Abstract

Purpose

Correct placement of the endotracheal tube (ETT) occurs when the distal tip is in mid-trachea. This study compares two techniques used to place the ETT at the correct depth during intubation: tracheal palpation vs placement at a fixed depth at the patient’s teeth.

Methods

With approval of the Research Ethics Board, we recruited American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I-II patients scheduled for elective surgery with tracheal intubation. Clinicians performing the tracheal intubations were asked to “advance the tube slowly once the tip is through the cords”. An investigator palpated the patient’s trachea with three fingers spread over the trachea from the larynx to the sternal notch. When the ETT tip was felt in the sternal notch, the ETT was immobilized and its position was determined by fibreoptic bronchoscopy. The position of the ETT tip was compared with our hospital standard, which is a depth at the incisors or gums of 23 cm for men and 21 cm for women. The primary outcome was the incidence of correct placement. Correct placement of the ETT was defined as a tip > 2.5 cm from the carina and > 3.5 cm below the vocal cords.

Results

Movement of the ETT tip was readily palpable in 77 of 92 patients studied, and bronchoscopy was performed in 85 patients. Placement by tracheal palpation resulted in more correct placements (71 [77%]; 95% confidence interval [CI] 74 to 81) than hospital standard depth at the incisors or gums (57 [61%]; 95% CI 58 to 66) (P = 0.037). The mean (SD) placement of the ETT tip in palpable subjects was 4.1 (1.7) cm above the carina, 1.9 cm (1.5-2.3 cm) below the ideal mid-tracheal position.

Conclusion

Tracheal palpation requires no special equipment, takes only a few seconds to perform, and may improve ETT placement at the correct depth. Further studies are warranted.

Résumé

Objectif

On définit le bon positionnement de la sonde endotrachéale (SET) lorsque l’extrémité distale de la SET se situe à mi-trachée. Cette étude compare deux techniques pour placer la SET à la bonne profondeur pendant l’intubation: la palpation trachéale et le positionnement à une profondeur fixe par rapport aux dents du patient.

Méthode

Après avoir obtenu le consentement du Comité d’éthique de la recherche, nous avons recruté des patients de statut physique I-II selon la classification de l’American Society of Anesthesiologists devant subir une chirurgie non urgente avec intubation trachéale. On a demandé aux cliniciens réalisant les intubations trachéales « d’avancer la sonde lentement une fois que l’extrémité a dépassé les cordes vocales ». Un chercheur a palpé la trachée du patient à l’aide de trois doigts étendus sur la trachée du larynx à l’échancrure sternale. Une fois l’extrémité de la SET sentie dans l’échancrure sternale, la SET a été immobilisée et sa position a été déterminée par bronchoscopie par fibres optiques. La position de l’extrémité de la SET a été comparée à notre norme hospitalière, soit une profondeur aux incisives ou aux gencives de 23 cm chez les hommes et de 21 cm chez les femmes. Le critère d’évaluation principal était l’incidence de bon positionnement. Un bon positionnement de la SET était défini si l’extrémité était située à > 2,5 cm de la carène et > 3,5 cm sous les cordes vocales.

Résultats

Le mouvement de l’extrémité de la SET était facile à palper chez 77 des 92 patients à l’étude, et la bronchoscopie a été réalisée chez 85 patients. Le positionnement par palpation trachéale a entraîné davantage de bons positionnements (71 [77 %]; intervalle de confiance [IC] 95 % 74 à 81) par rapport à la profondeur standardisée dans notre hôpital par rapport aux incisives ou aux gencives (57 [61 %]; IC 95 % 58 à 66) (P = 0,037). Le positionnement moyen (ET) de l’extrémité de la SET chez les patients palpables était situé à 4,1 (1,7) cm au-dessus de la carène, 1,9 cm (1,5-2,3 cm) sous la position idéale à mi-trachée.

Conclusion

La palpation trachéale ne nécessite aucun matériel spécial, ne prend que quelques secondes, et pourrait améliorer le positionnement de la SET à la bonne profondeur. Des études supplémentaires sont nécessaires.

