Abstract

Introduction

The objective of this subgroup analysis is to investigate the effectiveness of liraglutide in people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) treated within the primary care physician (PCP) and specialist care settings.

Methods

EVIDENCE is a prospective, observational study of 3152 adults with T2D recently starting or about to start liraglutide treatment in France. We followed patients in the PCP and specialist settings for 2 years to evaluate the effectiveness of liraglutide in glycemic control and body weight reduction. Furthermore, we evaluated the changes in combined antihyperglycemic treatments, the reasons for prescribing liraglutide, patient satisfaction, and safety of liraglutide in these two treatment settings.

Results

After 2 years of follow-up, 477 out of 1209 (39.0%) of PCP and 297 out of 1398 (21.2%) of specialist-treated patients still used liraglutide and maintained the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) target of <7.0%. Significant reductions from baseline were observed in both PCP- and specialist-treated cohorts in mean HbA1c (−1.22% and −0.8%, respectively), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) concentration (−39 and −23 mg/dL), body weight (−4.4 and −3.8 kg), and body mass index (BMI) (−1.5 and −1.4 kg/m2), all p < 0.0001. Reductions in HbA1c and FPG were significantly greater among PCP- compared with specialist-treated patients, p < 0.0001 for both. Patient treatment satisfaction was also significantly increased in both cohorts. Reported gastrointestinal adverse events were less frequent among PCP-treated patients compared with specialist-treated patients (4.5% vs. 16.1%).

Conclusion

Despite differences in demography and clinical characteristics of patients treated for T2D in PCP and specialty care, greater reduction in HbA1c and increased glycemic control durability were observed with liraglutide in primary care, compared with specialist care. These data suggest that liraglutide treatment could benefit patients in primary care by delaying the need for further treatment intensification.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01226966.

Funding

Novo Nordisk A/S.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes (T2D) depends upon on a variety of patient- and disease-specific factors [1]. In the case of metformin not being sufficient to achieve appropriate glycemic control, patients require intensification by adding a new therapeutic agent. One option recommended by the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) position statement and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) guidelines is the introduction of a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) as a second-line therapy [1, 2]. In the case of the AACE/ACE guidelines, GLP-1RAs are the first-choice second-line therapy. Liraglutide is a once-daily GLP-1RA for the treatment of T2D that has been shown to offer effective glycemic control, benefits in body weight reduction, improved measures of β-cell function, and a low risk of hypoglycemia. This was demonstrated in the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes (LEAD) phase 3 randomized clinical trials (RCT) program, in which liraglutide was used both as monotherapy and combined with other glucose-lowering agents [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Recently, a cardiovascular outcomes trial to determine the long-term effects of liraglutide on cardiovascular safety in patients with T2D at high cardiovascular risk (LEADER) showed that liraglutide significantly reduced the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events [10].

Compared with RCTs, observational studies are conducted with less strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Furthermore, they are less costly and can be used to study larger numbers of people in a wider range of environments. This provides crucial real-world evidence (RWE) from routine clinical practice that may be generalized to a broader population, despite that they provide less monitoring of patients, which may result in under-reporting of adverse events (AEs) [11, 12]. Results from the EVIDENCE study have already been published, showing the effectiveness of liraglutide in real-world clinical practice to be similar to that observed in RCTs, but with a lower incidence of gastrointestinal AEs [13]. However, these data previously amalgamated outcomes in patients prescribed liraglutide by (and followed by) both primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists (diabetologists and endocrinologists). Given that the majority of patients with T2D are treated in a PCP setting, PCPs play a crucial role at the front-line of T2D management in the earlier stages of the disease. Patients treated by PCPs are likely to be characterized differently from patients managed in a specialist setting in regards to demographic and clinical distinctions; therefore, it is of clinical interest to assess the real-world effectiveness of liraglutide in these patients separately. The aim of the present subgroup analysis is to examine the effectiveness of liraglutide in the two specific patient subgroups that constitute the original study cohort: those treated by PCPs and those treated by specialists.

Methods

The study methodology has been outlined previously [13] and is summarized below. All procedures followed were in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Declaration of Helsinki, 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for participation in the study.

