Abstract

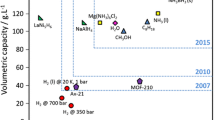

Dry reforming of methane (DRM) is considered a high endothermic reaction with operating temperatures between 700 and 1000 °C to achieve high equilibrium conversion of CH4 and CO2 to the syngas (H2 and CO). The conventional catalysts used for DRM are Ni-based catalysts. However, many of these catalysts suffer from the short longevity due to carbon deposition. This study aims to evaluate the effect of La and Ca as promoters for Ni-based catalysts supported on two different zeolite supports, ZL (A) (BET surface area = 925 m2/g, SiO2/Al2O3 mol ratio = 5.1), and ZL (B) (BET surface area = 730 m2/g, SiO2/Al2O3 mol ratio = 12), for DRM. The physicochemical properties of the prepared catalysts were characterized with XRD, BET, TEM and TGA. These catalysts were tested for DRM in a microtubular reactor at reaction conditions of 700 °C. The catalyst activity results show that the catalysts Ni/ZL (B) and Ca-Ni/ZL (B) give the highest methane conversion (60 %) with less time on stream stability compared with promoted Ni on ZL (A). In contrast, La-containing catalysts, La-Ni/ZL (B), show more time on stream stability with minimum carbon content for the spent catalyst indicating the enhancement of the promoters to the Ni/ZL (A) and (B), but with less catalytic activity performance in terms of methane and carbon dioxide conversions due to rapid catalyst deactivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The large consumption of fossil fuels (coal, gas, and oil) within the past decade by rapid industrial growth has brought several environmental problems such as the rising of global warming gases concentration, including CO2, in air. Recently, the concentration of CO2 has increased by about 1.5 ppm per year which means if there exists about 5.3 × 1021 grams air in the atmosphere, the CO2 increasing rate is about 8 billion tons per year [1–3]. Therefore, reducing the greenhouse gas emission is becoming very important. Carbon dioxide and methane are both greenhouse gases and are available in large amounts which make them interesting reactants for the production of synthesis gas. To reduce the emission of the greenhouse gases into the environment, many efforts have been reported by chemical and biological approach [4]. To date, the catalytic dry reforming of methane (DRM) with carbon dioxide to produce synthesis gas (syngas) has been proposed as one of the most promising technologies to reduce and utilize the CO2 and also to produce syngas H2/CO ratio close to unity which is suitable for methanol, oxo-synthesis and other Fischer–Tropsch syntheses [5–8].

Many investigations on the catalyst design and development for DRM have been focused on screening a new catalyst to reach higher activity and enhanced stability toward sintering, carbon deposition (coking) and metal oxidation [9–14]. However, CO2 reforming of methane has not yet been implemented in the industry because so far there are no active, economic catalysts available and the current development aims to develop a catalyst with high carbon resistance [15].

Many scientific publications reported that all members of group VIII transition metals with the exception of osmium mostly Ni, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ir, and Pt perform a great activity to this reaction [16, 17]. Among these metals, noble metals such as ruthenium and rhodium have been revealed to be the most active and resistant for coke formation [18]. Nevertheless, from economical prospective, scale-up toward industrial level of noble metals is not suitable choice due to their high cost and limited availability comparing to Ni-based catalysts [19], although Ni-based catalysts have a major problem such as carbon formation which possibly forms on the catalyst surface or in the reactor and lead to deactivation of the catalyst or a blocking of the tube of the reactor. Therefore, evaluating different supports [20–22] with the addition of promoters [11, 23–29] has been conducted, with the objective of developing high carbon resistance catalyst.

Recently, although not a focus of attention, it has been revealed that the supported cobalt catalyst demonstrates significant activity for CO2 reforming of methane [30]. However, the catalytic activity is not greater than nickel and the noble metals. Many studies on the supported cobalt catalysts were also reported to find out the better catalytic performance [16]. More recently, Supported nickel catalysts were also investigated over zeolite supports. These catalysts show a good stability against temperature changes [31].

