Abstract

Purpose

Application of ultrasound in regional anesthesia has now become the standard of care and its use has shown to reduce complications. Nevertheless, gaining expertise in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia requires the acquisition of new cognitive and technical skills. In addition, due to a reduction in resident working hours and enforcement of labour laws and directives across various states and countries, trainees perform and witness fewer procedures. Together, these issues create challenges in the teaching and learning of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia in the time-based model of learning.

Principal findings

The challenges of teaching ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia are similar to those experienced by our surgical counterparts with the advent of minimally invasive surgery. In order to overcome these challenges, our surgical colleagues used theories of surgical skills training, simulation, and the concept of deliberate practice and feedback to shift the paradigm of learning from experience-based to competency-based learning.

Conclusion

In this narrative review, we describe the theory behind the evolution of surgical skills training. We also outline how we can apply these learning theories and simulation models to a competency-based curriculum for training in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia.

Résumé

Objectif

L’application de l’échoguidage en anesthésie régionale constitue désormais la norme de soins. En outre, il a été démontré que son utilisation réduisait les complications. Toutefois, l’acquisition d’une expertise en anesthésie régionale par échoguidage nécessite l’acquisition de nouvelles compétences à la fois cognitives et techniques. De plus, en raison de la réduction des heures de travail des résidents et de l’application des lois et des directives du travail dans divers états et pays, les stagiaires réalisent et observent moins d’interventions. Ensemble, ces facteurs ajoutent des défis à l’enseignement et à l’apprentissage de l’anesthésie régionale par échoguidage dans notre modèle d’apprentissage fondé sur le temps.

Constatations principales

Les défis de l’enseignement de l’anesthésie régionale par échoguidage sont semblables à ceux qu’ont eu à relever nos confrères en chirurgie à l’avènement de la chirurgie minimalement invasive. Afin de les surmonter, nos collègues chirurgiens se sont servis de théories sur la formation des compétences chirurgicales, la simulation, et le concept d’une pratique délibérée et de rétroactions afin de modifier le paradigme de l’apprentissage d’un apprentissage fondé sur l’expérience à un apprentissage fondé sur la compétence.

Conclusion

Dans ce compte rendu narratif, nous exposons la théorie sous-jacente à l’évolution de la formation en compétences chirurgicales. Nous décrivons également la façon dont nous pouvons appliquer ces théories d’apprentissage et ces modèles de simulation à un programme de cours fondé sur les compétences pour la formation en anesthésie régionale par échoguidage.

Similar content being viewed by others

The application of ultrasound for regional anesthesia is emerging as a standard of care, and its use in experienced hands is known to reduce complications and improve the overall quality of the procedure.1 Gaining expertise in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia (UGRA) requires acquisition of new knowledge and technical skills, including, but not limited to, sonoanatomy, hand-eye coordination, and skills in ultrasound scanning and needle insertion. The advent of UGRA in anesthesia is similar to the advent of laparoscopic surgery in general surgery. The new knowledge and skill required for laparoscopic surgery resulted in an evolution of training involving theories in the acquisition of motor skills, simulation training, and a well-defined competency-based curriculum.2,3

In this review, we describe how to apply the theory behind surgical skills training to advance UGRA teaching in the future and reshape the curriculum for UGRA training.

An evolution in the training of surgical skills

In 1889, William S. Halsted4,5 proposed the original concept of the volume-based training model for surgical training, which involved trainees learning under the direct supervision of experienced and senior surgeons. For more than 100 years, junior surgeons have been trained by this method, which has become costly, time-consuming, and variable in effectiveness.6 The drawback of this method of training is its dependence/reliance on the sheer amount of exposure and not on a specifically designed curriculum.7

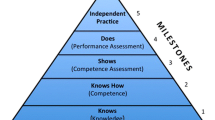

In a seminal article by Grantcharov and Reznick, the authors stated that “see one, do one, is not the best way to teach complex technical procedures needed in many hospital-based specialties”.7 They highlight the need for a specifically designed curriculum where each skill has defined stages and outcomes and where each stage must be successfully completed in succession. Different learning theories and models have been incorporated to reshape the curriculum, e.g., the theory of motor skills acquisition by Fitts and Posner,8 validated models of teaching psychomotor skills in the clinical setting (Table 1),9,10 as well as the deliberate practice model described by Ericsson.11

