Abstract

Purpose

An increasing number of thoracic decortications have been performed in Manitoba, from five in 2007 to 45 in 2014. The primary objective of this study was to define the epidemiology of decortications in Manitoba. The secondary objective was to compare patients who underwent decortication due to primary infectious vs non-infectious etiology with respect to their perioperative outcomes.

Methods

Data for this cohort study were extracted from consecutive charts of all adult patients who underwent a decortication in Manitoba from 2007-2014 inclusive.

Results

One hundred ninety-two patients underwent a decortication. The most frequent disease processes resulting in a decortication were pneumonia (60%), trauma (13%), malignancy (8%), and procedural complications (5%). The number of decortications due to complications of pneumonia rose at the greatest rate, from three cases in 2007 to 29 cases in 2014. Performing a decortication for an infectious vs a non-infectious etiology was associated with a higher rate of the composite postoperative outcome of myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury, need of vasopressors for > 12 hr, and mechanical ventilation for > 48 hr (44.4% vs 24.2%, respectively; relative risk, 1.83; 95% confidence interval, 1.1 to 2.9; P = 0.01).

Conclusion

There has been a ninefold increase in decortications over an eight-year period. Potential causes include an increase in the incidence of pneumonia, increased organism virulence, host changes, and changes in practice patterns. Patients undergoing decortication for infectious causes had an increased risk for adverse perioperative outcomes. Anesthesiologists need to be aware of the high perioperative morbidity of these patients and the potential need for postoperative admission to an intensive care unit.

Résumé

Objectif

Le nombre de décortications thoraciques réalisées au Manitoba est en constante augmentation, passant de cinq en 2007 à 45 en 2014. L’objectif principal de cette étude était de définir l’épidémiologie des décortications au Manitoba, et l’objectif secondaire de comparer les patients subissant une décortication en raison d’une étiologie primaire infectieuse vs non infectieuse en ce qui touchait à leurs pronostics périopératoires.

Méthode

Pour cette étude de cohorte, nous avons extrait les données des dossiers consécutifs de tous les patients adultes ayant subi une décortication au Manitoba entre 2007 et 2014, inclusivement.

Résultats

Cent quatre-vingt-douze patients ont subi une décortication. Les processus pathogéniques les plus fréquents motivant une décortication étaient les pneumonies (60%), les traumatismes (13%), les tumeurs malignes (8%) et les complications liées à l’intervention (5%). Le nombre de décortications dues à des complications suite à une pneumonie a affiché la plus forte augmentation, passant de trois cas en 2007 à 29 en 2014. La réalisation d’une décortication suite à une étiologie infectieuse vs non infectieuse était associée à un taux plus élevé de devenirs postopératoires combinés d’infarctus du myocarde, d’insuffisance rénale aiguë, de besoins en vasopresseurs pour > 12 h, et de ventilation mécanique pour > 48 h (44,4% vs 24,2%, respectivement; risque relatif, 1,83; intervalle de confiance 95%, 1,1 à 2,9; P = 0,01).

Conclusion

Sur une période de huit ans, les décortications se sont multipliées par neuf. Les causes potentielles sont l’augmentation de l’incidence de pneumonie, l’augmentation de la virulence des organismes, les changements d’hôte, et les changements apportés à la pratique. Les patients subissant des décortications pour des causes infectieuses courent un risque accru de devenirs périopératoires néfastes. Les anesthésiologistes doivent être conscients de l’importante morbidité périopératoire de ces patients et de la possibilité d’une admission postopératoire à l’unité de soins intensifs.

