Abstract

The playing field is a concept often used to describe level of fairness in electoral competition. With Levitsky and Way’s definition of the playing field as a case in point, this paper takes a critical look at existing work on the playing field, arguing that current conceptualizations suffer from lacking conceptual logic, operationalization and measurement. A new and disaggregated framework that can serve as the basis for future research on the playing field is then proposed. This framework is applied to an illustrative case study on the development of the playing field in Zambia under MMD rule, thereby demonstrating that it is able to capture both the changing nature of the playing field and the differing mechanisms at play to a larger degree than the framework put forth by Levitsky and Way. The 2011 elections in Zambia also clearly highlight the importance of conceptually and empirically separating the slope of the playing field from its impact on both the opposition and electoral outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The past 25 years have seen a large increase in the number of regimes that hold multiparty elections but do not conform to international standards when it comes to the conduct of elections, access to political rights, and civil liberties (Carothers 2002; Hadenius and Teorell 2007). Nowhere in the world are these regimes as prevalent as Sub-Saharan Africa: “The reality across the sub-continent is clearly one of ‘hybrid regimes’” (Lynch and Crawford 2011, p. 281). Despite the “routinisation of elections” (van de Walle 2003, p. 299) on the continent, the majority of these elections take place in contexts where incumbency advantages are extreme due to excessively strong executives (Rakner and van de Walle 2009, p. 112).

This trend has coincided with increasing use of the concept of the playing field to evaluate electoral quality. Often, and especially in less developed countries, election monitoring reports and the media claim that the lack of an even playing field compromised the quality of a given election because it prevented fair competition between the incumbent and the opposition (Levitsky and Way 2010b, p. 57; Merloe 1997; Schedler 2006, p. 1). General agreement exists among both scholars and election observers that a relatively even playing field between parties and candidates competing in an election is essential for fair competition (cf. Bjornlund 2004; Goodwin-Gill 1998). However, left unresolved are what the concept of the playing field entails within the context of electoral competition, which components are part of the concept, which indicators can measure its evenness and how these indicators should be aggregated. The result has been widespread use of a concept (especially in the media and election monitoring reports) without consensus on what this concept entails or how it should be measured and applied.

Levitsky and Way (2002, 2010a, 2010b) have changed this through their work on competitive authoritarianism. They argue that in addition to free and fair elections and civil liberties, an even playing field—defined as equal access to resources, media and the law—is essential for democracy, making the presence of an uneven playing field a hallmark of a competitive authoritarian regime (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 7, 2010b, p. 63). Their work has provided a clear purpose and analytical tools for this concept but as this paper will highlight, it falls short of actually measuring the playing field. Building on Levitsky and Way’s work, this paper proposes a framework that can be used to anchor an analysis of the evenness of the playing field. After a brief review of existing work on the concept, a critique of Levitsky and Way’s conceptualization and measurement is presented. Subsequently, an alternative, disaggregate framework for measuring the playing field is proposed and discussed before it is presented and applied in a study of the playing field under the competitive authoritarian Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) regime that held power in Zambia from 1991 until 2011.

The analysis highlights several advantages of this framework relative to that of Levitsky and Way: (1) The importance of separating the evenness of the playing field from its effects on political actors, as emphasized by the fact that the playing field was more even in the 2006 election when the MMD retained power compared to 2011, when it lost. (2) That a dichotomous measure of the playing field as either even or uneven as proposed by Levitsky and Way hides important variation between elections in Zambia. (3) Although changes in the evenness of the different attributes of the playing field are relatively synchronized, the initial analysis indicates that there are different dynamics driving these changes for each attribute, implying that a disaggregated framework is fruitful. The Zambian case thus illustrates that the framework proposed here leads to different conclusions and different avenues for future research than do existing studies of the playing field.

