Abstract

Poor urban dwellers tend to be disadvantaged in terms of public service delivery, often relying instead on groundwater through self-supply, but their specific needs and opportunities—and own level of responsibility—are seldom on the agenda. The Greater Accra Region of Ghana and the country as a whole serve to illustrate many interconnected aspects of urbanization, inadequate service provision, peri-urban dwellers’ conditions, private actors’ involvement and user preferences for packaged water. Based on interviews and a household survey covering 300 respondents, this case study aims to provide insights into the water-related practices and preferences of residents in the peri-urban, largely unplanned township of Dodowa on the Accra Plains in Ghana and to discuss implications of low accountability and a complex governance landscape on the understanding of reliance on groundwater. Self-sufficient from wells and boreholes until a distribution network expansion, Dodowa residents today take a “combinator approach” to access water from different sources. The findings suggest that piped water supplies just over half the population, while the District Assembly and individuals add ever-more groundwater abstraction points. Sachet water completes the picture of a low-income area that is comparatively well off in terms of water access. However, with parallel bodies tasked with water provisioning and governance, the reliance on wells and boreholes among poor (peri-) urban users has for long been lost in aggregate statistics, making those accountable unresponsive to strategic planning requirements for groundwater as a resource, and to those using it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While the water community is moving beyond the simple classification of water sources as improved or unimproved and striving instead to ensure access for all and sustainable management of our shared water resources under Agenda 2030, it remains clear that the state alone is unable to provide regulated, piped supplies to everyone. This is partly associated with trends in urbanization, where rapid, unplanned or inadequately managed expansion leads to sprawl and unequal sharing of the benefits of development (cf. UN DESA 2014). This global process involves stretching the built-up area and spilling over the fringe, moving administrative boundaries and habitations outwards. The conventional urban–rural divide has since long given way to include also a third type of landscape: the peri-urban area, a transitional zone between the city and its hinterland (Rauws and de Roo 2011). However, as shown by Allen et al. (2006), peri-urban dwellers—in particular the poor—are often left to their own devices when it comes to realizing their human rights to water and sanitation because their needs, practices and private solutions remain “invisible” to the public sector.

Residents in low-income and unplanned urban areas in Sub-Saharan Africa belong to the disadvantaged group sometimes described as “left behind”. They tend to depend partially or completely on groundwater, often because awareness and cheaper technology allow it, combined with the sheer urgency to source water locally. Organic urbanization, population growth and climate variability exacerbate the need for coping strategies among the poor. Though seldom separated out in the statistics, this water may be supplied through the networked system involving public standpipes, either with aquifers as the sole source or as part of a conjunctive system that also supplies surface water. Groundwater may also be accessed from the community, private vendors or NGO-run kiosks, or through self-supply from own or shared wells and boreholes (Chakava et al. 2014; Grönwall et al. 2010; Okotto et al. 2015).

However, in (peri-) urban locations, groundwater of good quality can be scarce seasonally or geographically and suffer from competing abstraction. Poor operation and maintenance of the infrastructure may render the water inaccessible. The water may be contaminated and cause serious hydro-chemical and/or microbiological health hazards. Emerging anthropogenic pollutants constitute a problem within shallow wells sited in areas of low-cost housing due to inadequate sanitation, household waste disposal, and poor well protection and construction (Sorensen et al. 2015). The quality is generally not monitored once a borehole or well is constructed (Rossiter et al. 2010).

Ghana and Greater Accra serve to illustrate many interconnected aspects of urbanization, inadequate service provision, peri-urban dwellers’ self-supply, private actors’ involvement, and user preferences for packaged water. In turn, there are links—some direct and addressed, others invisible and unacknowledged—with groundwater as a resource, fragmented management of it, and issues with silos in governance processes. It is projected that in 2050, 70 % of Ghana’s population will be urban, from today’s 53 % (UN DESA 2014). This growth is already taking its toll on the capital in terms of water scarcity, intermittent and irregular supply and limits to expansion of services. But—despite slow progress initially—the country’s government succeeded in completing a major policy intervention that became decisive for achieving the Millennium Development Goal on access to water by 2015, namely four projects that added some 300,000 m3 of water per day to the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (Republic of Ghana and UNDP 2015). Two of those were the Kpong Water Supply Expansion and the Kpong Intake Expansion Projects, carried out to improve efficiency and increase supply (Andoh 2015).

One area affected by this partly new water distribution scheme is Dodowa, a low-income township at the northern outskirts of Greater Accra. There is a level of irony in this achievement considering that the residents in Dodowa were self-sufficient on groundwater, accessed in various ways including from the Ghana Water Company, Ltd. (GWCL), before the Kpong Expansion. At a quick glance, it may be presumed that the government and public water utility followed the conventional path, regarding boreholes and wells as an inadequate and transient phase before infrastructure to provide piped water could be actualized. However, the concerned District Assembly has a somewhat different strategy. The case of Dodowa described in this paper begs questions relating to the insights into and value assigned to self-supply, the “governance failure” associated with poor service delivery and the disconnect between the strategic planning/management/governance of groundwater as a resource, and how it is in fact relied on. Applying accountability as the lens through which to analyse certain identified problems in the field of groundwater governance, this paper has two aims: firstly, to provide a picture of user practices and preferences in an area for long depending on groundwater, in order to draw from empirical findings on the individual rather than the structural level. Secondly, to discuss implications of low accountability and a complex governance landscape on the understanding of reliance on groundwater among poor (peri-) urban users.

