Abstract

Purpose

Clonidine may help prevent cardiac complications in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery and receiving chronic beta-blocker therapy. We conducted a multicentre pilot randomized trial to estimate recruitment rates for a full-scale trial and to assess the safety and tolerability of combining clonidine with chronic beta-blockade.

Methods

Patients who were at elevated perioperative cardiac risk, receiving chronic beta-blockade, and scheduled for major non-cardiac surgery were recruited in a blinded (participants, clinicians, outcome assessors) placebo-controlled randomized trial at three Canadian hospitals. Participants were randomized to clonidine (0.2 mg oral tablet one hour before surgery, plus 0.2 mg·day−1 transdermal patch placed one hour before surgery and removed four days after surgery or hospital discharge, whichever came first) or matching placebo. Feasibility was evaluated based on recruitment rates, with each centre being required to recruit 50 participants within 12-18 months. Additionally, we reviewed study drug withdrawals and safety outcomes, including clinically significant hypotension or bradycardia.

Results

Eighty-two of the 168 participants were randomized to receive clonidine and 86 to receive placebo. The average time to recruit 50 participants at each centre was 14.3 months. Six patients (7%) withdrew from clonidine, while four (5%) withdrew from placebo. Based on qualitative review, there were no major safety concerns related to clonidine. There was a moderate overall rate of cardiac morbidity, with 18 participants (11%) suffering postoperative myocardial infarction.

Conclusion

This pilot randomized trial confirmed the feasibility, safety, and tolerability of a full-scale trial of oral and transdermal clonidine for reducing the risk of cardiac complications during non-cardiac surgery. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00335582.

Résumé

Objectif

La clonidine pourrait contribuer à prévenir les complications cardiaques chez des patients subissant une chirurgie non cardiaque et recevant un traitement chronique par bêta-bloqueurs. Nous avons dirigé une étude pilote randomisée, multicentrique, pour estimer les vitesses de recrutement d’une étude définitive et pour évaluer l’innocuité et la tolérabilité d’une association de la clonidine avec des bêta-bloqueurs administrés en traitement chronique.

Méthodes

Des patients qui présentaient un risque cardiaque périopératoire élevé, recevaient un traitement chronique par bêta-bloqueurs et devaient subir une intervention chirurgicale majeure non cardiaque programmée ont été recrutés dans une étude randomisée en insu (participants, cliniciens, évaluateurs de l’aboutissement), contrôlée par placebo, dans trois hôpitaux canadiens. Les participants ont été randomisés pour recevoir de la clonidine (un comprimé de 0,2 mg per os une heure avant l’opération et 0,2 mg·jour−1 en timbre épidermique placé une heure avant l’opération et retiré quatre jours plus tard ou au moment du congé de l’hôpital, selon ce qui survenait en premier) ou un placebo correspondant. La faisabilité a été évaluée en fonction des vitesses de recrutement, chaque centre devant recruter 50 participants dans un délai de 12 à 18 mois. De plus, nous avons analysé les arrêts prématurés du traitement étudié et les résultats d’innocuité, y compris les épisodes cliniquement significatifs d’hypotension ou de bradycardie.

Résultats

Quatre-vingt-deux des 168 participants ont été randomisés dans le groupe recevant la clonidine et 86 dans le groupe recevant le placebo. Le délai moyen de recrutement des 50 participants dans chaque centre a été de 14,3 mois. Six patients (7 %) ont été retirés du groupe clonidine et quatre patients (5 %) ont été retirés du groupe placebo. Sur le plan qualitatif, l’analyse n’a relevé aucun problème majeur d’innocuité lié à la clonidine. Il y a eu un taux global modéré de morbidité cardiaque, 18 participants (11 %) souffrant d’infarctus du myocarde postopératoire.

Conclusion

Cette étude pilote randomisée a confirmé la faisabilité, l’innocuité et la tolérabilité d’une étude à grande échelle de l’administration orale et transdermique de la clonidine sur la réduction du risque de complications cardiaques au cours d’une chirurgie non cardiaque. Cette étude a été enregistrée sur le site www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00335582.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cardiac complications are an important concern for patients undergoing major non-cardiac surgery. Significant myocardial injury occurs after 8% of such procedures1 and leads to increased short- and long-term mortality.1,2 While beta-blockers showed initial promise for preventing these complications,3 these benefits may be offset by increased risks of hypotension, stroke, and death.4