Similar content being viewed by others

A thoracic decortication is a surgical procedure that involves the removal of abnormal fibrous tissue from the pleural surfaces as well as the evacuation of fluid, pus, or debris from the pleural space to facilitate lung expansion and pleural apposition.1,2 A decortication is required when patients are symptomatic due to an unexpandable lung. This can develop from remote inflammation of the pleural space or from an active pleural process, such as a pleural infection, that fails to respond to conservative treatment. The indications for a decortication due to a malignancy depend on such factors as expected duration of survival and etiology. In general, the evidence supporting the timing and use of decortications is based on small non-randomized studies, institutional practice, and individual experience.1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 Decortications can be performed as a minimally invasive procedure by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or by open thoracotomy. The decision to perform VATS vs open decortication is an area of active research.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 A decortication is a major operation with considerable morbidity, and the mortality rate could be as high as 16% at 30 days depending on such factors as baseline comorbidities, preoperative management, and etiology.1,2,13

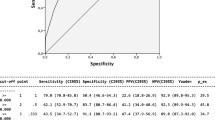

At the Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre, the main referral centre for thoracic surgery in Manitoba, there has been a progressive increase in the number of decortications, from five performed in 2007 to 45 in 2014 (Fig. 1). The primary objective of this study was to describe this patient population in terms of demographic data, comorbidities, etiology leading to the need for a decortication, course in hospital, morbidity, and mortality. These findings will serve to generate hypotheses and contribute to future investigations into the cause(s) of the large increase in the number of decortications in Manitoba. A secondary objective of this study was to compare patients who underwent decortication due to a primary infectious vs a non-infectious etiology in terms of perioperative risk, course in hospital, morbidity, and mortality.

Methods

This study was undertaken after approval was obtained from the University of Manitoba Research Ethics Board (REB) in April 2015. The REB waived the requirement for consent. Three reviewers conducted a retrospective chart review and used a data collection sheet to extract data from the charts of all adults who underwent a decortication at the Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre from January 2007 to December 2014. Ten percent of the charts were randomly selected and independently reviewed a second time to ensure data accuracy and reproducibility. From 1998-2006, three surgeons at the Health Sciences Centre as well as one surgeon at a community hospital performed thoracic surgery. There was one citywide call schedule for emergency cases, which were performed exclusively at the Health Sciences Centre. Thoracic surgery was centralized to the Health Sciences Centre in 2006, facilitating data collection.

The predictors and outcomes of interest were specified in a written protocol a priori. Collected data included patient demographics, comorbidities, preceding disease processes, antibiotic use, microbiological results, perioperative management, and course in hospital. Postoperative complications were graded according to the Ottawa Thoracic Morbidity & Mortality (TM&M) Classification System until discharge from hospital (Appendix A).21,22 Presence of a condition in the preoperative period precluded inclusion as a postoperative complication, with the exception of a condition that worsened or deviated from the normal postoperative course.

Complications were defined in the study protocol by consensus and adapted from the Ottawa TM&M Classification System based on importance and relevance to a decortication. These included myocardial ischemia or infarction, congestive heart failure, atrial arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, cerebrovascular complication, venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, acute respiratory distress syndrome, post-procedure ventilator support > 48 hr, prolonged air leak, bronchopleural fistula, prolonged pleural drainage, hemothorax, empyema, confusion/delirium, seizure, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute kidney injury, sepsis, and death during hospitalization.21,22

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Surgical Risk Calculator was used to risk stratify patients according to the severity of illness prior to undergoing surgery.23,24

The patients were divided into two groups, an infectious and a non-infectious group, based on the initial etiology that resulted in the need for a decortication. The infectious group consisted predominantly of patients who presented with a parapneumonic effusion, but it also included a small number of patients with pleural effusions secondary to another acquired or intrinsic infectious cause such as tuberculosis or an abdominal abscess. The non-infectious group consisted of patients who presented with non-infectious causes of a pleural space disorder, including trauma, malignancies, and procedural complications. The primary outcome was a composite of myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury, need for vasopressors for > 12 hr, and mechanical ventilation for > 48 hr.

The preceding disease processes and group assignments of 27 patients were independently reviewed a second time by two senior clinicians and researchers, as they had multifactorial or unclear disease processes resulting in the need for a decortication. The principal investigator resolved ties in eight cases.

