Abstract

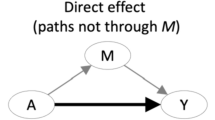

Mediation analysis evaluates the significance of an intermediate variable on the causal pathway between an exposure and an outcome. One commonly utilized test for mediation involves evaluation of counterfactual effects, estimated from separate regression models, corresponding to a composite null hypothesis. However, the “compositeness” of this null hypothesis is not commonly acknowledged and accounted for in mediation analyses. We describe a generalized multivariate approach in which these separate regression models are fit simultaneously in a single parsimonious model. This multivariate modeling approach can reproduce standard mediation analysis and has notable advantages over separate regression models, including the ability to combine distributions in the exponential family with any link functions and perform likelihood-based tests of some relevant hypotheses using existing software. We propose the use of a novel visual representation of confidence intervals of the two estimates for the indirect path with the use of a confidence ellipse. The calculation of the confidence ellipse is facilitated by the multivariate approach, can test the components of the composite null hypothesis under a single experiment-wise type I error rate, and does not require estimation of the standard error of the product of coefficients from two separate regressions. This method is illustrated using three examples. The first compares results between the multivariate method and separate regression models. The second example illustrates the proposed methods in the presence of an exposure–mediator interaction, missing data and confounding, and the third example utilizes these proposed methods for an outcome and mediator with negative binomial distributions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Albert JM, Nelson S (2011) Generalized causal mediation analysis. Biometrics 67:1028–1038

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Blood EA, Cabral H, Heeren T, Cheng DM (2010) Performance of mixed effects models in the analysis of mediated longitudinal data. BMC Med Res Methodol 10:16

Brown SA, Gleghorn A, Schuckit MA, Myers MG, Mott MA (1996) Conduct disorder among adolescent alcohol and drug abusers. J Stud Alcohol 57:314–324

Casella G, Berger RL (2002) Statistical inference. Thomson Learning, Pacific Grove, CA

Coffman DL, Zhong W (2012) Assessing mediation using marginal structural models in the presence of confounding and moderation. Psychol Methods 17:642–664

Crowley TJ, Riggs PD (1995) Adolescent substance use disorder with conduct disorder and comorbid conditions. NIDA Res Monogr 156:49–111

Dabelea D, Kinney G, Snell-Bergeon JK, Hokanson JE, Eckel RH, Ehrlich J, Garg S, Hamman RF, Rewers M (2003) Effect of type 1 diabetes on the gender difference in coronary artery calcification: a role for insulin resistance? The coronary artery calcification in type 1 diabetes (CACTI) study. Diabetes 52:2833–2839

Deboer EM, Swiercz W, Heltshe SL, Anthony MM, Szefler P, Klein R, Strain J, Brody AS, Sagel SD (2014) Automated CT scan scores of bronchiectasis and air trapping in cystic fibrosis. Chest 145:593–603

Hayes AF (2009) Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr 76:408–420

Hayes AF, Scharkow M (2013) The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter? Psychol Sci 24:1918–1927

Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D (2010) A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods 15:309–334

Koopman J, Howe M, Hollenbeck JR, Sin HP (2015) Small sample mediation testing: misplaced confidence in bootstrapped confidence intervals. J Appl Psychol 100:194–202

Lange T, Vansteelandt S, Bekaert M (2012) A simple unified approach for estimating natural direct and indirect effects. Am J Epidemiol 176:190–195

Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ (2009) Current directions in mediation analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 18:16

Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS (2007) Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol 58:593–614

Mackinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM (2007) Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: program PRODCLIN. Behav Res Methods 39:384–389

Marshall G, De La Cruz-Mesia R, Baron AE, Rutledge JH, Zerbe GO (2006) Non-linear random effects model for multivariate responses with missing data. Stat Med 25:2817–2830

Mikulich SK, Zerbe GO, Jones RH, Crowley TJ (2003) Comparing linear and nonlinear mixed model approaches to cosinor analysis. Stat Med 22:3195–3211

Pearl J (2001) Direct and indirect effects. In: Proceedings of the seventeenth conference on uncertainty in artificial intelligence. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., Seattle, Washington, pp. 411–420

Pearl J (2010) An introduction to causal inference. Int J Biostat. doi:10.2202/1557-4679.1203

Riggs PD, Winhusen T, Davies RD, Leimberger JD, Mikulich-Gilbertson S, Klein C, Macdonald M, Lohman M, Bailey GL, Haynes L, Jaffee WB, Haminton N, Hodgkins C, Whitmore E, Trello-Rishel K, Tamm L, Acosta MC, Royer-Malvestuto C, Subramaniam G, Fishman M, Holmes BW, Kaye ME, Vargo MA, Woody GE, Nunes EV, Liu D (2011) Randomized controlled trial of osmotic-release methylphenidate with cognitive-behavioral therapy in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50:903–914

Robins JM, Greenland S (1992) Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology 3:143–155

Sagel SD, Wagner BD, Anthony MM, Emmett P, Zemanick ET (2012) Sputum biomarkers of inflammation and lung function decline in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186:857–865

Scheffé H (1959) The analysis of variance. Wiley, New York

Sobel ME (1982) Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhart. S (ed) Sociological methodology. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Taylor AB, Mackinnon DP (2012) Four applications of permutation methods to testing a single-mediator model. Behav Res Methods 44:806–844

Thompson LL, Riggs PD, Mikulich SK, Crowley TJ (1996) Contribution of ADHD symptoms to substance problems and delinquency in conduct-disordered adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 24:325–347

Tofighi D, Mackinnon D (2011) RMediation: an R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behav Res Methods 43:692–700