Beta-blockers likely prevent myocardial infarction (MI) through an attenuation of perioperative hypertension and tachycardia, which in turns helps preserve the balance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand. Clonidine is an alternative drug that may act along similar mechanisms. Clonidine and other alpha-2 adrenergic agonists inhibit central sympathetic outflow and thereby attenuate perioperative hemodynamic abnormalities.5-8 In previous systematic reviews,9,10 we found that alpha-2 adrenergic agonists may help prevent perioperative mortality and MI. Clonidine also has other benefits, including analgesia and anxiolysis without associated respiratory depression.11 Furthermore, it has a favourable pharmacokinetic profile. It is available in a transdermal preparation that can be administered easily to post-surgical patients who are unable to consume oral medications.12

Definitive evidence that clonidine prevents major cardiac complications after non-cardiac surgery will entail a large randomized controlled trial (RCT) with sufficient statistical power to detect plausible moderate-sized treatment effects. When assessing the feasibility of such a trial, it is important to consider whether clonidine can be administered in combination with chronic beta-blocker therapy. Approximately 20-40% of patients undergoing major non-cardiac surgery receive chronic beta-blocker therapy.13,14 Such individuals may stand to benefit from clonidine since they remain at elevated perioperative cardiac risk.13 We therefore conducted the Evaluating Perioperative Ischemia reduction with Clonidine (EPIC) study, a multicentre pilot RCT of clonidine in patients who were at intermediate- to high-risk of cardiac complications, receiving chronic beta-blockade, and scheduled to undergo major non-cardiac surgery. Our objectives were to estimate recruitment rates for a full-scale RCT and to assess the safety and tolerability of combining clonidine with chronic beta-blockade. Recruitment would be considered successful if each participating centre recruited 50 participants within 12-18 months.

Methods

Sample

Potential participants were recruited in the preoperative assessment clinics of the Toronto General Hospital (Toronto, ON, Canada), Vancouver General Hospital (Vancouver, BC, Canada), and Victoria Hospital (London, ON, Canada). Eligibility criteria for participants included age 45 yr or older, considered at intermediate- to high-risk of cardiac complications, scheduled to undergo elective non-cardiac surgery with an expected postoperative hospital length of stay of at least 48 hr for medical reasons, and receiving oral beta-blocker therapy for at least 30 days before surgery. Patients were deemed at intermediate- to high-risk of cardiac complications if they were undergoing major vascular surgery, intermediate-risk surgery (i.e., intraperitoneal, intrathoracic, carotid endarterectomy, major orthopedic, radical prostatectomy, or head-and-neck procedures)15 with at least one risk factor, or other surgery with at least two clinical risk factors. The risk factors of interest were coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral arterial disease, age 70 yr or older, and estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤ 60 mL·min−1.16 Exclusion criteria were pre-existing use of alpha-2 agonists, prior adverse reaction to alpha-2 agonists, decompensated heart failure, known left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 40%, systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg, known clinically significant aortic stenosis, and concomitant life-threatening disease likely to limit life expectancy to ≤ 30 days. Patients, clinicians, data collectors, and outcome adjudicators were blinded to treatment assignment. This trial was approved by Health Canada as well as the Research Ethics Boards of the University Health Network (May 2005), London Health Sciences Centre (December 2006), and University of British Columbia (January 2007). All participants provided informed consent.

Randomization

The research pharmacy at Toronto General Hospital prepared a computer-generated randomization schedule employing permuted blocks of varying size with stratification by hospital. Site-specific randomization lists were forwarded to the research pharmacies at the participating hospitals. To ensure concealment of treatment allocation, randomization lists were available only to the research pharmacists. On the morning of surgery, a research pharmacist prepared the study drugs according to the randomization list and sent the study drugs to the preoperative holding area.

Interventions

Participants in the intervention arm received clonidine as a 0.2 mg oral tablet (Apo-Clonidine®, Apotex Inc., Weston, ON, Canada) and a transdermal patch (Catapres-TTS-2®, Boehringer Ingelheim Inc., Ridgefield, CT, USA) one hour before surgery. These patches, which provided a continuous delivery of 0.2 mg·day−1, were removed on postoperative day four or hospital discharge (whichever occurred earlier). Participants in the placebo arm received matching oral placebo tablets and inert patches. The protocol was adapted from previous regimens that reduced plasma catecholamine levels and myocardial ischemia in surgical patients without causing adverse hemodynamic effects.5,12 It also ensured that participants received clonidine during the 72-hr postoperative period during which perioperative MI generally occurs.17

Perioperative management

Participants received their usual dose of oral beta-blocker on the morning of surgery and resumed their normal regimen as soon as they could consume tablets orally. Participants temporarily unable to swallow tablets instead received beta-blockers via a nasogastric tube. Participants were also permitted to receive supplemental intravenous metoprolol at the discretion of their physicians. Other aspects of clinical care were left to the discretion of the participants’ physicians, aside from a restriction on using open-label clonidine.

