Abstract

Using population intercensus and national survey data, we examine marriage timing in urban China spanning the past six decades. Descriptive analysis from the intercensus shows that marriage patterns have changed in China. Marriage age is delayed for both men and women, and prevalence of nonmarriage became as high as one-quarter for men in recent birth cohorts with very low levels of education. Capitalizing on individual-level survey data, we further explore the effects of demographic and socioeconomic determinants of entry into marriage in urban China over time. Our study yields three significant findings. First, the influence of economic prospects on marriage entry has significantly increased during the economic reform era for men. Second, the positive effect of working in the state-owned sector has substantially weakened. Third, educational attainment now has a negative effect on marriage timing for women. Taken together, these results suggest that the traditional hypergamy norm has persisted in China as an additional factor in the influences of economic resources on marriage formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although the legal marriage age in China is among the highest in the world, at ages 22 for men and 20 for women since 1981, many studies have shown that marriage before the legal marriage age has been widely practiced, even during the most recent post-reform era (Guo 1999; Liu and Zhao 2009; Yu et al. 1994). In our data, 12.2 % of men and 13.7 % of women married before they reached the legal marriage age. To be inclusive of all marriages, we define the beginning of marriage risk at age 15 instead of the legal marriage age.

By the household registration (hukou) system, society in Mainland China has been partitioned into two distinct parts: rural and urban (Wu and Treiman 2007). Almost all aspects of life differ between rural and urban areas.

For the late-reform cohort, we restricted the sample to people who were over age 25 in 2005.

First, we pool the three cohorts and estimate the logit model with all the other variables in Tables 2 and 3 and their interactions with dummy variables representing cohorts. Then we reestimate a restricted version of the same model, deleting the interaction between the cohort dummy variables and one particular variable at a time. We obtain chi-square test statistics from such nested models for the null hypothesis that a particular variable has the same effect on marriage entry across the three cohorts. We report the statistical significance of the tests in the last columns of Tables 2 and 3.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for making this suggestion. The legal marriage ages were 18 for men and 20 for women, per the first Marriage Law of China in 1950. They were revised upward to 20 for men and 22 for women in the Amendment to The Marriage Law in 1980. Consequently, we tried different spline specifications by gender and cohorts. For the pre-reform cohort, the spline cut is set to <20, 20–26, 26–30, and >30 years old for men and to <18, 18–26, 26–30, and >30 years old for women. For the early-reform and late-reform cohorts, the spline cut is set to <22, 22–26, 26–30, and >30 years old for men and to <20, 20–26, 26–30, and >30 years old for women. We obtained similar results under the different specifications.

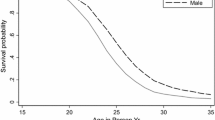

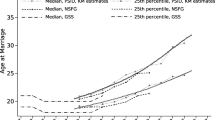

We first derived predicted marriage probabilities by duration and then calculated cumulative survival probabilities, using estimates reported in Tables 4 and 5. We fixed other covariates at the following values: being currently employed in the nonstate sector, not being enrolled in school, having an urban hukou, Han ethnicity, and father having only primary school education.

References

Allison, P. D. (1995). Survival analysis using the SAS system: A practical guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81(8), 13–46.

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of marriage: Part II. Journal of Political Economy, 82(2), S11–S26.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bian, Y. (2002). Chinese social stratification and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 91–116.

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Huinink, J. (1991). Human capital investments or norms of role transition? How women’s schooling and career affect the process of family formation. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 143–168.

Bulcroft, R. A., & Bulcroft, K. A. (1993). Race differences in attitudinal and motivational factors in the decision to marry. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 338–355.

Cai, Y., & Wang, F. (2014). From collective synchronization to individual liberalization: (Re)emergence of late marriage in Shanghai. In D. Davis & S. Freedman (Eds.), Sexuality and marriage in cosmopolitan China (pp. 97–117). Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Casterline, J. B. (1994). Fertility transition in Asia. In T. Locoh & V. H. Liège (Eds.), The onset of fertility transition in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 69–86). Liège, Belgium: Derouaux Ordina.

