Abstract

Background

Excessive alcohol consumption has been linked to deleterious health consequences among undergraduate students. There is a need to develop theory-based and cost-effective brief interventions to attenuate alcohol consumption in this population.

Purpose

The present study tested the effectiveness of an integrated theory-based intervention in reducing undergraduates' alcohol consumption in excess of guideline limits in national samples from Estonia, Finland, and the UK.

Method

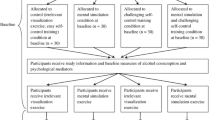

A 2 (volitional: implementation intention vs. no implementation intention) × 2 (motivation: mental simulation vs. no mental simulation) × 3 (nationality: Estonia vs. Finland vs. UK) randomized-controlled design was adopted. Participants completed baseline psychological measures and self-reported number of alcohol units consumed and binge-drinking frequency followed by the intervention manipulation. One month later, participants completed follow-up measures of the psychological variables and alcohol consumption.

Results

Results revealed main effects for implementation intention and nationality on units of alcohol consumed at follow-up and an implementation intention × nationality interaction. Alcohol consumption was significantly reduced in the implementation intention condition for the Estonian and UK samples. There was a significant main effect for nationality and an implementation intention × nationality interaction on binge-drinking frequency. Follow-up tests revealed significant reductions in binge-drinking occasions in the implementation intention group for the UK sample only.

Conclusion

Results support the implementation intention component of the intervention in reducing alcohol drinking in excess of guideline limits among Estonian and UK undergraduates. There was no support for the motivational intervention or the interaction between the strategies. Results are discussed with respect to intervention design based on motivational and volitional approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The measure of motivation correlated significantly with the Theory of Planned Behaviour variables. Correlations between motivation and intention were particularly strong (r range = 0.65 to 0.80), an unsurprising finding given that intention is a motivational variable and reflects the degree of planning and effort an individual is prepared to invest in pursuing the behavior in the future. Taking into consideration the strength of these relations, we exercised care not to include intentions and motivation together as covariates in subsequent analyses in order to avoid potential problems of multi-colinearity.

Previous intervention studies have shown that the significant effects of implementation intention and planning manipulations on alcohol consumption are confined to female samples [41]. This differential effectiveness was a concern in the present study given the variation in gender profiles across the three national samples. One possibility was that the higher proportion of female participants in the UK sample and, to a lesser extent, the Estonian sample, may have accounted for the significant findings for the implementation intention manipulation on the alcohol behavior variables in these samples, relative to the Finnish sample which had the closest ratio of males to females and showed no effects. As a consequence, we conducted supplementary ANCOVAs with gender as an additional independent factor to test the hypothesis that gender moderated the effect of the interventions. Specifically, we conducted two 2 (implementation intention: present vs. absent) × 2 (mental simulation: present vs. absent) × 3 (nationality: Estonia vs. Finland vs. UK) × 2 (gender: male vs. female) ANCOVAs on the dependent variables of average number of units of alcohol and number of binge-drinking occasions in the month following the intervention. The analyses revealed an identical pattern of effects as the main analyses. Specifically, the analysis with number of units consumed as the dependent variable revealed significant main effects for implementation intentions (F(1, 440) = 6.36, p < 0.05, η 2p = 0.01) and nationality (F(2, 440) = 5.42, p < 0.01, η 2p = 0.02), and a significant implementation intention × nationality interaction (F(2, 440) = 5.73, p < 0.01, η 2p = 0.03). The analysis with number of binge-drinking occasions as the dependent variable revealed a significant main effect for nationality (F(1, 440) = 3.60, p < 0.05, η 2p = 0.02) and a significant implementation intention × nationality interaction effect (F(2, 440) = 4.26, p < 0.05, η 2p = 0.02). In both analyses, there was no significant main effect for gender or any effect of the two-, three-, or four-way interactions between gender and the other independent variables on alcohol behavior. These data led us to reject the hypothesis that gender moderated the effects of the intervention components, specifically, implementation intentions, on alcohol behavior.