2 Understanding the playing field

The traditional use of the playing field as a concept can be found in discussions on distributive justice, especially concerning the important principle of equality of opportunity (e.g. Roemer 1998). The notion here is that “justice requires levelling the playing field by rendering everyone’s opportunities equal in an appropriate sense, and then letting individual choices and their effects dictate further outcomes” (Arneson 2008, p. 16). Equality of opportunity thus focuses on the opportunity of individuals to make informed decisions through (1) eliminating initial inequalities not chosen by the individual, and (2) providing fair conditions for interaction. The focus on fair interaction is key to understanding the link between an even playing field and democratic electoral competition. As Bartolini (1999, 2000) notes, competition is a central aspect of democracy. However, for competition to be democratic it depends on contestability. Contestability focuses on the fairness of the political contest between political actors. One of the issues Bartolini highlights as imperative for fairness is “the possibility of accessing resources necessary for an electoral race with the other” (Bartolini 1999, p. 457). Thus in Bartolini’s conceptualization of democracy, the playing field is a key issue.

Within the context of real life electoral contests, a “level playing field” has since the 1990s been used to denote a situation where no group participating in an election has a better chance at winning as a result of unfair conditions (Elklit and Svensson 1997, p. 36; see also Goodwin-Gill 1998; Merloe 1997; Gould and Jackson 1995). However, early work on the playing field was often focused strictly on a narrow, pre-election time period and on formal and legal factors, thus failing to be of significant analytical value.

Levitsky and Way correct many of the mistakes in early work on the playing field by giving the concept a clear purpose. They argue that the central point is whether or not the playing field is even. This, they contend, can be determined by identifying where “the opposition’s ability to organize and compete in elections is seriously handicapped” (Levitsky and Way 2010b, p. 58) as a result of incumbency advantage throughout the electoral cycle (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 6). The authors then specify the advantages crucial for the playing field:

We define an uneven playing field as one in which incumbent abuse of the state generates such disparities in access to resources, media, or state institutions that opposition parties’ ability to organize and compete for national office is seriously impaired. (Levitsky and Way 2010b, p. 57)

Thus the playing field is fundamentally about incumbents’ abuse of state power in order to generate relative differences in access to resources, media and the lawFootnote 1 between the incumbent and opposition, both during and between elections. The attributes of this concept—access to resources, media and the law—are largely in tune with the wider literature on electoral competition under authoritarianism, which highlights access to resources, media and the law as central factors for understanding the fairness of political competition and subsequently the degree of control enjoyed by the incumbent (cf. Gandhi and Lust-Okar 2009; Morgenbesser 2013; Morse 2012; Schedler 2013).Footnote 2 To measure the concept, Levitsky and Way (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 368) further operationalize it by creating an indicator per attribute (with subcomponents), adding that a violation of any indicator is sufficient to score the playing field as uneven. In terms of access to resources, an uneven playing field is present if the incumbent makes widespread use of public resources or uses public tools to limit or skew access to private-sector finance. Concerning access to media, the playing field is uneven if state-owned media is the primary source of news and biased towards the incumbent, or if private media is manipulated through various mechanisms. While these operationalizations are clear, the operationalization of the third attribute, access to law, is somewhat problematic. This problem is linked to the first of my three criticisms of Levitsky and Way’s conceptualization of the playing field: the partly lacking conceptual logic. The other issues are untested causal relationships in the conceptualization and the dichotomization of a disaggregated concept. I will deal with each in turn below.

