Abstract

Caregiving for persons with dementia has been associated with exacerbated stress and burden that can impact the health and well-being of those providing care. Spouses and adult children are the majority of these caregivers and their needs and vulnerabilities often differ. In addition, ethnicity and race are also factors that can influence caregiver needs and responses. This paper reviews recent studies on caregiver well-being, relationships, and ethnicity and interventions that may support those in caregiving roles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is estimated that 70 % of the 4.5 million persons with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the United States live at home with family and friends providing 75 % of their care. This care can range from just a few hours a week to more than 117 h [1]. Caregiving for persons with AD is particularly demanding as the needs for care escalate with the progress of the disease. Thus, both the physical and mental health of caregivers are at risk as they become vulnerable to stress and depression which can contribute to negative health behaviors, such as neglecting preventive care or attending to personal health care needs [2, 3, 4•]. Because caregivers play such vital roles for persons with dementia, it is critical to understand the factors that affect their well-being and their caregiving roles. This article begins with a review of the many types of dementia and research on the many variables that can impact caregivers as well as interventions that can improve or enhance their quality of life.

Types of Dementia

Dementia involves the loss of memory and other mental abilities that interferes with the ability to perform the activities of daily life. These losses result from changes in the brain and are associated with various causes. Consequently, there are different types of dementia, including vascular dementia, Huntington’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease, Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia resulting from traumatic brain disease.

However, the most common type of dementia, accounting for 60–80 % of all cases, is that resulting from Alzheimer’s disease [5]. Alzheimer’s disease is a major public health problem; by the year 2050, it is estimated that 13.5 million individuals in the United States will manifest symptoms of AD.

Early symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) include difficulties remembering names and recent events, apathy, and depression. As the illness progresses symptoms include impaired judgment, disorientation, confusion, behavior changes, and difficulty speaking, swallowing and walking. These changes result from the deposits of beta-amyloid plaques, protein tangles in the brain. The illness is most common among persons 65 and older with the risk increasing with age and reaching nearly 50 % after age 85. Family history is a major risk factor with head trauma, cardiovascular health, and alcohol also possible contributors to the disease. The illness is also found in younger persons with approximately 4 % of those with AD younger than 65 years.

Research on the progression rate of AD shows considerable variability among patients. The average length of life from the time of diagnosis to death varies and can be 3 to 4 years if the person is over 80 when diagnosed to 10 years or more for younger persons. A 15-year study of 597 patients that began at the initial clinic visit, identified two groups, slow progressors and fast progressors [6•]. Overall, the slow group lived longest with a median survival rate from the initial visit of 4.7 years in comparison to 2.5 years for fast progressors. The results are viewed as important for clinical trials of drug treatments, for the development of biomarkers and for developing education for caregivers.

Facilitators of Caregiver Well-being

The bulk of care for persons with AD in the United States is provided by family members who receive little formal assistance [7]. Studies comparing caregiving spouses and adult children find that the illness can have particularly deleterious effects on the health and mental well-being of spouses who must deal with the daily stress associated with caregiving. This stress is exacerbated by the fact that they frequently have little respite from caregiving and must deal with the realization that they are losing a key intimate relationship in their lives [8, 9].

Coping, the ability to relieve the effects of a stressful situation by managing or reducing associated tension is particularly important in caregiving with successful coping associated with better reported health [10, 11]. Unfortunately, those caregivers with the highest anxiety and depression are more prone to use dysfunctional coping strategies such as disengagement than less anxious or depressed caregivers [12]. Among the many factors that may be related to coping is the meaning that caregivers give to caregiving. Those who are able to perceive it positively and as a means to spiritual growth are better able to transcend the difficulties and stresses that it entails [13]. These perspectives assist in decreasing feelings of burden and stress.