We also tested whether the inclusion of participants who consumed no alcohol at baseline affected results. Specifically, we conducted analyses on participants reporting drinking at least 1 U of alcohol in the previous 4 weeks at baseline. We conducted two additional 2 (implementation intention: present vs. absent) × 2 (mental simulation: present vs. absent) × 3 (nationality: Estonia vs. Finland vs. UK) ANCOVAs with number of units of alcohol consumed and number of binge-drinking occasions as dependent variables and controlling for baseline FAST scores, alcohol consumption, and attitudes. For the analysis with number of units consumed as the dependent variable, the analysis revealed significant main effects for implementation intention (F(1, 399) = 3.72, p < 0.05, η 2p = 0.01) and nationality (F(2, 399) = 8.21, p < 0.01, η 2p = 0.04), and a significant two-way interaction for implementation intentions and nationality (F(2, 399) = 3.19, p < 0.05, η 2p = 0.02). This interaction was probed with separate univariate ANCOVAs for each national group. The analyses revealed significant main effects for implementation intentions in the Estonia (F(1, 155) = 4.41, p < 0.05, η 2p = 0.03), and UK (F(1, 158) = 10.58, p < 0.01, η 2p = 0.07) samples. For the analysis with number of binge-drinking occasions as the dependent variable, a significant main effect for nationality (F(1, 399) = 6.01, p < 0.01, η 2p = 0.03) and a significant two-way interaction for implementation intentions and nationality (F(2, 399) = 4.27, p < 0.05, η 2p = 0.02) was found. Separate univariate ANCOVAs revealed a similar main effect for implementation intentions as that found previously for the UK sample (F(1, 158) = 6.50, p < 0.05, η 2p = 0.04). There were no other significant effects. These results, therefore, follow a similar pattern to those found in the overall sample.

Mean levels of intentions were significantly higher than the midpoint of the six-point scale for the Estonian (M = 4.74, SD = 1.19; t(1,184) = 14.19, p < 0.01, d = 2.09), Finnish (M = 4.03, SD = 1.73; t(1,118) = 3.37, p < 0.01, d = 0.62), and UK samples (M = 3.96, SD = 1.33; t(1,162) = 4.42, p < 0.01, d = 0.69).

References

Bailer J, Stubinger C, Dressing H, Gass P, Rist F, Kuhner C. Increased prevalence of problematic alcohol consumption in university students. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2009;59:376–9.

Gill JS. Reported levels of alcohol consumption and binge drinking within the UK undergraduate student population over the last 25 years. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:109–20.

Hibell B, Andersson B, Bjarnason T, Ahlström S, Balakireva O, Kokkevi A, et al. The ESPAD report 2003: alcohol and other drug use among students in 35 European countries. Stockholm, Sweden: Pompidou Group at the Council of Europe; 2004.

Plant MA, Plant ML, Miller P, Gmel G, Kuntsche S. The social consequences of binge drinking: a comparison of young adults in six European countries. J Addict Dis. 2009;28:294–308.

Nelson TF, Xuan ZM, Lee H, Weitzman ER, Wechsler H. Persistence of heavy drinking and ensuing consequences at heavy drinking colleges. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:726–34.

Mundt MP, Zakletskaia LI, Fleming MF. Extreme college drinking and alcohol-related injury risk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1532–8.

Cimini MD, Martens MP, Larimer ME, Kilmer JR, Neighbors C, Monserrat JM. Assessing the effectiveness of peer-facilitatied interventions addressing high-risk drinking among judicially mandated college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;16:57–66.

Thombs DL, Olds RS, Bondy SJ, Winchell J, Baliunas D, Rehm J. Undergraduate drinking and academic performance: a prospective investigation with objective measures. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:776–85.

Martinez JA, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is heavy drinking really associated with attrition from college? The alcohol-attrition paradox. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:450–6.

Department of Health. Safe. Sensible. Social. The next steps in the National Alcohol Strategy. London: Home Office; 2009.

Health Challenge Wales and National Union of Students Wales. Don't let your drinking define you. [updated 2009 October 19, 2009; cited 2009 November 1]; Available from: http://www.nus.org.uk/en/News/News/Alcohol-and-the-Student-Experience/;2009.

StudentHealth Ltd. Alcohol and drinking - current daily guidelines for sensible drinking. [updated 2005 August 1, 2005; cited 2009 September 1]; Available from: http://www.studenthealth.co.uk/advice/advice.asp?adviceID=28;2005.

Moore MJ, Soderquist J, Werch C. Feasibility and efficacy of a binge drinking prevention intervention for college students delivered via the Internet versus postal mail. J Am Coll Health. 2005;54:38–44.

Coleman L, Ramm J, Cooke R. The effectiveness of an innovative intervention aimed at reducing binge-drinking among young people: results from a pilot study. Drugs Educ Prev Pol. 2010;17:413–30.

Walters ST, Bennett ME, Miller JH. Reducing alcohol use in college students: a controlled trial of two brief interventions. J Drug Educ. 2000;30:361–72.

Bewick BM, Trusler K, Mulhern B, Barkham M, Hill AJ. The feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based personalised feedback and social norms alcohol intervention in UK university students: a randomised control trial. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1192–8.

Kypri K, Hallett J, Howat P, McManus A, Maycock B, Bowe S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of Proactive web-based alcohol screening and brief intervention for university students. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1508–14.

Butler LH, Correia CJ. Brief alcohol intervention with college student drinkers: face-to-face versus computerized feedback. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:163–7.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:26–33.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27:379–87.

Heckhausen H, Gollwitzer PM. Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational and volitional states of mind. Motiv Emot. 1987;11:101–20.

Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Action-control: from cognition to behavior. Heidelberg: Springer; 1985. p. 11–39.

Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:249–68.

Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001;40:471–99.

Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol. 1999;54:493–503.

Aarts H, Dijksterhuis A, Midden C. To plan or not to plan? Goal achievement or interrupting the performance of mundane behaviors. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1999;29:971–9.

Brandstätter V, Lengfelder A, Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions and efficient action initiation. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2001;81:946–60.

Hardeman W, Johnston M, Johnston DW, Bonetti D, Wareham NJ, Kinmonth AL. Application of the theory of planned behaviour change interventions: a systematic review. Psychol Health. 2002;17:123–58.

Chatzisarantis NLD, Hagger MS. Effects of a brief intervention based on the theory of planned behavior on leisure time physical activity participation. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2005;27:470–87.

Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: a meta-analysis of effects and processes. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;38:69–119.

Sheeran P, Milne S, Webb TL, Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions and health behaviours. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting health behaviour: research and practice with social cognition models. 2nd ed. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2005. p. 276–323.

Arbour KP, Martin Ginis KA. A randomised controlled trial of the effects of implementation intentions on women's walking behaviour. Psychol Health. 2009;24:49–65.

Luszczynska A. An implementation intentions intervention, the use of a planning strategy, and physical activity after myocardial infarction. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:900–8.

Prestwich A, Lawton R, Conner M. The use of implementation intentions and the decision balance sheet in promoting exercise behaviour. Psychol Health. 2003;18:707–21.

Armitage CJ. Effects of an implementation intention-based intervention on fruit consumption. Psychol Health. 2007;22:917–28.

Chapman J, Armitage CJ, Norman P. Comparing implementation intention interventions in relation to young adults' intake of fruit and vegetables. Psychol Health. 2009;24:317–32.

Prestwich A, Ayres K, Lawton R. Crossing two types of implementation intentions with a protection motivation intervention for the reduction of saturated fat intake: a randomized trial. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:1550–8.

Prestwich A, Conner M, Lawton R, Bailey W, Litman J, Molyneaux V. Individual and collaborative implementation intentions and the promotion of breast self-examination. Psychol Health. 2005;20:743–60.

Sheeran P, Orbell S. Using implementation intentions to increase attendance for cervical cancer screening. Health Psychol. 2000;19:283–9.

Orbell S, Hodgkins S, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and the theory of planned behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997;23:945–54.

Murgraff V, Abraham C, McDermott M. Reducing Friday alcohol consumption among moderate, women drinkers: evaluation of a brief evidence-based intervention. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:37–41.

Armitage CJ. Effectiveness of experimenter-provided and self-generated implementation intentions to reduce alcohol consumption in a sample of the general population: a randomized exploratory trial. Health Psychol. 2009;28:545–53.

Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Psychol. 1975;91:93–114.

Janis IL, Mann L. Decision making: a psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. New York: Free Press; 1977.

Milne SE, Orbell S, Sheeran P. Combining motivational and volitional interventions to promote exercise participation: protection motivation theory and implementation intentions. Br J Health Psychol. 2002;7:163–84.

Michie S, Rothman A, Sheeran P. Current issues and new directions in psychology and health: advancing the science of behavior change. Psychol Health. 2007;22:249–53.

Ajzen I, Manstead ASR. Changing health-related behaviors: an approach based on the theory of planned behavior. In: van den Bos K, Hewstone M, de Wit J, Schut H, Stroebe M, editors. The scope of social psychology: theory and applications. New York: Psychology Press; 2007. p. 43–63.

Armitage CJ, Reidy JG. Use of mental simulations to change theory of planned behaviour variables. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13:513–24.

Pham LB, Taylor SE. From thought to action: effects of process- versus outcome-based mental simulations on performance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1999;26:250–60.

Taylor SE, Pham LB, Rivkin I, Armor DA. Harnessing the imagination: mental simulation and self-regulation of behavior. Am Psychol. 1998;53:429–39.

Escalas JE, Luce MF. Process versus outcome thought focus and advertising. J Consum Psychol. 2003;13:246–54.

Elliot AJ, Shell MM, Henry KB, Maier MA. Achievement goals, performance contingencies, and performance attainment: an experimental test. J Educ Psychol. 2005;97:630–40.

Vasquez NA, Buehler R. Seeing future success: does imagery perspective influence achievement motivation? Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2007;33:1392–405.

Hagger MS. Theoretical integration in health psychology: unifying ideas and complimentary explanations. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14:189–94.

Hagger MS, Chatzisarantis NLD, Barkoukis V, Wang CKJ, Baranowski J. Perceived autonomy support in physical education and leisure-time physical activity: a cross-cultural evaluation of the trans-contextual model. J Educ Psychol. 2005;97:376–90.

