Abstract

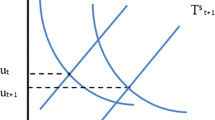

This paper integrates a learning model and two production models with endogenous technical change emphasizing the importance of tacit knowledge capital (KC). Individual business firms may experience diminishing returns to their existing tacit KC. However, when these firms update their tacit KC using the dialectical learning process, they can increase their productivity (output per worker) potentially creating a natural externality in their industry. Because firm-level production innovations cannot be perfectly patented or kept secret, tacit knowledge created by one firm can spill over to the industry leading to increasing returns to tacit KC. A conceptual framework is developed showing that increasing the tacit knowledge base of the firm is needed to foster the technical change required to increase productivity in both the firm and corresponding industry. Causes of diminishing returns to existing tacit KC at the firm level are discussed. Also, some pathways to increasing industrial returns to tacit KC are explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Linking the Cobb-Douglas Production Function to the Solow Growth Model” section is partially adapted from McGahagan (2000) and Woods (2007).

Mathematically, the marginal product of labor \( \left({\mathrm{MP}}_{\mathrm{L}}\right) = \frac{\partial Q}{\partial L} < 0 \).

Mathematically, the marginal product of capital \( \left({\mathrm{MP}}_{\mathrm{K}}\right) = \frac{\partial Q}{\partial K} < 0 \). For example, adding a second computer screen to a computer would initially increase the productivity of the computer operator. However, adding successive computer screens to a single computer will eventually become a distraction to the operator causing a decline in the operator’s productivity and output.

The author recently toured a large manufacturing plant. Production lines were redesigned in an inverted U shape rather than linearly. This increased the field of vision for the assembly worker requiring fewer steps and less time to monitor the production process. The inverted U shape production line also enabled the elimination of an additional production worker. By redesigning the plant, a larger capital/labor ratio per production line improved productivity (output per worker).

Note that physical capital also has the characteristic of being a private, rival good that is excludable.

Mathematically, the marginal product of existing tacit KC \( \left({\mathrm{MP}}_{\mathrm{tkc}}\right) = \kern0.5em \frac{\partial q}{\partial \mathrm{t}\mathrm{k}\mathrm{c}} < 0 \).

Path dependence is exhibited by firms when the behavior of output produced depends on the repeated use of the existing production techniques they follow (Cortright 2001).

Cognitive capture is also referred to as inattentional blindness (see Mack and Rock 2000).

“Using the Dialectical Learning Process to Increase the Tacit Knowledge of the Firm” section is largely adapted from Woods (2012).

Mathematically, \( \frac{\partial Q}{\partial \mathrm{T}\mathrm{K}\mathrm{A}}=A \).

References

Andrade, L., Plowman, D. A., & Duchon, D. (2008). Getting past conflict resolution: a complexity view of conflict. In Management Department Publications (Vol. 10, pp. 23–28). Lincoln: University of Nebraska.

Argyris, C. (1999). On organizational learning (2nd ed.). Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

Bannock, G., Baxter, R. E., & Davis, E. (1998). The penguin dictionary of economics. London: Penguin.

Berger, S. (2013). Making in America: from innovation to market. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Boerner, C. S., Macher, J. T., & Teece, D. I. (2003). A review and assessment of organizational learning in economic theories. In M. Dierkes, A. B. Antal, & J. Child (Eds.), Handbook of organizational learning and knowledge, (Chapter 4). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The second machine age—work, progress and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. New York: W.W. Norton.

Busch, P. (2008). Tacit knowledge in organizational learning. U.S.: IGI Publishing.

Carayannis, E. G. (2001). The strategic management of technological learning. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Cortright, J. (2001). “New growth theory, technology and learning: a practitioners guide”, Reviews of economic development literature and practice, (No. 4), U.S. Economic Development Administration.

Davenport, T., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge: how organizations manage what they know. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

David, P. A., & Foray, D. (2003). Economic fundamentals of the knowledge society. PolicyFutures in Education, 20–49, Education and the Knowledge Economy, special issue.

Derry, S. J. (1996). Cognitive schema theory in the constructivist debate. Educational Psychologist, 31, 163–174.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109–122.

Greenhalgh, C., & Rodgers, M. (2010). Innovation, intellectual property and economic growth. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hau, Y.S., Kim, B. and Lee, H. (2014). “What drives employees to share their tacit knowledge in practice,” Knowledge management research and practice, 1–14.

Hegel, G. W. F. (2010). Science of logic. London: Routledge. originally published in 1812.

Huang, X., Hsieh, P., & He, W. (2014). Expertise dissimilarity and creativity: the contingent roles of tacit and explicit knowledge sharing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 816–830.

Lawson, C., & Lorenz, E. (1999). Collective learning, tacit knowledge and regional innovative capacity. Regional Studies, 33, 305–317.

Mack, A., & Rock, I. (2000). Inattentional blindness. Cambridge: MIT Press.

McFadyen, M. A., & Cannella, A. A., Jr. (2004). Social capital and knowledge creation: diminishing returns of the number and strength of exchange relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 735–746.

McGahagan, T. (2000). The Solow growth model. Johnstown: Department of Economics, University of Pittsburgh.

Nohria, N., & Gulati, R. (1996). Is slack good or bad for innovation. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1245–1264.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5, 14–37.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: how Japanese companies create and the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Parker, J. (2014). “Theories of endogenous growth”, Economics 314 Course book, (Chapter 5). Portland: Department of Economics, Reed College.

Polanyi, M. (1967). The tacit dimension. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94, 1002–37.

Schmidt, W. H. (1974). Conflict a powerful process for [good or bad] change. Management Review, 63, 4–10.

Scott, B.B. (2011). “Organizational learning: a literature review”, Discussion Paper 2011–02, IRC Research Program, Queens University.

Simon, H. A. (1991). Bounded rationality and organizational learning. Organization Science, 2, 125–134.

Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Journal of Political Economy, 70, 65–94.

Woods, J. G. (2007). Creative destruction through the prism of regional economic growth: the California example. In E. G. Carayannis & C. Ziemnowicz (Eds.), Rediscovering Schumpeter—creative destruction evolving into “mode 3”. UK and New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Woods, J. G. (2012). Using cognitive conflict to promote the use of dialectical learning for strategic decision-makers. The learning organization: an international journal, 19, 134–147.

Woods, J.G. (2015). “The effect of technological change on the task structure of jobs and the capital-labor trade-off in U.S. production”, Journal of the knowledge economy. Available [online] at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13132-015-0275-2

Acknowledgments

I thank Brandon Katz for technical research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Woods, J.G. From Decreasing to Increasing Returns: the Role of Tacit Knowledge Capital in Firm Production and Industrial Growth. J Knowl Econ 10, 1482–1496 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-016-0351-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-016-0351-2