Statistical analysis

To compare frequencies, we used either the Chi square or the Fisher’s exact test (if the expected cell size was < 6). We used a histogram and a Q-Q plot as well as the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests to determine whether a continuous variable was normally distributed. In the infectious group, age was the only continuous variable that was normally distributed, therefore; the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare differences in continuous data between groups. Data are represented as mean (standard deviation [SD]) for normally distributed data and median [interquartile range (IQR)] for non-normally distributed data. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Inter-rater reliability

Percent agreement and kappa were calculated for comorbidities, the etiology leading to a decortication, presence of one or more postoperative complications (any TM&M grade), presence of one or more postoperative complications resulting in an invasive procedure, intensive care unit (ICU) admission or death (> TM&M grade 2), a new postoperative ICU admission, in-hospital mortality, a positive preoperative blood culture, and a positive pleural sample. Percent agreement alone was calculated for the duration of surgery and the length of hospitalization. The median difference between reviewers was calculated for the NSQIP predicted risk of a serious complication and the NSQIP predicted risk of death at 30 days (Appendices B, C, and D).

Results

All patients

Preoperative data

There were 192 patients who underwent a decortication during the study period. One patient was excluded from analysis due to insufficient data. Three patients underwent two decortications during the same hospital admission and three patients underwent two decortications during separate hospital admissions. The second decortication was regarded as a postoperative complication or a separate procedure depending on whether it occurred during the same or a separate hospital admission, respectively.

Of the 192 patients, 146 (76%) were male and the mean (SD) age was 53 (16) yr. One hundred thirty-two (69%) patients had a smoking history, and 52 (27%) patients had a history of unhealthy alcohol use.25

The median NSQIP predicted risk of a serious postoperative complication was 20% and the median predicted risk of death was 3%. Preoperatively, 21 (11%) patients received tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, 67 (35%) patients received supplemental oxygen, and 104 (54%) patients breathed room air only.

The most frequent disease processes resulting in the need for a decortication were pneumonia (115/192, 60%), trauma (25/192, 13%), malignancy (15/192, 8%), and procedural complications (10/192, 5%) (Fig.2).

Decortications due to complications of pneumonia rose at the greatest rate (Fig. 2). Among these patients, a decortication was performed after a median [IQR] of 17 [12-27] days after symptom onset and a median of 11 [5-21] days from presentation to a healthcare provider. Once a thoracic surgeon was consulted, a decortication was performed after a median of 2 [1-4] days.

Surgical data

Decortication was carried out via a thoracotomy in 152 (79%) patients, VATS resulting in conversion to a thoracotomy in 23 (12%) patients, and VATS alone in 17 (9%) patients. The median operative duration was 101 [69-134] min.

Airway management included intubation and lung isolation with a double-lumen endotracheal tube or bronchial blocker in 131 (68%) patients. An arterial line and central line were inserted intraoperatively in 177 (92%) and 25 (13%) patients, respectively.

Postoperative data

Forty-two (22%) patients had a postoperative complication resulting in the need for an invasive procedure (e.g., endoscopy, tube thoracostomy, surgery), ICU admission, or death (TM&M grade 3 and above). The median duration of hospitalization was 15 [10-23] days. Seven (4%) patients died in hospital postoperatively.

Fifty-two (27%) patients required a postoperative ICU admission, and the median duration of intensive care was 5 [3-18] days. Twenty-three (44%) of the 52 patients requiring postoperative ICU admission were in an ICU in the immediate preoperative period.

Sixty-one (32%) patients received a packed red blood cell transfusion intraoperatively or postoperatively, and 25 (13%) patients were transfused with ≥ 3 units. Furthermore, 42 (22%) patients required postoperative vasopressors.

Pain control included patient-controlled analgesia in 131 (68%) patients, an intercostal block in 64 (33%) patients, an epidural catheter in 45 (23%) patients, and a paravertebral catheter in 34 (18%) patients. Ninety-two (48%) patients received two or more modalities for pain control.

The infectious group vs the non-infectious group

There were 126 patients in the infectious group and 66 patients in the non-infectious group. The median age was similar between groups (54.5 [46-66] yr vs 51 [36-66] yr; P = 0.14). Additionally, baseline comorbidities were similar between groups (Table 1). Based on the NSQIP score, the infectious group had a higher median predicted risk of a serious complication and death at 30 days compared with the non-infectious group (21 [16-28]% vs 16 [13-20]%; P < 0.01 and 3[1-8]% vs 2 [1-4]%, respectively; P < 0.01).