2.1 Conceptual logic: redundancy Footnote 3

While the initial discussion of the attributes of the playing field seems to indicate that access to law refers to the relative neutrality of nominally independent dispute resolution institutions (Levitsky and Way 2010a, pp. 10–12), this is not reflected in Levitsky and Way’s operationalization, where the indicator focuses on the politicization of state institutions in general (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 368). This creates a discrepancy between conceptualization and operationalization, making it difficult to know what Levitsky and Way really mean by access to the law. At the component/indicator level, Levitsky and Way state that access is uneven if “state institutions are widely politicised and deployed frequently by the incumbent” (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 368). This overlaps with both the indicators for resources and of media, as these are also fundamentally about incumbent abuse of public institutions to garner advantages in terms of funding or attention. It is thus an example of redundancy: Access to law as defined by Levitsky and Way relates to the same issues of the overarching concept as the two other attributes within the concept (Munck and Verkuilen 2002, p. 13). The consequence is that there should be no instances that violate the criteria for access to resources or media but not access to the law. Yet Levitsky and Way identify several such instances, notably Benin, Botswana and Madagascar between 1990 and 1995, and Botswana in 2008 (Levitsky and Way 2010a, pp. 369–371). As the attribute is operationalized, it does not serve a clear purpose. Had the operationalization been more connected to supposedly neutral arbiters and their conduct, access to law would be clearly distinguishable from the other attributes.

2.2 Untested causal relationships: agency, cause and effect

As noted by Goertz (2006, pp. 54–55), the fact that causal relationships are often central components of concepts can potentially be problematic and they should therefore be both explicitly stated, theoretically well-founded and, if possible, empirically tested. Levitsky and Way include two causal relationships in their definition of the playing field. First, they state that the playing field is “uneven” if and only if “incumbent abuse of the state” generates disparities (Levitsky and Way 2010b, p. 57, emphasis added). Here they argue that for the playing field to be uneven, any disparities between incumbent and elite must be a result of incumbent agency: The incumbent must intentionally manipulate access to resources, media or the law. However, must unfair disparities always be the result of incumbent abuse? And how do we separate “abuse” from use? These questions should be addressed in greater detail.

I argue that while intent to abuse might be present in most cases, this is not necessarily so. The issue of patronage highlights this. According to Levitsky and Way’s analysis, patronage-based machines were one of the most important aspects of the uneven playing field in many competitive authoritarian regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa (Levitsky and Way 2010a, Chap. 6). However, if the patronage networks were created as a side effect of policies intended to do otherwise—for example policies aimed at boosting employment—they would not qualify as contributing to an uneven playing field according to Levitsky and Way’s definition. Botswana is a case in point. While the state-owned Debswana company’s monopoly in the diamond industry undoubtedly contributed to an uneven playing field as illustrated by Levitsky and Way (2010a, pp. 255–256), it is hard to prove that the intent of establishing and running such a monopoly was and is to prevent the opposition from effectively mobilizing. The question of agency and intentionality should therefore be analysed and measured to the greatest extent possible, but not necessarily included in the definition and operationalization.

The second causal relationship mentioned and included in the definition is that the playing field is only uneven if the disparities created by incumbent abuse impede the opposition’s ability to organize and compete (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 368). As it stands, Levitsky and Way’s framework is not primarily intended for the purpose of understanding the playing field. Instead it is primarily used for operationalizing a cut-off point between different regime types based on precisely this point. However, while there might be merit to Levitsky and Way’s causal claim, this should not in any way rule out a more thorough focus on and measurement of the playing field before investigating its relative impact. If, as Levitsky and Way argue, an uneven playing field is an increasingly important “tool” for autocrats (Levitsky and Way 2010b, p. 57), then it is imperative to investigate the issues involved separately from their origin and especially their impact. Furthermore, it is important to investigate the causal claim and identify where and when the playing field prevents opposition mobilization. It is therefore necessary to separate cause and effect. Some existing studies highlight this. Opalo points out that the 2011 election in Zambia led to a turnover despite “the tilt that he [incumbent President Banda] and his party … had given to the electoral playing field by misusing state resources and vastly outspending the opposition” (Opalo 2012, p. 80). Similarly, while de Jager and Meintjes (2013) find that the playing field is uneven both in Botswana and South Africa, its composition is very different, which in turn has significant effects in terms of its impact on the opposition. Cause and effect should therefore be held as separate as possible.

