Abstract

Valorisation of municipal organic waste through larval feeding activity of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens, constitutes a potential benefit, especially for low and middle-income countries. Besides waste reduction and stabilisation, the product in form of the last larval stage, the so-called prepupae, offers a valuable additive in animal feed, opening new economic niches for small entrepreneurs in developing countries. We have therefore evaluated the feasibility of the black soldier fly larvae to digest and degrade mixed municipal organic waste in a medium-scale field experiment in Costa Rica, and explored the benefits and limitations of this technology. We achieved an average prepupae production of 252 g/m2/day (wet weight) under favourable conditions. Waste reduction ranged from 65.5 to 78.9% depending on the daily amount of waste added to the experimental unit and presence/absence of a drainage system. Three factors strongly influenced larval yield and waste reduction capacity: (1) high larval mortality due to elevated zinc concentrations in the waste material and anaerobic conditions in the experimental trays; (2) lack of fertile eggs due to zinc poisoning, and (3) limited access to food from stagnating liquid in the experimental trays. This study confirmed the great potential of this fly as a waste manager in low and middle-income countries, but also identified knowledge gaps pertaining to biological larvae requirements (egg hatching rate, moisture tolerance, …) and process design (drainage, rearing facilities, …) to be tackled in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Management of municipal solid waste (MSW) in low and middle-income countries remains a challenging and neglected key issue. Especially in urban and peri-urban areas, the household waste often remains uncollected on streets and drains, thereby attracting disease vectors and causing water blockages [1, 2]. Compared to other waste components, such as glass, metal and paper, the organic fraction, often amounting to 80% of the total municipal waste, is frequently looked upon as a waste fraction without market value and therefore ignored by the informal waste recycling sector [3–5]. Even if collected, MSW typically ends up in a landfill or on a more or less uncontrolled dumpsite where the material decomposes in large heaps under anaerobic conditions. Around 6.8% of Africa’s greenhouse gas emissions are generated by waste activities, primarily methane released from open dumps [6]. To reduce the environmental burden and improve public health, new and financially attractive waste management strategies should be explored and fostered. Similar to the well established recycling and resource recovery sector for inorganic material, such as glass, PET (polyethylene terephthalate) or metal, collection and recovery of municipal organic waste (MOW) can contribute to generate additional value if appropriate valorisation technologies are provided [4].

Examples of CORS technologies (Conversion of Organic Refuse by Saprophages), such as vermicomposting or faecal sludge treatment by the aquatic worm Lumbriculus variegatus, could offer promising alternatives of nutrient recovery from organic waste [7]. Organic waste digestion by the larvae of the black soldier fly (BSF), Hermetia illucens L. (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) is another CORS solution combining nutrient recovery and income generation [8]. The larvae of this non-pest fly feed on and thereby degrade organic material of different origin. Domestic waste, chicken, pig and cow manure and even human excreta were found to be easily processed by the larvae. The 6th instar, the prepupa, migrates from the feed source to pupate and can therefore easily be harvested. Since prepupae contain on average 44% crude protein and 33% fat [9], it is an appropriate alternative to fishmeal in animal feed with a potential market value of 330 USD/tonne dry weight [10]. Conversion of organic waste into high nutritional biomass opens new economic opportunities for municipalities and small entrepreneurs in the MSW sector.

Over the past 20 years, the biology of H. illucens has been studied extensively, especially regarding its use in waste management and protein production [8, 11–13]. Additional research focused on the prepupae’s potential as animal feed [9, 14] and its limitations in waste management [15, 16].

So far, the BSF technology has been successfully tested in the laboratory. However, it remains unclear to which extent the result from laboratory studies can be transferred to the field—a prerequisite for future industrial application of this technology. Sheppard et al. [8] modified a caged layer house fitted with a concrete basin below the cage batteries. The basin allowed easy harvesting and quantification of migrating prepupae. However, it did not allow controlling the feeding rate, and the waste reduction had to be estimated based on the depth of the accumulated chicken droppings. Newton et al. [10] employed the faeces of 12 pigs in an automated system using a dewatering belt to transport the material to the larva treatment bed, thus achieving a 56% of fresh material reduction.