Herein, it is aimed to report the preparation and testing Ni-based catalysts promoted with different promoters such as Lanthanum and Calcium, and supported on zeolites for DRM by carbon dioxide at atmospheric pressure and reaction temperature of 700 °C using a fixed bed reactor. The effect of promoters on catalyst activity and stability will be studied and compared. Various characterization techniques have been employed to compare these catalysts.

Experimental

Catalyst preparation

Two Zeolites Y materials, which were used as the catalyst support throughout this study, Faujasite (FAU) framework type, in their ammonium forms (NH4-Y) were supplied by Zeolyst International Company. They were named as ZL (A) (BET surface area = 925 m2/g, SiO2/Al2O3 mol ratio = 5.1), and ZL (B) (BET surface area = 730 m2/g, SiO2/Al2O3 mol ratio = 12). The nitrate salts of nickel Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (Lobchem, USA) were used as precursor for active metal. Lanthanum nitrate (purity 98 %, BDH, England) and Calcium nitrate (Lobchem, USA) were used as precursors for promoters. A series of six Ni-based catalysts containing 10 wt% of Ni as the active metal, and 10 wt% of La and Ca as promoters were prepared by loading the zeolite supports: ZL (A) and ZL (B) with Ni, La, and Ca precursors by an incipient wetness impregnation method simultaneously. The mixture was dried overnight at 110 °C. All the catalysts were subsequently calcined in air at 500 °C for four hours.

Catalyst characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a Bruker X-ray diffractometer system was employed to examine the crystallinity of the prepared catalysts. Phase identification was carried out using the reference database software.

The BET surface area measurement of the prepared catalysts was collected using Quantachrome Corporation Autosorb by N2 adsorption/desorption method at −196 °C.

The catalyst morphology, structure, and elemental composition of the samples were analyzed with transmission electron microscopy (TEM) technique. We carried out the TEM analysis using the Titan G2 80-300 ST microscope from FEI Company (Hillsboro, OR) that was also equipped with energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) from EDAX (Mahwah, NJ). Prior to the analysis, the TEM specimens were prepared by dispersing the powders in ethanol and then dropping the resulting suspension onto a 400-mesh holey carbon-coated copper (Cu) grid. TEM analysis includes the bright-field TEM (BF-TEM) and high-angle-annular-dark-field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM) techniques in conjunction with EDS to determine the above-mentioned properties of the prepared samples.

The coke gasification profiles were obtained by treating the spent catalysts by air at 973 K using thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA) Perkin-Elmer TG 1700 instrument. A sample of 10 mg of each spent catalyst was loaded in the auto sampler of the TGA and heated up using N2 from room temperature to 973 K at a heating rate of 30 K min−1 followed by a holding time of 1 h in the air environment. The weight changes were monitored and recorded by the TGA‘s software.

Catalytic testing

The dry reforming reaction of CH4 was carried out in a continuous flow reactor, at 1 atm and temperature of 700 °C, with a constant stoichiometric feed mixture of CH4 and CO2 (1:1) and a total flow rate of 40 ml/min. The reaction was performed with 0.6 g of catalyst for each catalytic test. The data were collected every 30 min on stream for 9 h. Reaction products were analyzed by an on-line gas chromatograph (Varian Star 3400 CX). The schematic of the experimental setup and procedure is provided in [32, 33].

Results and discussion

Catalyst characterization

Figure 1 exhibits the XRD patterns for fresh Ni-based catalysts with different promoters, supported on the two zeolites Y, ZL (A) and ZL (B). It can be seen that all observed peaks fit to the FAU structure characterized by intense reflections at 2θ = 6.398, 15.768, and 23.718. The presence of Ni, Ca, and La along with the zeolite Y phase could not be observed indicating the good dispersion of the metals over the structure. Also, the harmony of the number of diffract peaks with regard to HY zeolite confirms that no crystalline transformation occurred during the metal loading via wet impregnation. Thus, the FAU structure is still preserved for all the Ni-based catalyst samples. However, the intensity of the characteristic peaks changed without any substantial change in the peak positions indicating that some amorphous phases were formed within the zeolite structure after the metal loading. It also indicates that the metal species were existing in the cavities and/or surface of HY (catalyst supported).