Methods

This paper focuses on a township that has been selected for investigation of the dependence among urban poor on groundwater and associated challenges as part of a larger study of growing mixed urban areas in Ghana, Uganda and Tanzania. The methods employed involve a review of secondary sources and collection of primary data during field work in 2015. Observations during meandering walks were combined with semi-structured, open-ended interviews with 35 (individual or groups of) respondents, consisting of residents in Dodowa and key informants at the public water utility, the District Assembly, the Water Resources Commission, two local mineral water manufacturers and researchers with the University of Ghana, Legon. Together with the local research team, a household-level survey with 300 consenting respondents was conducted in Dodowa in October and November 2015. Systematic sampling was done at every fifth household by assistants; a pre-tested questionnaire was administered through interviews. Descriptive statistics was used to determine the socio-economic and other factors that affect households’ use of water, and a comparison was made with aggregate, district-level data from the 2010 census. That one and our survey had partly overlapping but also partly different points of departure. Based on previous work, literature reviews and observations in the field our study anticipated that users need to take water from a multitude of sources, where wells and boreholes play an important but somewhat invisible role, and that as of recent, there is a preference for sachet water for drinking. This informed the open-ended interviews and the design of the household survey.

Together, the baseline data collected gives a picture of local water access practices and preferences as well as information on the demographic and socio-economic conditions among end-users. Interviews with officials and researchers added insights into the perception of groundwater as a strategic source. It should be noted that the water utility introduced raised tariffs after the field work was completed, wherefore issues related to this lie outside the scope of this paper.

Water access at the peri-urban frontier

Features of horizontal governance

Dodowa is located on the Accra Plains within the Greater Accra Region, just below the Akwapim-Togo mountain range. Formally a town council, it became the capital of the Shai-Osudoku District, carved out of the Dangme West District, in 2012. Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) reports that the district has the highest incidence of poverty in Greater Accra at a rate of 55.1 %, more than four times the regional average, and also has the highest poverty depth (GSS 2015). In the 2010 census, Dodowa had 12,070 residents and the district 50,224; the population of the district was projected to be 55,741 in 2013 which signifies a substantial growth (GSS 2014; SODA 2015). The migration is pronounced in Dodowa; only a third of our household survey respondents reported being born there, and according to key informants, an increasing number of people live in or settle in Dodowa but commute “to the city”, including other major agglomerations in Greater Accra, for work. Among those surveyed, the average household consisted of five people, with a monthly income of 1022 GH₵ (ca. 265 USD); almost a third was spent on food. The median income was 900₵ GH, and the 20:20 income ratio was 600:1360, pointing to a very low equality gap. The majority of respondents owned their house and had an electricity connection. Just over half of household heads had finished primary or junior high school; a third reported being skilled self-employed. One in ten was engaged in subsistence farming or other agricultural activities, which is low compared with the district in general and reflects Dodowa’s peri-urban rather than rural socio-economic characteristics.

Ghana separates the management arrangements for the provision of water into urban and rural areas/small towns, respectively. As the first step of implementing a Water Sector Restructuring Project in 1993, responsibilities for sanitation and small town water supply were decentralized and moved from the predecessor of the GWCL to the District Assemblies. Those became custodians of systems that are otherwise required to be community-managed. The Community Water and Sanitation Agency (CWSA) provides facilitation and advisory support. The GWCL, a parastatal enterprise converted into a limited liability company in 1999, is responsible for urban areas (GWCL 2016). The Shai-Osudoku District falls under GWCL’s jurisdiction, and the company has a local office in Dodowa, but in a curious state of being lost in transition, the CWSA also assumes responsibility for Dodowa alongside the Shai-Osudoku District Assembly (SODA). As noted by Norström (2009), Accra has no coherent spatial development strategy; its structure plan does not consider the old villages in the fringe zones or areas that have already developed in a haphazard manner without schemes. Typical for the current growth in peri‐urban Accra, Dodowa is characterized by houses ranging from compound earth houses with thatched roofs to modern villas at various stages of completion, the latter signifying a gentrification about to take place.

The country’s Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) has a primary concern to address the interests of the urban poor in relation to the GWCL. According to the Commission’s own research, the poor make up just under half of the total population in urban piped system areas and only 15 % of this group has access to “regulated piped supplies”—either directly or via yard taps. The remainder depend on the so-called secondary and tertiary suppliers or buy by the bucket. PURC’s policy is to promote and support initiatives to help the poor gain a direct connection to the piped supply system, based on its findings that this is the preferred method of water access. Accordingly, the ultimate goal of water sector development is, in PURC’s view, to provide regulated piped supply to as many consumers as possible though this is, admittedly, a very expensive strategy. In terms of cost recovery, an incremental block tariff structure is promoted, taking a pro-poor approach to domestic residential customers with application of a “lifeline” tariff (PURC 2005a; b).

