Abstract

Using longitudinal data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics linked to three decades of census data on immigrant settlement patterns, this study examines how the migration behaviors of native-born whites and blacks are related to local immigrant concentrations, and how this relationship varies across traditional and nontraditional metropolitan gateways. Our results indicate that regardless of gateway type, the likelihood of neighborhood out-migration among natives increases as the local immigrant population grows—an association that is not explained by sociodemographic characteristics of householders or by features of the neighborhoods and metropolitan areas in which they reside. Most importantly, we find that this tendency to move away from immigrants is pronounced for natives living in metropolitan areas that are developing into a major gateway—that is, a community that has experienced rapid recent growth in foreign-born populations. We also demonstrate that among mobile natives, the neighborhoods that they move to have substantially smaller immigrant concentrations than the ones they left, a finding that is especially evident in new gateway areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although the PSID was designed to be nationally representative of the U.S. population in 1968, the sample has maintained close correspondence with characteristics of the U.S. population (see Duffy and Sastry 2012), and supplemental analyses indicate that the geographic distribution of our analytic sample closely matches the distribution observed in census data between 1980 and 2009.

Models restricted to households remaining in the same metropolitan area between interviews yield results that are substantively and statistically similar to those presented here.

We also tested for associations with recent changes in local immigrant populations. We found that in models including both percentage immigrant and change in percentage immigrant over the last five years, immigrant change had a comparatively small association with out-migration, and its inclusion does not alter the results in a meaningful way.

We considered several alternative ways of defining gateways, including approaches that relax or stiffen requirements to be considered an established, new, or developing gateway. The results from these specifications are substantively consistent with those shown here. Our employed typology has the added benefit of approximating the midpoints of the range of coefficients on key variables and produces a classification of metropolitan areas that is consistent with Singer’s (2005) typology.

Racial/ethnic entropy is defined, for each tract, as \( E={\displaystyle \sum_{r=1}^R}{p}_r \ln \left(\frac{1}{p_r}\right) \), where p r refers to the proportion of group r in the tract. High values of E refer to tracts where the distribution of racial groups is relatively uniform. Unfortunately, tract data on the race or birth country of immigrant populations are not available for our entire study period. We did, however, consider (in supplemental analyses) the percentage of the tract that is ethnic Mexican, and found weak associations with native out-migration, suggesting that our observed associations do not simply reflect out-migration from local Mexican populations.

Characteristics of householders’ tracts of residence are treated as a Level 1 characteristic because there is too little clustering of PSID respondents within census tracts to warrant an additional level.

The correlations between neighborhood percentage immigrant and gateway types are all moderate to weak (under |.50|), reflecting the fact that there is substantial heterogeneity in neighborhood immigrant concentrations within gateway types.

Although the marginal effect of tract percentage immigrant in new gateways is small and nonsignifcant, the logit models indicate that for both blacks and whites, the effect is not significantly different from that in established gateways.

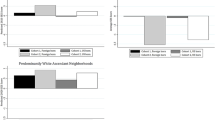

Racially pooled models with two- and three-way interactions indicate that the link between immigrant concentrations in origin and destination tracts varies significantly by race (p = .005), and differences in the association across different gateway types also vary significantly by race.

References

Blalock, H. (1967). Toward a theory of minority-group relations. New York, NY: Wiley.

Bobo, L. D. (1999). Prejudice as group position: Microfoundations of a sociological approach to racism and race relations. Journal of Social Issues, 55, 445–472.

Boustan, L. P. (2010). Was postwar suburbanization “white flight”? Evidence from the Black Migration. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125, 417–443.

Broder, T. (2007). State and local policies on immigrant access to services: Promoting integration of isolation? Los Angeles, CA: National Immigration Law Center.

Card, D., & DiNardo, J. (2000). Do immigrant inflows lead to native outflows? American Economic Review, 90, 360–367.

Carr, P. J., Lichter, D. T., & Kefelas, M. J. (2012). Can immigration save small-town America? Hispanic boomtowns and the uneasy path to renewal. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 641, 38–57.

Charles, C. Z. (2001). Processes of residential segregation. In A. O’Connor, C. Tilly, & L. Bobo (Eds.), Urban inequality: Evidence from four cities (pp. 217–271). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Charles, C. Z. (2006). Won’t you be my neighbor? Race, class, and residence in Los Angeles. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Clark, W. A. V. (1992). Residential preferences and residential choices in a multiethnic context. Demography, 29, 451–466.

Clark, W. A. V. (2009). Changing residential preferences across income, education, and age: Findings from the multi-city study of urban inequality. Urban Affairs Review, 44, 334–355.

Clark, W. A. V., & Blue, S. A. (2004). Race, class, and segregation patterns in U.S. immigrant gateway cities. Urban Affairs Review, 39, 667–688.

Crowder, K. (2000). The racial context of white mobility: An individual-level assessment of the white flight hypothesis. Social Science Research, 29, 223–257.

Crowder, K., Hall, M., & Tolnay, S. (2011). Neighborhood immigration and native out-mobility. American Sociological Review, 76, 25–47.