Data collection and outcomes

At the time of recruitment, we documented information on age, sex, height, weight, blood pressure, heart rate, comorbidities, medications, and serum creatinine concentration. Perioperative cardiac risk was estimated using the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI).18 Following surgery, information was collected on surgical procedure, anesthetic type, postoperative heart rate, and postoperative blood pressure. We measured heart rate and blood pressure every 15 min in the postanesthetic care unit (PACU) and then every eight hours until postoperative day three or hospital discharge (whichever occurred earlier). If several measurements were taken within an eight-hour interval, the lowest heart rate and blood pressure values were recorded.

Electrocardiograms (ECG) and troponin assays were performed in the PACU at eight hours after surgery and then once daily until the third postoperative day or until hospital discharge (whichever occurred earlier). The participating centres used standard (i.e., not high-sensitivity) troponin I (Toronto General Hospital, Vancouver General Hospital) or troponin T (Victoria Hospital) assays. We captured the following clinical outcomes: mortality, MI, myocardial injury (troponin concentration exceeding the threshold at which the coefficient of variation for the assay was 10%), non-fatal cardiac arrest, heart failure, and acute stroke. Participant follow-up occurred daily while in hospital and then by phone call at 30 days after surgery. Myocardial infarction was defined as myocardial injury in combination with clinical symptoms of ischemia, typical ECG changes, coronary artery intervention, or presumed new changes on echocardiography or radionuclide imaging.19 Two reviewers blinded to treatment group adjudicated all diagnoses of MI. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or a third blinded reviewer. Safety outcomes included premature discontinuation of the study drug, clinically significant hypotension (postoperative systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg requiring a vasopressor or inotropic agent, study drug discontinuation, or intra-aortic balloon pump), and clinically significant bradycardia (postoperative bradycardia requiring a pacemaker, sympathomimetic agent, atropine, or study drug discontinuation). Decisions to discontinue the study drug to address perceived complications of clonidine (e.g., hypotension) that were not responsive to usual interventions (e.g., adjustment of epidural infusion) were left at the discretion of individual responsible physicians.

Sample size and criteria for assessing feasibility

To have sufficient statistical power for detecting a plausible reduction in postoperative cardiac events, a full-scale RCT of perioperative clonidine will require a large sample size. For example, if the rate of non-fatal MI or death in the control arm is assumed to be 6%,20 7,204 participants are required to detect a 25% relative risk reduction (two-sided alpha of 0.05, 80% power, and continuity correction).

The purpose of this pilot study was to assess the feasibility of conducting such a large multicentre trial in intermediate-to high-risk surgical patients receiving chronic beta-blocker therapy. Our primary objective was to determine whether each centre could quickly reach a recruitment rate of approximately four participants per month and sustain the rate for 12 months. Based on this objective, the planned sample size was 55 participants at each site (i.e., 165 participants for the entire study). We considered feasibility to be demonstrated if each centre could recruit 50 participants within 12-18 months after an initial run-in period to recruit the first five participants at each site. If these 50 participants could be recruited within 12 months, we estimated that a larger multicentre trial with recruitment of three years’ duration would involve approximately 48 participating centres of similar size. If 18 months were required instead, 73 participating centres would have to be involved. Previous experience with the POISE-1 trial indicated that this degree of collaboration was feasible.20 We anticipated that the number of required centres could be further reduced if a future multicentre trial also included patients not receiving chronic beta-blockade. In addition to assessing recruitment rates, we qualitatively reviewed safety outcomes and study drug withdrawals related to the clonidine regimen.

Analyses

All analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis using Stata version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and the R statistical language.Footnote 1 We reported continuous data as means with standard deviations or with interquartile ranges if the data were skewed. Categorical data were reported as absolute numbers and percentages. Since this feasibility study did not have statistical power to detect clinically meaningful differences, we did not statistically test for differences between groups.21 Instead, we estimated between-group differences and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for those differences. Multivariable linear regression modelling was used to calculate the average difference over time (with associated 95% CI) in systolic blood pressure measurements following PACU discharge, while adjusting for any differences in baseline preoperative blood pressure. The model used generalized estimating equations to account for correlation of repeated measurements within individual participants. Similar methods were used to calculate average differences in heart rate measurements following PACU discharge.