Study Design

The observational, prospective, multicenter EVIDENCE study was conducted in France between September 2010 and November 2013, in adults with T2D who had recently started or were about to start treatment with liraglutide [13]. PCPs and specialists already treating patients with diabetes and prescribing injectable antihyperglycemic treatments were randomly recruited and asked to include the first two or three consecutive patients meeting the eligibility criteria. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were published previously [13]. Data related to glycemic control, AEs (including medical events of special interest [MESI]), demographic characteristics, vital signs, and treatment satisfaction were collected by physicians during routine care at inclusion (visit 1), then at approximately 3 months (visit 2), 6 months (visit 3), 12 months (visit 4), 18 months (visit 5), and 24 months (visit 6).

Outcome Measures

Endpoints in this subgroup analysis are the same as those evaluated in the original EVIDENCE study, but specified for the PCP and specialist patient subgroups [13]. The primary endpoint of the original study was the percentage of patients still using liraglutide and meeting the ADA target of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) <7.0% [1] at 2 years of follow-up.

Secondary endpoints included change in antihyperglycemic treatment, change in HbA1c, change in fasting plasma glucose (FPG), change in body weight and body mass index (BMI), patient satisfaction with diabetes treatment as measured using the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) and DTSQ change, evaluation of the reasons for prescription of liraglutide, and safety of liraglutide (hypoglycemic episodes, AEs, and MESI). Hypoglycemic episodes within the 4 weeks preceding each visit were reported by the patients and classified as minor (not requiring third-party intervention) or major/severe (requiring third-party intervention). MESI included pancreatitis, thyroid gland anomalies, malignant neoplasias, and major hypoglycemic events.

Definition of Study Populations

The EVIDENCE cohort was divided into multiple analysis sets. Definitions of the different analysis sets visit have been outlined previously [13], but briefly: the full analysis set (FAS) included all patients attending the inclusion visit and for whom liraglutide was prescribed; the effectiveness analysis set (EAS) included all patients already included in the FAS who completed the 2-year final visit under treatment with liraglutide, and with at least one measurement of HbA1c, FPG, body weight, or hypoglycemia information at the end of the study; the population for primary endpoint analysis (PEA) included all EAS patients plus patients discontinuing liraglutide treatment but who remained in the study; and the patient-reported outcomes analysis set (PROAS) included all patients in the FAS who also filled in at least one item on the patient questionnaire at the inclusion visit and at least one follow-up. Changes in HbA1c, FPG concentration, body weight, and BMI from baseline to 2 years were analyzed using the EAS population, whereas baseline characteristics, change in treatment, motivating factors (for prescription of liraglutide), and AEs were all analyzed using the FAS population.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical methodology was described previously for the overall patient cohort [13]. The present subanalysis examines changes from baseline to end-of-study in the two separate patient cohort subgroups, treated in the PCP and specialist settings, in the same way as the original overall analysis [13]. In addition, between-group statistical comparisons of both baseline characteristics and secondary efficacy endpoints using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Chi2 test (for dichotomous variables) were performed.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of patients from the PCP (N = 1398) and specialist (N = 1754) cohorts are presented in Table 1. PCP-treated patients were on average significantly older (60.1 vs. 57.6 years, p < 0.0001), significantly more likely to be male (55.7% vs. 50.9%, p < 0.01), and had a significantly shorter duration of diabetes (8 vs. 10 years, p < 0.0001), significantly lower body weight (92.6 vs. 98.1 kg, p < 0.0001), significantly lower BMI (32.8 vs. 35.1 kg/m2, p < 0.0001), and similar HbA1c (8.53% vs. 8.56%, p = 0.83) and FPG levels (182 vs. 182 mg/dL, p = 0.58) compared with specialist-treated patients. The proportion of patients with at least one complication at baseline was lower in the specialist-treated cohort compared with the PCP-treated cohort (28.3% vs. 37.6%).

