Abstract

Discharge of azo dyes by textile and allied industries to the environment is a growing problem. Degradation of an azo dye, methyl orange (MO), was tested in simulated wastewater with different oxide nanomaterials acting as photocatalysts under visible light. Titanium dioxide (TiO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), and graphene oxide (GO) were synthesized, characterized, and applied for adsorptive and photocatalytic removal of the dye. Factors such as initial concentration of MO and size of nanoparticle photocatalyst were varied to determine the optimum conditions for dye removal. Finally, nanocomposites of the three materials (GO–TiO2–ZnO) were synthesized and tested for its photocatalytic performance. The composition of the individual oxide in the nanocomposite was then varied to achieve the best photocatalytic performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Textile and dye-manufacturing industries are discharging toxic and non-biodegradable azo dyes, such as methyl orange, into the environment (Daneshvar et al. 2003). Of the total world production of dyes, up to 20% is lost during industrial processing, causing environmental pollution and contributing to eutrophication that affects aquatic life (Konstantinou and Albanis 2004). Current methods used to treat these effluents are mainly physicochemical, causing a disposal issue for the sludge residue. For example, chemical precipitation and separation of pollutants, electrocoagulation and elimination by adsorption do not destroy the contaminants: they only transfer them to solids which are primarily disposed of into landfills (Daneshvar et al. 2003). Applying nanotechnology to dye degradation shows great potential, as nanoparticles can chemically react with the dyes to form non-toxic products that may require no removal (Biswas and Wu 2005). Photocatalysis is a technique utilizing nanotechnology under thorough study now (Ahmad et al. 2015; Meng et al. 2014; Meng and Ugaz 2015).

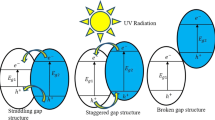

The process of photocatalysis is powered by photons that match or exceed the band gap energy of a given semiconductor (Saleh and Gupta 2012). An electron in its valence band (VB) is excited to the conduction band (CB), leaving a positive hole in the VB that forms a hydroxyl radical with the hydroxyl ion in water, which is then available for oxidation. Meanwhile, the excited electron reduces oxygen in the CB, which can also act as an oxidizing agent (Saleh and Gupta 2012). However, the photo-generated electrons are unstable in the excited state, thus can easily recombine to their respective holes. This process dissipates the input light energy and results in low-efficiency photocatalysis. Therefore, the development of a more efficient photocatalyst is an important consideration (Saleh and Gupta 2012; Dai et al. 2014; Sakthivel et al. 2003; Ahmad et al. 2015).

Titanium dioxide has been extensively studied as a photocatalyst due to its physical and chemical stability, non-toxicity, low cost, and insolubility under various conditions (Saleh and Gupta 2012). TiO2 is a semiconductor oxide with a high band gap energy of 3.2 eV, allowing pollutant degradation when exposed to high energy light. Similarly, zinc oxide also possesses wider band gap (3.37 eV) than TiO2, as well as higher electron mobility (Dai et al. 2014). While both materials show great potential, they alone do not operate with high photocatalytic efficiency due to electron/hole pair recombination (Dai et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2016).

Strategies to improve the photocatalytic performance of these metal oxides have been widely tested over the past decade (Dai et al. 2014; Konstantinou and Albanis 2004; Saleh and Gupta 2012). For example, altering the textural design, doping, and forming semiconductor composites have been examined. One particular focus of research is the utilization of graphene in combination with semiconductor photocatalysts to act as an electron-transfer medium to reduce recombination (Dai et al. 2014; Nguyen-Phan et al. 2011). There are reports on the performance of nanocomposites of graphene oxide (GO) and TiO2; however, little work has been done with GO–ZnO, GO–TiO2 at different concentrations, composite ratios, and size. In the present study, photocatalytic degradation efficiencies of nanomaterials in pristine (TiO2, ZnO) and composite (ZnO–TiO2, GO–TiO2, GO–ZnO, GO–ZnO–TiO2) form were investigated for the degradation of methyl orange dye under visible light irradiation. Further, the effect of nanoparticle loading, size, and composition were also studied.

Materials and methods

The primary objective was to study the photocatalytic activity of engineered TiO2, ZnO and GO nanoparticle/composite. Details of the experimental plan are described in the following sections.

Synthesis and characterization of nanomaterials

In the present study, we tested ZnO, TiO2 and graphene oxide nanomaterials.

TiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized via hydrothermal reaction of titanium alkoxide stabilized in acidic ethanol–water mixture (Chae et al. 2003). A precursor, titanium isopropoxide (0.02 M; 97% Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was added to ethanol/water (1:8) solution and pH was adjusted to 0.7 using nitric acid. Then the solution was kept on stirring for 4 h at room temperature followed by hydrothermal reaction at 240 °C. The crystallized TiO2 nanoparticles were then obtained as a colloidal suspension.

ZnO nanoparticles were prepared by the sol–gel method (Zak et al. 2016). In brief, 5 g of starch (capping agent) was dissolved in 75 mL of deionized (DI) water at 75 °C and stirred for 30 min. Then, 11.2 g of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O was dissolved in DI water, stirred for 30 min, and added to the starch solution. The mixture was then incubated and stirred for 10 h at 80 °C. ZnO nanoparticles were obtained after the powder product was calcined for 5 h at 500 °C.

A modified Hummer’s method (Wang et al. 2012; Song et al. 2014) was used to synthesize GO, and functional groups (e.g., epoxy, hydroxyl, carboxyl) on the surface allowed for its dispersion in polar solvents including water. In brief, 50 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) was added into a beaker containing 2 g of graphite (45 µm, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) at room temperature. The beaker was cooled to nearly 0 °C using an ice bath. Six grams of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) was then slowly added to the above mixture while it was allowed to warm to room temperature. The suspension was stirred for 2 h at 35 °C. After the suspension was cooled in an ice bath, it was diluted by 350 mL of deionized (DI) water. Then, hydrogen peroxide aqueous solution (H2O2, 30%) was added until the gas evolution ceased to reduce residual permanganate. The suspension was then filtered, washed by DI water, and dried at room temperature for 24 h to obtain brownish graphite oxide powder. The dry powder was dispersed in DI water and sonicated for 3 h to get exfoliated single layer graphene oxide nanosheets. The suspension was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 min, and the supernatant was used for the experiment.

The synthesized nanomaterials were characterized for the size and morphology. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI Technai G2 Spirit) was used to determine the diameters and structure of the synthesized nanoparticles.

Preparation of nanomaterial solutions and dye suspensions

Nanomaterial/composite solutions were prepared at different concentration ratios to test their effects on photocatalytic performance. The first nanocomposite material was prepared by mixing 2 mL each of the 1000 ppm TiO2, ZnO, and GO suspensions. The solution was then sonicated for 30 min before use. The TiO2/ZnO, TiO2/GO, and ZnO/GO nanocomposites were prepared by mixing 5 mL of each component suspension, and again, sonicating for 30 min before use. Finally, the ZnO/GO composite with a 5:1 and 10:1 ratio was prepared by mixing 5 or 10 mL of ZnO suspension to the GO suspension. All the nanomaterial/nanocomposite solution were sonicated before used to ensure the uniform dispersion of the material in the solvent (water).

To perform the photocatalytic activity, methyl orange dye was used as a base in this study. The dye was obtained from commercial sources (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA; MW: 327.33) as analytical reagent grade. Dye solutions of requisite concentration have been prepared by proper dilution from a stock solution of 1000 mg/L concentration.

Photocatalytic performance tests and its efficiency

Photocatalytic performance of the nanoparticles/composites was tested using Xe-lamp as a light source (450 W Xe-arc, 686 nm wavelength). An experimental scheme is shown in Fig. 1. A 1000-ppm stock TiO2 suspension (5 mL) was added to 25 mL of MO (50, 75, and 100 ppm) solution on a stir plate. The solution was kept stirred for 45 min in the dark on 60 rpm to ensure adsorption equilibrium. Samples were withdrawn at every 15 min before the lamp was turned on to study adsorption of dye in the dark. The lamp was turned on when the adsorption equilibrium was attained. Distance between the sample and lamp was 5 cm. Samples were then withdrawn every 20 min, and the solution was exposed to the light for a total of 120 min. The samples were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 6 min, and then supernatant was analyzed using Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer against the standard calibration curve for methyl orange at λ max = 480 nm. Time-concentration profiles were prepared to analyze the degradation of dye. All the experiments were performed at initial pH 4.0, and room temperature (22 ± 2 °C). The same procedure was repeated for ZnO nanoparticles, GO–ZnO, ZnO–TiO2, GO–TiO2 and ZnO–GO–TiO2. Further, activity was also tested for different sizes of ZnO.