2.3 Dichotomization: oversimplified measurement of a complex concept

Given that Levitsky and Way are primarily interested in the impact of the playing field for categorical purposes, a dichotomous measure makes sense as it provides a clear cut-off point. However, there are important arguments for a more differentiated measurement of the evenness of the playing field. While it is true that something is either even or uneven, there are clearly different degrees of unevenness, and with events involving people there is almost never perfect evenness. Levitsky and Way themselves acknowledge this as they discuss the “slope”Footnote 4 of the playing field (Levitsky and Way 2010b, p. 64). They furthermore describe a total dominance of the playing field in the early 1990s in Zimbabwe, but after the economic downturn in the late 1990s the playing field became much more even (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 241). Nevertheless, the playing field is coded as static throughout the entire period, thus hiding temporal variation. De Jager and Meintjes (2013) find the playing field uneven in both South Africa and Botswana, but describe significant variation in this unevenness. A more discriminating and disaggregated measure would therefore allow for more variation across both time and space.

A disaggregated concept furthermore makes it possible to look at the different aspects of the playing field separately or together, depending on the purpose. This does however necessitate an open approach regarding which data is used, who does the coding and what the coding decision is based on. Thus the coding process must be transparent and open, especially as coding decisions involved in measuring an abstract concept such as the playing field will entail some sort of subjective judgement. While such judgements are not inherently unwanted and are often necessary and even productive, they necessitate a very open approach in terms of how judgements are made (Schedler 2012). While Levitsky and Way provide a list of indicators (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 368), they are extremely hard to replicate, as they are very broad. They do not provide an explicit list of coders or sources of data. Instead, they base their decisions largely on secondary literature and expert opinions, without applying any standardized framework.Footnote 5 We are thus left to wonder why Zambia violates the criteria of access to media in 2008 whereas Benin and Mali do not, despite VonDoepp and Young (2013) identifying relatively free private media that all experienced harassment in the period in all three countries.

3 A new framework studying the playing field

Following the discussion above, the playing field is defined as the balance between incumbent and opposition in access to resources, media and the law. The proposed concept is organised as a four-level framework (Goertz 2006; Munck and Verkuilen 2002), with each level (concept—attribute—component—indicator)Footnote 6 organised in a hierarchical relationship as illustrated in Table 1. The framework roughly corresponds to Levitsky and Way’s framework in two ways: (1) the overall attributes (column 1 in Table 1) discussed above, and (2) which actors that are relevant to study. Given that the playing field in this instance is related to electoral politics, it makes sense that what is relevant is the difference in access between the incumbent and opposition competing in elections.Footnote 7 While it might be slightly misleading to lump all opposition parties together, it is analytically useful as it provides a better understanding of the opportunity structure they face.

It is nevertheless important to do something that Levitsky and Way disregard as a result of their focus on the impact of the playing field: specify the different components (column 2 in Table 1) of the attributes of the playing field and clarify the respective indicators (column 3 in Table 1). The point of departure of the components of the framework is that access to resources, media or the state can come from different sources. This means that each component in the framework represents a different possible avenue of access. This focus on different sources allows for an understanding of which parts of the playing field are “closed” to the opposition, and which are open. Previous studies have highlighted that precisely the diversity of the “menu of manipulation” (Schedler 2002) and the interplay between different sources of resources is important to understand the electoral playing field between incumbent and opposition (e.g. Albaugh 2011; Arriola 2013; Lynch and Crawford 2011; Rakner and van de Walle 2009).

The indicators that the coders should use to assess the evenness in access to the different components are posed as a set of questions. This is a common way of measuring elements related to complex, composite concepts with regard to electoral quality (e.g. Bland et al. 2013; Elklit and Reynolds 2005; Norris et al. 2013). The coder should code each indicator on a scale from − 4 to + 4, where − 4 is a situation where the indicator totally favours the opposition, 0 symbolizes a relatively even opportunity for both incumbent and opposition, and + 4 is a situation where access to the indicator totally favours the incumbent. The intermediate scores of − 3, − 2, − 1, 1, 2, and 3 refers to a high, moderate and low advantage for the opposition and incumbent respectively.Footnote 8 The indicators are then averaged at the component level. For the temporal scope of each unit, the coder should focus on the situation during a full electoral cycle.Footnote 9 This means that a score should be assigned based on the situation from the point in time when a national election ends (the result is official and all complaints are settled) and until the next national electoral cycle is complete (the results of a new national election is official and all complaints settled).Footnote 10

