Abstract

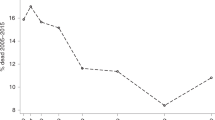

Debilitating events could leave either more frail or more robust survivors, depending on the extent of scarring and mortality selection. The majority of empirical analyses find more frail survivors. I find heterogeneous effects. Among severely stressed former Union Army prisoners of war (POWs), the effect that dominates 35 years after the end of the Civil War depends on age at imprisonment. Among survivors to 1900, those younger than 30 at imprisonment faced higher old-age mortality and morbidity and worse socioeconomic outcomes than non-POW and other POW controls, whereas those older than 30 at imprisonment faced a lower older-age death risk than the controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See U.S. War Department (1880–1901, Series II, Vol. VIII:615, 781). In a longitudinal random sample, roughly 38 % of the 554 men held at Andersonville died there. In the National Park Service’s cross-sectional database, 40 % of the listed men died at Andersonville (see Costa and Kahn 2007).

Estimated from a random sample of Union Army soldiers.

Estimated from the figures in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2004) and from http://www.phil.muni.cz/~vndrzl/amstudies/civilwar_stats.htm.

Testimony from the trial of Captain Wirtz, reprinted in Ransom (1963).

The data are available at http://www.cpe.uchicago.edu and were collected by a team of researchers led by Robert Fogel. The sample of 35,570 represents roughly 1.3 % of all whites mustered into the Union Army and 8 % of all regiments that composed the Union Army. Ninety-one percent of the sample consists of volunteers, with the remainder evenly divided between draftees and substitutes. The data are based on a 100 % sample of all enlisted men in 331 randomly chosen companies. The sample is limited to 303 companies because complete data are not yet available on all 331companies.

Linkage to the 1860 census reveals that the sample is representative of the northern population of military age in terms of 1860 real estate and personal property wealth and in terms of literacy rates.

Because of the system of prisoner exchange (and the hope that it would be revived), the South had an incentive to record information on men who were captured.

A searchable version of the database is available online as part of the Soldiers and Sailors system (http://www.itd.nps.gov/cwss).

Because information on cause of death comes from the pension records, men—from the researcher’s point of view—are not at risk to die until they are on the pension rolls. By 1900, an estimated 85 % of all Union Army veterans were on the pension rolls. Those not eligible for pensions included deserters (roughly 14 % of war survivors had ever deserted) and men who had served less than 90 days. Men who entered the rolls after 1900 were probably healthier. The percentage of veterans alive in 1900 who entered the rolls later was 8 % for non-POWs, 8 % for Fogel sample POWs, and 5 % for the Andersonville sample. My comparisons of POWs with non-POWs in 1900 may therefore understate health and subsequent mortality differences.

Shell shock, combat fatigue, and post-traumatic stress (all names for the same phenomenon in different wars) were not recognized as disorders either during or after the Civil War (see Hyams et al. 1996 for a history of PTSD). The records therefore provide little information on psychiatric disorders.

WWII POWs held by the Japanese experienced higher mortality rates for at least eight years after the war, whereas those held by the Germans did not. Excess mortality was due to tuberculosis and to trauma, including suicide, with the highest mortality rates among the youngest men (Cohn and Cooper 1954; Keehn 1980; Nefzger 1970).

Additional socioeconomic variables were investigated, including whether the veteran was a private (privates faced higher mortality rates in POW camps than nonprivates), but none of these were statistically significant, and none affected the other coefficients.

Even with no controls for type of POW, a mention of scurvy was not a statistically significant predictor of death.

References

Almond, D., & Mazumder, B. (2005). The 1918 influenza pandemic and subsequent health outcomes: An analysis of SIPP data. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 95, 258–262.

Barker, D. J. P. (1992). Fetal and infant origins of adult disease. London, UK: British Medical Publishing Group.

Barker, D. J. P. (1994). Mothers, babies, and disease in later life. London, UK: British Medical Publishing Group.