The Water Resources Commission (WRC) of Ghana is tasked with management and regulation of the country’s freshwater resources and administrates water rights under the Water Use Regulations, 2001, and the Drilling Licence and Groundwater Development Regulations, 2006. In Dodowa, the WRC is involved in licensing commercial boreholes and local mineral water companies. Groundwater abstraction for domestic use that does not exceed five L/s is exempted from applying for a permit, but is to be registered with the District Assembly. As found during field work, the traditional Chiefs are to be consulted when a mineral water company wants to establish within their communities.

Being water poor and option rich

If PURC’s point of departure is that pipe-borne water is the desirable outcome for all urban poor dwellers, the CWSA is governed by the National Community Water and Sanitation Standards, according to which there should be one public standpipe per 600 people, a borehole per 300 persons and a hand dug well per 150 persons. The SODA, for its part, lists in its yearly budget a vision for extension of piped water to deprived communities, but also that drilling of boreholes and construction of iron and manganese removal plants (through filtration) should be constructed by affected boreholes to benefit those communities (SODA 2015). Over the past decades, various interventions have focused on extending piped water supply schemes in small towns of the district, often following a formula with high-yielding boreholes and mechanized electric pumps transporting the water to a large overhead tank. From the tank, gravity is used to distribute the stored water to various accessible points (community standpipes), at which users can pay attendants for water. The SODA would hold the water systems in trust for the communities, with the latter encouraged to establish water and sanitation (WATSAN) committees to manage the facilities (cf. Sedegah 2014).

Jenkins (2016) found that only two WATSAN committees remain in Dodowa and that their role and function were not widely known in the communities; residents turned instead to their elected Assemblyman with water-related issues. Field work revealed that the SODA has constructed several boreholes fitted mainly with non-mechanized, child-friendly pumps in communities requesting water supply—six were considered functional at the time of this study, but with high electrical conductivity indicating saltiness. Users also take water from community wells, a few of which dug in the 1960s. Some of what are now GWCL’s boreholes were drilled during the same time, but piped water was only distributed from them from the early 2000s. In an interview with a GWCL representative, it emerged that the company considered treatment chemicals as a large cost—chlorination was only used if laboratory tests showed that the water quality was “less good”.

Including the ones belonging to the public utility there are 9 boreholes and around 45 dug wells in Dodowa. The majority are located in the western part that is underlain by quartzite and by gneissic rock in the east. A number of wells and boreholes have been constructed in the past 5 years, and there are indications that the gentrification results in more private boreholes.

In 2012, the Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor partnership (WSUP) commissioned an analysis of water supply options for low-income consumers in Kumasi, Ghana’s second largest city. No less than eleven different options were identified, divided between in-house, compound and communal solutions, with water tanker and boreholes as additional sources. All had different characteristics and different cost–benefit equations (Noakes and Franceys 2014). Similarly, our research in Dodowa indicated that most of those who use GWCL water (56 % of survey respondents) accessed it on what is locally referred to as a pay-and-fetch basis through a neighbour who acts as a middleman, reselling water for the utility from his or her network connection. This individual is either acting as a registered utility agent, put in charge of a public standpipe for premises without connection or is a regular customer with a service provision contract. In the latter case, the contract may be for metered domestic consumption, but informants told us that the service was mostly categorized as commercial. Thus, three different types of rates apply to those reselling water from the tap, depending on how the GWCL classifies the connection.

The final price charged to the end-users can in turn depend on other factors. Customers taking water from a “commercial” tap should in theory pay vastly more than others, but as respondents seldom knew what kind of GWCL contract applied where they fetch their water, this could not be probed into without some difficulty. One factor that may make the end-users willing to pay more is the convenience of being able to get water at any time of the day. Some resellers had installed storage (poly-) tanks by the network connection and fit it with several taps from which customers could fetch water. However, informants encountered during this study complained that it was only possible to fill the tanks at such occasions when the pressure was good and the water supplied for so long time that all those who had queued up could first fill their containers. One reseller explained that her family had been asked to take charge of the taps at two poly-tanks, which involved clearing the debts of the previous reseller. The informant added that as long as the water was provided regularly, they made a profit from selling it on. Another reseller lamented that when it is raining, people do not buy as much as they would otherwise do and the commercial risk had to be borne by her alone.

The GWCL does not charge a connection fee but levies an estimated cost that arises from every new installation. Regarding piped service to the poor, the challenge is to deliver water mains close enough by the house to facilitate low costs for connecting. The minimum price charged according to a study was a prohibitively GH¢150,000 (Franceys and Gerlach 2006).

