shown that prenatal exposure to PCBs and DDE contained in dietary seafood is also associated with increased body weight [44•]. Interestingly, the effects in this study showed a non-monotonic response with the lower doses causing a greater weight gain, an effect which is consistent with many other actions of the EDCs where non-monotonic responses are commonly observed [45]. Other studies have shown that early-life exposures to some POPs [46] and bisphenol A [47] are also associated with increased body weight in young children.

Some studies suggest that such effects may even be inherited through future generations without the need for further exposure. Transgenerational studies have shown that pregnant mice exposed to TBT produce offspring with greater fat deposits, and this phenotype was found to be passed on to the F3 generation, although there was no further TBT exposure [48•]. Other heritable traits towards obesity in rodents have been demonstrated following exposure to BPA and phthalates (diethylhexyl and dibutyl) [49•] and DDT [50•].

Mechanisms of Action of Obesogenic EDCs

Obesogens cause weight gain by altering lipid homeostasis to promote adipogenesis and lipid accumulation, and this may occur through multiple mechanisms, outlined in Fig. 3. This may occur through increasing the number of adipocytes, increasing the size of adipocytes or altering the endocrine pathways responsible for the control of adipose tissue development. In general, early developmental changes (in utero or postnatally) involve an increase in adipocyte numbers, whilst changes later in life during adulthood tend to involve mainly an increase in the size of adipocytes [51]. Current evidence suggests that adipocyte numbers are set by the end of childhood and that any increase in adipocyte numbers in early life tends to be permanent [51]. This has profound consequences for the timing of exposure to obesogens, implying that alterations during early life would be passed on into adulthood, which would not be reversed [4•]. Other mechanisms of interference by obesogens may involve altering hormones that regulate appetite, satiety and food preferences, altering the basal metabolic rate or altering the energy balance to favour storage of calories. Finally, mechanisms may involve alterations to insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism in endocrine tissues such as the pancreas, adipose tissue, liver, gastrointestinal tract, brain or muscle.

At a molecular level, obesogens can act by interfering with nuclear transcriptional regulators that control lipid flux and/or adipocyte proliferation/differentiation, such as the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARα, PPAR-δ and PPAR-γ) and steroid hormone receptors. These receptors all function as ligand-activated transcription factors in that, after binding ligands, they are enabled to bind to response elements in the DNA and act to regulate specific patterns of gene expression [2•]. EDCs which can bind to these nuclear receptors have the potential to cause inappropriate responses, including obesity.

Obesogens Acting through Interference with PPARs

PPARs can bind a wide range of unsaturated fatty acids and therefore act as lipid sensors to regulate lipid homeostasis. PPARγ functions in energy storage through its regulatory actions on adipogenesis and has therefore been defined as a master regulator of fat cell development [52]. PPARs act by heterodimerisation with retinoid X receptors (RXRs), and activation of RXR-PPARγ favours the differentiation of adipocyte progenitors and preadipocytes in adipose tissue and regulates lipid biosynthesis and storage [53]. In contrast, activation of the RXR-PPARα heterodimer stimulates β-oxidation breakdown of fatty acids [54]. Several EDCs have now been shown to alter adipogenesis through interfering in PPARγ actions [55].

Both tributyltin and triphenyltin are nanomolar affinity ligands for the RXR-PPARγ heterodimer [30, 56] and stimulate 3T3-L1 preadipocytes to differentiate into adipocytes [30, 56, 57] in a PPARγ-dependent manner [58, 59]. Using the same 3T3L1 cell model, BPA [60], nonylphenol [61] and the fungicide triflumizole [62] have also been shown to promote adipogenesis. The phthalate metabolite mono(2-ethyl-hexyl)phthalate is a known potent and selective activator of PPARγ [63] that promotes the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells into adipocytes [64]. Although many phthalates show greater responses through PPARα than on PPARγ [65], it may be the metabolites which act through PPARγ that cause weight gain. Phthalate metabolites in excess of several micrograms per litre have been measured in over three quarters of urine samples from the US population [66], and epidemiological studies have noted an association between phthalate metabolites and increased waist circumference [67, 68]. More recent work has reported that benzyl butyl phthalate can promote adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes [69], and so there may be some variation between different esters.