Bioconversion of palm kernel meal into fish feed in the Republic of Guinea and in Indonesia is so far the only known application of the soldier fly technology in tropical countries [17, 18]. However, these cases did not take advantage of the self-harvesting habit of the prepupae. They rather separated the prepupae together with immature larvae from the processed material by filtering and cleaning with water. The aforementioned studies all used homogenous agricultural waste products as feedstock. Application of the results obtained from this past research to the treatment of an inhomogeneous feeding source like municipal organic waste must yet be understood and proven.

The main objective of the present study was consequently to evaluate the feasibility of black soldier fly larvae to digest and degrade mixed municipal organic waste in a medium-scale field experiment in Costa Rica, and to explore the benefits and limitations of this technology. Furthermore, this study will provide recommendations for future research and application of this promising waste treatment process in low and middle-income countries.

Materials and Methods

Study Site

The research study site was located on the campus of the EARTH University (Escuela de Agricultura de la Región Tropical Húmeda) in Guácimo, Costa Rica. The experiments were carried out in a former chicken pen (30 × 8 m) roofed by a corrugated metal sheet and enclosed by a wire net.

Fly Colony

A population of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens L., was maintained in a small green house (2 × 3 × 2.5 m), referred to as “moscario”, roofed with transparent plastic foil fitted with a sun shading net and nylon netted sidewalls. The moscario was placed on a meadow, exposed daily to direct sunlight for about 8 h. In the moscario, a black plastic foil-covered tray (1 × 2 m) containing organic waste was used to attract ovipositing females. The method for collecting eggs was adapted from Tomberlin et al. [12]. Strips of corrugated cardboard (20 × 4 cm, flute opening 2 × 5 mm) were wrapped around skewers and tucked into rings of bamboo (∅ 10–15 cm × 5 cm) placed into the tray. The cardboard strips were collected at least every second day and inserted into nylon covered plastic cups containing wetted rabbit feed. These hatching containers were stored in a dark and warm environment (24°C, 93% RH). Larvae hatched approximately 3 days after oviposition and dropped from the cardboard strips into the wetted rabbit feed. The young larvae were then used at an age of 4–6 days to inoculate the experimental setup. To supply the colony with new adults, ~500 prepupae from every experiment’s harvest were placed into plastic bowls (∅ 35 cm × 10 cm), where they pupated in a mixture of hay, wood shavings and pieces of an empty nest of arboreal termites (Nasutitermes spp). The bowls were covered with nylon netting and the emerging adults released into the moscario.

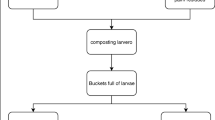

Experimental Setup

The experiments were conducted in trays (80 cm × 200 cm × 30 cm), referred to as “larveros”, built with zinc-coated steel sheets (Fig. 1). For exiting prepupae, two ramps at a 28° angle led from the base plate (100 × 80 cm) to the upper end of each shorter side panel. A plastic pipe (∅ 11 cm × 94 cm) was fixed along the top of this edge. A slit (5 × 80 cm) cut into the pipe allowed migrating soldier fly prepupae to enter and crawl along the pipe leading to downspouts at each end of the pipe from where they fell into harvesting containers.

To avoid ant invasion, the larveros had to be placed on pieces of bamboo (∅ 10–15 cm × 25 cm) standing in water-filled plastic pots. To avoid mosquito breeding, each plastic pot was spiked with a drop of dishwashing detergent.

Organic waste generated by the residents of the EARTH university campus was used for the experiments. The content of several bags of the source-separated organic waste (approximately 20 kg/day) was mixed thoroughly to achieve certain homogeneity and then added to the larveros according to the defined feeding regime.

We designed a full-factorial experiment to assess: (1) the effect of the larvero cover (black sheet or shading net), (2) the effect of food application (surface-fed or mixed with residue) and (3) the effect of food amount (low and high amounts).

The factor “cover” was found to have no influence on the results and was therefore not included into the analysis. The data analysed therefore quasi originated from a full-factorial experiment (two-level, two-factor) with two repetitions.

The factor “application” was chosen to assess whether waste reduction and larval growth benefited from fresh food mixed with already digested material or if surface application led to an enhanced performance from improved access of the larvae to fresh food and increased oxygen supply. Fresh waste was folded manually using a shovel. Regarding the factor “amount”, larveros that were allocated the attribute “low” received on average 1.5 kg of fresh organic waste per day. Larveros with the attribute “high” were fed daily with 4.6 kg of fresh organic waste.