Similar content being viewed by others

Ideal placement of the endotracheal tube (ETT) is achieved when the tip is in mid-trachea with the patient’s head in neutral alignment. Unrecognized misplacement of the ETT is an uncommon but significant cause of hypoxemia and death during general anesthesia and critical care.1,2 Malpositioning can be too shallow and result in inadvertent extubation, too deep and result in endobronchial placement with hypoxia or barotrauma, or esophageal and lead to hypoxemia and inflation of the stomach.3-6 Malpositioning is common, occurring in 14-61% of patients.4,7-9

Using a finger to palpate the ETT tip in the sternal notch has been described in infants and has resulted in a correct placement rate of 93%.10,11 Confirmation of correct ETT placement is currently performed by several methods, and currently, x-ray and bronchoscopy are the gold standards.12,13 Simple measurement of the length of the ETT at the incisors or, for edentulous patients at the upper gums, (21 cm for women and 23 cm for men) is widely used and simple but may not be reliable. This measurement method (MM) is commonly used in our hospitals.4 The MM can be improved by using additional anatomical landmarks to determine ETT tube length and can result in a reduction in the incidence of excessively deep placement from 58.8-24%.9

Safe placement is assumed when the ETT tip remains in the trachea in spite of neck flexion or extension. Once fixed to the patient’s face, the ETT tip moves downward toward the carina by a mean (SD) of 1.3 (0.6) cm with neck flexion and upward by 1.7 (0.8) cm with neck extension.14 If we choose limits that equal the mean plus two standard deviations, i.e., 2.5 and 3.5 cm, respectively, safe placement could be achieved in 95% of patients. Thus, we considered that the ETT was correctly placed when the distance from the tip to the carina was > 2.5 cm and the distance from the tip to the vocal cords was > 3.5 cm. This study aimed to assess the practicality and accuracy of a technique to assess ETT depth by palpating the anterior neck to feel the moving tip of the ETT reach the sternal notch. We hypothesized that tracheal palpation (TP) of the ETT tip while it is moving down the trachea would enable correct placement in adults (more than 2.5 cm above the carina and more than 3.5 cm below the vocal cords) more often than placing the ETT at a fixed distance from the incisors/gums (MM).

Methods

Study design

We employed a cross-sectional observational study design to explore routine tracheal intubation of patients in the operating room. The anesthesiologist slowly advanced the ETT while the investigator palpated the patient’s larynx and upper trachea and determined ETT placement with bronchoscopic measurements.

Subjects

Following University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board approval (2011/08/10), written informed consent was obtained from a convenience sample of adult patients. Patients included in the study were 18 yr of age and older and scheduled for elective surgery with endotracheal intubation between November 2011 and May 2012 in the acute care teaching hospitals of Saskatoon. Due to a lack of previous published studies regarding TP, we chose a sample size of 100 patients. Patients who were physiologically unstable, those who needed emergency surgery, and those without endotracheal intubation were excluded.

Equipment

The attending anesthesiologist performed or supervised the intubation and chose the drugs, intubation technique, patient positioning, and ETT. A stylet was used at the anesthesiologist’s discretion. The depth of insertion of the ETT was measured with a flexible bronchoscope (Olympus® LF2, Olympus America, Center Valley, PA, USA).

Experimental intervention

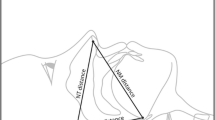

The clinicians performing the intubation were instructed to “advance the ETT slowly once the tip is through the cords” while an investigator palpated the patient’s trachea with three fingers (i.e., index, middle, and ring finger) of one hand as follows: one over the cricothyroid membrane, one in the sternal notch, and one over the anterior trachea midway between. When the ETT tip was felt in the sternal notch, the anesthesiologist was asked to stop advancing the tube. The investigator then immobilized the ETT and measured the depth of the ETT at the upper incisors (upper gums for edentulous patients). If the ETT movement was not palpable, ETT depth was set by and at the discretion of the anesthesiologist.

Measurements

Patient demographics (age, sex, height, weight) were recorded. The investigator who performed the palpations stated the ease/certainty of palpating the ETT tip as “strongly felt”, “moderately easily felt”, “barely felt”, or “not felt”.