Other factors that can buffer the stress encountered by the caregiver are social supports [14], mastery, the ability to control factors affecting one’s life [15] and feelings of self-efficacy, the belief that one’s behaviors produce certain outcomes [16]. Helping caregivers to engage in techniques such as meditation and relaxation training can potentially increase their feeling of self-efficacy, i.e., to manage stress and/or burden. Assisting caregivers to manage their own upsetting thoughts, regardless of the burden they are experiencing, can lower their levels of distress, while teaching them how to control their thinking can reduce the negative responses that lead to stress [17•]. At the same time, individual assessments are critical in determining what specific aspects of caregiving to target for intervention, i.e., because they are most stressful to the individual.

Differences in Effects of Caregiving on Spouses and Adult Children

Studies on the impact or stress associated with caregiving by family members have highlighted the vulnerability of spouses, with some risks particularly high for husbands and others for wives who act as caregivers. Caregiving can contribute to their own cognitive decline [18•, 19, 20]. Research on married couples finds the risk of developing dementia, where one acts as caregiver, is six times greater than in those couples where there is no dementia with the incidence highest for husbands caring for wives [21] On-going research is seeking what variables, psychological and physical, may contribute to this increased risk of dementia among caregiving spouses.

Marital communication and interaction are important influences on relationship satisfaction. These influences can be severely impacted by dementia as the impaired partner becomes less able to effectively engage. Research, using both self-reports and observations of communication patterns between couples, found poor communication related to high depression scores in caregivers [22]. Women may be most vulnerable to declining interactions as the impact was greater on caregiving wives who showed more depression to this declining interaction than caregiving husbands. Thus, if wives do show cognitive declines, it may result from the depression that they experience as caregiver.

A study of over 500 spousal and adult children caregivers found that, for both groups of caregivers, problematic behaviors of the care recipient and the ways in which they are interpreted by the caregiver are significant predictors of burden and stress. Moreover, for each group these behaviors were strong predictors of nursing home placement [23]. The stress resulting from dealing with these behaviors increased the desire to institutionalize the relative. However, the predictors of stress varied between adult children and spouses. Adult children who perceived the care recipient’s behavior as manipulating or overly demanding were more likely to be interested in institutionalizing while the extent to which caregiving was perceived as causing anxiety or depression was a significant predictor for spouses. The authors conclude that all caregivers should benefit from interventions that assist them in coping with problematic behaviors. At the same time, adult children may require greater assistance in dealing with relationship burden while spouses could benefit most from assistance that reduces feelings of stress.

One set of factors that is critical in spousal caregiver well-being are feelings of mastery as they help to moderate the impact of stressors on depression. Consequently, interventions that help caregivers to improve their self-evaluations and convince them that they can handle difficult caregiving challenges can be protective of their own mental health [24, 25]. Interventions that provide them with specific skills and assist caregivers to perceive the positive aspects of their roles are important in mediating the burdens they may experience.

Ethnicity and Caregiving

Ethnicity and culture have been explored in their relationships to caregiver outcomes. with particular attention paid to the role of familism, the belief that families should provide care to their relatives, and cultural norms that dictate appropriate role behaviors [26]. Such values ay actually increase caregiver distress as families are reluctant to use formal supports [27] or to institutionalize [28]. It is important to recognize that familism is a multi-dimensional concept that has both positive and negative effects on caregivers. When the family is perceived as a strong source of support the influence is positive, but dysfunctional thoughts such as beliefs that one should never lose control or get angry may become barriers to coping [29].

Several studies have explored the relationship between race and caregiving status with many suggesting that black caregivers have an easier time adapting than white caregivers. Blacks are less likely to report feeling emotionally distressed or depressed [30] and more likely to report positive caregiving experiences in comparison to other racial groups [31]. A longitudinal study of racial differences in caregiver adaptation [32] found black caregivers declining in depressive symptoms over time while these emotions remained relatively stable for whites. Possible factors that may contribute to the ability of blacks to adjust more easily to the demands and stresses of caregiving include their religious involvement, availability of social supports and positive attitudes towards caregiving that diminish the perceived sense of burden that caregiving often entails.