Besides the eight experimental larveros, a ninth larvero, set up and inoculated once with fresh larvae produced from 20 egg clutches, received a surface-fed intermediate amount of food (2.1 kg/day). This larvero was not further inoculated with fresh larvae, its content was mixed thoroughly several times throughout the project period and it served as control for the analysis.

To ensure a coequal establishment of the larval population, all eight experimental larveros were fed daily with 1.1 kg fresh, untreated waste for the first 21 days. During this starting phase, fresh food was placed on top of the larvero’s residual material, independently from the subsequent feeding regime. Six days after the first prepupal crawl-off, the feeding regime was altered according to the assigned factors and run for another 34 days. Feeding and harvesting were conducted at least every second day.

To test the influence of a drainage system on the larvae’s performance, three larveros were equipped with a perforated plastic tube (∅ 5 cm × 80 cm, holes ∅ 6 mm) placed at the bottom of the larvero leading to a tap mounted onto the lower end of the larvero’s side panel. These drained larveros together with three non-drained larveros were fed daily an average of 4.0 kg fresh waste for 23 days.

Samples of waste, prepupae and residue were dried at 80°C for 72 h for analysis and determination of the dry mass. Linear regression and one-way ANOVAs with subsequent Tukey HSD tests were conducted to determine relations and differences between the various treatments (P ≤ 0.05).

Results and Discussion

Life History Traits

We successfully established a stable black soldier fly colony. A mean daytime temperature of 31.8°C provided optimal conditions for reproduction, and H. illucens flies were capable of tolerating a wide range of temperatures in the moscario (recorded range: 15–47°C). Similarly, Booth and Sheppard [19] reported that 99.6% of the oviposition occurred within a temperature range of 27.5–37.5°C. In our experiments, the egg yield (~40 egg clutches daily) from the about 500 adults released to the moscario every day was, however, far lower than expected under the prevailing environmental conditions. We suspected that zinc poisoning, caused by the zinc-coated larveros could be responsible for the reduced fecundity. Residual material in the larveros revealed average zinc concentrations of 4,120 mg/kg dry mass (range: 1,550–8,810 mg/kg) and we must assume that corrosive processes and mechanical mixing activities favoured the release of zinc into the residual material in a magnitude exceeding our expectance. There is no literature describing zinc-related fecundity deficiency in terrestrial dipterans, however, Beyer and Anderson [20] found that zinc concentrations in soil litter exceeding 1,600 mg/kg led to a reduced life span, offspring number and survival rate of the offspring of woodlice, Porcellio scaber (Isopoda: Porcellionidae). Other literature describes the reduced fecundity of ground beetles either fed with zinc-contaminated house fly larvae [21] or raised on contaminated ground [22]. If applicable to dipteran organisms in general and to H. illucens in particular, these zinc findings would explain the low egg yield of the colony. The actual prepupal harvest, which was far lower than expected in relation to the number of young larvae added to the larveros, is also likely to be attributed to the elevated zinc concentration. Each larvero had been inoculated with freshly hatched larvae originating from a daily average of 4.5 egg clutches. Tomberlin et al. [12] found an average of 1,160 eggs per egg clutch deposited into corrugated cardboard similar to the one used in the present study. Taking this number as a measure, a prepupal harvest of 178,000 prepupae would have resulted throughout the 34 monitored days in the present study. However, in the high-fed larveros receiving 4.6 kg of food per day, we harvested only 26,000 prepupae or 6.8 times less than expected. In the low-fed larveros receiving 1.5 kg/day, the yield was even 11.7 smaller than expected. This phenomenon is not only caused by the reduced hatchability of eggs laid by zinc-contaminated females and the overestimated amount of young larvae inoculated as described above, but possibly also due to an increased mortality of young larvae feeding on zinc-contaminated material. Zinc in food offered to house fly larvae is known to lead to a 60% mortality rate in larvae and 70% in pupae. Borowska et al. [23] attribute this increased larval mortality rate to the larvae’s reduced density of haemocytes, an indicator for the fitness of the immune defence in insects. A linear regression revealed that the amount of food and zinc concentration in the residue was strongly related to the prepupal harvest (Tables 1 and 2). Yet, when interpreting this regression analysis, one has to bear in mind that sample size N = 9 was very small, and the correlation between amount of food and zinc concentration accounted to −0.664. Nevertheless, future experimental setups and full-scale treatment facilities should avoid zinc-coated sheeting using plastic or concrete instead.