Chen, P.-C., & Kols, A. (1982). Population and birth planning in the People’s Republic of China (Population Reports, Series J, No. 25). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chen, Y.-H., & Chen, H. (2014). Continuity and changes in the timing and formation of first marriage among postwar birth cohorts in Taiwan. Journal of Family Issues, 35, 1584–1604.

Cherlin, A. J. (1980). Postponing marriage: The influence of young women’s work expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42, 355–365.

Coale, A., & Treadway, R. (1986). A summary of the changing distribution of overall fertility, marital fertility, and the proportion married in the provinces of Europe. In A. Coale & S. Watkins (Eds.), The decline of fertility in Europe (pp. 31–181). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Cooney, T. M., & Hogan, D. P. (1991). Marriage in an institutionalized life course: First marriage among American men in the twentieth century. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 178–190.

Coughlin, T., & Drewianka, S. (2011). Can rising inequality explain aggregate trends in marriage? Evidence from U.S. states, 1977–2005. B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 11, Article 3. Retrieved from https://pantherfile.uwm.edu/coughli2/www/Inequality%20and%20Marriage2.pdf

Cready, C. M., Fossett, M. A., & Kiecolt, K. J. (1997). Mate availability and African American family structure in the U.S. nonmetropolitan South, 1960–1990. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59, 192–203.

Davis, D. (2005). Urban consumer culture. China Quarterly, 183, 677–694.

Davis, D. S. (1992). Skidding: Downward mobility among children of the Maoist middle class. Modern China, 18, 410–437.

Davis, D. S. (2000). Reconfiguring Shanghai households. In B. Entwisle & G. Henderson (Eds.), Redrawing boundaries (pp. 245–260). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fincher, L. H. (2012, October 11). China’s “leftover” women. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/12/opinion/global/chinas-leftover-women.html?_r=0

Fukuda, S. (2013). The changing role of women’s earnings in marriage formation in Japan. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 646, 107–128.

Goldscheider, F. K., & Waite, L. J. (1986). Sex differences in the entry into marriage. American Journal of Sociology, 92, 91–109.

Goldstein, J. R., & Kenney, C. T. (2001). Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. women. American Sociological Review, 66, 506–519.

Gould, E. D., & Paserman, M. D. (2003). Waiting for Mr Right: Rising inequality and declining marriage rates. Journal of Urban Economics, 53, 257–281.

Guo, Z. (1999). Early marriage in Beijing [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 3, 1–10.

Kalmijn, M. (2013). The educational gradient in marriage: A comparison of 25 European countries. Demography, 50, 1499–1520.

Kuo, Y.-C. (2003). Wage inequality and propensity to marry after 1980 in Taiwan. Journal of Urban Economics, 53, 257–281.

Lee, J., & Wang, F. (1999). One quarter of humanity: Malthusian mythology and Chinese realities, 1700–2000. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Moors, G. (2000). Recent trends in fertility and household formation in the industrialized world. Review of Population and Social Policy, 9, 121–170.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review, 14, 1–45.

Lichter, D. T., LeClere, F. B., & McLaughlin, D. K. (1991). Local marriage markets and the marital behavior of black and white women. American Journal of Sociology, 96, 843–867.

Lichter, D. T., McLaughlin, D. K., & Ribar, D. C. (2002). Economic restructuring and the retreat from marriage. Social Science Research, 31, 230–256.

Liu, J., & Zhao, G. (2009). Study on the age at first marriage pattern of urban male and female in China: Based on CGSS2005 database [in Chinese]. Population and Development, 15(4), 13–21.

Lloyd, K. M., & South, S. J. (1996). Contextual influences on young men’s transition to first marriage. Social Forces, 74, 1097–1119.

Logan, J. A., Hoff, P. D., & Newton, M. A. (2008). Two-sided estimation of mate preferences for similarities in age, education, and religion. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103, 559–569.

MacDonald, M. M., & Rindfuss, R. R. (1981). Earnings, relative income, and family formation. Demography, 18, 123–136.

Magistad, M. K. (2013, February 21). China’s “leftover women”, unmarried at 27. BBC News Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-21320560

Malhotra, A. (1997). Gender and the timing of marriage: Rural-urban differences in Java. Journal of Marriage and Family, 59, 434–450.