The operative duration was similar between groups (99 [69-133] min vs 103 [69-156] min; P = 0.23). Eight (6%) patients in the infectious group underwent a video-assisted thoracoscopic decortication vs 11 (17%) in the non-infectious group (P = 0.02). The decortication was right-sided in 83 (66%) cases in the infectious group and 40 (61%) cases in the non-infectious group (P = 0.47). Sixty-four (51%) patients in the infectious group had at least one postoperative complication vs 35 (53%) in the non-infectious group (P = 0.77). The rate of the composite postoperative outcome (myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury, vasopressor use > 12 hr, and mechanical ventilation > 48 hr) was higher in the infectious group than in the non-infectious group (44.4% vs 24.2%, respectively; relative risk, 1.83; 95% confidence interval, 1.1 to 2.9; P = 0.01) (Table 2). Patients in the infectious group also had a longer median duration of hospitalization than patients in the non-infectious group (15 [11-25] days vs 12 [7-21] days, respectively; P = 0.04).

The majority of patients in the infectious group (115/126, 91%) received at least one dose of an antibiotic prior to pleural sampling. The pleural sample and preoperative blood culture were positive in 74 (59%) and 13 (10%) patients, respectively. Moreover, more than one organism was isolated from the pleural space in 23 (18%) patients. Streptococcus spp., S. aureus, Gram-negative bacteria, and anaerobes represented 58/120, 7/120, 9/120, and 24/120 isolates from pleural samples, respectively. In three patients, Mycobacterium tuberculosis was the causative organism (Appendix E).

Discussion

Pleural infections are a significant problem worldwide and are an important cause for the need to perform a decortication.26,27,28 Pneumonia often precedes pleural infections; however, the pathophysiology of this process is not completely understood and the organisms isolated from pleural samples differ considerably from usual pneumonia pathogens. Administration of antibiotics prior to sampling, low diagnostic yield, and difficulty isolating and identifying fastidious organisms likely contribute to this; however, transpleural spread of bacteria may be only one of several mechanisms for developing pleural infections.28,29,30,31,32

Decortications due to parapneumonic effusions represented the largest category in this study and increased more than ninefold during the study period. The number of decortications performed due to the other etiologies remained largely unchanged (Fig. 2). Potential causes of this discrepant rise include an increase in the incidence of pneumonia, increased organism virulence, host changes, and changes in practice patterns. The number of thoracic surgeons did not change appreciably over the study period. From 2007-2012, there were three thoracic surgeons, and in 2013 and 2014 there were four thoracic surgeons on staff, but with no increase in operating room slates. With regard to the indications for decortication, the evidence supporting the timing and use of decortications is based on small non-randomized studies and institutional practice. Ultimately, it has been at the surgeon’s discretion.1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12

With regard to operative management, a thoracotomy was performed in the majority of cases. Approximately one-third of decortications were performed with a single-lumen tube and no lung isolation. This was also at the request of the surgeon, and due to the retrospective study design, it is not possible to determine why lung isolation was not requested.

More importantly, the incidence of pleural infections appears to be increasing in North America in both adults and children and for reasons that are not clear. A United States database study showed a twofold increase in the national rates of hospitalization due to parapneumonic empyema over a 13-year period.26 A Canadian study reported an approximate increase of 50% in the overall incidence of empyema from 1995–2003.27 Similarly, a more recent study by Pandian et al. reported a rising incidence of empyema in children of 3.5 to 5.6 per 100,000 from 2000–2009, again an almost 50% increase.33 Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that children and young adults may be disproportionally affected by this increase.26,27,28,33

An infectious etiology leading to a decortication was associated with almost double the rate of the composite postoperative outcome of myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury, need for vasopressors for > 12 hr, and mechanical ventilation for > 48 hr. Age, baseline comorbidities, and operative duration were similar between the infectious and non-infectious groups, but the infectious group had a higher predicted risk of a serious postoperative complication and death based on the NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator. This suggests that these patients were at significantly higher risk primarily due to the severity of their infection. Furthermore, more patients in the infectious group had new postoperative ICU admissions, suggesting a greater frequency of clinical deterioration in the intraoperative and postoperative period (Table 2). This may have been due to bacteremia from the release of a loculated infection, the associated systemic inflammatory response, as well as the physiological stress of anesthesia and decortication in an already vulnerable population.