Parabens have also been shown to promote adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells [70]. Adipogenic potency increased with the linear length of the alkyl chain [70] and was associated with PPARγ activation [71]. It now appears likely that any ligand which can bind to the PPARγ will be able to influence adipogenesis and obesity [71]. Since so many of such ligands are present in human adipose tissue, it is probable that they may also be able to act in combination through additive mechanisms. This may then enable mixtures of such ligands to stimulate adipogenesis at lower concentrations than needed for each alone. Such additive effects are recognised for other endocrine-disrupting mechanisms, most notably in the context of combinations of oestrogenic compounds acting via oestrogen receptors to increase proliferation of oestrogen-responsive cells [2•].

Obesogens Acting through Interference with Steroid Receptors

Steroid hormones can influence lipid storage and fat deposition and can therefore also impact on adipose tissue development [72]. Hormone replacement therapy based on oestrogens can protect against many age-related changes in adipose depot remodelling at menopause [73]. Dietary soy phytoestrogens, such as genistein and daidzein, modulate oestrogen receptor signalling and reverse truncal fat accumulation in postmenopausal women [74], an effect which has been demonstrated also in ovariectomized rodent models [75]. However, foetal or neonatal oestrogen exposure can have the opposite effect and lead to obesity later in life, which emphasises, again, that timing of exposure can be important in the consideration of outcomes. Rodents treated with phytoestrogens during pregnancy or lactation were observed to develop obesity at puberty [76], especially in males [77], which might question the wisdom of consumption of soy-based products by baby boys. Neonatal exposure of female mice to the synthetic oestrogen DES initially led to depressed body weight, but was followed by long-term weight gain in adulthood [78, 79], although notably not in male mice [80], demonstrating the obesogenic effect of a potent oestrogen on adipogenesis which can be gender-specific.

Whilst some EDCs may act directly through cellular steroid receptors, other EDCs may act less directly by stimulating oestrogen synthesis. Adipose tissue is known to be a site of oestrogen synthesis, and the cytoplasm of adipocytes contains the cytochrome P450 enzyme aromatase which converts testosterone to oestrogens. Several EDCs are now known to be able to influence intracellular aromatase activity [81] and could therefore act indirectly to raise the intracellular levels of oestrogen in adipocytes with a consequent increase in obesity not only in women but also in men [82].

Obesogens Act through Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptors

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that senses the presence of foreign compounds such as POPs and leads to the activation of cytochrome P450 enzymes needed for their clearance from the body [2•]. However, AhR can indirectly influence adipogenesis through altering PPARγ expression, and some POPs with obesogenic activity, which can be inhibited by AhR antagonists, have been suggested to function through this mechanism of action [32].

Obesogens Act by Altering Recruitment of Fat Cells

Mature adipocytes are generated from multipotent stromal cells (MSCs) of foetal and adult tissues [83]. These MSCs can differentiate into several different cell types in vitro, including not only adipose tissue but also bone, cartilage and muscle, and regulation of these processes is essential for homeostasis. Exposure of pregnant mice to TBT has been shown to result in MSCs which differentiate in offspring preferentially into adipocytes rather than bone and, furthermore, which have epigenetic alterations in the methylation status of some adipogenic genes [58]. Similar results were obtained following prenatal exposure to the fungicide triflumizole [62], which demonstrates that some EDCs can act by altering recruitment as well as differentiation of fat cells. A sensitive time for such alterations would be during the development of adipose tissue in early life.

Obesogens act by altering appetite, satiety and food preferences

Another mechanism of EDC action may be through altering the energy balance between energy intake and energy expenditure, especially by altering appetite, satiety and food preferences. Although BPA has been shown to induce obesity in experimental studies [33] and is present in over 90% of urine samples in the US population [84], no direct association has been established between serum BPA levels and amount of body fat [85]. However, more recently, BPA levels have been found to correlate in humans with circulating levels of leptin and ghrelin [86•]. These are hormones secreted by the adipose tissue which act in opposing ways to regulate hunger, with leptin being inhibitory and ghrelin being stimulatory. Alterations to the circulating levels of these hormones suggest that BPA may be able to act by interfering with hormonal control of hunger and satiety [86•], which is corroborated by a recent report of increased production of leptin mRNA in a 3T3L1 adipocyte model after 3 weeks of exposure to 1 nM BPA [87]. In a mouse model, post-weaning exposure to methylparaben also increased serum leptin levels [36•], which begs the question as to whether any association between paraben exposure and leptin levels might be observed in human studies.