These developments in the learning theories of surgical education parallel broader changes in the philosophy of medical education. This shift in training began in the United Kingdom with the launch of Tomorrow’s Doctors in 1993,3,12 followed by “The CanMEDS initiative…”,13 “The Scottish doctor…”,14 and “The ACGME outcome project…” by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education,15 and resulted in many similar programs in other countries around the world.16,17 Canadian physician educators are most familiar with the CanMEDS framework that has been adopted by 16 countries around the world.18 The CanMEDS competencies consist of seven physician roles: Medical Expert, Communicator, Collaborator, Health Advocate, Scholar, Leader, and Professional.19 This program focuses on outcomes rather than on the pathways and processes required to attain these outcomes.20 The seven physician roles are characterized as qualities that physicians require to meet the healthcare needs of their patients, communities, and society.18 Within this framework, educators can begin to teach with the outcome in mind.

Based on these theories and models, a number of components have been incorporated into current surgical skills training: 1) highly structured activities created specifically to improve performance in certain domains through immediate feedback, e.g., simulation training that focuses on developing specific aspects of a skill set; 2) emphasis on ongoing assessment and evaluation (feedback); 3) de-emphasis on the length of exposure to procedure or experience; and 4) breakdown of a procedure into smaller less complex tasks with definite end goals.

Grantcharov and Reznick’s theory-based learning model includes two phases.7 The first phase is initiating novice training outside the clinical setting. Students acquire cognitive knowledge, indications, and possible complications of the procedure as well as operative knowledge of the equipment. Trainees can gain this expertise outside the clinical setting by reviewing a video of the procedure with its key steps. Trainees can then clearly explain and demonstrate each step of the procedure. For instance, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedure is broken down into the following key steps: 1) access and insertion of a port; 2) exposure and dissection of Calot’s triangle; 3) clipping and cutting the cystic artery and the cystic duct; and 4) dissecting and extracting the gallbladder. After acquiring the basic skills, trainees can then practice the procedure in a simulation setting. Importantly, feedback and evaluations are recognized as critical elements of this method of training. A number of studies have confirmed the effectiveness of simulation.21,22

The second phase starts once the trainees have gained competence in their basic skills in simulated practice. When junior surgeons perform the surgery during this phase, they are allowed to execute only one step of the procedure on each occasion. Once they have mastered all steps, they can progress to performing the complete procedure under supervision. Each step of this training is accompanied by an assessment and feedback, which has shown to contribute to faster skills acquisition and to reduce learning curves in the operating theatre.23 This method of surgical skills training emphasizes achievement of competency at each successive level of training prior to progressing to the next level.

Skills training in regional anesthesia

In 1980, Bridenbaugh observed that regional anesthesia training varied substantially among residency training programs.24 To provide some uniformity in training, the Anesthesiology Residency Review Committee (RRC) of the ACGME formally defined the minimum requirement for training in regional anesthesia in 1996.25 This experience-based or time-based training required completion of 50 epidural blocks, 50 spinal blocks, and 40 peripheral nerve blocks. A follow-up survey (following the establishment of a minimal number of blocks by the RRC) indicated that residents fulfilled the minimum requirement for spinal and epidural blocks in the United States and Europe26,27 but failed to perform a sufficient number of peripheral nerve blocks. Data obtained from annual training reports submitted to the Anesthesiology RRC in 2000 revealed that approximately 40% of all residents had inadequate experience in peripheral nerve blockade.28 These findings confirm that, if all types of nerve blocks are taught during a time-based residency training, trainees may experience limited practice for each block and are unlikely to attain expertise in any particular block at the end of their training.

The advent of the use of ultrasound in regional anesthesia introduced a new set of knowledge and skills, including knowledge of sonoanatomy, and the skills of ultrasound scanning, needle insertion, needle tracking, and needle tip visualization.29 Ultrasound presents new challenges in teaching and learning similar to those presented by laparoscopic surgery. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia requires the acquisition of new knowledge and a new set of motor skills (i.e., transformation of a three-dimensional structure into a two-dimensional image) and a requirement for eye-hand coordination in the manipulation of instruments (e.g., block needle in the case of UGRA).

Training in UGRA: time for change in the curriculum

The same forces that reshaped surgical skills training now force anesthesia educators to re-examine how we teach the skills essential for regional anesthesia. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) and the European Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Therapy (ESRA) have published joint committee guidelines for training in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia.29 The ASRA-ESRA guidelines suggest that the curriculum for UGRA training should include knowledge delivery, simulation training with feedback, and clinical training. We propose that this method of training should be implemented gradually through successive phases of the procedure until competency is achieved to perform the entire procedure under supervision. In addition, to implement this training model, it is imperative to design a curriculum based on specific learning objectives.