A qualitative study utilizing focus groups found differences among ethnic groups with regards to a stigma associated with dementia. This stigma could affect caregivers’ willingness to seek assistance or to discuss the illness outside of the family. The findings suggest that African-American, Chinese-American and Hispanics are more likely to perceive the illness as a stigma with such beliefs seriously impeding the likelihood that they will seek advice or medical interventions [33].

Findings from the Duke Caregiver Study that included 87 intergenerational caregivers (50 white and 37 black) examined the ways in which living arrangements contribute to the stress of caregiving vary by race. Among intergenerational caregiving dyads, living together with the care recipient was most distressing for black caregivers while living apart was more distressing for whites [34]. Further research into these differences should help in uncovering the specific aspects of these arrangements, such as privacy and space, and how they may interact with other components of depression that impact caregivers’ stress

Communicating to care recipients that they are loved, respected, and worthy of special considerations has been explored in relation to ethnicity and caregiver outcomes [35]. Research indicates that such communication partially explains the differences between the subjective appraisals of caregivers and can contribute to the burdens they experience [36]. The research findings suggest that interventions to enhance such communication be targeted to specific groups. For example, White/Caucasian and Hispanic/Latino caregivers who may be less verbal in expressing their feelings may benefit from interventions that focus on ways to demonstrate respect for the care recipient, while Black/African American caregivers could benefit most from interventions that enhance their own positive emotional responses to their caregiving roles.

Studies on the role of religion and its possible support for caregivers indicate that its impact also varies among ethnic groups. Thus, greater subjective religiosity, importance of religion to the individual was related to increased health risk for white non-Hispanic caregivers. Among Latina caregivers, non-organizational religious coping, such as individual prayer, decreased their health risks [37]. For both groups, increased subjective religiosity was significantly associated with decreases in regular exercise, a positive health behavior

The relationship between religious coping, burden, depression, and race was studied among 211 African American, 220 White, and 211 Hispanic caregivers. Religious coping, the use of prayer, mediated burden and depression and was used most by African Americans [38]. Further research on the dimensions of religion and religious practices and the ways that they impact caregivers is needed if it is to be incorporated into the design of interventions.

Desire to Institutionalize

The decision to institutionalize a relative with dementia is generally a very difficult one for families. Most patients express a desire to remain at home and families attempt to adhere to this desire as long as possible. Research also indicates that cultural values and the ways in which caregiving are perceived may also be important influences on the decision to institutionalize [39].

At some point the need to institutionalize becomes a reality for many caregivers. Risk factors for institutionalization include caregiver stress [40], burden [41], the behaviors of the care recipient [42], and ethnicity [43]. A meta-review of 782 studies which examined factors predicting nursing home placement for persons with dementia found that the greater emotional stress of the caregivers, a desire to institutionalize, and feelings of being “trapped” in care responsibilities increased the likelihood of placement [44].

These findings are supported through a longitudinal study of over 5,000 caregivers which found that more than 40 % of the persons with dementia who, at baseline, were being cared for at home entered a nursing home during the 3-year study period [45•]. Both the burden experienced by the caregiver and the behavioral/psychiatric symptoms of the parent or spouse receiving care contributed to the institutionalization. This suggests that, if institutionalization is to be prevented or delayed, it is critical to deliver treatment simultaneously to both the caregiver and the parent or spouse with dementia.

The quality of the relationship which may be defined as the degree of warmth and conflict between the caregiver and the parent or spouse with dementia is important in nursing home placement. Findings from some studies suggest that male caregivers may be more influenced by the quality than women and thus more ready to institutionalize when they perceive the quality as poor [46•]. Reasons for the differences between the genders are not clear but it may be that women are more accustomed to the caregiving role and more accepting of it.

Promising Interventions

New technology appears to have direct benefits for caregivers as it helps to reduce the stress and burden they experience. Internet technology that includes use of computers for easy access to professionals and other caregivers through support groups is promising [47•]. However, caregivers are also likely to require much assistance in learning how to use the internet and such modalities as chat rooms or downloading streaming videos. Recruitment to these new types of supportive services is often difficult as caregivers frequently feel unable to commit to the demands of learning a new technological program. However, once enrolled, they tend to find them supportive.