The Vicious Spiral of Obesogenic EDC Actions and Human Health

Obesity is not just a matter of carrying excess weight through life, but has been established as an underlying risk factor for many diseases including metabolic syndrome [88], diabetes [89], cardiovascular disease [90] and cancer [91]. Coincidentally, development of many of these diseases has also been linked to exposure to EDCs [2•]. In this context, it is noteworthy that many EDCs are lipophilic, and POPs in particular are known to bioaccumulate in body fat over the years. It is therefore plausible that the link of obesity to disease relates not just simply to the deposition of fat but to the increased retention of lipophilic pollutants in the greater volume of fat. Figure 4 illustrates the potential for a “vicious spiral” to be set up whereby obesogens act to increase the amount of fat stored (be it by increased cell volume or increased cell number), which would be followed by greater retention of lipophilic obesogens and which would then lead onward in an increasing spiral of greater body fat and even more lipophilic pollutant retention. In this sense, obesogens may be self-fulfilling and be able to increase capacity for their own retention.

The “vicious spiral” of obesogenic activity and lipophilic properties of endocrine disruptors. The obesogenic activity of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) results in increased body fat: since EDCs are lipophilic, more EDCs will be stored as the amount of body fat increases. This may cause an upwards spiral towards increasing body fat and, therefore, increasing body burden of EDCs, and indeed of other lipophilic environmental pollutant chemicals as well

Although such a mechanism may enable obesity to be associated with a greater body burden of obesogens, there are also many other lipophilic pollutant chemicals which have adverse effects on the human body other than through their obesogenic activity. Therefore, the obesogenic nature of some EDCs may enable increased storage of a wide range of other lipophilic environmental pollutants with adverse properties, including non-obesogenic EDCs and non-obesogenic non-EDC environmental chemicals. Retention of such a complex mixture of pollutant chemicals offers the potential for additive or complementary mechanisms to aggravate disease processes. For example, in considering the hallmarks of cancer [92], whilst sustained proliferation of endocrine-regulated cancers may be driven by EDCs, other environmental chemicals may be needed to drive other cancer hallmarks, and genotoxic chemicals will be needed to cause the underlying mutations and genomic instability associated with cancer cells. For these reasons, the obesogenic activity of EDCs may have an even wider impact on disease processes than currently accredited.

One caveat is that the biological availability of the retained compounds in the fatty tissues/cells remains poorly understood. Whilst it is often assumed that xenobiotics retained in fatty deposits of the body would be sequestered, some xenobiotics are known to form fatty acid conjugates which themselves exert local toxicities [93]. Conjugate formation is a metabolic mechanism used to increase hydrophilicity to aid elimination from the body. Common conjugates are with sulphate, glucuronic acid, glutathione or amino acids, and this is also often assumed to negate biological activity. However, for phytoestrogens, whilst sulphation of some does negate oestrogenic activity, sulphation of others can enhance oestrogenic activity [94], and some glucuronide conjugates also retain oestrogenic activity [95]. Although BPA-glucuronide lacks oestrogenic activity, it has been reported as still capable of promoting adipogenesis [96]. The biological availability of pollutants retained in fat is therefore an unresolved aspect which needs further research and specific research to take account not only of enzymatic deconjugation to the free form but also the activity of conjugates themselves.

A further consideration is of the consequence of the timing of exposure to the obesogenic EDCs. Since obesogen exposure in utero or during early postnatal life can increase fat cell number permanently into adult life [4•, 51], it follows that early-life exposure to obesogens could result in a greater lifetime burden of lipophilic pollutants. Whilst the release of lipophilic pollutants in breast milk fat during breastfeeding may serve to detoxify the mother’s breasts, adverse consequences for the baby have long been a concern [97, 98]. However, sudden weight loss, such as through dieting, could also cause the release of lifetime bioaccumulated pollutants from body fat with untoward consequences if the release were too fast for the body to eliminate the compounds sufficiently quickly. A final unanswered question relates to whether pollutant retention may relate to body fat composition as well as quantity of body fat, and therefore whether there may be different consequences arising not just from variations in exposure to EDCs by differing lifestyles but also from variations in the retention of EDCs according to the specific fat composition laid down in the adipocytes.