The water provisioning alternatives for residents of Dodowa are summed in Table 1:

A local “combinator approach” to water access

We found that the vast majority of the residents in Dodowa must apply what is here termed a “combinator” strategy in their daily quest to fulfil basic needs. Water is fetched, purchased or accessed from a mix of sources, sometimes or always with different purposes in mind. The very local context together with the household’s socio-economic circumstances dictates how end-users diversify as a means to adapt and how water from different sources may be utilized.

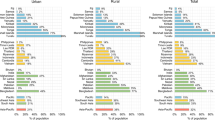

Households were found to take water for all purposes from a variety of sources. The survey asked about the “main” and “second” source. Except for a main source, which everyone had, the majority (55 %) also reported having a second source—for 70 %, this functioned as a back-up, whereas the remainder complemented the main source. As shown in Fig. 1, residents accessed water from six different main sources. Figure 2 shows that more than a third (38 %) self-supplied from dug wells or boreholes, while 56 % accessed piped GWCL water from public or private taps including standpipes.

As for the second source, 73 % of the water was taken from wells or boreholes, with just over half sourced from dug wells. In addition to the main and second sources, essentially all households reported collecting rainwater during wet seasons. Furthermore, 96 % of those surveyed bought purified, packaged sachet water, and a third also bought bottled water.

Our findings seem to differ in several respects from the aggregate numbers for the district, obtained through the 2010 census (cf. GSS 2014), where for other purposes than drinking only 15 % of the urban households used wells and less than one in ten took water from public standpipes, while altogether 62 % had water piped inside or outside the dwelling. In both surveys, the same proportion reported using borehole/pump/tube well (10 %). In other words, respondents in Dodowa 2015 appeared to rely much more on dug wells, especially such previously categorized as “unprotected”, and on standpipes than the residents of the district’s urban areas did collectively in 2010. In most parts of the township, people were able to enjoy relatively good access to groundwater. The water from the local aquifers was used for all purposes, though less and less so for drinking with the advent of sachet water, purchased from mobile vendors in 500-ml bags.

During interviews and informal discussions, it emerged that most people had an opinion about sachet water, which had gained widespread uptake and “become a strong habit” in all social strata in Dodowa in the past decade. The literature on the subject shows that in Accra, sachet water is a response to a gap in urban water provision shaped by chronic shortages when rapid population growth exceeds expansion of the local water infrastructure. In a 2013 survey in a poor community with “paradoxical” good piped water access, convenience was given as the top reason for buying sachets (43 %), followed by “better quality” [than GWCL water, presumably] (23 %) (Stoler et al. 2012b, 2015b). The Food and Drugs Authority registers sachet producers and monitors the raw water treatment; use of sachets has been associated with higher levels of self-reported overall health in women and lower likelihood of diarrhoea in children, meaning that the urban poor may reap an unintended health advantage as sachets replace the consumption of stored water that is often cross-contaminated in the home (Stoler et al. 2012a). Highly reputed brands have been found to be generally coliform-free, but the sachet water production is prone to development of bio-film and emergence of potentially pathogenic microorganisms such as Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, which presents a risk to immune-compromised populations (Stoler et al. 2015a).

Our survey suggests that most (60 %) opted for sachet water because it was perceived as cleaner or safer, whereas taste was referred to among a third of those surveyed as a reason for buying it. Only 8 % cited another reason, including it being cold/chilled. However, in open-ended interviews, motives such as “people have got more money today, they want to show off” came out strongly. Though inconclusive in this respect, our empirical findings indicate that few respondents resorted to sachets and/or bottled water as the only source of drinking water. The majority of those surveyed considered the water obtained from their main source as fit for drinking (75 %) and for cooking (97 %), respectively. Only one in five expressed dissatisfaction with the water for having bad taste, being salty or dirty. Furthermore, 8 out of 10 did not treat their water at point of use, 88 % of whom saying they felt that “there’s no need”.

A GWCL reseller expressed her being happy that the utility does no longer provide borehole water, as it was very salty and would not let the soap lather. However, there was no consensus on this view: the vast majority of people interviewed said that they and their neighbours drink the water from it but also buy sachet water. No survey respondents using GWCL water reported that they found it salty, but those interviewed who had access to either a private or a public tap had diverse opinions. For instance, a respondent born in Dodowa held that her water, taken from a public standpipe outside, was salty and “more so today than it used to be. Sometimes it tastes like in the old days”, while in a house across the street with a yard tap, an old man said that “the taste is different now, less salty”. Likewise, the views on how regular the GCWL water supply was and whether there had been any changes in this respect more lately differed. Perceptions of salty taste is individual, but it was perhaps telling that so few of the residents interviewed felt well informed about the water provider’s shift in sourcing water from local boreholes to the Volta River via the Kpong treatment plant. It is not unreasonable to believe that people’s memory may be short: had the survey been conducted while the GWCL still distributed groundwater in the network, many more may have remarked on its saltiness. In short—respondents’ conceptualization about the quality of their water was found on personal experiences and opinions, but does not necessarily mean that it would pass the World Health Organization’s tests.