Anderson P, Baumberg B. Alcohol in Europe. London: Institute of Alcohol Studies; 2006.

Rehn N, Room R, Edwards G. Alcohol in the European region. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation; 2001.

Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:224–53.

Urbaniak GC, Plous S, Lestik M. Research randomiser. [updated 2007 January 1, 1997; cited 2008 March 1]; Available from: www.randomizer.org;2007.

Jackson KM. Heavy episodic drinking: determining the predictive utility of five or more drinks. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:68–77.

Drinkaware. Binge drinking: the facts. [updated 2010; cited 2010 November 1]; Available from: http://www.drinkaware.co.uk/facts/binge-drinking;2010.

Hodgson RJ, Alwyn T, John B, Thom B, Smith A. The fast alcohol screening test. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:61–6.

Schulte MT, Ramo D, Brown SA. Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:535–47.

Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark CB, Geisner IM, et al. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:285–93.

Hardeman W, Michie S, Fanshawe T, Prevost T, Mcloughlin K, Kinmonth AL. Fidelity of delivery of a physical activity intervention: predictors and consequences. Psychol Health. 2007;23:11–24.

De Vet E, Oenema A, Sheeran P, Brug J. Should implementation intentions interventions be implemented in obesity prevention: the impact of if-then plans on daily physical activity in Dutch adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2009;6:11.

Godin G, Sheeran P, Conner M, Germain M. Asking questions changes behavior: mere measurement effects on frequency of blood donation. Health Psychol. 2008;27:179–84.

O'Sullivan I, Orbell S, Rakow T, Parker R. Prospective research in health service settings: health psychology, science and the ‘Hawthorne’ effect. J Health Psychol. 2004;9:355–9.

McCambridge J, Day M. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of completing the alcohol use disorders identification test questionnaire on self-reported hazardous drinking. Addiction. 2008;103:241–8.

Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Funder DC. Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: whatever happened to actual behavior? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:396–403.

Cooke R, Sniehotta F, Schuz B. Predicting binge-drinking behaviour using an extended TPB: examining the impact of anticipated regret and descriptive norms. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:84–91.

Murgraff V, McDermott MR, Walsh J. Exploring attitude and belief correlates of adhering to the new guidelines and low-risk single-occasion drinking: an application of the theory of planned behaviour. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001;36:135–40.

Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa: Humana Press; 1992.

Chatzisarantis NLD, Hagger MS. Effects of an intervention based on self-determination theory on self-reported leisure-time physical activity participation. Psychology and Health. 2009;24(1):29–48.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research was supported by grant #EA 07 10 from the European Research Advisory Board awarded to Martin S. Hagger.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Introductory Passage

Initial introductory passage provided to participants allocated to the implementation intention and mental simulation conditions:

“The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that safe limits for drinking alcoholic drinks are 4 U per day for men and 3 U per day for women. Drinking above these safe limits could lead to some health conditions in the long run. Considering these health messages, we would like you to try to keep your regular alcohol intake so that it is within recommended limits on each individual occasion or session over the next month. To help you do this, we ask you to take 5 min of your time to complete the next very simple mental exercise(s)”.

Implementation Intention Manipulation

“You are more likely to carry out your intention to keep your alcohol intake to within safe limits on each occasion or session if you make a decision about the time and place you will do so and how you plan to do it. Decide now when and where you will need to keep your alcohol intake to within safe limits and how you will do it. We want you to plan to keep your alcohol drinking to within safe limits on each occasion or session over the next month, paying particular attention to the specific situations in which you will implement these plans. For example, you may find it useful to say to yourself, ‘If I am in a bar/pub drinking with my friends and I am likely to drink over the daily safe limits for alcohol, then I will opt for a soft drink instead of an alcoholic drink to keep within the recommended safe limits.’ Please write your plans on the lines below, following the format shown in the previous example (‘if… then…’).”

Mental Simulation Manipulation

“You are now asked to visualize yourself having achieved your goal of keeping your alcohol intake to within safe limits on each individual occasion or session over the next month, and imagine how you would feel. Imagine how much effort and willpower it has taken to achieve your goal of keeping your alcohol intake to within safe limits on each occasion or session and that you have successfully managed to do it. Imagine how satisfied you will feel. It is very important that you see yourself actually keeping your alcohol intake to within safe limits on each occasion or session over the next month and keep that picture on your mind. Please write on the lines below how you imagine will feel if you achieve your goal of keeping your alcohol intake within safe limits on each individual occasion or session over the next month.”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hagger, M.S., Lonsdale, A., Koka, A. et al. An Intervention to Reduce Alcohol Consumption in Undergraduate Students Using Implementation Intentions and Mental Simulations: A Cross-National Study. Int.J. Behav. Med. 19, 82–96 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9163-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9163-8