Assistive technology can also be supportive of caregivers. Mobility monitors and tracking systems can be helpful in reducing wandering and thus relieve worries for caregivers. The transmitter on the ankle or wrist triggers an alert that is sent to the caregiver if the person goes outside of a specific range. Identification bracelets with the diagnosis and a 24-hour hotline number if the person wanders also ease the stress on caregivers.

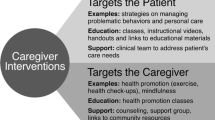

Finally, a systematic review of over 685 articles on studies that explored the effectiveness of interventions for caregivers of persons with dementia concluded that well-designed multi-component interventions can be effective in reducing caregiver burden and depression. Involving the person with dementia as well as the caregiver, encouraging active participation in educational interventions for caregivers, offering individualized rather than group session, and targeting the reduction of specific behaviors in the care recipient had the most positive caregiver outcomes [48].

Conclusions

The majority of caregiving to persons with dementia continues to be given by the family with most of these caregivers being the spouse or the adult child. Both of these groups are vulnerable to feelings of burden and stress that can impact their own well-being and their willingness to continue in the caregiving role. The responses of the caregiver may also be influenced by their gender, ethnicity, and race and even their living arrangements. Studies reviewed reflect the complexity of the caregiving relationships and the difficulties involved in understanding how a particular caregiver may respond. Personality, self-efficacy, feelings of mastery, quality of relationship and responses to stress are all important considerations in determining how best to address caregiver vulnerabilities and needs. Being able to accurately assess these factors at the individual level is necessary to ensure that that appropriate interventions are offered. At the same time, heterogeneity among caregivers necessitates the availability of a multitude of interventions that can be selected and customized for unique needs and situations.

New technologies and assistive devices hold the promise of being supportive to caregivers although special efforts are necessary to increase the acceptability and utilization of such technologies. Further research into the factors that increase caregivers’ willingness to accept new interventions and ways of educating them about their use may be important factors in helping to reduce caregiver burden and stress.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Elliott A, Burgio L, DeCoster J. Enhancing caregiver health: findings from the resources for enhancing Alzheimer’s caregiver health II intervention. JAGS. 2010;58(1):30–8.

Haley W, Gitlin L, Wisniewski S. Well-being, appraisal, and coping in African-American and caucasian dementia caregivers: findings from the REACH study. Gerontologist. 2004;37:355–64.

Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and non caregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–67.

• Smith G, Williamson G, Miller L, et al. Depression and quality of informal care: a longitudinal investigation of caregiver stressors. Psychol Aging. 2011;26(3):584–91. This study investigated longitudinal associations between caregiving stressors and quality of care in a sample of 213 caregivers. Increases in stressors over time led to increased depression with the increased depression leading to increases in potentially harmful behavior. The longitudinal study extends findings of cross-cultural research with indications for quality of care.

• Doody R, PavlikV, Massman P et al. Predicting progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2010; 22, http://alzres.com/content/2/1/2. Being able to predict the prognosis of AD and its progression is important for the design of clinical trials and also for assisting caregivers. Findings from 597 AD patients from initial visit to follow-up show different rates of progression. Using the baseline measure, clinicians should be able to predict performance over time on cognition, global performance and activities of daily living as well as survival length.

Widera E, Covinsky K. Fulfilling our obligation to the caregiver: it’s time for action, Comment on Translation of a dementia caregiver support program in a health care system-REACH VA. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):359–60.

Savundranqyagam M, Hummert M, Montgomery R. Investigating the effects of communication problems on caregiver burden. J Gerontol B, Psychol Soc Sci. 2005;60(1):S48–55.

Braun M, Scholz U, Bailey B, et al. Dementia caregiving in spousal relationships: a dyadic perspective. Aging Mental Health. 2009;13(3):426–36.

Sorensen S, Conwell Y. Issues in dementia caregiving: effects on mental and physical health, intervention strategies, and research needs. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;19(6):491–6.