Conclusions and Implications for Risk Assessment of Obesogenic EDCs

The weight of evidence pointing towards a role for EDCs in influencing obesity offers not just a mechanistic understanding of the obesity crisis but also a strategy for prevention. Although, undoubtedly, overeating coupled with lack of exercise is a major contributor to the rise in obesity, which can be resolved by reduced calorie intake and increased exercise, it may be that reduction in exposure to obesogenic EDCs, particularly during early life stages, could also contribute to reducing obesity in the population. This will require a political will to limit the use of some of the offending chemicals and an education programme in maternity clinics so that there is a more general understanding of the consequences of exposure to obesogens in early life. Although many of these EDCs were originally developed for a range of beneficial uses, their potential for contributing to obesity needs now to be added into risk assessment of EDCs, and the widespread exposure of the human population to so many EDCs with obesogenic activity requires assessment of the effects not only of individual chemicals but of the complex mixtures entering human tissues from varied lifestyle choices. However, perhaps one of the benefits of this research and its widespread dissemination in the popular media is that informed individuals can also act on a precautionary principle to reduce exposure of themselves and their children ahead of any regulatory actions and therefore have some degree of self-determination in their own exposure to such EDCs.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2548–56.

• Darbre PD. Endocrine disruption and human health. New York: Academic; 2015. Overview of EDCs and human health which sets the bigger picture.

• Heindel JJ, Schug TT. The obesogen hypothesis: current status and implications for human health. Curr Environ Health Rpt. 2014;1:333–40. Recent review of obesogens.

• Janesick AS, Blumberg B. Obesogens: an emerging threat to public health. Am J Ob Gynecol. 2016;214:559–65. Recent review of obesogens.

Nappi F, Barrea L, DiSomma C, et al. Endocrine aspects of environmental “obesogen” pollutants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:765. Recent review of obesogens.

Grun F, Blumberg B. Environmental obesogens: organotins and endocrine disruption via nuclear receptor signalling. Endocrinol. 2006;147 Suppl 6:S50–5.

• Heindel JJ, vom Saal FS, Blumberg B, et al. Parma consensus statement on metabolic disruptors. Environ Health. 2015;14:54. Proposal to broaden the definition of obesogens to include metabolic disruptors.

• OECD. Obesity update. June 2014. .www.oecd.org/health/obesity-update.htm. Accessed 8 Feb 2017. Statistics showing the rise in obesity.

Report of the Proceedings of the European workshop on the impact of endocrine disrupters on human health and wildlife. Weybridge, UK. Report EUR17549 of the Environment and Climate Change Research Programme of DGXII of the European Commission. 1996.

Horiguchi T. Masculinization of female gastropod mollusks induced by organotin compounds, focusing on mechanism of actions of tributyltin and triphenyltin for development of imposex. Environ Sci. 2006;13:77–87.

Saitoh M, Yanase T, Morinaga H, et al. Tributyltin or triphenyltin inhibits aromatase activity in the human granulosa-like tumor cell line KGN. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289:198–204.

Cooke GM. Effect of organotins on human aromatase activity in vitro. Toxicol Lett. 2002;126:121–30.

Dodds EC, Goldberg L, Lawson W, Robinson R. Estrogenic activity of certain synthetic compounds. Nature. 1938;141:247–8.

Smith OW. Diethylstilboestrol in the prevention and treatment of complications of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1948;56:821–34.

Harris RM, Waring RH. Diethylstilboestrol—a long-term legacy. Maturitas. 2012;72:108–12.

World Health Organisation. DDT and its derivatives. Environmental Health Criteria 1979; Number 9.

World Health Organisation. Polychlorinated biphenyls and terphenyls. Environmental Health Criteria 1992; Number 140.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). The 2004 OECD list of high production volume chemicals. Environment Directorate, Paris; 2004.

Krishnan AV, Stathis P, Permuth SF, et al. Bisphenol-A: an estrogenic substance is released from polycarbonate flasks during autoclaving. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2279–86.

Rubin BS. Bisphenol A: an endocrine disruptor with widespread exposure and multiple effects. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;127:27–34.