Crowder, K., Pais, J., & South, S. J. (2012). Neighborhood diversity, metropolitan constraints, and household migration. American Sociological Review, 77, 325–353.

De Jong, G., & Tran, Q.-G. (2001). Warm welcome, cool welcome: Mapping receptivity immigrants in the U.S. Population Today, 29, 1–4.

Dondero, M., & Muller, C. (2012). School stratification in new and established Latino destinations. Social Forces, 91, 477–502.

Duffy, D., & Sastry, N. (2012). An assessment of the national representativeness of children in the 2007 Panel Study of Income Dynamics (Technical Series Paper #12–01). Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Edin, P.-A., Fredriksson, P., & Åslund, O. (2003). Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants—Evidence from a natural experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 329–357.

Emerson, M. O., Yancey, G., & Chai, K. (2001). Does race matter in residential segregation: Exploring the preferences of white Americans. American Sociological Review, 66, 922–935.

Fasenfest, D., Booza, J., & Metzger, K. (2006). Living together: A new look at racial and ethnic integration in metropolitan neighborhoods, 1900–2000. In A. Berube, B. Katz, & R. Lang (Eds.), Redefining urban and suburban America: Evidence from Census 2000 (Vol. III, pp. 93–188). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Fennelly, K. (2008). Prejudice toward immigrants in the Midwest. In D. Massey (Ed.), New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration (pp. 151–178). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Fischer, M. (2010). Immigrant educational outcomes in new destinations: An exploration of high school attrition. Social Science Research, 39, 627–641.

Fischer, M., & Tienda, M. (2006). Redrawing spatial color lines: Hispanic metropolitan dispersal, segregation, and economic opportunity. In M. Tienda & F. Mitchell (Eds.), Hispanics and the future of America (pp. 100–138). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Frey, W. (1995). Immigration and internal migration flight from US metropolitan areas: Toward a new demographic Balkanization. Urban Studies, 32, 733–757.

Frey, W. (1996). Immigration, domestic migration, and demographic Balkanization in America: New evidence for the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 22, 741–763.

Frey, W., & Liaw, K.-L. (1998). Immigrant concentration and domestic migration dispersal: Is movement to non-metropolitan areas “white flight”? Professional Geographer, 50, 215–231.

Frey, W., & Liaw, K.-L. (2005). Migration within the United States: Role of race-ethnicity. Brookings-Wharton Papers of Urban Affairs, 2005, 207–262.

Gozdziak, E., & Martin, S. F. (2005). Beyond the gateway: Immigrants in a changing America. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Graefe, D. R., De Jong, G., Hall, M., Sturgeon, S., & VanEerden, J. (2008). Immigrants’ TANF eligibility, 1996–2003: What explains the new across-state inequalities. International Migration Review, 42, 89–133.

Greene, W. H. (2011). Econometric analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Grieco, E., Acosta, Y., da la Cruz, G. P., Gambino, C., Gryn, T., Larsen, L., . . . Walters, N. (2012). The foreign-born population the United States: 2010 (ACS Reports). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Hall, M. (2013). Residential integration on the new frontier: Immigrant segregation in established and new destinations. Demography, 50, 1873–1896.

Haubert, J., & Fussell, E. (2006). Explaining pro-immigrant sentiment in the U.S.: Social class, cosmopolitanism, and perceptions of immigrants. International Migration Review, 40, 489–507.

Hopkins, D. J. (2010). Politicized places: Explaining where and when immigrants provoke local opposition. American Political Science Review, 104, 40–60.

Iceland, J., & Nelson, K. (2008). Hispanic segregation in metropolitan America: Exploring the multiple forms of spatial assimilation. American Sociological Review, 73, 741–765.

Iceland, J., & Scopilliti, M. (2008). Immigrant residential segregation in U.S. metropolitan areas, 1990–2000. Demography, 45, 79–94.

Johnson, J. H., Farrell, W. C., Jr., & Guinn, C. (1999). Immigration reform and the browning of America: Tensions, conflicts, and community instability in metropolitan Los Angeles. In C. Hirschman, P. Kasinitz, & J. DeWind (Eds.), The handbook of international migration (pp. 390–411). New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Kirk, D. S., Papachristos, A. V., Fagan, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2012). The paradox of law enforcement in immigrant communities: Does tough immigration enforcement undermine public safety? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 641, 79–98.

Kritz, M., & Gurak, D. (2001). The impact of immigration on the internal migration of natives and immigrants. Demography, 38, 133–145.

Krysan, M. (2002). Community undesirability in black and white: Examining racial residential preferences through community perceptions. Social Problems, 49, 521–543.

Krysan, M., & Bader, M. (2007). Perceiving the metropolis: Seeing the city through a prism of race. Social Forces, 86, 699–727.

Krysan, M., & Farley, R. (2002). The residential preferences of blacks: Do they explain persistent segregation? Social Forces, 80, 937–980.

Ley, D. (2007). Countervailing immigration and domestic migration in gateway cities: Australian and Canadian variations on an American theme. Economic Geography, 83, 231–254.