Primary Endpoint

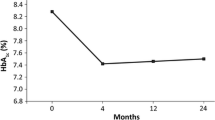

In total, 472 out of 1209 patients (39.0%) of the PCP-treated PEA population were still treated with liraglutide and achieved the target of HbA1c <7.0% at 2 years of follow-up. In comparison, 297 out of 1398 patients (21.2%) in the specialist cohort were still treated with liraglutide and achieved the target of HbA1c <7.0% at the end of the study (Fig. 1). In total (based on a percentage of the complete analysis population, FAS), 1054 PCP-treated patients (75.4%) and 975 specialist-treated patients (55.6%) completed 2 years of liraglutide treatment.

Secondary Endpoints

Change in Antihyperglycemic Treatment from Baseline

An average 29.1% of PCP-treated patients were on monotherapy before liraglutide initiation, compared with only 11.0% among the specialist-treated patients; 43.2% of PCP-treated patients had been on a combination of two drugs when liraglutide was initiated. In the specialist-treated cohort, the majority of patients were treated with three or more agents when initiating liraglutide (Table 2). Approximately half the number of PCP-treated patients were taking insulin before initiation of liraglutide compared with specialist-treated patients (8.1% vs. 18.2%). After 2 years, these proportions remained fairly similar, with a greater proportion of specialist-treated patients than PCP-treated patients taking more than three therapies (13.4% vs. 28.5%). After 2 years, the proportion of specialist-treated patients using insulin had increased to 35.8%, a markedly greater increase than that seen among PCP-treated patients (to only 13.6% of patients).

The need to improve glycemic (80.8% vs. 81.4%) and body weight control (58.7% vs. 74.0%) was the most common strongest motivation given for prescription of liraglutide in PCP and specialist cohorts, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).

Glycemic and Body Weight Control

Changes in HbA1c, FPG concentration, body weight, and BMI from baseline to 2 years were analyzed on the basis of data from the EAS population. From baseline to end of study, a significant mean reduction in HbA1c was observed in PCP- and specialist-treated patients (−1.22% and −0.80%, respectively, p < 0.0001 for both, Table 3). Mean FPG reduction from baseline was significant: −39 mg/dL in PCP-treated patients and −23 mg/dL among specialist-treated patients (p < 0.0001 for both). Changes in HbA1c and FPG from baseline were significantly greater for PCP-treated patients compared with those treated by specialists, p < 0.0001 for both. Body weight (−4.4 and −3.8 kg) and mean BMI (−1.5 and −1.4 kg/m2) were also significantly reduced from baseline in both PCP- and specialist-treated patients (all p < 0.0001, Table 3). Reductions from baseline, although numerically greater within the PCP cohort, were not significantly greater than that seen among specialist-treated patients (p = 0.09 for weight and p = 0.15 for BMI).

Treatment Satisfaction

Throughout the study, patient treatment satisfaction with liraglutide in PCP-treated patients increased with an initial DTSQ status score by 7.52, from a mean (±SD) of 20.75 ± 6.93 (range 1.0–36.0) at baseline to 28.27 ± 5.57 (range 7.0–36.0) at the end of the study (p < 0.0001). In specialist-treated patients, there was an increase of 5.47, from 23.47 ± 8.02 (range 0.0–36.0) at baseline to 28.95 ± 6.07 (3.0–36.0) at the end of the study after 24 months (p < 0.0001).

Change in satisfaction with treatment (compared with previous treatment) after 1 year follow-up, measured by the DTSQ change, was improved on average 10.54 ± 5.69 (range 10.13–10.96) among PCP-treated patients and 10.89 ± 6.49 (range 10.40–11.37) among those treated by specialists.

Hypoglycemia

The percentage of PCP-treated patients with at least one episode of hypoglycemia (within 4 weeks prior to each visit) decreased during the study, from 2.8% at 3 months to 1.0% at the end of the study. Among specialist-treated patients, incidence of hypoglycemia also decreased, from 11.4% to 7.9%. Major hypoglycemia was very rare with a slight increase in incidence from 0.1% to 0.3%, and decrease from 0.2% to 0.0% in PCP and specialist-treated patients, respectively.

Adverse Events and MESI

In total, at least one AE was reported in 158 (11.3%) and 495 (28.2%) PCP-treated and specialist-treated patients, respectively, during the study period. AE categories affecting at least 1.0% of the population are listed in Table 4.