Public utility takes a turn

Dodowa is located at the foothills of a mountain range. It is built on strongly metamorphosed sediments characterized by gneiss, quartzite and sandstone, with poorly permeable low-yielding weathered and/or fractured aquifers (Kortatsi 2006). From mechanized boreholes ranging from 15 to 80 m depth, the GWCL used to distribute water three times per week in Dodowa. This water did not undergo advanced treatment, if any at all. Chlorination was seen as sufficient, despite users complaining about saltiness, high iron content and soaps not lathering. At water supply interventions elsewhere in the district, NGOs installed iron removal plants at boreholes (cf. Sedegah 2014) and some individuals had invested in such also in Dodowa. At the local mineral water companies, key informants revealed that the groundwater underwent reverse osmosis as one of several steps to treat it. Neither at those companies nor at the GWCL did it seem as if there was a comprehensive picture of the chemical quality of the raw water and what treatment was optimal. No measures for aquifer recharge were seen as required; the boreholes were always yielding.

At the end of 2014, GWCL’s abstraction and distribution from its six boreholes in Dodowa was discontinued because water was instead supplied from the Volta via the Akosombo Dam and the Kpong treatment plant. The Kpong expansion projects involve a new water plant, power substations, transmission pipelines, new reservoirs, pumps and booster stations, constructed by international companies such as Siemens and China Ghazouba Group, funded partly by Israel and the Netherlands and partly with a loan from the Bank of China. Upon completion of all phases, the projects aim to benefit up to 3 million people in almost 70 communities in Greater Accra and the adjacent eastern region (Government of Ghana 2016; Modern Ghana 2014).

A year after the surface water began flowing in the pipes in Dodowa, there were complaints over intermittent supplies. Key informants among GWCL employees had different pictures of whether water “from the Kpong” was only meant to supplement the Dodowa water supply, as the majority of the piped water should be coming from its boreholes, or if the purpose was to cease with groundwater distribution (Jenkins 2016). The company blamed the acute water scarcity on, among other things, the dry season, polluted water bodies and construction works. People in the Accra region are accustomed to the water supply deficit and the utility rationing as a response, and the years 2015–2016 were characterized by the El Niño–Southern Oscillation phenomenon and associated with drought in Ghana. Nonetheless, water shortage has, in the service delivery discourse, for long been understood in terms of governance failure.

To govern or not to govern?

Notes on (ground) water governance and accountability

“Governance” is here understood as the multitude of actors, institutions and processes by which decisions are made. The paradigm of governance, as well as the idea of inalienable human rights, implicitly departs from there being a state, more or less welfare-oriented, that is ultimately responsible and answerable to each and every citizen via appointed bodies. This idea permeates the normative recipes for “good” and “effective” water governance from many think tanks and policy institutes. According to the World Bank, governance rests on two core values, inclusiveness and accountability, the latter meaning to ensure that those in authority answer to the group they serve if things go wrong, and are credited when things go well (Bucknall 2006). Clear roles and responsibilities of all actors involved are seen as critical for improving the sustainability of service delivery; “accountable actors” provide and demand better governance (UNDP Water Governance Facility and UNICEF 2015). Lastly, here, mapping of institutional roles and responsibilities is recommended to lay bare issues of unclear, overlapping and fragmented areas and functions, in particular where interdependencies between many public agencies must be managed (OECD 2011).

Drawing from Lockwood et al. (2010: 993), accountability is seen as referring to “(a) the allocation and acceptance of responsibility for decisions and actions and (b) the demonstration of whether and how these responsibilities have been met”. Clearly, the water provisioning and groundwater resource management in Dodowa suffers from it being a largely unplanned, mainly low-income peri-urban area endowed with five administrative bodies—the GWCL, PURC, SODA, CWSA and WRC—having partly overlapping responsibilities. Badly managed multi-level (or as here, horizontal and parallel) governance has inherent challenges and lack of integration is one. Uncoordinated decision-making and limited capacities are others. The GWCL is answerable to its customers but only admits accountability to persons with a direct customer relation to it; end-users who buy water from a reseller cannot approach the utility to make a complaint or request information about the water supply or the raw water source. It also does not involve end-users in decisions to ensure stakeholder participation. The PURC, in its role as the sector regulator, consults with the Consumer Rights Protection Agency and different types of organizations before approving tariff adjustments, but the interests of re-sellers and those accessing water from them are not addressed upfront; end-users are also not regarded as having legitimate concerns with respect to water sourcing or treatment issues.