Mare, R. D., & Winship, C. (1991). Socioeconomic change and the decline of marriage for blacks and whites. In C. Jencks & P. E. Peterson (Eds.), The urban underclass (pp. 175–202). Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

McLanahan, S., & Casper, L. (1995). Growing diversity and inequality in the American family. In R. Farley (Ed.), State of the Union: America in the 1990s, Vol. 2: Social trends (pp. 1–45). New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2013). Educational statistics yearbook of China. Beijing, China: People’s Education Press.

Mu, Z., & Xie, Y. (2014). Marital age homogamy in China: A reversal of trend in the reform era? Social Science Research, 44, 141–157.

Nobles, J., & Buttenheim, A. (2008). Marriage and socioeconomic change in contemporary Indonesia. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 904–918.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 563–591.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1994). Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review, 20, 293–342.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1997). Women’s employment and the gain to marriage: The specialization and trading model. Annual Review of Sociology, 23, 431–453.

Oppenheimer, V. K., Kalmijn, M., & Lim, N. (1997). Men’s career development and marriage timing during a period of rising inequality. Demography, 34, 311–330.

Oppenheimer, V. K., & Lew, V. (1995). Marriage formation in the eighties: How important was women’s economic independence? In K. O. Mason & A. Jensen (Eds.), Gender and family change in industrialized countries (pp. 105–138). Oxford, UK: Clarendon.

Parish, W. L. (1981). Egalitarianism in Chinese society. Problems of Communism, 29, 37–53.

Parish, W. L. (1984). Destratification in China. In J. Watson (Ed.), Class and social stratification in post-revolution China (pp. 84–120). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Park, H., & Lee, J. K. (2014). Growing educational differentials in the retreat from marriage among Korean men (PSC Working Paper Series, WPS 14-5). Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/psc_working_papers/57

Parsons, T. (1949). The social structure of the family. In R. Anshen (Ed.), The family: Its function and destiny (pp. 173–201). New York, NY: Harper.

Preston, S. H., & Richards, A. T. (1975). The influence of women’s work opportunities on marriage rates. Demography, 12, 209–222.

Qian, Z., & Preston, S. H. (1993). Changes in American marriage, 1972 to 1987: Availability and forces of attraction by age and education. American Sociological Review, 58, 482–495.

Raymo, J. M. (2003). Educational attainment and the transition to first marriage among Japanese women. Demography, 40, 83–103.

Raymo, J. M., & Iwasawa, M. (2005). Marriage market mismatches in Japan: An alternative view of the relationship between women’s education and marriage. American Sociological Review, 70, 801–822.

Raymo, J. M., Park, H., Xie, Y., & Yeung, W.-J. J. (2015). Marriage and family in East Asia: Continuity and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 471–492.

Rindfuss, R. R., Tamaki, E., Piotrowski, M., Choe, M., Tsuya, N., & Bumpass, L. (2013 August). Social change, social networks, and family and fertility change in Japan. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP), Busan, South Korea.

Rosero-Bixby, L. (1996). Nuptiality trends and fertility transition in Latin America. In J. M. Gjuzman, S. Singh, G. Rodriguez, & E. A. Pantelides (Eds.), The fertility transition in Latin America (pp. 135–150). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30, 843–861.

Sassler, S. L., & Schoen, R. (1999). The effect of attitudes and economic activity on marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 147–159.

Schwartz, C. R. (2010). Pathways to educational homogamy in marital and cohabiting unions. Demography, 47, 735–753.

Schwartz, C. R., & Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage: From 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42, 621–646.

Song, X., & Xie, Y. (2014). Market transition revisited: Changing regimes of housing inequality in China, 1988–2002. Sociological Science, 1, 277–291.

South, S. J. (2001). The variable effects of family background on the timing of first marriage: United States, 1969–1993. Social Science Research, 30, 606–626.

Sweeney, M. M. (2002). Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. American Sociological Review, 67, 132–147.