The microbiology of pleural infections in adults is known to be complex, varies by geographic location, and can change over time. Therefore, knowledge of the organisms is important to patient care. A causative organism was identified in approximately 60% of cases in the infectious group based on pleural samples or preoperative blood cultures. Streptococcus spp. and anaerobic bacteria represented a large proportion (82/120) of isolates from the pleural space, which is consistent with other studies of community-acquired infections in adults.28,34 Community and hospital-acquired pleural infections, however, were not differentiated in this study. The isolation of bacteria consistent with oropharyngeal flora, as well as the higher frequency of right-sided surgeries, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and poor dentition in the infectious group support the contributory role of aspiration in this population.

Limitations

The retrospective design of this study limits the ability to reach conclusions as to the cause of the increase in decortications in Manitoba. With regard to the microbiology of pleural infections culminating in a decortication, it is difficult to establish the true pathogen in the majority of cases, as most patients had received antimicrobial therapy. The specific factors used to decide which patients would undergo a decortication are not known. Additionally, the number and characteristics of patients managed non-surgically are not known. It remains unclear if more patients have developed pleural space complications or if the proportion of patients managed surgically has changed over time. Furthermore, all adult patients documented as having undergone a decortication were included in this study; however, this was determined retrospectively, and due to variations in nomenclature, cases may have been missed.

Conclusion

In summary, there has been a ninefold increase in decortications performed in Manitoba over an eight-year period. Decortications are associated with considerable morbidity, mortality, and use of resources. Parapneumonic effusions were the most frequent reason for performing a decortication and increased at the greatest rate. Furthermore, a primary infectious etiology resulting in the need for a decortication was associated with a higher rate of the composite postoperative outcome (i.e., myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury, need for vasopressors for > 12 hr, and mechanical ventilation for > 48 hr) as well as a longer duration of hospitalization. There is evidence that the incidence of pleural infections due to parapneumonic effusions has been increasing in North America, which raises the question as to the extent of this problem.26,27,28 A continued increase in the need for decortications due to parapneumonic effusions and the associated perioperative complications should be anticipated. A study analyzing administrative data would be an appropriate next step to gain a further understanding of the scope and cause of this increase.

Anesthesiologists caring for patients undergoing a decortication for a parapneumonic effusion should maintain a low threshold in the preoperative period with respect to the placement of arterial and central lines due to the high rate of vasopressor use in these patients. In the postoperative period, early consultation with the intensive care unit should be considered due to the high number of patients who require postoperative mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support.

References

Rathinam S, Waller DA. Pleurectomy decortication in the treatment of the “trapped lung” in benign and malignant pleural effusions. Thorac Surg Clin 2013; 23: 51-61.

Shields TW, LoCicero J 3rd, Reed CE, Feins RH. General Thoracic Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009 .

Molnar TF. Current surgical treatment of thoracic empyema in adults. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007; 32: 422-30.

Nakas A, Martin Ucar AE, Edwards JG, Waller DA. The role of video assisted thoracoscopic pleurectomy/decortication in the therapeutic management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008; 33: 83-8.

Flores RM, Pass HI, Seshan VE, et al. Extrapleural pneumonectomy versus pleurectomy/decortication in the surgical management of malignant pleural mesothelioma: results in 663 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008; 135: 620-6, 620.e1-3.

Coote N, Kay E. Surgical versus non-surgical management of pleural empyema. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2005; 4: CD001956.