Table 1 shows the total surface area of fresh activated Ni-based catalysts. It is apparent from Table 1 that surface area of supported catalysts is decreased after metal loading and catalyst activation which may be attributed that sintering of active metal is responsible of this change. Therefore, the pore channels’ access of zeolite support could be blocked due to these metals’ sintering which decreased the catalyst surface area. In addition, this decreasing in the total surface area could be explained that part of zeolite crystallinity was collapsed to form an amorphous content with lower surface area and meso-porosity during catalyst preparation and activation methods.

Figures 2, 3, 4 and 5 show the TEM micrographs for the different Ni-based catalysts. TEM analysis demonstrated a uniform decoration of Ni/ZL (A) and Ni/ZL (B) particles with La and Ca nanoparticles (NPs). Both BF-TEM and HAADF-STEM electron micrographs revealed high density of dispersed NPs with the average size of about 6 nm. The acquired EDS spectra from these samples contained the peaks at the energies of 3.56 and 7.5 keV, which can be attributed to the Ca-La and Ni-Ka peaks, respectively. Overall, TEM analysis in conjunction with EDS elemental analysis revealed the average size of the NPs as well as their composition.

Catalyst evaluation

A series of Ni-based catalysts with two different supports and promoters were prepared and tested for reaction of methane with CO2. Figures 6, 7, 8 and 9 illustrate the catalytic activity and stability for the different catalysts using a microtubular reactor at reaction conditions of 700 °C, atmospheric pressure, and total flow rate = 40 ml/min (CH4 = 15 ml/min, CO2 = 15 ml/min and N2 = 10 ml/min).

Higher catalytic activity in terms of CH4 and CO2 conversions was observed for the catalyst Ca-Ni/ZL (A) compared to that prepared with La and Ni as shown in Figs. 6 and 7. In contrast, the catalysts Ni/ZL (A) and La-Ni/ZL (A) showed higher time on stream stability at the same reaction conditions. After 30 min of the reaction time, the overall methane conversions were 30, 32 and 50 wt% for the catalysts Ni/ZL (A), La-Ni/ZL (A), and Ca-Ni/ZL (A), respectively. The catalysts Ni/ZL (A) and La-Ni/ZL (A) lost about 5 wt% of their activities, then decreased slowly, with the deactivation rate of 1–2 wt% every 30 min. On the other hand, the deactivation rate for Ca-Ni/ZL (A) catalyst was to some extent more rapid, showed a rapid drop in the activity followed by a constant deactivation rate, which ranges from 5 to 10 wt% every 30 min until the end of the reaction.

Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the catalytic activity and stability for the catalysts Ni/ZL (B), La-Ni/ZL (B), and Ca-Ni/ZL (B). The initial overall methane conversions were 60, 10 and 60 wt%, respectively. The catalysts Ni/ZL (B) and La-Ni/ZL (B) initially lost about 2 wt% of their activities, then decreased rapidly after 90 min on stream, with the deactivation rate ranging between 5 and 10 wt% every 30 min until the reaction terminated after about 5 h (300 min). On the other hand, the deactivation rate for La-Ni/ZL (B) catalyst had slightly slow fall in its activity followed by a constant deactivation rate being reached until the reaction terminated.

It can be seen that the Lanthanum promoter may have moderated the surface acidity of zeolite and might have induced the catalyst surface basicity, thus besides acting as structural stabilizers of the support; it might allow limiting catalyst coking since it is a known promoter of carbon removal from metallic surfaces but produces a decrease in the catalytic activity. However, Calcium promoter increased the catalytic activity of Ni/zeolite during the DRM with less stability compared to Lanthanum-containing catalysts. This indicates that Calcium may have changed the interaction nature between the Ni particles and the zeolite support to generate higher activity for CH4 and CO2 conversions which causes catalysts to deactivate more rapidly compared to Lanthanum-containing catalysts. Moreover, it should be considered that the zeolite supports ZL (A) and ZL (B) have different types of acid sites besides different surface textures which suggests that the support plays an important role in the reaction mechanism even though the highly dispersed and nano-sized active metal particles were obtained for both ZL (A) and ZL (B) series as confirmed by XRD and TEM analysis.

Thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out to quantify the amount of carbon deposited on spent catalysts after being used in the CO2 reforming of methane and results are shown in Figs. 10 and 11.

The TGA results of coke removal in air atmosphere as a gasifying agent are consistent with the activity results of catalysts under methane dry reforming. The highest weight drop (around 25 %) was observed for the Ni catalyst promoted with Ca indicating the drop in CH4 conversion (Fig. 6) was a result of the carbon formation. As clearly seen in Fig. 11, the weight drop during the heating from 50 °C until 700 °C was a result of the moisture desorption and its content was below 22 % by weight for all catalysts. After removing the moisture, the weight drop was not significant and the order of the catalyst in terms of carbon content can be suggested as 10 % La-Ni-ZL (B) > 10 % Ca- Ni-ZL(B) > 10 % Ni-ZL (B), this observation is consistent with catalyst activity as illustrated in Fig. 8 (Fig. 12).

Conclusion

A series of Ni-based catalysts supported on two Y different zeolite supports in terms of Si/Al ration and surface texture and containing Lanthanum and Calcium as promoters were prepared by wet impregnation method and tested for DRM by carbon dioxide in a microtubular reactor at temperature of 700 °C, and at atmospheric pressure. In general, it was found that the catalysts Ni/ZL (B) and Ca-Ni/ZL (B) give the highest methane conversion with less time on stream stability compared to promoted Ni on/ZL (A). On the other hand, La-containing catalyst La-Ni/ZL (A) and (B) shows more time on stream stability with less catalytic activity performance in terms of methane and carbon dioxide conversions. This catalytic behavior is faithfully related to the nature of metal–support interaction in the presence of different promoters and supports.

References

Baiker A (2000) Utilization of carbon dioxide in heterogeneous catalytic synthesis. Appl Organomet Chem 14:751

Omae I (2006) Aspects of carbon dioxide utilization. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Carbon Dioxide Utilization. Catal Today 115:33

Meessen JH, Petersen H (2003) Ullmann’s encyclopedia of industrial chemistry, vol 37, 3rd edn. Wiley, Weinheim

Choi MJ, Cho DH (2008) Research activities on the utilization of carbon dioxide in Korea. Clean Air 36:426

Ruckenstein E, Hu YH (1995) Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over nickel/alkaline earth metal oxide catalysts. Appl Catal A Gen 133:149

Richardson JT, Paripatyadar SA (1990) Carbon dioxide reforming of methane with supported rhodium. Appl Catal 61:293

Ross JRH, Keulen ANJV, Hegarty MES, Seshan K (1996) The catalytic conversion of natural gas to useful products. Catal Today 30:193

Fischer F, Tropsch H (1928) Conversion of Methane into Hydrogen and Carbon Monoxide. Brennst Chem 3:39

Juan-Juan J, Roman-Martinez MC, Illan-Gomez MJ (2009) Nickel catalyst activation in the carbon dioxide reforming of methane: effect of pretreatments. Appl Catal A 359:27

Zheng B, Jianhua Y, Xiaodong L, Yong C, Kefa C (2008) Plasma assisted dry methane reforming using gliding arc gas discharge: effect of feed gases proportion. Int J Hydrog Energy 33:5545

Luna AE, Iriarte ME (2008) Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over a metal modified Ni-Al2O3 catalyst. Appl Catal A 343:10

Safariamin M, Tidahy LH, Abi-Aad E, Siffert S, Aboukais A (2009) Dry reforming of methane in the presence of ruthenium-based catalysts. C R Chim 12:748

Therdthianwong S, Therdthianwong A, Siangchin C, Yongprapat S (2008) Synthesis gas production from dry reforming of methane over Ni/Al2O3 stabilized by ZrO2. Int J Hydrog Energy 33:991

Rivas ME, Fierro JLG, Goldwasser, Pietri E, Perez-Zurita MJ, Griboval Constant A, Leclercq G (2008) Structural features and performance of LaNi1−xRhxO3 system for the dry reforming of methane. Appl Catal A 344:10