Rochester JR. Bisphenol A, and human health: a review of the literature. Reprod Toxicol. 2013;42:132–55.

Kamrin MA. Phthalate risks, phthalate regulation and public health: a review. J Toxicol Environ Health Part B. 2009;12:157–74.

Huang PC, Liou SH, Ho IK, et al. Phthalates exposure and endocrinal effects: an epidemiological review. J Food Drug Anal. 2012;20:719–33.

Bramwell L, Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, et al. Associations between human exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardant via diet and indoor dust, and internal dose: a systematic review. Environ Int. 2016;92–93:680–94.

Hallgren S et al. Effects of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on thyroid hormone and vitamin A levels in rats and mice. Arch Toxicol. 2001;75:200–8.

White R, Jobling S, Hoare SA, et al. Environmentally persistent alkylphenolic compounds are estrogenic. Endocrinology. 1994;135:175–82.

Darbre PD, Harvey PW. Parabens can enable hallmarks and characteristics of cancer in human breast epithelial cells: a review of the literature with reference to new exposure data and regulatory status. J Appl Toxicol. 2014;34:925–38.

Woods HF (Chairman). Phytoestrogens and health. Crown copyright, UK; 2003.

Janesick A, Blumberg B. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and the developmental programming of adipogenesis and obesity. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2011;93:34–50.

Grün F, Watanabe H, Zamanian Z, et al. Endocrine-disrupting organotin compounds are potent inducers of adipogenesis in vertebrates. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2141–55.

Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Snyder RJ, Jefferson WN. Developmental exposure to estrogenic compounds and obesity. Birth Defects Res Part A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73:478–80.

Arsenescu V, Arsenscu RI, King V, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyl-77 induces adipocyte differentiation and proinflammatory adipokines and promotes obesity and atherosclerosis. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:761–8.

vom Saal FS, Nagel SC, Coe BL, et al. The estrogenic endocrine disrupting chemical bisphenol A (BPA) and obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;354:74–84.

• Ivry Del Moral L, LeCorre L, Poirier H, et al. Obesogen effects after perinatal exposure of 4,4′-sulfonyldiphenol (bisphenol S) in C57BL/6 mice. Toxicology. 2016;357–358:11–20. Paper reporting that commercial substitutes are not always without obesogenic activity.

Patisaul HB et al. Accumulation and endocrine disrupting effects of the flame retardant mixture Firemaster® 550 in rats: an exploratory assessment. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2013;27:124–36.

• Hu P, Kennedy RC, Chen X, et al. Differential effects on adiposity and serum marker of bone formation by post-weaning exposure to methylparaben and butylparaben. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23:21957–68. Paper demonstrating that parabens are also obesogens.

Kim J et al. Trends in overweight from 1980 through 2001 among preschool-aged children enrolled in a health maintenance organization. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1107–12.

Koebrick C, Smith N, Coleman KJ, et al. Prevalence of extreme obesity in a multi-ethnic cohort of children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2010;157:26–31.e2.

Verhulst SL, Nelen V, Hond ED, et al. Intrauterine exposure to environmental pollutants and body mass index during the first 3 years of life. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:122–6.

Heindel JJ. The obesogen hypothesis of obesity: overview and human evidence. In: Lustig RH, editor. Obesity before birth: maternal and prenatal influences on the offspring. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 355–365.

LaMerrill M, Birnbaum LS. Childhood obesity and environmental chemicals. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78:22–48.

Power C, Jefferis BJ. Fetal environment and subsequent obesity: a study of maternal smoking. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:413–9.

Oken E, Levitan EB, Gillman MW. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and child overweight: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2008;32:201–10.

• Tang-Peronard JL et al. Association between prenatal polychlorinated biphenyl exposure and obesity development at ages 5 and 7 years: a prospective cohort study of 656 children from the Faroe Islands. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:5–13. Non-monotonic responses to obesogens.

Vandenberg LN, Colborn T, Hayes TB, et al. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocr Rev. 2012;33:378–455.

Tang-Peronard JL, Andersen HR, Jensen TK, Heitmann BL. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and obesity development in humans: a review. Obes Rev. 2011;12:622–36.