GWCL has largely followed PURC’s policies regarding, among other things, cross-subsidies between different user categories, but the tariff blocks have been modified at several occasions to cover increased costs, most recently in December 2015, in effect raising the price for all customers but disproportionately so for the poor. The utility’s Low-Income Support Unit has yet to extend its work to comprise Dodowa. This may be part of the reason why the residents in this township are ill-understood in terms of their water-related practices and preferences. A study of another peri-urban town in Greater Accra found that accessing water services involved a complex assemblage of connections and disconnections, which are negotiated every day through practices embodied in the “chase for water” from a variety of water sources to supplement or “patch up” gaps left by the sporadic water flow of the GWCL (Peloso and Morinville 2014). Being “combinators” by default rather than choice translates into end-users—even GWCL resellers and sachet water vendors—knowing little about the water they are consuming, as in where it is sourced from and what pre-treatment it may have undergone. Many interviewees in Dodowa expressed indifference, which may be a sign of how people there generally do not struggle as much for water as is generally reported in other studies and in newspapers from most parts of Greater Accra, if only comparing with the immediate surroundings. It may also mirror the experience of how resellers turning to the local GWCL office for information, on behalf of their own business and their customers, have repeatedly been told to “be patient”. These resellers often also take a large economic risk in their role as middlemen. Taken together, the responsibility and accountability assumed by the GWCL leave a gap as big as its ability to provide continuous and reliable water supplies.

The complex present state of Dodowa’s water governance is evident also from how people turn to the SODA for “Assembly wells” to be installed. This has resulted in boreholes drilled in the recent 5 years, often motivated with that the GWCL supply is insufficient; the pressure in the pipes is poor or the water too irregular. The benefitting community or clan may entrust a senior person to be in charge, and in some places, this person collects a minor tariff towards future maintenance of the pump. These people are also supposed to take on the responsibility of approaching the SODA at downtimes, but among those interviewed for this study, some remarked that “nothing happens” after reporting dysfunctional boreholes or pumps, or that the water table has sunk during the dry season. The District Assembly’s capacity to manage its boreholes is clearly under-dimensioned; however, the set-up works on the presumption that active communities with WATSAN committees take charge after the facilities are handed over. Communities are supposed to raise funds for training by the CWSA, if its assistance is wanted (cf. Sedegah 2014).

With particular reference to groundwater, Foster et al. (2010) have noted that an effective information and communication system is a critical pillar of any resource governance framework. The principle of accountability is closely intertwined with other fundamental governance tenets—transparency, openness and (access to) information being among them. The capacity of the WRC to monitor or play a proactive role with respect to groundwater is limited; permits are generally approved and renewed without the desired level of evaluations, including Environmental Impact Assessments when such would be required. The SODA does not keep any register over domestic groundwater abstraction. The government and GWCL’s decision to connect Dodowa to the expanded network and trade the local groundwater resources for a centralized solution may have been in the interest of streamlining operations. Economies of scale would also bring down the cost of energy and chemicals for processing and providing safe water. Yet, it is noteworthy that the shift was not accompanied by any higher degree of transparency. It should be in everyone’s interest to ensure that information regarding the distribution of surface water from a modern treatment plant reaches all users and prospective ones.

Notes on self-supply

There is nothing unique or new in public utilities as proxies for the state being unable to supply water adequately, or in a community service delivery model failing. Of larger interest here is that a group in Dodowa, as in many other (peri-) urban areas in Africa and Asia, can self-supply rather than rely on the state or a private party functioning as their main water provider. The paradigms involving good water governance, the human right to water and the Agenda 2030 tend to consider a self-supplying household as underserved and do not provide an all-applicable answer to who is accountable during this supposedly transient stage before it becomes connected to the pipe. In the rural context, self-supply is defined as the improvement to water supplies developed largely or wholly through user investment usually at household level (Workneh and Sutton 2008). Such household initiatives, mainly dug wells and manually drilled ones, are increasingly promoted and made part of Self-Supply Acceleration Programmes (Butterworth et al. 2013). For instance, the Ethiopian federal government has accepted that though family wells are often not protected sufficiently to be considered safe supplies by experts or officials, they are valued and invested in by people with scarce resources because of advantages such as convenience (ibid). But though some 30 % of urban dwellers in a number of Sub-Saharan African cities and towns rely on wells and boreholes (Foster 2009; Grönwall et al. 2010) and, in effect, relieve city planners and decision-makers of allocating surface water sources to this group, their specific needs and opportunities—and own responsibilities—are not on the agenda.

Aggregate statistics and insensitive indicators contribute to making the picture more complex than it has to be. As noted in “A local “combinator approach” to water access” section, our respondents in Dodowa relied much more on dug wells, especially such categorized as “unprotected”, than the average resident of the Shai-Osudoku District’s urban areas did in 2010 when surveyed for the census, whose figures are informing public policy. The direct dependence on groundwater from own wells or those of neighbours thus becomes invisible, much together with the overall abstraction from and potential pollution of the aquifers at stake. It should also be stressed that at the time of the 2010 census, all water distributed in Dodowa (and many other parts of the district and beyond) was sourced from boreholes or wells but without there being any strategic planning or management of the resource base in terms of protection or aquifer rejuvenation efforts. The issue of future sustainable yield does not inform decision-making. Neither do the issues of hydrogeological assessments, water quality monitoring, centralized or point-of-use treatment, or the upgrading of sanitation facilities.