Experimental set-up. A scheme showing nanoparticles (NPs), TiO2/ZnO/GO or nanocomposites (NCs), GO–ZnO/GO–TiO2/GO–ZnO–TiO2/ZnO–TiO2 mixed with methyl orange (MO) dye. The solution was exposed to visible light (source: Xe-Arch lamp, 450 W), and kept stirring during light exposure. Samples were taken at various intervals and photocatalytic activity was measured by UV–vis absorption spectroscopy

Results and discussions

The nanoparticles used in the present study were synthesized using the previously established method (Chae et al. 2003; Song et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2012; Zak et al. 2016). The synthesized particles were characterized for their morphological investigation using TEM (Fig. 2). Metal oxide (TiO2 and ZnO) particles were of 25 ± 2.6 nm, and graphene oxide nanosheets were of 2–3 µm in length and had less than 4 layers of thickness. In addition, ZnO nanoparticles of 15 and 80 nm were also synthesized to test the effect of size on the photocatalytic efficiency.

The synthesized and characterized nanomaterials were mixed in the methyl orange solution of various concentrations (50–100 ppm) to understand the co-relation of the initial concentration of methyl orange and photocatalytic activity. The solution was exposed to the light source as described in the experimental section. There were two phases of degradation in each cases—one by adsorption in the dark (up to 45 min) and the other by photocatalysis under illumination (45–120 min). For TiO2, in both the phases, removal of dye increased with increase in initial concentration of MO dye from 50 to 100 ppm (Fig. 3a). For ZnO (Fig. 3b), the trend reversed after the dark adsorption phase was over; 40% of the initial 50 ppm dye was removed whereas the removal for 75 and 100 ppm were 38 and 25%, respectively. Though adsorption is the pre-requisite of photocatalysis and more adsorption should lead to more photocatalysis, the difficulty of penetration of light through higher concentration of dye solution should also be considered. Therefore, in our further tests of other parameters, including the preliminary test with graphene oxide (Fig. 3c), we used a constant 50-ppm concentration of methyl orange solution.

Effect of methyl orange (MO) concentration on the photocatalytic performance of nanoparticles. Three concentrations (up to 100 ppm) of the MO were tested with TiO2, ZnO and GO nanostructure. Tests with TiO2 (a) and ZnO (b) showed higher concentration limits of photocatalytic activity, and graphene (c) was tested for its base photocatalytic activity for further experiments with optimum MO concentration (50 ppm)

Among the tested materials, ZnO nanoparticles perform as a better photocatalyst in visible light, removing more methyl orange dye in the total 120 min of reaction (Fig. 4). This higher performance is likely due to the ability of ZnO to absorb greater quanta of the visible light, promoting more electrons to higher energy states (Sakthivel et al. 2003; Sun et al. 2015). In addition, ZnO has a wide band gap of 3.37 eV, greater than that of TiO2. Thus, fewer electrons are likely to fall back to the valence band once excited, resulting in less energy loss and higher dye degradation efficiency (Saleh and Gupta 2012). Both ZnO and TiO2 were better photocatalysts than GO, as GO is neither a semiconductor nor has a large band gap (Nguyen-Phan et al. 2011). While it overall only removed 5.9% of the MO dye, 2/3 of this degradation was solely from adsorption. These results suggest that combining the efficient adsorption properties of GO with the efficient photocatalytic properties of ZnO could enhance overall efficiency.

Because the size of nanoparticle has the key factor for the photocatalytic efficiency, the different sizes (15–80 nm) of ZnO nanoparticles were synthesized and tested for their photocatalytic efficiency. Results showed that 25 nm ZnO was the most effective in photocatalytic degradation, removing a total of 40% of the dye in 120 min (Fig. 5). The activity is likely due to the high surface area to volume ratio of the smaller particles, increasing the exposure area of the dye to be degraded. The even smaller 15–20 nm particles were similar in efficiency, 38.6%, but performed better with adsorption than as a catalyst. Higher particle size (50–80 nm) showed less dye degradation (5.9%) than 15 and 25 nm ZnO nanoparticles. Using the 25 nm ZnO nanoparticles, the performance of nanocomposites of the various materials in different volumetric ratios was tested.