Cooper C, Katona C, Orrell M, Livingston G. Coping strategies, anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23(9):929–36.

Garcia-Alzerca J, Cruz B, Lara J. Disengagement coping partially mediates the relationship between caregiver burden and anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Results from the MALAO-AD study. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):848–56.

Quinn C, Clare L, Woods R. The impact of motivation and meanings on the wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:43–55.

Gottleib B, Rooney J. Coping effectiveness: determinants and relevance to the mental health and affect of family caregivers of persons with dementia. Aging Mental Health. 2004;8:364–73.

Wilks S, Croom B. Perceived stress and resilience in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers: testing moderation and mediation models of social support. Aging Mental Health. 2008;12(3):357–65.

Rabinowiz Y, Mausbach B, Thompson L, Gallagher-Thompson D. The relationship between self-efficacy and cumulative health risk associated with health behavior patterns in female caregivers of elderly relatives with Alzheimer’s dementia. J Aging Health. 2007;19(6):946–64.

• Romero-Moreno A, Losada B, Mausbach M, et al. Analysis of the moderating effect of self-efficacy domains in different points of the dementia caregiving process. Aging Mental Health. 2011;14(2):221–31. This study analyzed the moderating effect of self-efficacy on burden and upsetting thoughts in caregivers. Self-efficacy for controlling upsetting thoughts may be particularly effective for caregivers who report high burden scores, attenuating the impact of burden on caregivers’ distress (depression and anxiety).

• Savundranayagam M, Montgomery R, Kosloski K. A dimensional analysis of caregiver burden among spouses and adult children. Gerontologist. 2011;51(3):321–31. A study of burden in 280 spouse and 243 adult child caregivers found that stress burden among spouses and relationship burden among adult children were significantly linked with intention to institutionalize. The findings indicate the practice implications of meeting the needs of the two groups of caregivers.

Caswell L, Vitaliano P, Croyle K, et al. Negative associations of chronic stress and cognitive performance in older spouse caregivers. Exp Aging Res. 2003;2:303–18.

Lee, Kawachi I, Goodstein E. Does caregiving stress affect cognitive function in older women? J Nerv Mental Disord. 2004;192:51–7.

Norton M, Smith K, Ostbye T, et al. Greater risk of dementia when spouse has dementia? Cache County Study, JAGS. 2010;58:895–900.

Braun M, Scholz U, Hornung R, Martin M. The burden of spousal caregiving: a preliminary psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging Mental Health. 2010;14(2):159–67.

Savundranayagam M, Montgomery R, Kosloski K. A dimensional analysis of caregiver burden among spouses and adult children. Gerontologist. 2011;51(3):321–31.

Pioli M. Global and caregiving mastery as moderators in the caregiving stress process. Aging Mental Health. 2010;14(5):603–12.

McLennon S, Habermann B, Rice M. Finding meaning as a mediator of burden on the health of spouses with dementia. Aging Mental Health. 2011;15(4):522–30.

Losada A, Shurgot G, Knight B, et al. Cross-cultural study comparing the association of familism with burden and depressive symptoms in two samples of Hispanic dementia caregivers. Aging Mental Health. 2006;10:69–76.

Cox C. Service needs and use: a further look at the experiences of African American and white caregivers seeking Alzheimer’s assistance. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis. 1999;14(2):93–101.

Scharlach A, Kellam R, Ong N, et al. Cultural attitudes and caregiver service use: lessons from focus groups with racially and ethnically diverse family caregivers. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2006;47:133–56.

Losada A, Marquez-Gonzalea M, Knight B, et al. Psychosocial factors and caregiver’s distress: effects of familism and dysfunctional thoughts. Aging Mental Health. 2010;14(2):193–202.

Cox C. Meeting the mental health needs of the caregiver: the impact of Alzheimer’s disease on Hispanic and African American families. In: Padgett DK, editor. Handbook on ethnicity, aging, and mental health. Westport: Greenwood Press; 1995. p. 265–83.