Results

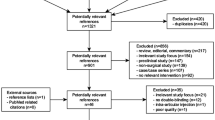

There were 168 participants randomized to clonidine (n = 82) or placebo (n = 86). One patient in each group did not undergo surgery (Fig. 1). Due to incremental availability of funding, recruitment at the Toronto General Hospital (June 2006 to November 2007), Vancouver General Hospital (January 2008 to August 2009), and Victoria Hospital (September 2007 to November 2008) occurred in overlapping time periods with different start dates.

The preoperative characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Overall, 71% of participants had RCRI scores of one or two, while 17% had scores of three or greater. There were some moderately large imbalances between treatment arms, as would be expected in a relatively small RCT.22

Recruitment of patients to this pilot RCT proved to be feasible. Following the recruitment of the first five participants at each site, the average time to recruit the subsequent 50 participants was 14.3 months. The times required at the three sites were 11.6, 12.8, and 18.5 months. Trends in cumulative recruitment are presented in Fig. 4 (available as Electronic Supplemental Material). The clonidine protocol used in this study was reasonably tolerated, with six patients (7%) needing to be withdrawn from clonidine therapy and four (5%) withdrawn in the placebo arm. The postoperative hemodynamic status of the study arms is presented in Table 2. Episodes of postoperative systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg were common, occurring in 25% (n = 42) of all participants and 24% (n = 21) of individuals in the control arm. Despite all participants receiving chronic beta-blockade, episodes of postoperative tachycardia were also frequent, with 40% (n = 67) of all participants having episodes of heart rate > 90 beats·min−1. Following PACU discharge, the mean heart rate (Fig. 2) in the clonidine arm was 0.4 beats·min−1 lower (95% CI, 4.8 lower to 3.9 higher). During this same period, the mean systolic blood pressure in the clonidine arm (Fig. 3) was 5.8 mmHg lower (95% CI, 11.0 lower to 0.7 lower).

Trends in postoperative heart rate over time in the clonidine and placebo arms. Heart rate was measured at the time of study recruitment (i.e., baseline measurement in the preoperative assessment clinic) and over the first 72 hr after surgery. Each participant’s heart rate was measured at least every eight hours postoperatively (i.e., three measurements per day as denoted on the x-axis). The lowest measured values within each interval are presented in this figure. Boxplots are used to represent the distribution of heart rate at each time point. The box extends from the 25th to 75th percentile, while the thick horizontal line within each box represents the median value. The whisker bars denote the minimum and maximum values

Trends in postoperative systolic blood pressure over time in the clonidine and placebo arms. Blood pressure was measured at the time of study recruitment (i.e., baseline measurement in the preoperative assessment clinic) and over the first 72 hr after surgery. Each participant’s blood pressures was measured at least every eight hours postoperatively (i.e., three measurements per day as denoted on the x-axis). The lowest measured values within each interval are presented in this figure. Boxplots are used to represent the distribution of blood pressure at each time point. The box extends from the 25th to 75th percentile, while the thick horizontal line within each box represents the median value. The whisker bars denote the minimum and maximum values

Rates of postoperative events in the study arms are presented in Table 3. Within the overall sample, 11% (n = 18) of participants suffered postoperative MI and 16% (n = 27) suffered myocardial injury. By comparison, the overall risk of 30-day mortality was 1% (n = 2).

Discussion

This pilot RCT at three large Canadian hospitals supported the feasibility of a full-scale trial of perioperative clonidine, for several reasons.

First, the overall recruitment rate of intermediate- to high-risk patients receiving chronic beta-blockade met the study threshold for determining feasibility, with each centre recruiting slightly fewer than four participants per month. While one centre did exceed the maximum 18-month recruitment period by two weeks, this short delay was due to unforeseen circumstances necessitating a temporary halt to recruitment as opposed to inadequate recruitment rates while the study was active. These findings therefore support the feasibility of successfully completing a full-scale trial of perioperative clonidine within a reasonable time period. Second, the results support the safety and tolerability of our perioperative clonidine regimen. Based on qualitative feedback from research personnel, the regimen was simple to administer, monitor, and follow up. The rate of active study drug discontinuation was 7%, which is lower than rates observed in RCTs of perioperative beta-blockade such as the POISE-1 and DIPOM trials.20,23 In addition, there were no early suggestions of safety concerns related to the clonidine regimen. For example, rates of significant hypotension in the clonidine and placebo arms were qualitatively similar to rates observed in the placebo arm of the POISE-1 trial.20 Third, the study inclusion criteria successfully identified patients at intermediate- to high-risk of perioperative cardiac complications. Approximately 11% of patients suffered perioperative MI, which is higher than rates observed in the POISE-1 trial.20 Overall, the observed rates of participant recruitment and outcome events, in combination with initial suggestions of safety and tolerability, point to the feasibility of employing our proposed perioperative regimen of oral and transdermal clonidine in a full-scale definitive RCT.