However, the coder will not only have to assess the score of the component, but also its importance for the playing field. As highlighted by Bland et al., a common problem with measures that rely on a list of issues that should be assessed is that they often “do not provide a means of weighing the relative importance of each item on the list” (Bland et al. 2013, p. 360). Goertz (2006, p. 46) argues that the issue of weighting is especially crucial for concepts where the different attributes and components are potentially substitutable and vary across space and time, both of which I argue are true for the playing field. While adding an importance weight might seem similar to the impact criteria of Levitsky and Way, it is different because importance refers to whether and what importance the component has in the overall picture of the playing field rather than the impact it has on the competition between the incumbent and opposition. Each coder must therefore assign an “importance score” of 0 (no importance), 0.5 (low importance), 1 (medium importance), or 1.5 (high importance) based on how important the component is deemed to be for the playing field. This is a version of what Goertz (2006, p. 46) calls “weighting of necessary conditions”. The component score will then be multiplied with the importance score of that component, thus eliminating the value of any component with little or no importance and increasing the value of any component with high importance. The importance-adjusted component-scores should then be added together and standardized at the component level.Footnote 11

In the following, the components of each attribute are explained and discussed. The discussion of the framework is based on studies of electoral competition in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, I would argue that the attributes of the framework are universal in nature and can therefore serve as a point of departure for studies of the playing field from other locations as well.

3.1 Access to resources

Access to resources is extremely important in the Sub-Saharan African electoral game. Large geographic distances and poor infrastructure combined with a campaign culture of visiting as many people as possible and organising rallies demands large quantities of both material and non-material resources (Saffu 2003, pp. 21–23). On average, incumbents in Africa tend to be well funded, especially in countries where the state plays an important economic role (Butler 2010; Saffu 2003; van de Walle 2003). And with a weak private sector and relatively few instances of institutionalized public funding, opposition parties tend on average to be underresourced (Arriola 2013; Rakner and van de Walle 2009; Randall and Svåsand 2002). Five broad categories of funding sources are particularly important for political parties in the Sub-Saharan African context: internal funding, private funding, public funding, illicit public funding, and foreign funding (Bryan and Baer 2005; Butler 2010; Helle 2011; Saffu 2003).

In terms of internal and private funding, the indicators selected focus on fundraising through small-scale membership contributions as well as wealthy individuals and businesses, all of which have an effect on the Sub-Saharan African context (Bryan and Baer 2005; Butler 2010; Saffu 2003). Despite this, there is still no denying that on average the most important source of revenue for political parties in Africa is the state (Saffu 2003, Bryan and Baer 2005). If there is legal public funding of parties or party campaigns, it is still not necessarily based on fair criteria and implementation (Bryan and Baer 2005; Helle 2011). The indicators on public funding therefore focus on this. In terms of illicit public funding, either abuse of public resources such as staff and infrastructure or direct money flows form public coffers to the ruling party or elite can contribute to an uneven playing field (Helle 2011; Prempeh 2008). Finally, the diaspora, foreign governments and business interests have been found to play a significant role in funding political parties in Sub-Saharan Africa (Bryan and Baer 2005; Burnell and Gerrits 2010; Helle 2011; Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 249).

3.2 Access to media

In the last 10 years, online media and mobile technology have gradually expanded the variety of sources and availability of media in Sub-Saharan Africa (Wasserman 2011, p. 4). However, access is contingent on social status and place of residence, creating vast differences in the importance of various media sources (Hyden and Okigbo 2002; VonDoepp and Young 2013). Three broad categories of media are important: private, public, and PSCFootnote 12 media.