Tukey JW, Brillinger DR, Cox DR, Braun HI (1984) The collected works of John W. Tukey. Wadsworth Advanced Books & Software, Belmont

Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ (2013) Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods 18:137–150

Vanderweele TJ (2014) A unification of mediation and interaction: a 4-way decomposition. Epidemiology 25:749–761

Vanderweele TJ, Vansteelandt S (2009) Conceptual issues concerning mediation, interventions and composition. Stat Interface 2:457–468

Vanderweele TJ, Vansteelandt S (2010) Odds ratios for mediation analysis for a dichotomous outcome. Am J Epidemiol 172:1339–1348

Young DA, Zerbe GO, Hay WW Jr (1997) Fieller’s theorem, Scheffe simultaneous confidence intervals, and ratios of parameters of linear and nonlinear mixed-effects models. Biometrics 53:838–847

Zerbe GO, Jones RH (1980) On application of growth curve techniques to time series data. J Am Stat Assoc 75:507–509

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants P50 MH086383, K23 RR018611, 2T32AR007534-27, R01 HL113029, R01 HL61753, R01 HL079611, R01 AR051394, R01 DA034604 and R01 DA022284) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (WAGNER15A0).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Derivation of Counterfactual effects for the Generalized Linear Model

Note that many of these effects depend on the chosen values \({A}={a}*\), or \({M}={m}*\), or both.

Recall that

where \(\varphi _a =\theta _2 +\theta _3 a\) denotes the effect of M when \(A=a\), c is a vector of covariates, and \({\beta }'_2 \) and \({\theta }'_4 \) are vectors of regression coefficients.

Note: If the two c’s from M and Y are not the same, we would have to condition on their union.

Controlled Direct Effect defined on the scale of the outcome (inverse link)

where \(h_Y^{-1} \left\{ \right\} \) denotes the inverse function of \(h_Y \left\{ \right\} \) and m is set to a specified value.

Natural direct effect evaluated at \(M=m_\mathrm{a}^{*}\)

where \(m_{a^{*}} =\mathrm{E}\left[ {\mathrm{M\,|\,a}^{\mathrm{*}}\mathrm{,c}} \right] =h_M^{-1} \left\{ {\beta _0 +\beta _1 a^{*}+{\beta }'_2 c} \right\} \).

Natural indirect effect

where \(m_a =h_M^{-1} \left\{ {\beta _0 +\beta _1 a+{\beta }'_2 c} \right\} \),\(m_{a^{*}} =h_M^{-1} \left\{ {\beta _0 +\beta _1 a^{*}+{\beta }'_2 c} \right\} \) and a is set to a specified value when \(\theta _3 \ne 0\).

Total effect

We propose that NIE be used to evaluate whether mediation is present. If there is an interaction, a in \(\varphi _a =\theta _2 +\theta _3 a\) must be specified. If A is dichotomous (say \(A=1\) for males and \(A=0\) for females), then \(\mathrm{NIE}\left( 1 \right) \) could estimate mediation for males and \(\mathrm{NIE}\left( 0 \right) \) for females. If A is continuous, a might be chosen as the mean value of A.

If there is no interaction between the mediator and the exposure (i.e., \(\theta _3 =0)\) and \(\varphi _a =\theta _2 \), then the counterfactuals simplify as follows

If the outcome and the mediator have identity links, such that \({E}\left[ {{Y|a,m,c}} \right] =\theta _0 +\theta _1 a+\theta _2 m+\theta _3 am+{\theta }'_4 c\) and \({E}\left[ {{M|a,c}} \right] =\beta _0 +\beta _1 a+{\beta }'_2 c\), then

as reported by Valeri and VanderWeele [31]. In this case, we propose that in the absence of an interaction, \(\beta _1 \theta _2 \), and in the presence of an interaction, \(\beta _1 \varphi _a \), be used to evaluate whether mediation is present when \(A=a\).

For the case where the outcome is binary and fit using a logistic regression, Valeri and VanderWeele [31] calculate the direct and indirect effect odds ratios. These can be derived from the estimates provided above as follows:

Appendix 2: Comparison of the Standard Errors Computed from the Multivariate Approach Implemented in NLMIXED and the Classical Separate Univariate Regression Method Used in the SAS Macro Provided by Valeri and VanderWeele [31]

Most regression programs, including REG and GENMOD used in SAS Macro provided by Valeri and VanderWeele [31], compute restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimates of the residual variances of the regressions of M on A and Y on A and M, MSE\(_{1}\) and MSE\(_{2}\), respectively. Instead, NLMIXED computes maximum likelihood (ML) estimates \(S_{11 }\) and \(S_{22 }\) such that MSE\(_{1}=n S_{11}/(n-2)\), and MSE\(_{2}=n S_{22}/(n-3)\), where n is the number of subjects. The same proportionality will hold for variances of the regression coefficients. For example, \(\mathrm{SE}_\mathrm{REML} \left( {\hat{{\theta }}_2}\right) =\mathrm{SE}_\mathrm{ML} \left( {\hat{{\theta }}_2 } \right) \sqrt{\frac{\mathrm{n}}{\mathrm{n}-3}}\), and \(\mathrm{SE}_\mathrm{REML} \left( {\hat{{\beta }}_1}\right) =\mathrm{SE}_\mathrm{ML} \left( {\hat{{\beta }}_1}\right) \sqrt{\frac{{n}}{n-2}}\).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wagner, B.D., Kroehl, M., Gan, R. et al. A Multivariate Generalized Linear Model Approach to Mediation Analysis and Application of Confidence Ellipses. Stat Biosci 10, 139–159 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12561-017-9191-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12561-017-9191-2