Aside from confirming the feasibility of a full-scale RCT of perioperative clonidine, several other aspects of our results merit discussion. First, despite all patients receiving beta-blockade and the presence of protocols to continue these drugs in the perioperative period, inadequate control of heart rate occurred frequently, with almost 40% of participants experiencing a heart rate > 90 beats·min−1. This observation points to the difficulties with achieving adequate control of heart rate with beta-blockade. Notably, previous RCTs of perioperative beta-blockade have also observed a persistently high heart rate in participants receiving active treatment. For example, in the DIPOM trial, the heart rate among participants randomized to receive metoprolol ranged from 40-120 beats·min−1 on the first day after surgery.23 Second, perioperative hypotension also occurred frequently, with more than 25% of all participants experiencing a systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg during their hospitalization. Notably, only half of these cases were clinically significant, in that the episode of hypotension necessitated pharmacologic intervention or withdrawal of the study drug. Nonetheless, this observation points to the frequency of perioperative hypotension during usual clinical practice at tertiary-care Canadian medical centres. Third, this study was not designed to facilitate formal statistical comparison between the rates of adverse events in the study arms. Stated otherwise, the sample size provides insufficient statistical power to make these comparisons.

Fourth, this feasibility study should now be interpreted in light of the POISE-2 trial, which was published during the peer review process for our present paper.24 The POISE-2 trial assessed clonidine and acetylsalicylic acid in a factorial fashion for preventing perioperative cardiac complications in 10,010 intermediate- to high-risk patients.24 It found that a clonidine regimen very similar to that used in the EPIC trial did not prevent 30-day mortality (risk difference 0.02%; 95% CI, −0.4 to 0.5) or MI (risk difference 0.7%; 95% CI, −0.3 to 1.6) but significantly increased rates of significant hypotension (risk difference 10.5%; 95% CI, 8.6 to 12.5). There was no evidence of subgroup effects in the 2,359 (24%) participants concurrently using beta-blockers. Our feasibility study was largely concordant with this full-scale multicentre trial. The successful completion of the POISE-2 trial within 30 months without early termination for major safety concerns supports our conclusions regarding feasible recruitment rates and safety of the proposed clonidine regimen. Additionally, the confidence limits for differences in rates of clinical events (Table 3) overlap with the estimates from the POISE-2 trial. While our original intent was to proceed to a full-scale RCT of perioperative clonidine if the EPIC trial showed feasibility, the negative results of the POISE-2 trial (in which several EPIC trial investigators participated) now indicates that a separate full-scale trial, while feasible, is likely not needed. Stated otherwise, there now exists strong evidence that clonidine does not prevent perioperative cardiovascular complications.

Conclusions

This multicentre pilot RCT confirmed the feasibility, safety, and tolerability of a full-scale trial of perioperative oral and transdermal clonidine for reducing perioperative cardiac risk during major non-cardiac surgery. Consistent with this interpretation, the large POISE-2 trial used a very similar perioperative regimen and successfully completed recruitment, albeit in both users and non-users of chronic beta-blockade. While the present study has shown feasibility of a full-scale trial of perioperative clonidine, the negative results of the POISE-2 trial indicate that such a separate full-scale RCT, while feasible, is likely not needed.

Notes

The R Project for Statistical Computing. R. A language and environment for statistical computing. (Available from URL: http://www.R-project.org). Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013 (accessed July 2014).

References

The Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators. Association between postoperative troponin levels and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2012; 307: 2295-304.

Levy M, Heels-Ansdell D, Hiralal R, et al. Prognostic value of troponin and creatine kinase muscle and brain isoenzyme measurement after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2011; 114: 796-806.

Mangano DT, Layug EL, Wallace A, Tateo I. Effect of atenolol on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 1713-20.

Bangalore S, Wetterslev J, Pranesh S, Sawhney S, Gluud C, Messerli FH. Perioperative beta blockers in patients having non-cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2008; 372: 1962-76.

Ellis JE, Drijvers G, Pedlow S, et al. Premedication with oral and transdermal clonidine provides safe and efficacious postoperative sympatholysis. Anesth Analg 1994; 79: 1133-40.