Private media varies significantly in importance and outreach, but has still played a central role in electoral struggles on the continent. Like private funding, access to private media can be uneven, either as a result of ownership structures (Andriantsoa et al. 2005) or through government pressure or harassment that might induce self-censorship and biased reporting (VonDoepp and Young 2013). In terms of public media, demands should be stricter. Public media should in theory represent the interests of the citizens of the state, and provide relatively equitable coverage for all political parties competing in an election. For the playing field to be coded as even in terms of public media, the opportunities of access should be equal both in terms of quantity and quality of coverage in all relevant media platforms. With other types of media, a combination of new technological innovations and public frustration with existing media has fuelled an increasingly vibrant popular and communal media environment in many African countries that uses both new and old technology to reach out to people (Wassermann 2011). Opportunities to access and use alternative media such as communal radio stations, SMS campaigns and mobile services, as well as online and social media should therefore also be equal where relevant.

3.3 Access to law

As mentioned above, this framework focuses on the narrower notion of access to law as access to nominally independent arbiters that affect the playing field. The two prominent institutions here are electoral management bodies (EMBs) and courts. In the case of the former, these can be uneven in their direct or indirect dependence on government, or through skewed access (Bland et al. 2013; Elklit and Reynolds 2005; Lopez-Pintor 2000; Mozaffar 2002). EMBs must thus be neutral in composition, funding, and access; act on all legitimate input despite where the input originates from; and act as a neutral arbiter if conflicts arise.

In cases where the EMB is not the designed arbiter for complaints related to conduct of elections and thus the playing field, the court system usually is (Schedler and Mozaffar 2002, p. 16). Given that courts can be controlled through direct and indirect means (Ginsburg and Moustafa 2008, pp. 14–20; Gloppen et al. 2010), it is essential to develop indicators that investigate the fairness of access to the courts. All relevant parties should have equal possibilities to forward, advocate for and win their cases, and the courts should uphold their role in ensuring that the legal aspects of the playing field remain equal.

3.4 A small note on data

Given the specific nature of the indicators above, the demand on data quality is high. The framework is therefore best suited as a guide for primary data collection. A non-exhaustive list of data collection techniques and sources of data include interviews with key actors, stakeholders and experts; expert and media surveys; media publication data; party accounts; legal evaluations; and public documents and reports. Thorough primary data collection would allow for a triangulation of data to evaluate the composition of the playing field. This could potentially make the framework a valuable tool for election observation missions, political risk analysis and political economy analysis.

Using the framework to analyse the playing field by investigating secondary sources is more difficult, especially across time and space. This is because the framework asks for very specific information that may not be easily accessible. If secondary sources are used, it requires a very rigorous analysis of the variety of sources available. The coding is much more difficult because secondary sources invariably involve some form of subjective evaluation, and the differences found in access between the indicators might be as much about differences of opinion between the researchers as actual differences in access to different sources of the playing field. A triangulation exercise is therefore preferred because it is easier to code cases where plenty of information exists, and where this information is recent. Another option would be to find indicators that function as proxies for the questions posed in the framework. For example, instead of making an overall assessment of access to private media, a researcher might use social network analysis to calculate the relative closeness of media owners to the incumbent or opposition.

Although there are clear challenges in using secondary data, it is a worthwhile effort, especially as a point of reference given that Levitsky and Way base their analysis on secondary sources. Thus in the following section, the framework is applied to one of Levitsky and Way’s cases: Zambia after the MMD came to power in 1991.