The depth of the ETT was measured by bronchoscopy. With the ETT firmly held to avoid any change in depth, a fibreoptic bronchoscope was advanced to the carina and the depth at the elbow connector was marked with a spring clip. The bronchoscope was then withdrawn to the ETT tip and a second clip was placed. The bronchoscope was withdrawn further until the light from the bronchoscope tip shone through the cricothyroid membrane, and then a third clip was placed on the bronchoscope. The distance between the first two clips was equal to the distance from the carina to the ETT tip, and the measurement of the gap between the second and third clips was equal to the distance from the ETT tip to the cricothyroid membrane. Adding a standard value for the distance from the cricothyroid membrane to the vocal cords gave the distance from the ETT tip to the vocal cords. This mean (SD) value was taken from teaching-file magnetic resonance images of ten adult females [1.056 (0.11) cm] and ten adult males [1.17 (0.12) cm] with normal upper airway anatomy.

After using TP to place the ETT, the marking of the ETT depth at the patient’s teeth was recorded. The difference between that marking and the standard depth of 21 cm for women and 23 cm for men was calculated to obtain a calculated estimate of the distance from ETT tip to carina and ETT tip to vocal cords that would have been measured if the ETT had been positioned according to the MM method. The number of patients with incorrect placement with the TP method was compared with the number of patients with incorrect placement estimated by the MM method.

The measurements allowed a calculation of the length of the trachea from the carina to the vocal cords. The depth of mid-trachea was obtained from this calculation, and the distance between the ETT tip and mid-trachea was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Demographics and ease of ETT palpation were tabulated. “Strongly felt” and “moderately easily felt” were combined as a single “palpable” category, while “barely felt” or “not felt” were combined as “impalpable” for analysis. Frequency of ETT placement by TP was reported by categories: “too shallow” (tip < 3.5 cm from vocal cords) or “too deep” (tip < 2.5 cm above carina); correct placement lay between these extremes. P values < 0.05 were considered as indicating significant difference. Chi square analysis was used to compare categorical data, and two-sided Student’s t tests were used to compare rational data. Linear regression was used to compare subjects’ height with the distance from the subjects’ teeth to carina. Statistical calculations were performed with SigmaPlot™ version 11.0 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

The technique was explored in the first nine subjects, when it became clear that the investigator should feel the ETT tip as it passed each palpating finger in turn. Following this, the remaining 92 subjects were analyzed by intent-to-treat analysis using the conservative assumption for missing data points that all placements not measured as correct placement by TP would be assumed to be misplaced for TP, and all calculated values for MM that were not incorrect would be assumed to be correct placements for MM.

Results

One hundred four patients were approached; two patients chose not to participate in the study, and 102 patients participated (Table 1). The first nine patients were removed from analysis because they were assessed prior to development of the definitive technique (feeling the ETT with each palpating finger as it moved down the trachea). There was one esophageal intubation, which was detected by the investigators before it was detected by the anesthesiologist. The anesthesiologist was not comfortable to continue with the study protocol during re-intubation, leaving 92 subjects. In seven cases, the bronchoscope was not available when needed, and thus, bronchoscopy was performed in 85 of the 92 analyzed subjects. Demographic data are presented in Table 2.

Distance to carina

In the 85 subjects who underwent bronchoscopy, height correlated weakly with the distance from teeth/gums to carina with the following regression formula (R 2 = 0.28; P < 0.001):

Ease of palpation

Movement of the ETT tip was “strongly felt” in 60 subjects, “moderately easily” felt in 17 subjects, “barely felt” in seven subjects, and “not felt” in nine subjects. One of the “not felt” subjects was the individual who had an esophageal intubation. The subject was removed from the study at the request of the anesthesiologist. We grouped the first two categories (palpable = 77; 84%) and the last two categories (impalpable = 15; 16%) for analysis. Numbers were too small to analyze factors that led to palpation difficulties.

Intubation technique

Disposable plastic cuffed ETTs (Mallinckrodt® Hi-Lo, Mallinckrodt, Juarez, Mexico), 7-mm internal diameter for women and 8-mm internal diameter for men, were used for all intubations. All but one intubation was done with direct laryngoscopy using a curved #3 Macintosh blade. The exception was intubation with a GlideScope® video laryngoscope Movement of the ETT tip was not palpable in this case.