In addition, there was one serious AE of nausea observed in each subgroup. The most commonly reported AEs in both subgroups were gastrointestinal in nature, with a frequency of 4.5% in the PCP cohort and 16.1% in the specialist cohort. Four cases of acute pancreatitis were observed in the specialist cohort in addition to one case of chronic pancreatitis reported in both cohorts. One pancreatic neoplasm was observed in one patient within the specialist-treated cohort.

Discussion

Liraglutide treatment was associated with sustained glycemic control both in PCP and specialist settings, with 39.0% of PCP-treated patients and 21.2% of specialist-treated patients still under treatment and achieving HbA1c <7.0% after 2 years of follow-up. This highlights that PCP-treated as well as specialist-treated patients can both meet glycemic targets and maintain control over extended periods of time, rather than for the usually shorter period of an RCT.

Importantly, for all clinical outcomes, patients included in this PCP cohort showed more favorable clinical responses than the specialist cohort, most notably in HbA1c and FPG responses, for which the reductions were significantly greater among PCP-treated patients. This suggests that the specialist-treated cohort may have included those selected patients who had previously been more challenging to treat in primary practice. The more challenging nature of the specialist-treated cohort is evidenced by the fact that there were several baseline differences between the cohorts in this study: PCP-treated patients, on average, had a significantly shorter duration of diabetes, significantly lower BMI, and fewer complications compared with specialist-treated patients. Furthermore, more patients used liraglutide in addition to three or more than three therapies, or in combination with insulin, if they were treated by specialists, indicating that these patients had a more complex disease history than those treated in the PCP setting. This is also reflected by previous oral antidiabetic drug monotherapy being more common among PCP-treated patients than specialist-treated patients before initiation of liraglutide. Over the 2 years of follow-up, concomitant antihyperglycemic therapy evolved steadily in both subgroups, underlining the progressive course of disease in both groups. Notably, the proportion of specialist-treated patients taking insulin after 2 years had increased markedly.

There is already a wealth of RWE on the effectiveness of liraglutide showing it to be effective in reducing and maintaining reductions in HbA1c and body weight in different contexts, including Indian [14], Japanese [15], and European [16] populations, in some cases up to 3 years post-treatment initiation [17]. These findings were verified in a recent systematic review of observational data [18]. Real-life clinical data assessed in an audit by The Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) demonstrated that, after 6 months of treatment, liraglutide had effectively reduced HbA1c and was well tolerated [19, 20]. Additionally, data from the IMS Health integrated claims database in the USA demonstrated that, in clinical practice, liraglutide provides greater HbA1c reductions and achievement of glycemic target compared with exenatide and the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor sitagliptin, in patients with T2D [21].

The results of this subgroup analysis of the EVIDENCE study suggest that liraglutide, when prescribed by and followed by a PCP in real-life practice, has an effectiveness and safety profile consistent with that observed in RCTs [3,4,5,6,7,8,9] as well as RWE studies [19,20,21], indicating that liraglutide is effective in achieving target and maintaining glycemic control in the long term in a PCP management setting. The achievement of significantly greater reductions in HbA1c and FPG in the PCP setting is likely to be related to patient baseline characteristics, but may also indicate that empowerment of PCPs to initiate liraglutide treatment at an earlier stage could reduce the chance of developing complications, by achieving greater and prolonged HbA1c reductions.

In the current study, patients in both cohorts were, on average, slightly older and with a higher prevalence of obesity than those included in the LEAD studies, where mean age was 55.7 years and mean BMI 31.9 kg/m2 [22]. Additionally, a number of both PCP- and specialist-treated patients had previously been treated with insulin prior to liraglutide initiation in the EVIDENCE study, which was considered as an exclusion criterion for the LEAD studies [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The median duration of diabetes in patients included in the EVIDENCE study was 8 years (PCP cohort) and 10 years (specialist cohort), compared with 5.4–9.4 years in the LEAD studies [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. This suggests that liraglutide was initiated at a later stage of the disease in the EVIDENCE study compared with the LEAD studies [13]. However, the baseline HbA1c levels were similar in the EVIDENCE (8.5%) and LEAD (ca. 8.4%) studies [22], highlighting the issue of clinical inertia [23], with delayed treatment intensification despite suboptimal glycemic control, for patients with T2D in the real-world setting. The mean reduction in HbA1c observed at the end of the EVIDENCE study for PCP- and specialist-treated patients was clinically relevant and comparable to that observed in the LEAD program [3,4,5,6,7,8,9] and in more recent studies with liraglutide [24, 25], suggesting that clinically relevant reductions in HbA1c can be achieved in the real world and that the findings may be generalized to wider populations.

