Abstract

Purpose

Reach of individuals at risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) constitutes a major determinant of the population impact of preventive effort. This study compares three proactive recruitment strategies regarding their reach of individuals with CVD risk factors.

Method

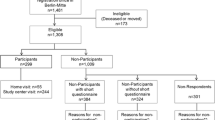

Individuals aged 40–65 years were invited to a two-stage cardio-preventive program including an on-site health screening and a cardiovascular examination program (CEP) using face-to-face recruitment in general practices (n = 671), job centers (n = 1049), and mail invitations from health insurance (n = 894). The recruitment strategies were compared regarding the following: (1) participation rate; (2) participants’ characteristics, i.e., socio-demographics, self-reported health, and CVD risk factors (smoking, physical activity, fruit/vegetable consumption, body mass index, blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and glycated hemoglobin); and (3) participation factors, i.e., differences between participants and non-participants.

Results

Screening participation rates were 56.0, 32.8, and 23.5 % for the general practices, the job centers, and the health insurance, respectively. Among eligible individuals for the CEP, respectively, 80.3, 65.5, and 96.1 % participated in the CEP. Job center clients showed the lowest socio-economic status and the most adverse CVD risk pattern. Being female predicted screening participation across all strategies (OR = 1.45, 95 % CI 1.07–1.98; OR = 1.34, 95 % CI 1.04–1.74; OR = 1.62, 95 % CI 1.16–2.27). Age predicted screening participation only within health insurance (OR = 1.04, 95 % CI 1.01–1.06). Within the general practices and the job centers, CEP participants were less likely to be smokers than non-participants (OR = 0.49, 95 % CI 0.26–0.94; OR = 0.42, 95 % CI 0.20–0.89).

Conclusion

The recruitment in general practices yielded the highest reach. However, job centers may be useful to reduce health inequalities induced by social gradient.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Stampfer MJ, FB H, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:16–22.

Willett WC. Balancing life-style and genomics research for disease prevention. Science. 2002;296:695–8.

Mozaffarian D, Afshin A, Benowitz NL, et al. Population approaches to improve diet, physical activity, and smoking habits: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126:1514–63.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7.

Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Fava JL, et al. Using the transtheoretical model for population-based approaches to health promotion and disease prevention. Homeost Health Dis. 2000;40:174–95.

Gleason K, Shin D, Rueschman M, et al. Challenges in recruitment to a randomized controlled study of cardiovascular disease reduction in sleep apnea: an analysis of alternative strategies. Sleep. 2014;37:2035–8.

Eastwood BJ, Gregor RD, MacLean DR, Wolf HK. Effects of recruitment strategy on response rates and risk factor profile in two cardiovascular surveys. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:763–9.

de Vries H, van ’t Riet J, Spigt M, et al. Clusters of lifestyle behaviors: results from the Dutch SMILE study. Prev Med. 2008;46:203–8.

Hollederer A. Unemployment and health in the German population: results from a 2005 microcensus. Aust J Public Health. 2010;19:257–68.

Freyer-Adam J, Gaertner B, Tobschall S, John U. Health risk factors and self-rated health among job-seekers. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:659.

Freyer-Adam J, Baumann S, Schnuerer I, et al. Does stage tailoring matter in brief alcohol interventions for job-seekers? A randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2014;109:1845–56.

Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. (1993) SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute.

Fuchs R. Änderungsdruck als motivationales Konstrukt: Überprüfung verschiedener Modelle zur Vorhersage gesundheitspräventiver Handlungen [pressure to change as motivational construct: a test of different models to predict health-preventive actions]. Z Sozialpsychol. 1994;25:95–107.

Marcus B, Forsynth L. (2003) Motivating people to be physically active. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

WHO. The WHO STEPwise approach to noncommunicable disease risk factor surveillance (STEPS) Intrument. http://www.who.int/chp/steps/instrument/STEPS_Instrument_V3.1.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 1 Dec 2015).

Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2014;349:g4490.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–357.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52.

WHO. Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: abbreviated report of a WHO consultation. http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/report-hba1c_2011.pdf 2011 (accessed 5 June 2015).

Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L, Morris RW. Metabolic syndrome vs Framingham risk score for prediction of coronary heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2644–50.

Meyer C, Ulbricht S, Schumann A, Rüge J, Rumpf H-J, John U. Proactive smoking interventions to foster smoking cessation in the general medical practice. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. 2008;3:25–30.

Wells BL, Brown CC, Horm JW, Carleton RA, Lasater TM. Who participates in cardiovascular disease risk factor screenings? Experience with a religious organization-based program. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:113–5.

Boshuizen HC, Viet AL, Picavet HS, Botterweck A, van Loon AJ. Non-response in a survey of cardiovascular risk factors in the Dutch population: determinants and resulting biases. Public Health. 2006;120:297–308.

Schneider F, Schulz DN, Pouwels LH, de Vries H, van Osch L. The use of a proactive dissemination strategy to optimize reach of an internet-delivered computer tailored lifestyle intervention. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:721.

Stronks K, van de Mheen HD. Mackenbach JP. A higher prevalence of health problems in low income groups: does it reflect relative deprivation? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:548–57.

Wall M, Teeland L. Non-participants in a preventive health examination for cardiovascular disease: characteristics, reasons for non-participation, and willingness to participate in the future. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2004;22:248–51.

Strine TW, Okoro CA, Chapman DP, et al. Health-related quality of life and health risk behaviors among smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:182–7.

Chapman S, Wong WL, Smith W. Self-exempting beliefs about smoking and health - differences between smokers and ex-smokers. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:215–9.

Bender AM, Jorgensen T, Helbech B, Linneberg A, Pisinger C. Socioeconomic position and participation in baseline and follow-up visits: the Inter99 study. Eur J of Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:899–905.

Burris JE, Johnson TP, O’Rourke DP. Validating self-reports of socially desirable behaviors. American association for public opinion research-section on survey research methods. 2003:32–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by the DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), Grant No. 81/Z540100152.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary table 1

(DOCX 18 kb)

Supplementary table 2

(DOCX 24 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guertler, D., Meyer, C., Dörr, M. et al. Reach of Individuals at Risk for Cardiovascular Disease by Proactive Recruitment Strategies in General Practices, Job Centers, and Health Insurance. Int.J. Behav. Med. 24, 153–160 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9584-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9584-5