Thourani VH, Brady KM, Mansour KA, Miller JI Jr, Lee RB. Evaluation of treatment modalities for thoracic empyema: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 1998; 66: 1121-6.

Petrakis IE, Kogerakis NE, Drositis IE, Lasithiotakis KG, Bouros D, Chalkiadakis GE. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for thoracic empyema: primarily, or after fibrinolytic therapy failure? Am J Surg 2004; 187: 471-4.

Meloni G, Carretta A, Ciriaco P, et al. Decortication for chronic parapneumonic empyema: results of a prospective study. World J Surg 2004; 28: 488-93.

Mandal AK, Thadepalli H, Mandal AK, Chettipalli U. Posttraumatic empyema thoracis: 1 24-year experience at a major trauma center. J Trauma 1997; 43: 764-71.

Rzyman W, Skokowski J, Romanowicz G, Lass P, Dziadziuszko R. Decortication in chronic pleural empyema - effect on lung function. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002; 21: 502-7.

Doelken P, Sahn SA. Trapped lung. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 22: 631-6.

Tong BC, Hanna J, Toloza EM, et al. Outcomes of video-assisted thoracoscopic decortication. Ann Thorac Surg 2010; 89: 220-5.

Chambers A, Routledge T, Dunning J, Scarci M. Is video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical decortication superior to open surgery in the management of adults with primary empyema? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; 11: 171-7.

Bagheri R, Tavassoli A, Haghi SZ, et al. The role of thoracoscopic debridement in the treatment of parapneumonic empyema. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2013; 21: 443-6.

Hajjar W, Ahmed I, Al-Nassar S, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic decortication for the management of late stage pleural empyema, is it feasible? Ann Thorac Med 2016; 11: 71-8.

Ris HB, Krueger T. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and open decortication for pleural empyema. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg 2006. DOI:10.1510/mmcts.2004.000273.

Luh SP, Chou MC, Wang LS, Chen JY, Tsai TP. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in the treatment of complicated parapneumonic effusions or empyemas: outcome of 234 patients. Chest 2005; 127: 1427-32.

Wozniak CJ, Little AG. Optimal initial therapy for pleural empyema. In: Ferguson MK, editor. Difficult Decisions in Thoracic Surgery – An Evidenced-Based Approach -. 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag: London Ltd.; 2011. p. 385-93.

Chan DT, Sihoe AD, Chan S, et al. Surgical treatment for empyema thoracis: is video-assisted thoracic surgery “better” than thoracotomy? Ann Thorac Surg 2007; 84: 225-31.

Seely AJ, Ivanovic J, Threader J, et al. Systematic classification of morbidity and mortality after thoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2010; 90: 936-42.

Seely AJ, Anstee C. Ottawa TM&M. Ottawa Division of Thoracic Surgery. Available from URL: https://ottawatmm.org/ (accessed March 2017).

Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 217: 833-42.

ACS NSQIP®. Surgical Risk Calculator - Home Page. Available from URL: http://riskcalculator.facs.org/ (accessed March 2017).

Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 596-607.

Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Nuorti JP, Griffin MR. Emergence of parapneumonic empyema in the USA. Thorax 2011; 66: 663-8.

Finley C, Clifton J, Fitzgerald JM, Yee J. Empyema: an increasing concern in Canada. Can Respir J 2008; 15: 85-9.

Corcoran JP, Wrightson JM, Belcher E, Decamp MM, Feller-Kopman D, Rahman NM. Pleural infection: past, present, and future directions. Lancet Respir Med 2015; 3: 563-77.

Smith DT. Experimental aspiratory abscess. Arch Surg 1927; 14: 231-9.

Wrightson JM, Wray JA, Street TL, Chapman SJ, Crook DW, Rahman NM. S114 previously unrecognised oral anaerobes in pleural infection. Thorax 2014; 69(Suppl 2).

Bassis CM, Erb-Downward JR, Dickson RP, et al. Analysis of the upper respiratory tract microbiotas as the source of the lung and gastric microbiotas in healthy individuals. MBio 2015; 6: e00037.