The nanostructure of oxide nanoparticles (TiO2, ZnO and GO) was tested as individuals and in combination to understand their synergetic efficiency. It was observed that TiO2/ZnO nanocomposite was better at removing methyl orange than TiO2 as an individual, but not as efficient as ZnO. The composite of TiO2/GO; however, was less efficient than both the TiO2/ZnO composite and TiO2 alone, removing only 13.5% of the dye (Fig. 6). While the GO containing composite should increase the efficiency according to the proposed mechanism where GO act as a charge carrier. Its low degradation is due to the decrease in total TiO2 in the composite. As it was synthesized in a 1:1 ratio, the composite contained half the volume of TiO2 than the TiO2 catalyst alone. GO as an individual does not act as a good photocatalyst, therefore, combining it with TiO2 decreases the total photocatalytic action. GO may also be interfering physically with the TiO2 in solution: GO may absorb some of the visible light, resulting in lost light for TiO2. GO could also be acting as a recombination platform for TiO2 instead of a conducting plane for electrons, further worsening photocatalytic performance (Nguyen-Phan et al. 2011).

Relative analyses of photocatalytic efficiency. Nanostructures (TiO2, ZnO, and GO) and nanocomposites (TiO2–ZnO; TiO2–GO; ZnO–GO; TiO2–ZnO–GO) were tested for the methyl orange degradation efficiency in the presence of light (dark: 45 min; light exposure: 120 min). The composite of TiO2–ZnO–GO showed the best photocatalytic activity for the materials tested (in 1:1 ratios by volume)

The TiO2/ZnO/GO nanocomposite resulted in an increase in efficiency from 40% (that of ZnO) to about 44.2% (Fig. 6). While this may support the idea that graphene oxide acts as a charge carrier to reduce the amount of electron recombination, this is a relatively small improvement (Nguyen-Phan et al. 2011; Jiang et al. 2016). The ratio of GO to the photocatalyst materials may again have an impact, as the composite has a 2:1 ratio of the photocatalyst to GO (Fig. 6). While there were equal concentrations of the three materials in the composite, increasing the amount of photocatalyst compared to GO could increase photocatalytic activity, while the large surface area of GO could still act as the charge carrier surface (Jiang et al. 2015, 2016; Nguyen-Phan et al. 2011). Another enhancement in performance could be made by solely combining ZnO and GO, as ZnO was shown to be more efficient than TiO2. (Dai et al. 2014) Like the TiO2/GO composite, ZnO/GO only removed 15.3% of the MO dye. By increasing the ratio of a photocatalyst in the composite (ZnO:GO) from 1:1 to 5:1, a higher photocatalytic efficiency was achieved, removing 53.8% of the dye. Increasing the ratio once more to 10:1, 57.7% of the MO dye was removed (Fig. 7).

Effect of ZnO:GO ratio. An independent test was carried out to understand the effect of the ZnO to GO ratio as ZnO performed better than TiO2 nanoparticles of the same size (Fig. 4). It was observed that increased ZnO:GO ratio enhances photocatalytic efficiency thus more effectively degrades the dye

Conclusions

Titanium dioxide (TiO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), and graphene oxide (GO) were synthesized, characterized, and applied for adsorptive and photocatalytic removal of methyl orange (MO) dye. It was found that TiO2 better removes dye through adsorption at higher initial concentrations of MO, but better removes the dye through photocatalysis at lower initial concentrations. With this, the removal of MO by TiO2 was compared to that by ZnO and GO, all at a lower initial concentration of dye. ZnO degraded the most dye, followed by TiO2 then GO. The effect of the size of a particle on photocatalytic dye degradation was tested by varying the size of ZnO, and the smaller 25 nm diameter particles were found to be most efficient. Finally, TiO2/ZnO/GO, TiO2/ZnO, TiO2/GO, and ZnO/GO nanocomposites were synthesized at 1:1 ratio via sonication and characterized via analytical methods. TiO2/ZnO/GO was the most effective composite for degrading the dye. The degradation increased when the ratio of ZnO to GO was increased in the nanocomposite.