Hu YH (2009) Solid-solution catalysts for CO2 reforming of methane. Catalysis Today 148:206

Ferreira-Aparicio P, Guerrero-Ruiz A, Rodriguez Ramos I (1998) Comparative study at low and medium reaction temperatures of syngas production by methane reforming with carbon dioxide over silica and alumina supported catalysts. Appl Catal A Gen 170:177

Edwards JH, Maitra AM (1995) The chemistry of methane reforming with carbon dioxide and its current and potential applications. Fuel Process Technol 42:269

Bradforc MCJ, Vannice MA (1999) CO2 Reforming of CH4. Rev Catal Eng Sci 41:1

Ashcroft AT, Cheethan AK, Green MLH, Vernom PDF (1991) Partial oxidation of methane to synthesis gas using carbon dioxide. Nature 352:225

Ruckenstein E, Wang HY (2000) Carbon dioxide reforming of methane to synthesis gas over supported cobalt catalysts. Appl Catal A Gen 204:257

Zhang JG, Wang H, Ajay KD (2007) Development of stable bimetallic catalysts for carbon dioxide reforming of methane. J Catal 249:300–310

Pompeo F, Nichio NN, Souza MMVM, Cesar DV, Ferretti OA, Schmal M (2007) Study of Ni and Pt catalysts supported on α-Al2O3 and ZrO2 applied in methane reforming with CO2. Appl Catal A 316:175–183

Juan-Juan J, Roman-Martinez MC, Illán-Gómez MJ (2004) Catalytic activity and characterization of Ni/Al2O3 and NiK/Al2O3 catalysts for CO2 methane reforming. Appl Catal A 264:169–174

Dias JAC, Assaf JM (2003) Influence of calcium content in Ni/CaO/γ-Al2O3 catalysts for CO2-reforming of methane. Catal Today 85:59–68

Frusteri F, Arena F, Galogero G, Torre T, Parmaliana A (2001) Potassium-enhanced stability of Ni/MgO catalysts in the dry-reforming of methane. Catal Commun 2:49–56

Frusteri F, Spadaro L, Arena F, Chuvilin A (2002) TEM evidence for factors affecting the genesis of carbon species on bare and K-promoted Ni/MgO catalysts during the dry reforming of methane. Carbon 40:1063–1070

Juan-Juan J, Román-Martínez MC, Illán-Gómez MJ (2006) Effect of potassium content in the activity of K-promoted Ni/Al2O3 catalysts for the dry reforming of methane. Appl Catal A 301:9–15

Chen H, Wang C, Yu C, Teng L, Liao P (2004) Carbon dioxide reforming of methane reaction catalyzed by stable nickel copper catalysts. Catal Today 97:173–180

Osaki T, Mori T (2001) Role of Potassium in Carbon-Free CO2 Reforming of Methane on K-Promoted Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts. J Catal 204:89–97

Budiman AW, Song S-H, Chang T-S, Shin C-H, Choi M-J (2012) Dry Reforming of Methane Over Cobalt Catalysts: A Literature Review of Catalyst Development. Catal Surv Asia 16:183–197

Fakeeha AH, Al–Fatesh AS, Abasaeed AE (2012) Ni/Y -Zeolite Catalysts for Carbon Dioxide Reforming of Methane. Adv Mater Res 550–553:325–328

Al-Fatesh A, Fakeeha A, Abasaeed A (2011) Effects of Selected Promoters on Ni/γ-Al2O3 Catalyst Performance in Methane Dry Reforming. Chin J Catal 32:1604

Al-Fatesh A, Ibrahim A, Fakeeha A, Soliman M, Siddiqui M, Abasaeed A (2009) Coke formation during CO2 reforming of CH4 over alumina-supported nickel catalysts. Appl Catal A Gen 364:150

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank KACST for funding of this project. In addition, we thank our colleagues from the KACST and KSU who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted in completing the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Alotaibi, R., Alenazey, F., Alotaibi, F. et al. Ni catalysts with different promoters supported on zeolite for dry reforming of methane. Appl Petrochem Res 5, 329–337 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13203-015-0117-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13203-015-0117-y