Although improvement in glycemic control was the main reason for prescription of liraglutide, there was a higher proportion of PCPs as well as specialist care who cited “improvement in body weight control” as a desired effect. In total, 63.4% and 76.7% of PCP- and specialist-treated patients, respectively, had an initial BMI ≥30 kg/m2, and reductions in body weight and BMI after 2 years’ follow-up were statistically significant for both cohorts and consistent with those reported in RCTs [3,4,5,6,7,8,9] and other studies assessing the effectiveness of liraglutide [24, 25].

The safety profile of liraglutide in both cohorts was consistent with previous results. However, of note is the discrepancy in the rate of gastrointestinal AEs between the two cohorts, with a greater proportion of specialist-treated patients reporting AEs. In addition, hypoglycemia rates differed between cohorts; this might reflect the greater use of insulin in specialist-treated patients, and the perhaps unexpected decline in hypoglycemia in this cohort might reflect the insulin dose-sparing effect of liraglutide. Unfortunately, a limitation of this analysis is the lack of information on average dose of insulin, which might have added information to further understand this issue. Alternatively, the difference in rate of hypoglycemia could be attributed to differences in the way PCPs and specialists reported hypoglycemia—the design of the study did not include any hypoglycemia verification test, allowing for this possibility. Furthermore, on the basis of the limitations of an observational study, this study may also be subject to confounding and selection bias.

Conclusion

The results of this subgroup analysis highlight the effectiveness of liraglutide in terms of sustained glycemic control and body weight reduction in patients with T2D treated both in the PCP and specialist settings, consistent with results from RCTs and other RWE studies. In addition, patients treated in the PCP setting obtained significantly more favorable glycemic outcomes in terms of HbA1c reduction and glycemic control durability than those treated by specialists. Patients treated in a PCP setting also showed less of a tendency to progress to more complex treatment regimens. Overall, these results suggest that liraglutide treatment could benefit patients in the primary care setting by delaying the need for further treatment intensification.

References

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centred approach. Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;58:429–42.

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2016 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:84–113.

Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet. 2009;374:39–47.

Croom KF, McCormack PL. Liraglutide: a review of its use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2009;69(14):1985–2004.

Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373:473–81.

Marre M, Shaw J, Brandle M, et al. Liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analogue, added to a sulphonylurea over 26 weeks produces greater improvements in glycaemic and weight control compared with adding rosiglitazone or placebo in subjects with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-1 SU). Diabet Med. 2009;26:268–78.

Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)-2 study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:84–90.

Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met+ SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2046–55.

Zinman B, Gerich J, Buse JB, et al. Efficacy and safety of the human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog liraglutide in combination with metformin and thiazolidinedione in patients with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-4 Met + TZD). Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1224–30.

Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311–22.

MacMahon S, Collins R. Reliable assessment of the effects of treatment on mortality and major morbidity, II: observational studies. Lancet. 2001;357:455–62.

Yang W, Zilov A, Soewondo P, Bech OM, Sekkal F, Home PD. Observational studies: going beyond the boundaries of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88(Suppl 1):S3–9.

Gautier JF, Martinez L, Penfornis A, et al. Effectiveness and persistence with liraglutide among patients with type 2 diabetes in routine clinical practice—EVIDENCE: a prospective, 2-year follow-up, observational, post-marketing study. Adv Ther. 2015;32:838–53.

Kesavadev J, Shankar A, Krishnan G, Jothydev S. Liraglutide therapy beyond glycemic control: an observational study in Indian patients with type 2 diabetes in real world setting. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:317–22.