References

Ahmad A, Mohd-Setapar SH, Chuong CS, Khatoon A, Wani WA, Kumar R, Rafatullah M (2015) Recent advances in new generation dye removal technologies: novel search for approaches to reprocess wastewater. RSC Adv 5(39):30801–30818

Biswas P, Wu C-Y (2005) Nanoparticles and the environment. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 55(6):708–746

Chae SY, Park MK, Lee SK, Kim TY, Kim SK, Lee WI (2003) Preparation of size-controlled TiO2 nanoparticles and derivation of optically transparent photocatalytic films. Chem Mater 15(17):3326–3331

Dai K, Lu L, Liang C, Dai J, Zhu G, Liu Z, Liu Q, Zhang Y (2014) Graphene oxide modified ZnO nanorods hybrid with high reusable photocatalytic activity under UV-LED irradiation. Mater Chem Phys 143(3):1410–1416

Daneshvar N, Salari D, Khataee AR (2003) Photocatalytic degradation of azo dye acid red 14 in water: investigation of the effect of operational parameters. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem 157(2003):111–116

Jiang Y, Wang W-N, Liu D, Nie Y, Li W, Wu J, Zhang F, Biswas P, Fortner JD (2015) Engineered crumpled graphene oxide nanocomposite membrane assemblies for advanced water treatment processes. Environ Sci Tech 49(11):6846–6854

Jiang Y, Raliya R, Fortner JD, Biswas P (2016) Graphene oxides in water: correlating morphology and surface chemistry with aggregation behavior. Environ Sci Tech 50:6964–6973

Konstantinou IK, Albanis TA (2004) TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous solution: kinetic and mechanistic investigations: a review. Appl Catal B Environ 49(1):1–14

Liu Z, Zheng H, Yang H, Hao L, Wen L, Xu T, Wu S (2016) mpg-C 3 N 4/anatase TiO2 with reactive 001 facets composites to enhance the photocatalytic activity of organic dye degradation. RSC Adv 6(59):54215–54225

Meng F, Ugaz VM (2015) Instantaneous physico-chemical analysis of suspension-based nanomaterials. Sci Rep 5:9896

Meng F, King MD, Hassan YA, Ugaz VM (2014) Localized fluorescent complexation enables rapid monitoring of airborne nanoparticles. Environ Sci Nano 1:358–366

Nguyen-Phan T-D, Pham VH, Shin EW, Pham H-D, Kim S, Chung JS, Kim EJ, Hur SH (2011) The role of graphene oxide content on the adsorption-enhanced photocatalysis of titanium dioxide/graphene oxide composites. Chem Eng J 170(1):226–232

Sakthivel S, Neppolian B, Shankar M, Arabindoo B, Palanichamy M, Murugesan V (2003) Solar photocatalytic degradation of azo dye: comparison of photocatalytic efficiency of ZnO and TiO2. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells 77:65–82

Saleh TA, Gupta VK (2012) Photo-catalyzed degradation of hazardous dye methyl orange by use of a composite catalyst consisting of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and titanium dioxide. J Colloid Interface Sci 371(1):101–106

Song J, Zinzhi W, Chang C-T (2014) Preparation and characterization of graphene oxide. J Nanomater 2014:1–6

Sun M, Li T, Zhang Z, Wang N, Xie A, Lv X, Wang Y, Wu F, Wang M (2015) Natural biological template for ZnO nanoparticle growth and photocatalytic dye degradation under visible light. RSC Adv 5(103):84406–84409

Wang Y, Liu J, Liu L, Sun DD (2012) Enhancing stability and photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanoparticles by surface modification of graphene oxide. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 12(5):3896–3902

Zak AK, Aziz NSA, Hashim AM, Kordi F (2016) XPS and UV–vis studies of Ga-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by gelatin based sol–gel approach. Ceram Int 42(12):13605–13611

Acknowledgements

This work was performed in part at the Nano Research Facility of Washington University in St. Louis. Partial support by the Lopata Endowment is gratefully acknowledged. CA and SC acknowledge Yao Nie, Washington University in St. Louis for providing training on Xe-lamp. SC thanks the Department of Energy, Environmental and Chemical Engineering Department, Washington University in St. Louis for the travel Grant as a visiting scientist during July–August 2015. CA acknowledges support by a MAGEEP undergraduate summer internship research fellowship from Washington University in St. Louis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Raliya, R., Avery, C., Chakrabarti, S. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange dye by pristine titanium dioxide, zinc oxide, and graphene oxide nanostructures and their composites under visible light irradiation. Appl Nanosci 7, 253–259 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-017-0565-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-017-0565-z