Pre-training regional anesthesia novices (Table 2)

Knowledge

The order of teaching knowledge and skills for UGRA training may vary from that of surgical skills training. Smith et al.30 describe the qualities of an expert in regional anesthesia as a practitioner with technical competence as well as the non-technical skills of handling the patient and knowing the limits of safe practice. In order to emphasize the skills other than technique, we recommend that regional anesthesia trainees acquire knowledge about the specific blocks, including the relevant anatomy, indications, and complications, prior to learning the basic practical skills. This knowledge base should also include the pre-procedure workup and post-procedure management of the patient. Trainees can gain this knowledge outside the operating room through didactic lectures or e-modules. The content in each component can be assessed with pretests and posttests to ascertain that trainees have acquired the requisite knowledge. Though this teaching method improves knowledge, it may not improve hands-on ultrasound skills.31 For this reason, we propose that trainees progress to skills acquisition once they have acquired the knowledge base.

Skills

Initial teaching of basic skills (i.e., the relevant sonoanatomy scanning skills and needle insertion skills) should be performed within a controlled environment that provides the trainee with a low stress learning experience. Simulation laboratories provide such optimal conditions where trainees can practice sonoanatomy scanning skills on live models and enhance their needle insertion skills on simulation models. In addition, they can learn the basic skills common for all blocks, including ultrasound transducer positioning, ultrasound transducer orientation, as well as needle insertion, needle tracking, and needle tip visualization skills. Simulation models available for UGRA offer human body contours that facilitate effective teaching of ultrasound scanning techniques. Targets are available within these models, providing a useful tool for novice trainees to practice their needling techniques.

In order for the trainees to improve their performance, expert feedback is required as they perform each task.32 The importance of feedback has been clearly shown in previous studies. de Oliveira Filho et al. examined two skills required for UGRA on a bovine phantom: the ability to insert a needle parallel to an ultrasound beam and the ability to insert a needle until it touches a target tendon.33 With no feedback provided to the trainees, the authors predicted that the students would require 37 and 109 attempts, respectively, to reach 95% proficiency in each skill. In contrast, Sites et al.34 showed that ultrasound novices improved both accuracy and speed in reaching a target on a turkey breast phantom when they were provided feedback after every attempt. The students in the latter study attained proficiency much earlier than those in the former study. de Oliveira Filho and Sites33,34 have shown that teaching on low-fidelity simulation models with feedback vs without feedback produces mixed results. This may indicate that simulation teaching alone without feedback may be less beneficial than simulation teaching combined with feedback.

There is supporting evidence that simulation training can enhance knowledge acquisition and performance. Three studies have tested teaching UGRA with simulation vs an equivalent control group without simulation; all three studies enrolled anesthesiology trainees.35-37 Niazi et al.35 studied two groups of anesthesiology residents who received training on needling and proper hand-eye coordination using ultrasound to perform blocks on real patients. Their study results showed that the group with one hour of simulation training achieved more success than the control group with no simulation training. Looking at different durations of simulation training, Baranauskas et al. 6 showed that two hours of simulation training in needling allowed students to perform faster and with fewer mistakes than those who received one hour of training. Similarly, those with one hour of simulation training performed better than those with no simulation training. Results of a study by Udani et al. 37 on placement of subarachnoid blocks showed that students with simulation training had improved performance scores (as per a checklist) when compared with students with no simulation training.

In addition to bench simulation models, virtual reality simulation has also been shown to improve knowledge and techniques prior to clinical exposure. In a study evaluating a virtual reality lumbar spine model for ultrasound pre-puncture scanning of the spine, anesthesia trainees with full access to the interactive model were compared with anesthesia trainees with only partial access to the non-interactive anatomy component of the model. Both groups were provided access for two weeks. When the trainees were evaluated on a real simulated patient within a week of training, those with full access were able to identify a median of 11.5/12 key structures on an ultrasound pre-puncture scan of the lumbar spine, whereas those with only partial access scored a median of 5.5/12.38

Another important component of simulation training is the evaluation of the trainees. The evaluation is necessary to confirm if the trainees adequately achieved their goals and also to determine their preparedness to apply their skills in a clinical setting. Tools are required for this robust assessment, but unfortunately, not many assessment tools are available for UGRA. Cheung et al. have developed a checklist and global rating scale (GRS) specifically for all UGRA procedures.39 This GRS could differentiate novices from experienced anesthesiologists when it was used for both on-site and remote summative assessments on a patient and simulation model. In contrast, the checklist could not discern the two groups on a simulation model remotely and differentiation was marginally significant with on-site scoring.40 A 47-item multiple choice online test comprising both knowledge and skills assessments has recently been developed.41 This test is important because it represents an objective assessment of the respondent’s level of training in UGRA and it can differentiate between junior and senior regional anesthesiologists.

