Abstract

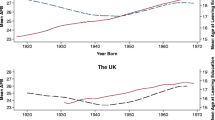

Researchers have long been interested in the influence of family size on children’s educational outcomes. Simply put, theories have suggested that resources are diluted within families that have more children. Although the empirical literature on developed countries has generally confirmed the theoretical prediction that family size is negatively related to children’s education, studies focusing on developing societies have reported heterogeneity in this association. Recent studies addressing the endogeneity between family size and children’s education have also cast doubt on the homogeneity of the negative role of family size on children’s education. The goal of this study is to examine the causal effect of family size on children’s education in Brazil over a 30-year period marked by important social and demographic change, and across extremely different regions within the country. We implement a twin birth instrumental variable approach to the nationally representative 1977–2009 PNAD data. Our results suggest an effect of family size on education that is not uniform throughout a period of significant social, economic, and demographic change. Rather, the causal effect of family size on adolescents’ schooling resembles a gradient that ranges from positive to no effect, trending to negative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the terms family size, sibship size, and number of siblings synonymously.

Economic theory also posits a negative association while contending that parents invest in their children based on assessments of children’s differential ability to contribute to the wealth of the entire family, therefore generating inequities within siblings (Becker 1981). Confluence theory predicts a negative effect of family size on children’s education, suggesting that the mechanism lowering per-child education in larger families is the family’s average intellectual environment (Zajonc and Markus 1975).

Guo and VanWey (1999) were the first to use sibling fixed-effect models to handle the endogeneity resulting from parents with lower cognitive abilities having larger families. They found that the effects of family size on education disappear. Although this approach focuses on the bias from parents’ preferences given their education, it does not handle the endogeneity resulting from parents adjusting their fertility in response to desired children’s education.

While researchers cannot assert that couples have complete control over their childbearing, the use of contraception and reports on desired family sizes provide an idea of the extent to which limiting family size is in couples’ agenda.

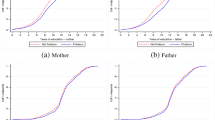

Because of the inexistence of panel data on education in Brazil to follow the same sample as it ages, we follow a nationally representative cohort at ages 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 using the PNAD data (available from authors upon request). The repeated cross sections allow for examining the educational distribution of a cohort as it ages. We find that while the distribution of education as a cohort ages yields higher means of completed schooling, it also produces larger standard deviations.

Fertility treatments became accessible in Brazil in the late 1990s (Borlot and Trindade 2004). Being precise about the number of fertility clinics and procedures is impossible because no specific legislation regulates the practice. The Latin American Registry System (Registro Latinoamericano de Reproducción Asistida)—a surveillance system covering more than 90 % of the centers offering such technologies in Latin America—estimates that the entire region has nearly 90 clinics (Zegers-Hochschild 2002). A report from the World Health Organization estimates that 6,480 live births were produced via reproductive techniques in the region from 1991 to 1998 (Zegers-Hochschild 2002). It is estimated that Brazil shares 42.9 % of the cases, which yields 308 cases per year during this eight-year period. Based on the Demographic and Health Surveys report of 3,495,249 live births in Brazil in 1996 (Macro International 1996), we roughly estimate that 0.000088 of these births could have been produced through a fertility technology treatment, a small enough proportion not to significantly affect our analysis.

References

Angrist, J., Lavy, V., & Schlosser, A. (2010). Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Labor Economics, 28, 773–824.

Anh, T., Knodel, J., Lam, D., & Friedman, J. (1998). Family size and children’s education in Vietnam. Demography, 35, 57–70.

Ariza, M., & Oliveira, O. (2005). Families in transition. In C. Wood & B. Roberts (Eds.), Rethinking development in Latin America (pp. 262–284). University Park, PA: Penn State University Press.

Axinn, W. (1993). The effects of children’s schooling on fertility limitation. Population Studies, 47, 481–493.

Barros, R., & Lam, D. (1996). Income and educational inequality and children’s schooling attainment. In N. Birdsall & R. Sabot (Eds.), Opportunity foregone: Education in Brazil (pp. 337–363). Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Becker, G. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Behrman, J., Rosenzweig, M., & Taubman, P. (1994). Endowments and the allocation of schooling in the family and in the marriage market: The twins experiment. Journal of Political Economy, 102, 1131–1174.

Birdsall, N., & Sabot, R. (Eds.). (1996). Opportunity foregone: Education in Brazil. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Black, S., Devereux, P., & Salvanes, K. (2005). The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 669–700.

Black, S., Devereux, P., & Salvanes, K. (2010). Small family, smart family? Family size and the IQ score of young men. The Journal of Human Resources, 45, 33–58.