Vafeiadi M, Roumeliotaki T, Myridakis A, et al. Association of early life exposure to bisphenol A with obesity and cardiometabolic traits in childhood. Environ Res. 2016;146:379–87.

• Chamorro-Garcia R, Sahu M, Abbey RJ, Laude J, Pham N, Blumberg B. Transgenerational inheritance of increased fat depot size, stem cell reprogramming, and hepatic steatosis elicited by prenatal exposure to the obesogen tributyltin in mice. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:359–66. Evidence for transgenerational effects.

• Manikkam M, Tracey R, Guerrero-Bosagna C, Skinner MK. Plastics derived endocrine disruptors (BPA, DEHP and DBP) induce epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of obesity, reproductive disease and sperm epimutations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55387. Evidence for transgenerational effects.

• Skinner MK, Manikkam M, Tracey R, et al. Ancestral dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) exposure promotes epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of obesity. BMC Med. 2013;11:228. Evidence for transgenerational effects.

Spalding KL, Arner E, Westermark PO, et al. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature. 2008;453:783–7.

Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79:1147–56.

Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, et al. PPARγ is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4:611–7.

Ferre P. The biology of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: relationship with lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2004;53 Suppl 1:S43–50.

Janesick A, Blumberg B. Minireview: PPARγ as the target of obesogens. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;127:4–8.

Kanayama T, Kobayashi N, Mamiya S, et al. Organotin compounds promote adipocyte differentiation as agonists of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma/retinoid X receptor pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:766–74.

Inadera H, Shimomura A. Environmental chemical tributyltin augments adipocyte differentiation. Toxicol Lett. 2005;159:226–34.

Kirchner S, Kieu T, Chow C, et al. Prenatal exposure to the environmental obesogen tributyltin predisposes multipotent stem cells to become adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:526–39.

Li X, Ycaza J, Blumberg B. The environmental obesogen tributyltin chloride acts via peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma to induce adipogenesis in murine 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;127:9–15.

Masuno H, Kidani T, Sekiya K, et al. Bisphenol A in combination with insulin can accelerate the conversion of 3T3-L1 fibroblasts to adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:676–84.

Masuno H, Okamoto S, Iwanami J, et al. Effect of 4-nonylphenol on cell proliferation and adipocyte formation in cultures of fully differentiated 3T3-L1 cells. Toxicol Sci. 2003;75:314–20.

Li X, Pham HT, Janesick AS, Blumberg B. Triflumizole is an obesogen in mice that acts through peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1720–6.

Maloney EK, Waxman DJ. Trans-activation of PPARγ and PPARγ by structurally diverse environmental chemicals. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;161:209–18.

Feige JN, Gelman L, Rossi D, et al. The endocrine disruptor monoethyl-hexyl-phthalate is a selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ modulator that promotes adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19152–66.

Hurst CH, Waxman DJ. Activation of PPARγ and PPARγ by environmental phthalate monoesters. Toxicol Sci. 2003;74:297–308.

Silva MJ, Barr DB, Reidy JA, et al. Urinary levels of seven phthalate metabolites in the U.S. population from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2000. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:331–8.

Stahlhut RW, van Wijngaarden E, Dye TD, et al. Concentrations of urinary phthalate metabolites are associated with increased waist circumference and insulin resistance in adult U.S. males. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:876–82.

Hatch EE, Nelson JW, Qureshi MM, et al. Association of urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations with body mass index and waist circumference: a cross-sectional study of NHANES data, 1999–2002. Environ Health. 2008;7:27.

Yin L, Yu KS, Lu K, Yu X. Benzyl butyl phthalate promotes adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes: a high content cellomics and metabolomics analysis. Toxicol In Vitro. 2016;32:297–309.

Hu P, Chen X, Whitener RJ, et al. Effects of parabens on adipocyte differentiation. Toxicol Sci. 2013;131:56–70.

Pereira-Fernandes A, Demaegdt H, Vandermeiren K, et al. Evaluation of a screening system for obesogenic compounds: screening of endocrine disrupting compounds and evaluation of the PPAR dependency of the effect. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77481.

Law J, Bloor I, Budge H, Symonds ME. The influence of sex steroids on adipose tissue growth and function. Horm Mol Biol Clin Invest. 2014;19:13–24.