Clinical training in UGRA

Trainees should first gain skill in basic peripheral nerve blocks where the nerves lie superficially and are easily identifiable. Also, in order to minimize complications, it is best to begin on patients who do not have challenging anatomy (e.g., obesity).29 In our view, the initial phase of training should include ultrasound scanning so trainees can gain an understanding of image interpretation. This phase should include the ability to identify various anatomical structures, such as nerves, blood vessels, muscles, and fascial planes. The next phase of clinical training should incorporate needle insertion, and the last phase should be injection of local anesthesia. Each phase can be taught separately, and progression to the next phase should occur only once the trainee has mastered the preceding phase. During performance, the trainee should be able to describe each step of the procedure. Once the trainees achieve competency in all phases, they can then be allowed to perform the entire procedure in the clinical setting under supervision.

Conclusion

The changing learning environment and the new knowledge and skills required for UGRA have rendered the apprenticeship model ineffective. To incorporate the new changes, there should be a shift in the learning paradigm to a competency-based program. This shift has already occurred in many other disciplines, and to keep up with the times, it is important to develop a teaching curriculum for UGRA where trainees are assessed by their competence in performing UGRA rather than by the number of procedures performed. In this article, we have provided a rough roadmap on how to develop such a curriculum as well as on the key components of the program. Further study on evaluation tools and objective assessment is required.

References

Walker KJ, McGrattan K, Aas-Eng K, Smith AF. Ultrasound guidance for peripheral nerve blockade. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD006459.

DesCoteaux JG, Leclere H. Learning surgical technical skills. Can J Surg 1995; 38: 33-8.

Aggarwal R, Moorthy K, Darzi A. Laparoscopic skills training and assessment. Br J Surg 2004; 91: 1549-58.

Osborne MP. William Stewart Halsted: his life and contributions to surgery. Lancet Oncol 2007; 3: 256-65.

Carter BN. The fruition of Halsted’s concept of surgical training. Surgery 1952; 3: 518-27.

Haluck RS, Krummel TM. Computers and virtual reality for surgical education in the 21st century. Arch Surg 2000; 135: 786-92.

Grantcharov TP, Reznick RK. Teaching procedural skills. BMJ 2008; 336: 1129-31.

Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott M. Motor learning and recovery of function. In: Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott M, editors. Motor Control: Translating Research into Clinical Practice. Maryland: Wolters Kluwer; 2007. p. 32-3.

George JH, Doto FX. A simple five-step method for teaching technical skills. Fam Med 2001; 33: 577-8.

Walker M, Peyton JW. Teaching in theatre. In: Teaching and Learning in Medical Practice. Rickmansworth: Manticore Europe; 1998: 171-80.

Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Acad Med 2004; 79: S70-81.

General Medical Council [UK]. Tomorrow’s Doctors. London: GMC 2009. Available from URL: http://www.gmcuk.org/Tomorrow_s_Doctors_1214.pdf_48905759.pdf (accessed March 2016).

Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach 2007; 29: 642-7.

Simpson JG, Furnace J, Crosby J, et al. The Scottish doctor-learning outcomes for the medical undergraduate in Scotland: a foundation for competent and reflective practitioners. Med Teach 2002; 24: 136-43.

Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach 2007; 29: 648-54.

Graham IS, Gleason AJ, Keogh GW, et al. Australian curriculum framework for junior doctors. Med J Aust 2007; 186(7 Suppl): S14-9.

Laan RF, Leunissen RR, van Herwaarden CL. The 2009 framework for undergraduate medical education in the Netherlands. GMS Z Med Ausbild 2010; 27: Doc35.

Norman G. CanMEDS and other outcomes. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2011; 16: 547-51.

Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. Available from URL: http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/framework/canmeds_full_framework_e.pdf (accessed March 2016).

Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach 2007; 29: 642-7.