As noted by Butterworth et al. (2013), international policy trends in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) exert considerable influence on attitudes associated with poorly protected sources that do not meet standards and are more likely than not to deliver contaminated water. This is despite the fact that boreholes and “improved” wells often do not provide safe water: infrastructure is prone to breakdown and deterioration over time, and the groundwater may be contaminated from natural and/or anthropogenic sources. Besides, not all water used in the household needs to be of potable standard. Taking into account how sachet water permeates the low-income West African market and has been found to be healthier for residents of water-stressed communities to use sachets in place of poorly stored household drinking water (Stoler et al. 2012a), there are numerous benefits not least to vulnerable groups such as children, women and elderly from the easy access to water that self-supply can provide.

Concluding remarks

While the water community is grappling with how to move progressively towards full realization of the human right to water, via the achievement of safely managed drinking water services—as the indicator for the Sustainable Development Goal target 6.1 is formulated—poor urban dwellers often find themselves muddling through. Their coping strategies involve groundwater from dug and drilled wells in combination with sachet water for drinking purposes, both sources that may be comparatively easily accessible to this group but that are neither regulated nor highly recognized in the service delivery paradigm. At the peri-urban fringe, the groundwater might be of even larger relevance both because of a larger distance from a public utility’s network mains and because the quality is better there than in the city centre. Yet, it often remains outside the realm of the international policy framework and WASH interventions. It also stands clear from this case study that groundwater may not be highly valued by local/regional/national decision-makers in processes involving strategic resource management and allocation planning. The agenda does not seem to contain either self-supply as a small-scale alternative to service delivery, or conjunctive use as a large-scale solution.

The township Dodowa on the Accra Plains is a case in point when discussing universal coverage and water supply systems, basic public services and provisioning models. From having relied fully on water from its own aquifers until the end of 2014 when an expanded distribution network allowed also areas at the fringe to be served from a surface water intake and treatment plant, not much in Dodowa has improved. The supply is as irregular as ever. End-users must apply a combinator approach to access water from numerous sources. Self-supply is common. People may have been pushed to take up sachet water for drinking purposes already a decade back partly because of inferior taste and quality of the local groundwater rather than for convenience (as has been a reason in many other places), but the GWCL would be clueless as to which. It has seemingly considered treatment chemicals as a large and inessential cost, not to mention fitting the boreholes with iron removal filters, and not consulted end-users on the matter. The same approach is still taken by the SODA, which does not provide treatment of the water it supplies because its responsibility is seen as stopping with the construction of the borehole facility. Quality issues aside, though, the District Assembly has stepped in frequently in the recent past to contribute to fill the gap left by the GWCL’s inability to supply. Assembly boreholes play the role that the dug community wells used to—and still do in some areas. But if the state fails, there is always a neighbour with a well within reach in Dodowa, hence the conclusion that poor residents in this peri-urban area are among the luckier in Greater Accra, water access wise.

With regard to the question of governance, this paper has sought to focus on accountability and finds that in the absence of a high score in this respect, the responsible bodies had better compensate those concerned with higher degrees of transparency, openness and involvement beyond tokenism. There are many virtues in, for instance, ensuring that end-users have free and easy access to information that concerns their water sources, especially if their participation in the resource management is ultimately desired. The groundwater in Dodowa is in need of better assessment, and the governing bodies are in need of better monitoring. Further research is imperative to establish under what circumstances this can best take place.

References

Allen A, Davila JD, Hofmann P (2006) The peri-urban water poor: citizens or consumers? Environ Urban 18:333–351. doi:10.1177/0956247806069608

Andoh D (2015) Expansion works on Kpong water plant almost completed. Graphic Online, Accra

Bucknall J (2006) Good governance for good water management. The World Bank Group, Washington

Butterworth J, Sutton S, Mekonta L (2013) Self-supply as a complementary water services delivery model in Ethiopia. Water Altern 6:405–423

Chakava Y, Franceys R, Parker A (2014) Private boreholes for Nairobi’s urban poor: the stop-gap or the solution? Habitat Int 43:108–116. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.01.012

Foster S (2009) Urban water-supply security: making the best use of groundwater to meet the demands of expanding population under climate change. In: Proceedings of the Kampala conference, Groundwater and climate in Africa, vol 334, June 2008, IAHS Publications. https://drstephenfoster.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/e-6-foster-2009.pdf

Foster S, Garduño H, Tuinhof A, Tovey C (2010) Groundwater governance: conceptual framework for assessment of provisions and needs. World Bank, Washington

Franceys F, Gerlach E (eds) (2006) Charging to enter the water shop? DfID KAR 8319. Centre for Water Science, Cranfield University, Cranfield

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) (2014) 2010 Population & housing census: Shai-Osudoku District analytical report. Ghana Statistical Service, Accra

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) (2015) Ghana poverty mapping report. Government of Ghana, Accra

Government of Ghana (2016) Greenbook Ghana: infrastructure. http://greenbookghana.com/infrastructure/

Grönwall J, Mulenga M, McGranahan G (2010) Groundwater, self-supply and poor urban dwellers: a review with case studies, vol 26. IIED, London

GWCL (2016) History of water supply in Ghana. http://www.gwcl.com.gh/pgs/history.php. Accessed 13 May 2016