ETT position

Table 3 and Figs. 1 and 2 show placement results using tracheal palpation (TP) vs using the measurement method (MM). Using intent-to-treat analysis, placement by TP resulted in more correct placements than MM positioning (P = 0.037). The bronchoscope was not available for all subjects; however, for the subjects who underwent bronchoscopy, the mean (SD) depth of the ETT tip from the upper incisors (or upper gums) was 21.5 (1.7) cm in males and 19.5 (4.3) cm in females. For the same subjects, the ETT was too deep in 12 using TP and in 34 using MM, and the ETT was too shallow in one subject using TP. Therefore, measurement was inaccurate in 13 (15%) subjects using TP and in 34 (40%) subjects using MM. There were no endobronchial intubations (95% CI 0 to 3; 0% to 4.2%).15 Calculated MM placement would have resulted in five endobronchial intubations (95% CI 4.3 to 8.6); P = 0.04 compared with TP. The ETT tip in palpable subjects was 4.1(1.7) cm above the carina, which was 1.9 cm (95% CI 1.5 to 2.3 cm) below the ideal of mid-trachea.

Discussion

ETT placement

Seventy-seven percent of ETTs were correctly placed using TP in the patients where the ETT tip was palpable (Table 2). This result was significantly better than MM with 61% of ETTs correctly placed. Tracheal palpation was applicable in only 77(84%) of 92 intubations; however, 15% of these resulted in incorrect ETT depth compared with as many as 40% with MM, which may have prevented all endobronchial intubations. Tracheal palpation resulted in placing the ETT tip below the midpoint of the trachea. If the TP technique were modified to include the instruction to pull back one centimetre after the ETT tip is felt in the sternal notch, it would have resulted in only two situations where the ETT was too deep. It is known that intubation with direct laryngoscopy extends the cervical spine, moving the trachea upward out of the thorax.16 With this movement, the sternal notch then becomes too deep a target if the ETT is fixed prior to placing the patient’s head in the neutral position.

Ease of palpation

During initial explorations in the first nine subjects, we improved the technique. Several misplacements occurred before we realized the importance of feeling the movement of the ETT tip with each finger in turn as opposed to simply feeling movement. This is likely because the ETT sometimes catches on the anterior larynx and causes a sudden movement of the entire larynx and upper trachea, which is felt with three fingers at once. We initially misinterpreted this as either the ETT tip was already at the sternal notch when it had only begun its descent down the trachea or the ETT tip was “difficult to palpate”. The results presented here were obtained only after the improved technique was employed.

Other techniques

Ballottement of the ETT cuff in the trachea was examined in three studies for controlling ETT depth.17-19 The technique involves compressing and releasing the inflated cuff over the trachea while feeling and watching the corresponding movement of the pilot balloon. In one of these studies, cuff ballottement resulted in proper positioning of the ETT in all 120 intensive care unit patients assessed.18 The other two studies found 20% and 18% of intubations with a distal tip lying 2.5 cm or less from the carina.17,19 We found a correlation between height and the distance from patients’ teeth/gums to the carina. Numbers were not sufficient to analyze data by sex. It is possible that a height-related rule could be derived that would be more accurate than MM.

Endobronchial intubation

With TP, we had no endobronchial intubations, and this was significantly different from MM, which, if applied, would have produced five endobronchial intubations.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A strength of this study is that it was conducted using patients in the usual clinical situation. Nevertheless, the study was conducted on stable patients having elective surgery under the controlled conditions of the operating room. Similar results may not apply to emergency intubation on the ward or in the field. The study was observational, not a randomized controlled trial.

The study would have been stronger if all subjects had undergone bronchoscopy.

Another weakness is that estimating the position of the vocal cords from the point when the bronchoscope light shines most brightly through the cricothyroid membrane is not a validated measurement technique. In addition, the exact point of maximum illumination is somewhat subjective. This measurement, however, applies only to cases where intubation is too shallow. Another weakness is that palpation was performed by investigators, whereas in the clinical situation, it would be performed by those who assist with intubation. The MM involved a calculation, not a direct measurement, but the validity of the calculation is very plausible since changing the ETT depth at the teeth would be expected to result in a quantitatively similar change in position of the ETT tip in the trachea.