Blake, J. (1981). Family size and achievement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Borlot, A. M., & Trindade, Z. A. (2004). As tecnologias de reprodução assistida e as representações sociais do filho biológico [The reproductive technologies and the social representations of biological children]. Estudos de Psicologia, 9, 63–70.

Buchman, C. (2000). Family structure, parental perceptions, and child labor in Kenya: What factors determine who is enrolled in school? Social Forces, 78, 1349–1379.

Buchman, C., & Hannum, E. (2001). Education and stratification in developing countries: A review of theories and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 77–102.

Cáceres-Delpiano, J. (2006). The impacts of family size on investment in child quality. Journal of Human Resources, 41, 738–754.

Caldwell, J. (1982). Theory of fertility decline. London, UK: Academic Press.

Caldwell, J., Reddy, P., & Caldwell, P. (1985). Educational transition in rural south India. Population and Development Review, 11, 28–51.

Conley, D., & Glauber, R. (2006). Parental educational investment and children’s academic risk: Estimates of the impact of sibship size and birth order from exogenous variation in fertility. The Journal of Human Resources, 41, 722–737.

Diniz, C. (2002). A nova configuração urbano-industrial no Brasil [The new urban-industrial configuration of Brazil] In A. Kon (Ed.), Unidade e fragmentação: A questão regional no Brasil. São Paulo, Brazil: Perspectiva.

Entwisle, D., Alexander, K., & Olson, L. (2005). First grade and educational attainment by age 22: A new story. The American Journal of Sociology, 110, 1458–1502.

Gomes-Neto, J. B., & Hanushek, E. (1994). The causes and consequences of grade repetition: Evidence from Brazil. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 43, 117–148.

Guo, G., & VanWey, L. (1999). Sibship size and intellectual development: Is the relationship causal? American Sociological Review, 64, 169–187.

Hauser, R., & Sewell, W. (1985). Birth order and educational attainment in full sibships. American Educational Research Journal, 22, 1–23.

Kelley, A. (1996). The consequences of rapid population growth on human resource development: The case of education. In D. A. Ahlburg, A. C. Kelley, & K. O. Mason (Eds.), The impact of population growth on well-being in developing countries (pp. 67–137). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

Knodel, J., Havanon, N., & Sittitrai, W. (1990). Family size and the education of children in the context of rapid fertility decline. Population and Development Review, 16, 31–62.

Knodel, J., & Wongsith, M. (1991). Family size and children’s education in Thailand: Evidence from a national sample. Demography, 28, 119–131.

Lam, D., & Duryea, S. (1999). The effects of education on fertility, labor supply, and investments in children, with evidence from Brazil. Journal of Human Resources, 34, 160–192.

Lam, D., & Levison, D. (1992). Age, experience, and schooling: Decomposing earnings inequality in the United States and Brazil. Sociological Inquiry, 62, 220–245.

Lam, D., & Marteleto, L. (2008). Stages of the Demographic transition from a child’s perspective: Family size, cohort size, and children’s resources. Population and Development Review, 34, 225–252.

Li, H., Zhang, J., & Zhu, Y. (2008). The quantity-quality trade-off of children in a developing country: Identification using Chinese twins. Demography, 45, 223–243.

Lloyd, C. B. (1994). Investing in the next generation: The implications of high fertility at the level of the family. In R. Cassen (Ed.), Population and development: Old debates, new conclusions (pp. 181–202). Washington, DC: Overseas Development Council.

Lloyd, C. B., & Blanc, A. K. (1996). Children’s schooling in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of fathers, mothers, and others. Population and Development Review, 22, 265–298.

Lloyd, C. B., & Gage-Brandon, A. J. (1994). High fertility and children’s schooling in Ghana: Sex differences in parental contributions and educational outcomes. Population Studies, 48, 293–306.

Lu, Y. (2009). Sibship Size, Family Organization, and Education in South Africa: Black-White Variations. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 27, 110–125.

Lu, Y., & Treiman, D. (2008). The effect of sibship size on educational attainment in China: Period variations. American Sociological Review, 73, 813–834.

Macro International and Brazilian Society for Family Welfare (BEMFAM). (1996). Brazil Demographic and Health Survey 1996. Calverton, MD: Macro International, Inc.

Maralani, V. (2008). The changing relationship between family size and educational attainment over the course of socioeconomic development: Evidence from Indonesia. Demography, 45, 693–717.

Martine, G. (1996). Brazil’s fertility decline, 1965–95: A fresh look at key factors. Population and Development Review, 22, 47–75.

Ministério da Saúde. (2008). Pesquisa Nacional de Demografia e Saúde da Mulher e da Criança (PNDS) 2006: Relatório Final [Final Report of the National Demographic and Health Survey 2006]. Brasília, Brazil: Ministério da Saúde.

Minnesota Population Center. (2010). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 6.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Moffitt, R. (2005). Remarks on the analysis of causal relationships in population research. Demography, 42, 91–108.