Prepupal Yield

Average prepupal yield during the last experimental week accounted to 252 g/day (wet weight, SE 23.9) in the high-fed larveros receiving 4.6 kg/day and 134 g/day (wet weight, SE 22.6) in the low-fed larveros (Table 3). Compared to the two high/surface larveros, the residue of the high/mixed larveros revealed a higher zinc concentration, thereby possibly explaining the lower prepupal yield. The undisturbed surface loading probably allowed larvae to feed partially on uncontaminated food, thus leading to a higher prepupal harvest.

During the 55 day experimental study, the larveros never reached a steady state, with the amounts of prepupae harvested still augmenting and showing a strong fluctuation in daily prepupal harvests. To what extent this can be attributed to zinc contamination or to heterogeneity of the municipal organic waste still remains uncertain. As a matter of fact, other studies also showed strong variations in prepupal crawl-off and rarely established a constant and predictable harvest [8, 24, 25]. Days with high prepupal yield were followed by low prepupae production. Interestingly, all the larveros followed a synchronised pattern of high and low harvest, implying an overall trigger for larval migration being either of exogenic (humidity, temperature, solar radiation) or endogenic (pheromones) nature.

Waste Reduction Efficiency

The relative dry weight reduction in the different treatments varied from 66.4 to 78.9% (Table 3). It is not surprising that waste reduction was highest in the larveros receiving less food. However, the effective waste material reduction (effective dry weight eliminated per day) was significantly higher in the larveros receiving a high feeding rate, i.e. 740 g/m2/day if the fresh waste was mixed completely with the residue, and 780 g/m2/day if applied on the surface of the residuum. Despite a relatively low larval density, a fairly high relative dry weight reduction was achieved demonstrating that the larvae were able to cope with the daily amount of waste fed. With a 0.86 larvae/cm2 density, we achieved a daily feeding rate of 507 mg/larva/day, which is far higher than the 61 mg of kitchen waste proposed by Diener et al. [13]. Under ideal environmental conditions and with a 5 larvae/cm2 density, the loading capacity of the system could be a severalfold of the 4.6 kg/day, as fed in the present study.

During the experiments, a considerable amount of stagnating liquid accumulated in the larveros, thus creating an anaerobic, foul-smelling environment. Larvae avoided these areas, causing submerged food to remain untouched. Installation of a drainage system in the larveros improved the waste reduction efficiency from 65.5 to 72.2% for dry weight and from 38.9 to 50.8% for wet weight reduction, though both at a statistically non-significant degree (Sig. = 0.094 and 0.058, respectively). However, the drainage system used in this study revealed some shortcomings: the tap installed to control the effluent often clogged and larvae crawled through the openings. Use of an appropriate filter material (coarse sand, synthetic filter mat) and installation of an s-shaped water seal are possible solutions to these problems.

During the experiments, larvae of the green hover fly, Ornidia obesa F. (Diptera: Syrphidae) were often found among the harvested H. illucens prepupae. They showed the same migratory habit and were of similar shape and weight (208 mg, SE 4.5). However, in comparison to the 252 g/day harvest of H. illucens, the daily O. obesa harvest of 8 g/day is negligible. The fact that O. obesa had been found in decaying material, such as coffee pulp or pig carcasses [26, 27] and apparently with a similar larval development as H. illucens, makes the green hover fly a possible protagonist in organic waste treatment. Further research has to assess its nutritional value and to appraise possible constraints and risk potential for humans and animals.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Despite the zinc contaminated and hostile environment for the larvae in the larveros and subsequent reduced fecundity of the adults, this technology revealed its great potential for organic waste reduction and protein production. Even though the system did not reach a steady state during the observed period, the larveros produced a remarkable average of 252 g (SE 20.2) of fresh prepupae per day and m2 during the last week of the experiment and reduced the dry matter by 68%. Prepupal harvest per digested food, the feed conversion rate (FCR), correlates with the few other medium-scale studies using fly larvae for waste treatment and protein production. However, waste reduction in the present study is far higher than in other studies (Table 4).