Inoue K, Maeda N, Fujishima Y, et al. Long-term impact of liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue, on body weight and glycemic control in Japanese type 2 diabetes: an observational study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6:95.

Buysschaert M, D’Hooge D, Preumont V, Roots Study Group. ROOTS: a multicenter study in Belgium to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of liraglutide (Victoza®) in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2015;9:139–42.

Ponzani P, Scardapane M, Nicolucci A, Rossi MC. Effectiveness and safety of liraglutide after three years of treatment. Minerva Endocrinol. 2016;41:35–42.

Ostawal A, Mocevic E, Kragh N, Xu W. Clinical effectiveness of liraglutide in type 2 diabetes treatment in the real-world setting: a systematic literature review. Diabetes Ther. 2016;7:411–38.

Thong K, Walton C, Ryder R. Safety and efficacy of liraglutide 1.2 mg in patients with mild and moderate renal impairment: the ABCD nationwide liraglutide audit. Pract Diabetes. 2013;30:71-6b.

Thong K, Gupta PS, Cull ML, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes-NICE guidelines versus clinical practice. Br J Diabetes. 2014;14:52–9.

Lee WC, Dekoven M, Bouchard J, Massoudi M, Langer J. Improved real-world glycaemic outcomes with liraglutide versus other incretin-based therapies in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:819–26.

Montanya E, Fonseca V, Colagiuri S, Blonde L, Donsmark M, Nauck MA. HbA improvement evaluated by baseline BMI: a meta-analysis of the liraglutide phase 3 clinical trial programme. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;18:707–10.

Khunti K, Wolden ML, Thorsted BL, Andersen M, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia in people with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study of more than 80,000 people. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3411–7.

Nyeland ME, Ploug UJ, Richards A, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of liraglutide and sitagliptin in type 2 diabetes: a retrospective study in UK primary care. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:281–91.

Mezquita-Raya P, Reyes-Garcia R, Moreno-Perez O, et al. Clinical effects of liraglutide in a real-world setting in Spain: eDiabetes-Monitor SEEN Diabetes Mellitus Working Group Study. Diabetes Ther. 2015;6:173–85.

Acknowledgements

This study, the article processing charges, and open access fee for this publication were sponsored by Novo Nordisk A/S. All named authors met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and gave final approval for the version to be published. The authors would like to thank all investigators, patients, and study coordinators involved in the EVIDENCE study, and Nathan Ley of Watermeadow Medical, UK, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, for providing medical writing and editorial assistance to the authors during the preparation of this manuscript, funded by Novo Nordisk. We also thank Salvatore Calanna, Emina Mocevic, and Helge Gydesen of Novo Nordisk for their review and input to the manuscript.

Disclosures

L. Martinez: consultant/Advisor for Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, GlaxoSmithKline, Ipsen; Lilly, Mayoly Spindler, Menarini, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer Inc, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur MSD, and Servier. A. Penfornis: received fees for consultancy, advisory boards, speaking, travel, or accommodation from Bayer, LifeScan, Sanofi, Lilly, Takeda, Janssen, Novartis, MSD, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Novo Nordisk, and Medtronic. J.-F. Gautier: received consulting honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier. He has received speaking fees from AstraZeneca/Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli-Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Servier. He has received research grants from Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi, and received travel grants from Janssen, AstraZeneca/Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Sanofi E. Eschwège: member of the scientific committee of EVIDENCE without fees from Novo Nordisk. G. Charpentier: member of Novo Nordisk scientific board. A. Bouzidi: employee of Novo Nordisk and shareholder in the company. P. Gourdy: received consulting and lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli-Lilly, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Servier, and Takeda, and research grants from AstraZeneca and Sanofi.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Declaration of Helsinki, 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Luc Martinez: Retired from Université Pierre and Marie Curie.

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/2967F0607DC592C4.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Martinez, L., Penfornis, A., Gautier, JF. et al. Effectiveness and Persistence of Liraglutide Treatment Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Treated in Primary Care and Specialist Settings: A Subgroup Analysis from the EVIDENCE Study, a Prospective, 2-Year Follow-up, Observational, Post-Marketing Study. Adv Ther 34, 674–685 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0476-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0476-0