Huxley EJ, Viroslav J, Gray WR, Pierce AK. Pharyngeal aspiration in normal adults and patients with depressed consciousness. Am J Med 1978; 64: 564-8.

Pandian TK, Aho JM, Ubl DS, Moir CR, Ishitani MB, Habermann EB. The rising incidence of pediatric empyema with fistula. Pediatr Surg Int 2016; 32: 215-20.

Maskell NA, Batt S, Hedley EL, Davies CW, Gillespie SH, Davies RJ. The bacteriology of pleural infection by genetic and standard methods and its mortality significance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 817-23.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Gregory L. Bryson, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author contributions

Jay Gorman, Duane Funk, Sadeesh Srinathan, John Embil, Linda Girling, and Stephen Kowalski helped conduct the study, analyze the data, and write the manuscript. Jay Gorman, Linda Girling, and Stephen Kowalski helped collect the data. Duane Funk, Sadeesh Srinathan, John Embil, Linda Girling, and Stephen Kowalski helped design the study. Duane Funk is the author responsible for archiving the study files.

Funding

University of Manitoba Department of Anesthesiology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This report describes human research. IRB contact information: Bannatyne Research Ethics Board P126 Pathology Building, 770 Bannatyne Avenue, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, R3E 0W3. Phone: 204 789-3255 Fax: 204 789-3414.

Appendices

Appendix A

Ottawa thoracic morbidity & mortality (TM&M) grading system

Grade | Description |

|---|---|

1 | Any complication without need for pharmacologic treatment or other intervention |

2 | Any complication that requires pharmacologic treatment or minor intervention only |

3 | (a) Any complication that requires surgical, radiological, endoscopic intervention, or multi-therapy. The intervention does not require general anesthesia (b) Any complication that requires surgical, radiological, endoscopic intervention, or multi-therapy. The intervention requires general anesthesia |

4 | (a) Any complication requiring ICU management and life support. Single organ dysfunction (b) Any complication requiring ICU management and life support. Multi-organ dysfunction |

5 | Any complication leading to the death of the patient |

Appendix B

Percent agreement and kappa for categorical data

Categorical Data | Percent Agreement | Kappa |

|---|---|---|

Ischemic heart disease | 100% | N/A |

Cerebrovascular disease | 100% | N/A |

Peripheral artery disease | 100% | N/A |

Hypertension | 90% | 0.79 |

Atrial arrhythmia | 100% | N/A |

Chronic pulmonary disease | 100% | N/A |

Obstructive sleep apnea | 100% | N/A |

Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 100% | N/A |

Liver cirrhosis | 95% | 0.64 |

Chronic kidney disease | 95% | 0.00 |

End-stage renal disease | 100% | N/A |

Obesity | 100% | N/A |

Smoking history | 90% | 0.78 |

Substance use | 90% | 0.80 |

Poor dentition | 85% | 0.00 |

Diabetes mellitus | 100% | N/A |

Etiology leading to a decortication | 90% | 0.81 |

Presence of 1 or more postoperative complications (any TM&M grade) | 90% | 0.80 |

Presence of 1 or more postoperative complications resulting in an invasive procedure, ICU admission or death (> TM&M grade 2) | 85% | 0.63 |

New postoperative ICU admission | 100% | N/A |

In-hospital mortality | 100% | N/A |

Positive preoperative blood culture | 100% | N/A |

Positive pleural sample | 95% | 0.89 |

Appendix C

Percent agreement for ratio data

Ratio Data | Percent Agreement |

|---|---|

Duration of decortication (min) | 90% |

Length of hospitalization (days) | 100% |

Appendix D

Difference between reviewers for the NSQIP surgical risk calculator results

NSQIP Results | Median Difference Between Reviewers | IQR |

|---|---|---|

NSQIP predicted risk of a serious complication (%) | 4.5% | 1.75-10.25 |

NSQIP predicted risk of death (%) | 1% | 0-2 |

Appendix E

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gorman, J., Funk, D., Srinathan, S. et al. Perioperative implications of thoracic decortications: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 64, 845–853 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-017-0896-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-017-0896-y