McSPI-Europe Research Group. Perioperative sympatholysis. Beneficial effects of the alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist mivazerol on hemodynamic stability and myocardial ischemia. Anesthesiology 1997; 86: 346-63.

Muzi M, Goff DR, Kampine JP, Roerig DL, Ebert TJ. Clonidine reduces sympathetic activity but maintains baroreflex responses in normotensive humans. Anesthesiology 1992; 77: 864-71.

Talke P, Li J, Jain U, et al. Effects of perioperative dexmedetomidine infusion in patients undergoing vascular surgery. Anesthesiology 1995; 82: 620-33.

Wijeysundera DN, Naik JS, Beattie WS. Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists to prevent perioperative cardiovascular complications: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2003; 114: 742-52.

Wijeysundera DN, Bender JS, Beattie WS. Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists for the prevention of cardiac complications among patients undergoing surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD004126.

Pawlik MT, Hansen E, Waldhauser D, Selig C, Kuehnel TS. Clonidine premedication in patients with sleep apnea syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg 2005; 101: 1374-80.

Wallace AW, Galindez D, Salahieh A, et al. Effect of clonidine on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2004; 101: 284-93.

London MJ, Hur K, Schwartz GG, Henderson WG. Association of perioperative beta-blockade with mortality and cardiovascular morbidity following major noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2013; 309: 1704-13.

Wijeysundera DN, Mamdani M, Laupacis A, et al. Clinical evidence, practice guidelines, and beta-blocker utilization before major noncardiac surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012; 5: 558-65.

Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACCF/AHA Focused Update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2009; 120: e169-276.

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976; 16: 31-41.

Devereaux PJ, Xavier D, Pogue J, et al. Characteristics and short-term prognosis of perioperative myocardial infarction in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154: 523-8.

Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100: 1043-9.

Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined - a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36: 959-69.

POISE Study Group. Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (POISE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 371: 1839-47.

Choi PT, Beattie WS, Bryson GL, Paul JE, Yang H. Effects of neuraxial blockade may be difficult to study using large randomized controlled trials: The PeriOperative Epidural Trial (POET) Pilot Study. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e4644.

Chu R, Walter SD, Guyatt G, et al. Assessment and implication of prognostic imbalance in randomized controlled trials with a binary outcome – a simulation study. PloS One 2012; 7: e36677.

Juul AB, Wetterslev J, Gluud C, et al. Effect of perioperative beta blockade in patients with diabetes undergoing major non-cardiac surgery: randomised placebo controlled, blinded multicentre trial. BMJ 2006; 332: 1482.

Devereaux PJ, Sessler DJ, Leslie K, et al. POISE-2 Investigators. Clonidine in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 1504-13.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the research personnel at the participating hospitals for their outstanding performance in patient recruitment, participant follow-up, and data collection. Also, we gratefully acknowledge the physicians, nurses, and other health care staff who cared for the study patients.

Financial support

Dr. Wijeysundera is supported in part by a Clinician-Scientist Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Drs. Wijeysundera and Beattie are supported in part by Merit Awards from the Department of Anesthesia at the University of Toronto. Dr. Beattie is the Fraser Elliot Chair of Cardiac Anesthesia at the University Health Network. This study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (Grant-in-Aid NA 6087) and the Canadian Anesthesia Research Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author Contributions

Duminda Wijeysundera, Peter Choi, Neal Badner, Penelope Brasher, Diego Delgado, and W. Scott Beattie contributed to the conception and design of the study. Duminda Wijeysundera, Peter Choi, Neal Badner, George Dresser, and W. Scott Beattie contributed to the conduct of the study. Duminda Wijeysundera, Penelope Brasher, and W. Scott Beattie contributed to the analysis of the data, and all authors contributed to its interpretation. Duminda Wijeysundera drafted the manuscript, and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. Duminda Wijeysundera, Peter Choi, and Neal Badner are responsible for archiving the study files.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12630_2014_226_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Fig. 4 Trends in the cumulative number of study participants at each study site. These trends are presented for the period following the recruitment of the first five participants at each site. The initial period required for recruiting the first five participants was deemed a training period to allow each site to optimize their recruitment procedures.(PDF 189 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wijeysundera, D.N., Choi, P.T., Badner, N.H. et al. A randomized feasibility trial of clonidine to reduce perioperative cardiac risk in patients on chronic beta-blockade: the EPIC study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 61, 995–1003 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-014-0226-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-014-0226-6