Larsen CR, Soerensen JL, Grantcharov TP, et al. Effect of virtual reality training on laparoscopic surgery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009; 338: b1802.

Kulcsar Z, O’Mahony E, Lovquist E, et al. Preliminary evaluation of a virtual reality-based simulator for learning spinal anesthesia. J Clin Anesth 2013; 25: 98-105.

Grantcharov TP, Schulze S, Kristiansen VB. The impact of objective assessment and constructive feedback on improvement of laparoscopic performance in the operating room. Surg Endosc 2007; 21: 2240-3.

Bridenbaugh LD. Are anesthesia resident programs failing regional anesthesia? Reg Anesth 1982; 7: 26-8.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program requirements for graduate medical education in anesthesiology. Available from URL: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/1996-97.pdf (accessed March 2016).

Kopacz DJ, Neal JM, Pollock JE. The regional anesthesia “learning curve”. What is the minimum number of epidural and spinal blocks to reach consistency? Reg Anesth 1996; 21: 182-90.

Bouaziz HMF, Narchi P, Poupard M, Auroy Y, Benhamou D. Survey of regional anesthetic practice among French residents at time of certification. Reg Anesth 1996; 22: 218-22.

Kopacz DJ, Neal JM. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine: residency training-the year 2000. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2002; 27: 9-14.

Sites BD, Chan VW, Neal JM, et al. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine and the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy joint committee recommendations for education and training in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2010; 35: S74-80.

Smith AF, Pope C, Goodwin D, Mort M. What defines expertise in regional anaesthesia? An observational analysis of practice. Br J Anaesth 2006; 97: 401-7.

Woodworth GE, Chen EM, Horn JL, Aziz MF. Efficacy of computer-based video and simulation in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia training. J Clin Anesth 2014; 26: 212-21.

Black P, Wiliam D. Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 2009; 21: 5-31.

de Oliveira Filho GR. Helayel PE, da Conceicao DB, Garzel IS, Pavei P, Ceccon MS. Learning curves and mathematical models for interventional ultrasound basic skills. Anesth Analg 2008; 106: 568-73.

Sites BD, Gallagher JD, Cravero J, Lundberg J, Blike G. The learning curve associated with a simulated ultrasound-guided interventional task by inexperienced anesthesia residents. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2004; 29: 544-8.

Niazi AU, Haldipur N, Prasad AG, Chan VW. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia performance in the early learning period: effect of simulation training. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012; 37: 51-4.

Baranauskas MB, Margarido CB, Panossian C, Silva ED, Campanella MA, Kimachi PP. Simulation of ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve block: learning curve of CET-SMA/HSL anesthesiology residents (Portuguese). Rev Bras Anestesiol 2008; 58: 106-11.

Udani AD, Macario A, Nandagopal K, Tanaka MA, Tanaka PP. Simulation-based mastery learning with deliberate practice improves clinical performance in spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2014; 2014: 659160.

Niazi AU, Tait G, Carvalho JC, Chan VW. The use of an online three-dimensional model improves performance in ultrasound scanning of the spine: a randomized trial. Can J Anesth 2013; 60: 458-64.

Cheung JJ, Chen EW, Darani R, McCartney CJL, Dubrowski A, Awad IT. The creation of an objective assessment tool for ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia using the Delphi method. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012; 37: 329-33.

Burckett-St Laurent DA, Niazi AU, Cunningham MS, et al. A valid and reliable assessment tool for remote simulation-based ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2014; 39: 496-501.

Woodworth GE, Carney PA, Cohen JM, et al. Development and validation of an assessment of regional anesthesia ultrasound interpretation skills. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2015; 40: 306-14.

Funding

This project was funded by internal departmental funding.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Vincent Chan receives equipment support for research from BK Medical and consultation fees from Philips Medical Systems and Smiths Medical. The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare. Dr. Philip Peng received equipment support from Sonosite Fujifilm Canada.

Author Contributions

Ahtsham U. Niazi, Philip W. Peng, Melissa W. Ho, and Akhilesh Tiwari made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the article. Ahtsham U. Niazi, Philip W. Peng, and Vincent W. Chan were responsible for drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Melissa W. Ho and Akhilesh Tiwari made substantial contributions to drafting the article and to the illustrations.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Gregory L. Bryson, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Niazi, A.U., Peng, P.W., Ho, M. et al. The future of regional anesthesia education: lessons learned from the surgical specialty. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 63, 966–972 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-016-0653-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-016-0653-7