Three factors strongly influenced larval yield and waste reduction capacity: (1) lack of fertile eggs due to zinc poisoning; (2) high larval mortality due to the hostile environment in the larveros (zinc concentration, anaerobic conditions) and (3) limited access to food due to stagnating liquid in the larveros. Though elimination of these stumbling blocks is simple, future research will have to concentrate on two main aspects: the biological key factors as well as design and operation of the treatment facility. Enhanced knowledge of the environmental and nutritional requirements of H. illucens will significantly improve resilience of the treatment system. Thanks to the larvae’s natural habit to colonise feed sources undergoing changes in time, H. illucens has developed several peculiarities to warrant survival of the population. During food shortage or unfavourable conditions (oxygen deficiency or low temperatures), the larvae reduce or cease to feed. Under other conditions, when survival of the individual is endangered (e.g. high temperature, toxic conditions), the larvae try to abandon the feed source. For a successful soldier fly treatment system, it is therefore of utmost importance to determine what triggers cessation of food intake or mass migration of immature larvae.

Design and operation of the treatment facility is subject to local context as well as existing habits and requirements. The nature of the waste products and availability of labour and machinery strongly influence construction of the facility. However, the following recommendations are generally applicable: (1) a regular, well-balanced food supply prevents bad odours and guarantees a consistent and efficient feeding activity; (2) a drainage system is required when working with wet material (household waste, pig manure) or in a humid climate and (3) use of a ramp for self-harvesting proved of great value and its further development should be pursued. Based on the aforementioned prerequisites, at least 15 kg of fresh municipal organic waste can be added daily to an area of 1 m2 yielding a prepupal harvest of 0.8–1.0 kg.

References

Diaz, L.F., Savage, G.M., Eggerth, L.L., Golueke, C.G.: Solid waste management for economically developing countries. In: The Internat. Solid Waste and Public Cleansing Association, Copenhagen, Denmark+CalRecovery Incorporated. (1996)

Zurbrügg, C., Rothenberger, S., Vögeli, Y., Diener, S.: Organic solid waste management in a framework of millennium development goals and clean development mechanism. In: Diaz, L.F., Eggerth, L.L., Savage, G.M. (eds.) Management of Solid Wastes in Developing Countries, p. 430. CISA, Padova, Italy (2007)

Ali, A.: Managing the scavengers as a resource. In: Günay Kocasoy, T.A., Nuhoğlu, İ. (eds.) Appropriate Environmental and Solid Waste Management and Technologies for Developing Countries, vol. 1, p. 730. International Solid Waste Association, Bogazici University, Turkish National Committee on Solid Waste, İstanbul (2002)

UN-HABITAT: Solid Waste Management in the World’s Cities. Earthscan, London and Washington, DC (2010)

Ahmed, N., Zurbrugg, C.: Urban organic waste management in Karachi, Pakistan. In: 28th WEDC Conference on Sustainable Environmental Sanitation and Water Services. Kolkata, India (2002), Folder F34 (Pakistan)

Couth, R., Trois, C.: Comparison of waste management activities across Africa with respect to carbon emissions. Paper presented at the Twelfth International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium, S. Margherita di Pula, Cagliari, Italy, 5–9 October (2009)

Elissen, H.J.H.: Sludge reduction by aquatic worms in wastewater treatment with emphasis on the potential application of Lumbriculus variegatus. PhD, Wageningen University, The Netherlands (2007)

Sheppard, D.C., Newton, G.L., Thompson, S.A., Savage, S.: A value-added manure management-system using the black soldier fly. Bioresour. Technol. 50(3), 275–279 (1994)

St-Hilaire, S., Sheppard, D.C., Tomberlin, J.K., Irving, S., Newton, G.L., McGuire, M.A., Mosley, E.E., Hardy, R.W., Sealey, W.: Fly prepupae as a feedstuff for rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. J. World Aquac. Soc. 38(1), 59–67 (2007)

Newton, G.L., Sheppard, D.C., Watson, D.W., Burtle, G.J., Dove, C.R., Tomberlin, J.K., Thelen, E.E.: The black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens, as a manure management/resource recovery tool. In: Symposium on the State of the Science of Animal Manure and Waste Management. San Antonio, Texas, USA, CR, pp. 5–7 (2005)

Tomberlin, J.K., Sheppard, D.C.: Factors influencing mating and oviposition of black soldier flies (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) in a colony. J. Entomol. Sci. 37(4), 345–352 (2002)