Clinical utility

Tracheal palpation of the ETT – while the ETT is advanced slowly until its tip is felt in the sternal notch and then pulled back one centimetre – can decrease the risk of ETT misplacement. The technique takes no special equipment and can be performed in less than five seconds. It does not exclude other techniques used to confirm ETT location. Combining techniques may further decrease ETT misplacement. In order to be clinically useful, those who stand beside the patient’s head and assist with tracheal intubation (e.g., nurses, anesthesia assistants, and emergency medical technicians) must show that the palpation technique can be mastered. We have planned or have begun the following further studies: the ease or difficulty of teaching and learning the technique, TP in children, TP in adults with ultrasound instead of palpation, and a study to determine whether TP can detect esophageal intubation. Other refinements of the technique may result from these studies.

References

Caplan RA, Posner KL, Ward RJ, Cheney FW. Adverse respiratory events in anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 1990; 72: 828-33.

Schwartz DE, Matthay MA, Cohen NH. Death and other complications of emergency airway management in critically ill adults. A prospective investigation of 297 tracheal intubations. Anesthesiology 1995; 82: 367-76.

Harris EA, Arheart KL, Penning DH. Endotracheal tube malposition within the pediatric population: a common event despite clinical evidence of correct placement. Can J Anesth 2008; 55: 685-90.

Owen RL, Cheney FW. Endobronchial intubation: a preventable complication. Anesthesiology 1987; 67: 255-7.

Mackenzie M, MacLeod K. Repeated inadvertent endobronchial intubation during laparoscopy. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91: 297-8.

Clyburn P, Rosen M. Accidental oesophageal intubation. Br J Anaesth 1994; 73: 55-63.

Brunel W, Coleman DL, Schwartz DE, Peper E, Cohen NH. Assessment of routine chest roentgenograms and the physical examination to confirm endotracheal tube position. Chest 1989; 96: 1043-5.

Geisser W, Maybauer DM, Wolff H, Pfenninger E, Maybauer MO. Radiological validation of tracheal tube insertion depth in out-of-hospital and in-hospital emergency patients. Anaesthesia 2009; 64: 973-7.

Evron S, Weisenberg M, Harow E, et al. Proper insertion depth of endotracheal tubes in adults by topographic landmarks measurements. J Clin Anesth 2007; 19: 15-9.

Bednarek FJ, Kuhns LR. Endotracheal tube placement in infants determined by suprasternal palpation: a new technique. Pediatrics 1975; 56: 224-9.

Jain A, Finer NN, Hilton S, Rich W. A randomized trial of suprasternal palpation to determine endotracheal tube position in neonates. Resuscitation 2004; 60: 297-302.

Gray P, Sullivan G, Ostryzniuk P, McEwen TA, Rigby M, Roberts DE. Value of postprocedural chest radiographs in the adult intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1992; 20: 1513-8.

Rudraraju P, Eisen LA. Confirmation of endotracheal tube position: a narrative review. J Intensive Care Med 2009; 24: 283-92.

Kim JT, Kim HJ, Ahn W, et al. Head rotation, flexion, and extension alter endotracheal tube position in adults and children. Can J Anesth 2009; 56: 751-6.

Newman TB. If almost nothing goes wrong, is almost everything all right? Interpreting small numerators. JAMA 1995; 274: 1013.

Sawin PD, Todd MM, Traynelis VC, et al. Cervical spine motion with direct laryngoscopy and orotracheal intubation. An in vivo cinefluoroscopic study of subjects without cervical abnormality. Anesthesiology 1996; 85: 26-36.

Ledrick D, Plewa M, Casey K, Taylor J, Buderer N. Evaluation of manual cuff palpation to confirm proper endotracheal tube depth. Prehosp Disaster Med 2008; 23: 270-4.

Pattnaik SK, Bodra R. Ballotability of cuff to confirm the correct intratracheal position of the endotracheal tube in the intensive care unit. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2000; 17: 587-90.

Pollard RJ, Lobato EB. Endotracheal tube location verified reliably by cuff palpation. Anesth Analg 1995; 81: 135-8.

This study was funded by the Department of Anesthesia, University of Saskatchewan. No author has any commercial or other affiliation that is, or may be perceived to be, a conflict of interest.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McKay, W.P., Klonarakis, J., Pelivanov, V. et al. Tracheal palpation to assess endotracheal tube depth: an exploratory study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 61, 229–234 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-013-0079-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-013-0079-4