Basile, L. (Ed). (1981). The Civil War diary of Amos E. Stearns, a prisoner at Andersonville. Rutherford, NJ: Farleigh Dickinson University Press and London, UK: Associated Press.

Caselli, G., & Capocaccia, R. (1989). Age, period, cohort and early mortality: An analysis of adult mortality in Italy. Population Studies, 43, 133–153.

Casiero, D., & Frishman, W. H. (2006). Cardiovascular complications of eating disorders. Cardiology in Review, 14, 227–231.

Cohn, B. M., & Cooper, M. (1954). A follow-up study of World War II prisoners of war (VA medical monograph). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Collins, C., Burazeri, G., Gofin, J., & Kark, J. D. (2004). Health status and mortality in holocaust survivors living in Jerusalem 40–50 years later. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17, 403–411.

Costa, D. L. (2000). Understanding the twentieth century decline in chronic conditions among older men. Demography, 37, 53–72.

Costa, D. L. (2002). Changing chronic disease rates and long-term declines in functional limitation among older men. Demography, 39, 119–138.

Costa, D. L., & Kahn, M. E. (2007a). Deserters, social norms, and migration. Journal of Law and Economics, 50, 323–353.

Costa, D. L., & Kahn, M. E. (2007b). Surviving Andersonville: The benefits of social networks in POW camps. American Economic Review, 97, 1467–1487.

Costa, D. L., & Kahn, M. E. (2008). Heroes and cowards: The social face of war. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dent, O. F., Richardson, B., Wilson, S., Goulston, K. J., & Murdoch, C. W. (1989). Postwar mortality among Australian World War II prisoners of the Japanese. Medical Journal of Australia, 150, 378–382.

Edozien, J. C., & Rahim-Khan, M. A. (1968). Anaemia in protein malnutrition. Clinical Science, 34, 315–326.

Fairfield, K. M., & Fletcher, R. H. (2002). Vitamins for chronic disease prevention in adults. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287, 3116–3126.

Finch, C. E., & Crimmins, E. M. (2004). Inflammatory exposure and historical changes in human life-spans. Science, 305, 1736–1739.

Finlayson, R. (1985). Ischaemic heart disease, aortic aneurysms, and atherosclerosis in the city of London, 1868–1982. In W. F. Brynum, C. Lawrence, & V. Nutton (Eds.), The emergence of modern cardiology (pp. 151–168). London, UK: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine.

Fleming, P. R. (1997). A short history of cardiology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands–Atlanta, GA: Rodopi.

Gill, G. (1983). Study of mortality and autopsy findings amongst former prisoners of war of the Japanese. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 129, 11–13.

Goss, W. L. (1866). The soldier’s story of his captivity at Andersonville, Belle isle, and other rebel prisons. Boston, MA: Lee & Shepard. Reproduced 2001 by Digital Scanning, Scituate, MA.

Goulston, K. J., Dent, O. F., Chapuis, P. H., Chapman, G., Smith, C. I., Tait, A. D., & Tennant, C. C. (1985). Gastrointestinal morbidity among World War II prisoners of war: 40 years on. The Medical Journal of Australia, 143, 6–10.

Horiuchi, S. (1983). The long-term impact of war on mortality: Old-age mortality of the first World War survivors in the Federal Republic of Germany. Population Bulletin of the United Nations, 15, 80–92.

Horiuchi, S., & Wilmoth, J. R. (1998). Deceleration in the age pattern of mortality at older ages. Demography, 35, 391–412.

Hyams, K. C., Wignall, F. S., & Roswell, R. (1996). War syndromes and their evaluation: From the U.S. Civil War to the Persian Gulf War. Annals of Internal Medicine, 125, 398–405.

Kang, H. K., Bullman, T. A., & Taylor, J. W. (2006). Risk of selected cardiovascular diseases and posttraumatic stress disorder among former World War II prisoners of war. Annals of Epidemiology, 16, 381–386.

Kannisto, V., Christensen, K., & Vaupel, J. W. (1997). No increased mortality in later life for cohorts born during famine. American Journal of Epidemiology, 145, 987–994.