Tomberlin, J.K., Sheppard, D.C., Joyce, J.A.: Selected life-history traits of black soldier flies (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) reared on three artificial diets. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 95(3), 379–386 (2002)

Diener, S., Zurbrügg, C., Tockner, K.: Conversion of organic material by black soldier fly larvae-establishing optimal feeding rates. Waste Manag. Res. 27, 603–610 (2009)

Stamer, A.: Erschliessung alternativer proteinquellen zum Fischmehl für Forellenfuttermittel. In: Verband für ökologischen Landbau e.V., Fachabteilung Aquakultur, Gräfelfing, p. 34 (2005)

Diener, S., Zurbrugg, C., Roa Gutiérrez, F., Nguyen, H.D., Morel, A., Koottatep, T., Tockner, K.: Black soldier fly larvae for organic waste treatment—prospects and constraints. Paper presented at the WasteSafe 2011, 2nd International Conference on Solid Waste Management in Developing Countries, Khulna, Bangladesh, 13–15 February (2011)

Erickson, M.C., Islam, M., Sheppard, D.C., Liao, J., Doyle, M.P.: Reduction of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis in chicken manure by larvae of the black soldier fly. J. Food Prot. 67(4), 685–690 (2004)

Hem, S., Toure, S., Sagbla, C., Legendre, M.: Bioconversion of palm kernel meal for aquaculture: experiences from the forest region (Republic of Guinea). Afr. J. Biotech. 7(8), 1192–1198 (2008)

Fléchet, G.: A good example of successful bioconversion—sheet no 309. In: IRD Institut de recherche pour le développement, p. 2 (2008)

Booth, D.C., Sheppard, D.C.: Oviposition of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): eggs, masses, timing, and site characteristics. Environ. Entomol. 13(2), 421–423 (1984)

Beyer, W.N., Anderson, A.: Toxicity to woodlice of zinc and lead-oxides added to soil litter. Ambio 14(3), 173–174 (1985)

Kramarz, P., Laskowski, R.: Effect of zinc contamination on life history parameters of a ground beetle, Poecilus cupreus. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 59(4), 525–530 (1997)

Lagisz, M., Laskowski, R.: Evidence for between-generation effects in carabids exposed to heavy metals pollution. Ecotoxicology 17(1), 59–66 (2008)

Borowska, J., Sulima, B., Niklinska, M., Pyza, E.: Heavy metal accumulation and its effects on development, survival and immuno-competent cells of the housefly Musca domestica from closed laboratory populations as model organism. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 13(12), 1402–1409 (2004)

Sheppard, D.C.: Housefly and lesser fly control utilizing the black soldier fly in manure management-systems for caged laying hens. Environ. Entomol. 12(5), 1439–1442 (1983)

NC State University: Technology report: black soldier fly (SF). In: NC State University, p. 22 (2006)

Lardé, G.: Growth of Ornidia obesa (Diptera, Syrphidae) larvae on decomposing coffee pulp. Biol. Wastes 34(1), 73–76 (1990)

Martins, E., Neves, J.A., Moretti, T.C., Godoy, W.A.C., Thyssen, P.J.: Breeding of Ornidia obesa (Diptera: Syrphidae: Eristalinae) on pig carcasses in Brazil. J. Med. Entomol. 47(4), 690–694 (2010)

Newton, G.L., Sheppard, D.C., Watson, D.W., Burtle, G., Dove, R.: Using the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens, as a value-added tool for the management of swine manure. In: Animal and Poultry Waste Management Center, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, p. 17 (2005)

Morgan, N.O., Eby, H.J.: Fly protein production from mechanically mixed animal wastes. Isr. J. Entomol. 10, 73–81 (1975)

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Velux Foundation and the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology. We are grateful to the Department of Ingeniería Agrícola of the Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica headed by Milton Solórzano, and to the Universidad EARTH (especially Edgar Alvarado). These two institutions hosted the pilot project in Costa Rica. We would also like to thank Petra Kohler and Roger Lütolf for assisting in the olfactory challenging experiments and Sylvie Peter for linguistic editing support.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Diener, S., Studt Solano, N.M., Roa Gutiérrez, F. et al. Biological Treatment of Municipal Organic Waste using Black Soldier Fly Larvae. Waste Biomass Valor 2, 357–363 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-011-9079-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-011-9079-1