Haarbo J, Marslew U, Gotfredsen A, Christiansen C. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy prevents central distribution of body fat after menopause. Metabolism. 1991;40:1323–6.

Wu J, Oka J, Tabata I, et al. Effects of isoflavone and exercise on BMD and fat mass in postmenopausal Japanese women: a 1-year randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:780–9.

Kim HK, Nelson-Dooley C, Della-Fera MA, et al. Genistein decreases food intake, body weight, and fat pad weight and causes adipose tissue apoptosis in ovariectomized female mice. J Nutr. 2006;136:409–14.

Ruhlen RL, Howdeshell KL, Mao J, et al. Low phytoestrogen levels in feed increase fetal serum estradiol resulting in the “fetal estrogenization syndrome” and obesity in CD-1 mice. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:322–8.

Penza M, Montani C, Romani A, et al. Genistein affects adipose tissue deposition in a dose-dependent and gender-specific manner. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5740–51.

Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Jefferson WN. Adverse effects of the model environmental estrogen diethylstilbestrol are transmitted to subsequent generations. Endocrinology. 2006;147 Suppl 6:S11–7.

Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Snyder RJ, Jefferson WN. Perinatal exposure to environmental estrogens and the development of obesity. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:912–7.

Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Jefferson WN, Heindel JJ. Effects of endocrine disruptors on obesity. Int J Androl. 2008;31:201–8.

Whitehead SA, Rice S. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals as modulators of sex steroid synthesis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20:45–61.

Williams G. Aromatase up-regulation, insulin and raised intracellular oestrogens in men, induce adiposity, metabolic syndrome and prostate disease, via aberrant ER-α and GPER signalling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;351:269–78.

da Silva ML, Caplan AI, Nardi NB. In search of the in vivo identity of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2287–99.

Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, et al. Exposure of the U.S. population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003–2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:39–44.

Oppeneer SJ, Robien K. Bisphenol A exposure and associations with obesity among adults: a critical review. Public Health Nutr. 2014;14:1–17.

• Rönn M, Lind L, Örberg J, et al. Bisphenol A is related to circulating levels of adiponectin, leptin and ghrelin, but not to fat mass or fat distribution in humans. Chemosphere. 2014;112:42–8. A reported correlation between exposure to bisphenol A and levels of leptin and ghrelin, which now needs confirmation in experimental animal models.

Ariemma F, D’Esposito V, Liguoro D, et al. Low-dose bisphenol-A impairs adipogenesis and generates dysfunctional 3T3-L1 adipocytes. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150762.

NCEP ATP-III. Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421.

Ross SA, Dzida G, Vora J, et al. Impact of weight gain on outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1431–8.

Bastien M, Poirier P, Lemieux I, Després JP. Overview of epidemiology and contribution of obesity to cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;56:369–81.

Berger NA. Obesity and cancer pathogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2014;1311:57–76.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74.

Ansari GAS, Bhupendra S, Kaphalia M, et al. Fatty acid conjugates of xenobiotics. Toxicol Lett. 1995;75:1–17.

Pugazhendhi D, Watson KA, Mills S, et al. Effect of sulphation on the oestrogen agonist activity of the phytoestrogens genistein and daidzein in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J Endocrinol. 2008;197:503–15.

Zhang Y, Song TT, Cunnick JE, et al. Daidzein and genistein glucuronides in vitro are weakly estrogenic and activate human natural killer cells at nutritionally relevant concentrations. J Nutr. 1999;129:399–405.

Boucher JG, Boudreau A, Ahmed S, et al. In vitro effects of bisphenol A β-d-glucuronide (BPA-G) on adipogenesis in human and murine preadipocytes. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:1287–93.

Lehmann GM, Verner MA, Luukinen B, et al. Improving the risk assessment of lipophilic persistent environmental chemicals in breast milk. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2014;44:600–17.

Van den Berg M, Kypke K, Kotz A, et al. WHO/UNEP global surveys of PCDDs, PCDFs, PCBs and DDTs in human milk and benefit-risk evaluation of breastfeeding. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91:83–96.

Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Jefferson WN. Environmental estrogens and obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;304:84–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Philippa D. Darbre declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Etiology of Obesity

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Darbre, P.D. Endocrine Disruptors and Obesity. Curr Obes Rep 6, 18–27 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0240-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0240-4