Tang, W., & Parish, W. L. (2000). Chinese urban life under reform: The changing social contract. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Teachman, J. D., Polonko, K. A., & Leigh, G. K. (1987). Marital timing: Race and sex comparisons. Social Forces, 66, 239–268.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W., & Teachman, J. D. (1995). The influence of school enrollment and accumulation on cohabitation and marriage in early adulthood. American Sociological Review, 60, 762–774.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W., & Xie, Y. (2007). Marriage and cohabitation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Thornton, A., & Lin, H.-S. (1994). Social change and the family in Taiwan. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Waite, L. J., & Spitze, G. D. (1981). Young women’s transition to marriage. Demography, 18, 681–694.

Walder, A. G. (1986). Communist neo-traditionalism: Work and authority in Chinese industry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wang, F., & Mason, A. (2008). The demographic factor in China’s transitions. In L. Brandt & T. G. Rawski (Eds.), China’s great economic transformations (pp. 136–166). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wang, F., & Tuma, N. (1993, August–September). Changes in Chinese marriage patterns during the twentieth century. Paper presented at the IUSSP International Population Conference, Montreal, Canada.

Wang, F., & Yang, Q. (1996). Age at marriage and the first birth interval: The emerging change in sexual behavior among young couples in China. Population and Development Review, 22, 299–320.

Wei, S.-J., & Zhang, X. (2011). The competitive saving motive: Evidence from rising sex ratios and savings rates in China. Journal of Political Economy, 119, 511–564.

White, L. K. (1981). A note on racial differences in the effects of female economic opportunity on marriage rates. Demography, 18, 349–354.

Whyte, M. K. (1990). Changes in mate choice in Chengdu. In D. Davis & E. Vogel (Eds.), China on the eve of Tiananmen (pp. 181–213). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Wu, J., Gyourko, J., & Deng, Y. (2012). Evaluating conditions in major Chinese housing markets. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 3, 531–543.

Wu, X. (2002). Work units and income inequality: The effect of market transition in urban China. Social Forces, 80, 1069–1099.

Wu, X., & Treiman, D. J. (2007). Inequality and equality under Chinese socialism: The hukou system and intergenerational occupational mobility. American Journal of Sociology, 113, 415–445.

Xie, Y. (2011). Evidence-based research on China: A historical imperative. Chinese Sociological Review, 44(1), 14–25.

Xie, Y. (2013). Gender and family in contemporary China (Research Report 13-808). Ann Arbor: Population Studies Center, University of Michigan.

Xie, Y., Lai, Q., & Wu, X. (2009). Danwei and social inequality in contemporary urban China. Sociology of Work, 19, 283–306.

Xie, Y., Raymo, J., Goyette, K., & Thornton, A. (2003). Economic potential and entry into marriage and cohabitation. Demography, 40, 351–367.

Xu, X., & Whyte, M. K. (1990). Love matches and arranged marriages: A Chinese replication. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 709–722.

Yabiku, S. T. (2004). Marriage timing in Nepal: Organizational effects and individual mechanisms. Social Forces, 83, 559–586.

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2011). The varying display of “gender display”: A comparative study of mainland China and Taiwan. Chinese Sociological Review, 44(2), 5–30.

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2013). Social change and trends in determinants of entry to first marriage [in Chinese]. Sociological Research, 44, 1–25.

Yu, X., Wang, Z., & Yang, X. (1994). Assessment and impact of early marriage and early birth during 1980s in China [in Chinese]. Population Research, 18(1), 26–30.

Zang, X. (1993). Household structure and marriage in urban China: 1900–1982. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 24(1), 35–44.

Zeng, Z., & Xie, Y. (2008). A preference-opportunity-choice framework with applications to intergroup friendship. American Journal of Sociology, 114, 615–648.

Acknowledgments

Jia Yu’s research was supported by a research grant from the National Social Science Fund of China (No. 15CRK022). Yu Xie’s research was partially supported by a research grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71461137001) and the University of Michigan’s Population Studies Center, which receives core support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant R24HD041028). We thank Zheng Mu, Xiwei Wu, Yongai Jin, and Ting Chen for suggestions and help on early drafts of this article, as well as the helpful feedback of anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, J., Xie, Y. Changes in the Determinants of Marriage Entry in Post-Reform Urban China. Demography 52, 1869–1892 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0432-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0432-z