Roff L, Burgio L, Gitlin L. Positive aspects of Alzheimere’s caregiving: the role of race. J Gerontol B Psychol Soc Sci. 2004;59(4):185–90.

Sharupski K, McCann J, Bienieas J, Evans D. Race differences in emotional adaptation of family caregivers. Aging Mental Health. 2009;13(5):715–24.

Vickery B, Strickland T, Fitten L, et al. Ethnic variations in dementia caregiving experiences: insights from focus groups. J Human Behav Soc Environ. 2007;15(2/3):233–349.

Siegler I, Brummett B, Williams R, et al. Caregiving, residence, race, and depressive symptoms. Aging Mental Health. 2010;14(7):771–8.

Dooley W, Shaffer D, Lance C, et al. Informal care can be better than adequate: development and evaluation of the Exemplary Care Scale. Rehabil Psychol. 2007;52(4):359–69.

Harris G, Durkin D, Allen R, et al. Exemplary care as a mediator of the effects of caregiver subjective appraisal and emotional outcomes. Gerontologist. 2011;51(3):332–42.

Rabinowitz Y, Mausbach B, Atkinson P, Gallagher-Thompson D. The relationship between religiousity and health behaviors in female caregivers of older adults with dementia. Aging Mental Health. 2009;13(6):788–98.

Heo G, and Koeske G. The role of religious coping and race in Alzheimer’s disease caregiving. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2012. 0733464811433484, first published on March 22, 2012 as doi:10.1177/0733464811433484

Mausbach B, Coon D, Depp C, et al. Ethnicity and time to institionalization of dementia paitnts: a comparison of Latina and Caucasian female family caregiver. JAGS. 2004;S2:1077–84.

Spillman B, Long S. Does high caregiver stress predict nursing home entry? Inquiry. 2009;46:140–61.

Mittleman M, Haley W, Clay O, et al. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2006;67:159201599.

Spitznagel M, Tremont G, Dais J, et al. Psychosocial predictors of dementia caregiver desire to institutionalize: caregiver, care recipient, and family relationship factors. J Geriatric Psychiatry Neurol. 2006;19:16–20.

Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients and dementia. JAMA. 2002;287:2090–7.

Gaugler J, Krichbaum, Wyman J. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care. 2009;47:191–8.

• Gaugler J, Wall M, Kane R, et al. Does caregiver burden mediate the effects of behavioral distrubances on nursing home admission. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;19(6):497–506. Using secondary data from the Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration, data were collected from a sample of 5, 831 dementia caregivers. Over a 3 year period, almost 44 % of the persons with dementia entered a nursing home. The pathway to the nursing home is complex and there is a need for dual treatment of both caregivers and the person with dementia.

• Winter L, Gitlin L, Dennis M. Desire to institutionalize a relative with dementia: quality of of premorbid relationship and caregiver gender. Fam Relat. 2011;60:221–30. The quality of the relationship between individuals with dementia and their family caregivers has an impact on important clinical outcomes for both. Using a sample of 237 caregivers the findings revealed that quality of relationship was an important predictor of placement for male but not for female caregivers.

• Hayden L, Glynn S, Hahn T, et al. The use of internet technology for psychoeducation and support with dementia caregivers. Psychol Serv. 2012;9(2):215–8. A large randomized trial evaluated the benefits of online education, support, and self-care promotion for caregivers of persons with dementia. Anecdotal reports from participants indicated enjoyment of the materials, convenient access from home, and support from professionals and other caregivers. A substantial number of screened caregivers experienced obstacles of access, cost, and time regarding use of technology. Future caregiving generations are expected to have increased exposure and willingness to use computer technology.

Parker D, Mills S, Abbey J. Effectiveness of interventions that assist caregivers to support people with dementia living in the community: a systematic review. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2008;6(2):17–172.

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cox, C. Factors Associated with the Health and Well-being of Dementia Caregivers. Curr Tran Geriatr Gerontol Rep 2, 31–36 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-012-0033-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-012-0033-2