Mueller, E. (1984). Income, aspirations, and fertility in rural areas of less developed countries. In W. A. Schutjer & C. Shannon Stokes (Eds.), Rural development and human fertility (pp. 121–150). New York: Macmillan.

Parish, W. L., & Willis, R. (1993). Daughters, education, and family budgets: Taiwan experiences. The Journal of Human Resources, 28, 863–898.

Patrinos, H. A., & Psacharopoulos, G. (1997). Family size, schooling and child labor in Peru—An empirical analysis. Journal of Population Economics, 10, 387–405.

Pong, S. (1997). Sibship size and educational attainment in Peninsular Malaysia: Do policies matter? Sociological Perspectives, 40, 227–242.

Post, D. (2002). Children’s work, schooling, and welfare in Latin America. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Post, D., & Pong, S. (1998). Intra-family educational inequality in Hong Kong: The waning effect of sibship composition. Comparative Education Review, 42, 99–117.

Potter, J. (1999). The persistence of outmoded contraceptive regimes: The cases of Mexico and Brazil. Population And Development Review, 25, 703–739.

Potter, J., Schmertmann, C., Assunção, R., & Cavenaghi, S. (2010). Mapping the timing, pace, and scale of the fertility transition in Brazil. Population and Development Review, 36, 283–307.

Potter, J., Schmertmann, C., & Cavenaghi, S. (2002). Fertility and development: Evidence from Brazil. Demography, 39, 739–761.

Powell, B., & Steelman, L. (1993). The educational benefits of being spaced out: Sibship density and educational progress. American Sociological Review, 58, 367–381.

Powell, B., Werum, R., & Steelman, L. (2004). Linking public policy, family structure, and educational outcomes. In D. Conley & K. Albright (Eds.), After the bell: Family background, public policy and educational success (pp. 111–144). New York: Routledge.

Psacharopoulos, G., & Arriagada, A. (1989). The determinants of early age human capital formation: Evidence from Brazil. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 37, 683–708.

Rosenzweig, M., & Wolpin, K. (1980). Testing the quantity-quality fertility model: The use of twins as a natural experiment. Econometrica, 48, 227–240.

Rosenzweig, M., & Wolpin, K. (2000). Natural “natural experiments” in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 38, 827–874.

Saad, P. (2004). Transferência de Apoio Intergeracional no Brasil e na América Latina [Intergenerational Transfers in Brazil and Latin America]. In A. Camarano (Ed.), Os Novos Idosos Brasileiros: Muito Além dos 60? (pp. 169–210). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: IPEA.

Shavit, Y., & Pierce, J. (1991). Sibship size and educational attainment in nuclear and extended families: Arabs and Jews in Israel. American Sociological Review, 56, 321–330.

Steelman, L., & Powell, B. (1991). Sponsoring the next generation: Parental willingness to pay for higher education. The American Journal of Sociology, 96, 1505–1529.

Steelman, L., Powell, B., Werum, R., & Cater, S. (2002). Reconsidering the effects of sibling configuration. Annual Review of Sociology, 23, 243–270.

United Nations Population Division. (2010). World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision. New York: United Nations.

Veloso, F. (2009). 15 anos de avanços na educação no Brasil: Onde estamos? [15 years of advances in Brazilian education: Where are we?]. In F. Veloso, S. Pessôa, R. Henriques, & F. Giambiagi (Eds.), Educação básica no Brasil: Construindo o país do futur (pp. 3–24). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Elsevier.

Wajnman, S., & Rios-Neto, E. (1999). Women’s participation in the labor market in Brazil: Elements for projecting levels and trends. Brazilian Journal of Population Studies, 2, 41–54.

Yu, W.-H., & Su, K.-H. (2006). Gender, sibship structure, and educational inequality in Taiwan: Son preference revisited. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 1057–1068.

Zajonc, R., & Markus, G. (1975). Birth order and intellectual development. Psychological Review, 82, 74–88.

Zegers-Hochschild, F. (2002). The Latin American Registry of Assisted Reproduction. In E. Vayena, P. Rowe, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Current practices and controversies in assisted reproduction: Report of a WHO meeting (pp. 355–364). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 5 R24 HD042849 awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health and Child Development. Souza gratefully acknowledges financial support from the International Training Program in Population Health funded by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to Eduardo Rios-Neto, Robert Hummer, Kelly Raley, the participants of the Education and Transitions to Adulthood Group at the University of Texas at Austin, three anonymous reviewers, and one deputy editor and the Editor of Demography for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 184 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marteleto, L.J., de Souza, L.R. The Changing Impact of Family Size on Adolescents’ Schooling: Assessing the Exogenous Variation in Fertility Using Twins in Brazil. Demography 49, 1453–1477 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0118-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0118-8