Ley, D., & Tutchener, J. (2001). Immigration, globalisation and house price movements in Canada’s gateway cities. Housing Studies, 16, 199–223.

Lichter, D., & Johnson, K. (2009). Immigrant gateways and Hispanic migration to new destinations. International Migration Review, 43, 496–518.

Lichter, D., Parisi, D., Taquino, M., & Grice, S. M. (2010). Residential segregation in new Hispanic destinations: Cities, suburbs, and rural communities compared. Social Science Research, 39, 215–230.

Logan, J. R., & Alba, R. D. (1993). Locational returns to human capital: Minority access to suburban community resources. Demography, 30, 243–268.

Logan, J., & Stults, B. (2011). The persistence of segregation in the metropolis: New findings from the 2010 census (US2010 Project Report Series). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Logan, J. R., Xu, Z., & Stults, B. J. (2014). Interpolating U.S. decennial census tract data from as early as 1970 to 2010: A longitudinal tract database. Professional Geographer, 66, 412–420.

Marrow, H. (2011). New destinations dreaming: Immigration, race, and legal status in the rural American South. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University.

Massey, D. S. (1985). Ethnic residential segregation: A theoretical synthesis and empirical review. Sociology and Social Research, 69, 315–350.

Massey, D. S. (2008). Assimilation in a new geography. In D. S. Massey (Ed.), New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration (pp. 343–353). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

McClain, P., Lackey, G., Pérez, E., Cartera, N., Johnson Carew, J., Walton, E., Jr., & Nunnallya, S. (2011). Intergroup relations in three southern cities. In E. Telles, M. Sayer, & G. Rivera-Salgado (Eds.), Just neighbors? Research on African American and Latino relations in the United States (pp. 201–241). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

McConnell, E. D. (2008). The U.S. destinations of contemporary Mexican immigrants. International Migration Review, 42, 767–802.

McDermott, M. (2011). Black attitudes and Hispanic immigrants in South Carolina. In E. Telles, M. Sayer, & G. Rivera-Salgado (Eds.), Just neighbors? Research on African American and Latino relations in the United States (pp. 242–263). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Mood, C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26, 67–82.

O’Neil, K. S. (2012, May). Challenging change: Local policies and the new geography of American immigration. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, San Francisco, CA.

Pais, J., South, S., & Crowder, K. (2012). Metropolitan heterogeneity and minority neighborhood attainment. Social Problems, 59, 258–281.

Park, J., & Iceland, J. (2011). Residential segregation in metropolitan established immigrant gateways and new destinations, 1990–2000. Social Science Research, 40, 811–821.

Quillian, L. (2002). Why is black–white segregation so persistent? Evidence on three theories from migration data. Social Science Research, 31, 197–229.

Rosenbaum, E., & Friedman, S. (2007). The housing divide: How generations of immigrants fare in New York’s housing market. New York, NY: New York University.

Singer, A. (2005). The rise of new immigrant gateways: Historical flows, recent settlement trends. In B. Katz & R. E. Lang (Eds.), Redefining urban and suburban America: Evidence from Census 2000 (Vol. 1, pp. 41–86). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Steil, J. P., & Vasi, I. B. (2014). The new immigration contestation: Social movements and local immigration policy making in the United States, 2000–2011. American Journal of Sociology, 119, 1104–1155.

Timberlake, J., & Iceland, J. (2007). Change in racial and ethnic residential inequality in American cities, 1970–2000. City and Community, 6, 335–336.

Vaca, N. (2004). The presumed alliance: The unspoken conflict between Latinos and blacks and what it means for America. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

White, M. J. (1987). American neighborhoods and residential differentiation. New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Wilson, W. J., & Taub, R. P. (2006). There goes the neighborhood: Racial, ethnic, and class tensions in four Chicago neighborhoods and their meaning for America. New York, NY: Knopf.

Winders, J. (2008). Nashville’s new “Sonido”: Latino migration and the changing politics of race. In D. S. Massey (Ed.), New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Wright, R., Ellis, M., & Reibel, M. (1997). The linkage between immigration and internal migration in large metropolitan areas in the United States. Economic Geography, 73, 234–254.

Zelinsky, W., & Lee, B. A. (1998). Heterolocalism: An alternative model of the sociopolitical behaviour of immigrant ethnic communities. International Journal of Population Geography, 4, 281–298.

Zúñiga, V., & Hernández-León, R. (2005). New destinations: Mexican immigration in the United States. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sam Friedman, Jacob Hibel, John Iceland, Bob Kaestner, Maria Krysan, Barry Lee, Dan Lichter, Giovanni Peri, Emily Rosenbaum, Jeff Timberlake, and Stew Tolnay for comments on earlier versions of this article and to Brian Stults for generous support with the Longitudinal Tract Data Base. This research was supported by infrastructure grants to the Cornell University Cornell Population Center (R24 HD058488) and to the University of Washington Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology (R24 HD042828) by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Resource 1

(PDF 187 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hall, M., Crowder, K. Native Out-Migration and Neighborhood Immigration in New Destinations. Demography 51, 2179–2202 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0350-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0350-5