Jenkins S (2016) Come together, right now, over what? An analysis of the processes of democratization and participatory governance of water and sanitation services in Dodowa, Ghana. Masters thesis, Lund University

Kortatsi BK (2006) Hydrochemical characterization of groundwater in the Accra plains of Ghana. Environ Geol 50:299–311. doi:10.1007/s00254-006-0206-4

Lockwood M, Davidson J, Curtis A, Stratford E, Griffith R (2010) Governance principles for natural resource management. Soc Nat Resour 23:986–1001. doi:10.1080/08941920802178214

Modern Ghana (2014) Israel and the Netherlands fund ATMA Water Project. Modern Ghana, Accra

Noakes C, Franceys R (2014) The urban water supply guide: service delivery options for low-income communities. Water & Sanitation for the Urban Poor (WSUP), London. http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/pdf/outputs/Wsup/Water-Supply-Options-Guide.pdf

Norström A (2009) Water and sanitation in Ghana: focus on Adenta Municipal District in the Greater Accra Region. CIT Urban Water Management, Stockholm. http://www.urbanwater.se/sites/default/files/filer/ghana_background_report_feb09.pdf

OECD (2011) Water Governance in OECD Countries: a multi-level approach. OECD Studies on Water. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi:10.1787/9789264119284-en

Okotto L, Okotto-Okotto J, Price H, Pedley S, Wright J (2015) Socio-economic aspects of domestic groundwater consumption, vending and use in Kisumu, Kenya. Appl Geogr 58:189–197. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.02.009

Peloso M, Morinville C (2014) ‘Chasing for water’: everyday practices of water access in peri-urban Ashaiman, Ghana. Water Altern 7:121–139

Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) (2005a) Urban water tariff policy. Public Utilities Regulatory Commission, Accra

Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) (2005b) Social policy and strategy for water regulation. Public Utilities Regulatory Commission, Accra

Rauws WS, de Roo G (2011) Exploring transitions in the peri-urban area. Plan Theory Pract 12:269–284. doi:10.1080/14649357.2011.581025

Republic of Ghana, UNDP (2015) Ghana millennium development goals: 2015 report. UNDP, Accra

Rossiter HMA, Owusu PA, Awuah E, MacDonald AM, Schäfer AI (2010) Chemical drinking water quality in Ghana: water costs and scope for advanced treatment. Sci Total Environ 408:2378–2386. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.01.053

Sedegah D (2014) Demand responsive approach and its significance for sustainable management of water facilities in the Shai-Osudoku District. Dissertation, University of Ghana, Legon

Shai-Osudoku District Assembly (SODA) (2015) Composite budget of the Shai-Osudoku District assembly. SODA, Republic of Ghana, Dodowa

Sorensen J et al (2015) Emerging contaminants in urban groundwater sources in Africa. Water Res 72:51–63. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2014.08.002

Stoler J, Fink G, Weeks JR, Otoo RA, Ampofo JA, Hill AG (2012a) When urban taps run dry: Sachet water consumption and health effects in low income neighborhoods of Accra. Ghana Health Place 18:250–262. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.020

Stoler J, Weeks JR, Fink G (2012b) Sachet drinking water in Ghana’s Accra-Tema metropolitan area: past, present, and future. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 2:223–240. doi:10.2166/washdev.2012.104

Stoler J, Ahmed H, Frimpong LA, Bello M (2015a) Presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in coliform-free sachet drinking water in Ghana. Food Control 55:242–247. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.02.038

Stoler J, Tutu RA, Winslow K (2015b) Piped water flows but sachet consumption grows: The paradoxical drinking water landscape of an urban slum in Ashaiman. Ghana Habitat Int 47:52–60. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.01.009

UNDP Water Governance Facility, UNICEF (2015) WASH and accountability: explaining the concept. UNDP Water Governance Facility at SIWI and UNICEF, Stockholm

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) (2014) World urbanization prospects: the 2014 revision vol ST/ESA/SER.A/352

Workneh P, Sutton S (2008) National consultative workshop on self-supply: report on presentations, discussions and follow up actions. Paper presented at the Ministry of Water Resources/UNICEF/Water and Sanitation Programme, Addis Ababa

Acknowledgments

The work described above was carried out within the framework of the T-GroUP project, funded by the Department for International Development (DfID), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the National Environmental Research Council (NERC) under the UPGro Programme, NERC Grant Number NE/M008045/1. It draws from a household survey conducted together with Drs Sampson Oduro-Kwarteng and George Lutterodt, with research assistants Janix Asare, Seth Adjei and Francis Andorful. It has further benefitted from findings of and discussions with research team members Drs Jan Willem Foppen and Maryam Nastar, and M.Sc students Shona Jenkins, Obed Minkah and Alimamy Kamara.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Grönwall, J. Self-supply and accountability: to govern or not to govern groundwater for the (peri-) urban poor in Accra, Ghana. Environ Earth Sci 75, 1163 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-5978-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-5978-6