Keehn, R. J. (1980). Follow-up studies of World War II and Korean conflict prisoners, III: Mortality to January 1, 1976. American Journal of Epidemiology, 111, 194–211.

Keys, A., Brožek, J., Henschel, A., Mickelsen, O., & Taylor, H. L. (1950). The biology of human starvation. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Lee, C. (2005). Wealth accumulation and the health of union army veterans, 1860–1870. Journal of Economic History, 65, 352–385.

Linderman, G. F. (1987). Embattled courage: The experience of combat in the American Civil War. New York: Free Press.

Manton, K. G., & Stallard, E. (1981). Methods for evaluating the heterogeneity of aging processes in human populations using vital statistics data: Explaining the black/white mortality crossover by a model of mortality selection. Human Biology, 53, 47–67.

Marvel, W. (1994). Andersonville: The last depot. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Moody, H. R. (2010). Aging: Concepts and controversies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine-Forge Press.

Niles, G. M. (1912). Pellagra, an America problem. Philadelphia, PA, and London, UK: W.B. Saunders Company.

Page, W. F. (1992). The health of former prisoners of war: Results from the medical examination survey of former POWs of World War II and the Korean conflict. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Page, W. F., & Brass, L. M. (2001). Long-term heart disease and stroke mortality among former American prisoners of war of World War II and the Korean conflict: Results of a 50-year follow-up. Military Medicine, 166, 803–808.

Page, W. F., Engdahl, B. E., & Eberly, R. E. (1991). Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among former prisoners of war. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 179, 670–677.

Page, W. F., & Ostfeld, A. M. (1994). Malnutrition and subsequent ischemic heart disease in former prisoners of war of World War II and Korean conflict. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 47, 1437–1441.

Preston, S. H., Elo, I. T., Rosenwaike, I., & Hill, M. (1996). African-American mortality at older ages: Results of a matching study. Demography, 33, 193–209.

Ransom, J. (1963). John Ransom’s Andersonville diary. New York: Berkley Books.

Rhodes, J. F. (1904). History of the United States of America: From the compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan campaign of 1896, Vol. 5, 1864–1866. New York: Macmillan.

Schnitker, M. A., Mattman, P. E., & Bliss, T. L. (1951). A clinical study of malnutrition in Japanese prisoners of war. Annals of Internal Medicine, 35, 69–96.

Speer, L. R. (1997). Portals to hell: Military prisons of the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

Tennant, C., Goulston, K., & Dent, O. (1986). The psychological effects of being a prisoner of war: Forty years after release. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 143, 618–621.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Policy. (2004). Former American prisoners of war (POWs). http://www.vba.va.gov/bln/21/Benefits/POW/DOCS/POW6-29-04.doc

U.S. War Department. (1880–1901). The war of the rebellion: A compilation of the official records of the union and confederate armies. Washington, DC: U.S Government Printing Office. http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/moa/browse.monographs/waro.html

Waaler, H. T. (1984). Height, weight, and mortality: The Norwegian experience. Acta Medica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 679, 1–56.

Webb, J. G., Kiess, M. C., & Chan-Yan, C. C. (1986). Malnutrition and the heart. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 135, 753–758.

Williams, R. L., Medalie, J. H., Zyzanksi, S. J., Flocke, S. A., Yaari, S., & Goldbourt, U. (1993). Long term mortality of Nazi concentration camp survivors. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 46, 573–575.

Acknowledgments

I thank Matthew Kahn, Louis Nguyen, Irwin Rosenberg, Nevin Scrimshaw, Avron Spiro, the participants of the UCLA Economic History Proseminar, and four anonymous referees for comments. I gratefully acknowledge the support of NIH grants R01 AG19637 and P01 AG10120 and data provided by a subgrant from P30 AG017265.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Costa, D.L. Scarring and Mortality Selection Among Civil War POWs: A Long-Term Mortality, Morbidity, and Socioeconomic Follow-Up. Demography 49, 1185–1206 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0125-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0125-9