4 (Re)coding Zambia under MMD rule

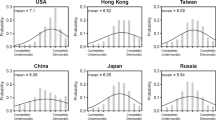

Levitsky and Way (Levitsky and Way 2010a, pp. 370–371) code the playing field in Zambia as static. It is uneven in terms of access to resources, media and the law both during the 1990–1995 period and in 2008. While acknowledging in their empirical analysis that changes did occur in access to the different aspects of the playing field (Levitsky and Way 2010a, pp. 288–291), this is not reflected in their measurement. By applying the framework presented above, a somewhat different scenario emerges. Tables 2–6 in Appendix 2 present the information, the coding decisions and the results of the coding exercise. The coding is based on a review of published literature, including Levitsky and Way’s own sources that focus on political competition in Zambia. Empirical information from country reports on Zambia from Freedom House, the US Department of State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labour, and election-monitoring reports have also been consulted.Footnote 13 They highlight clear variations over time in access to resources, media, and the law. Even at the aggregate level, there are changes for every electoral cycle with the exception of access to law from 2001 to 2006 and 2006 to 2008, and media from 2008 to 2011. The changes are described in Fig. 1. A score of 0 constitutes an even playing field, while scores above 0 can be seen as higher access for the incumbent relative to the opposition. A score of 3 would indicate that access largely favours the incumbent.

In Zambia the playing field has moved from providing the incumbent with a clear advantage in the 1996 election, to a much more even (though still unfair) contest in the post-Chiluba period from 2001 onwards. At the aggregate level the changes between electoral cycles have been relatively synchronized. However, while access to media and access to law have become increasingly even over time, access to resources has consistently favoured the incumbent to a large extent. The analysis of the Zambian case thus shows how the framework presented here offers a much more dynamic picture of the playing field than that of Levitsky and Way. It shows not only that the playing field is changing, but also which elements of the playing field are changing and at what level. While the playing field has indeed remained uneven and tilted towards the incumbent in all elections under MMD rule in Zambia, the degree of the tilt has varied considerably.

While it is not within the scope of this article to thoroughly investigate what is driving these changes, scores at the component and indicator level provide at least some clues that can form the basis for further research. Regarding access to media, it becomes clear that what changed from the 1996 election cycle onwards was not that access to public media became significantly more even, but that there were simply other alternative media channels for the opposition to access and that these became gradually more important. First the presence of private newspapers and community radio stations, and later private broadcasters and new media, made the continued bias of public broadcasters less significant. Thus, while Moyo (2010) might be right in labelling the MMD government “reluctant liberalizers”, the fact that several private media outlets with significant outreach did emerge out of the liberalization process in Zambia (Willems 2013, p. 225), has contributed to a more even playing field. While some private outlets, notably The Post newspaper after 2006, were biased towards the opposition, most provided relatively balanced political coverage, demonstrating the positive role of neutral media outlets in balancing the playing field.

Access to law slowed over time, as the supposedly “neutral arbiters” (the EMB and the courts) became more substantively neutral. There are several potential reasons for this: increasing professionalization and capacity, a more benevolent incumbent, or that the level of electoral malpractice has decreased over time. These explanations nevertheless support Lindberg’s (2009) hypothesis of the democratizing effect of elections over time, as institutions and actors gradually adopt more democratic practices through repetitious processes.Footnote 14

As Fig. 1 shows, access to resources is the attribute of the playing field that remained tilted against the opposition throughout MMD rule. Even in the 2011 elections won by the opposition, the MMD had a massive resource advantage, largely as a result of its creative use of state resources (EUEOM 2011, p. 14). As Pitcher (Pitcher 2012, p. 118) highlights, the MMD abused state resources both for in-campaign and between-campaign purposes throughout its tenure. The lack of access to state funding for other parties meant that opposition parties had to rely on wealthy private individuals in order to compete with the financial muscle of the MMD. While available private sector funding never balanced the playing field, the presence of at least some independent private funding, both as a result of liberalization processes and wealthy individuals defecting from the ruling party in the 1990s, meant that the MMD did not succeed in closing access to resources completely (Pitcher 2012, pp. 116–125). This contrasts with Mozambique or Uganda, where the ruling regimes have been able to successfully control funding from private businesses as well as private media to a much larger extent (Helle 2011; Pitcher 2012). Again, this highlights the importance of understanding different sources of access to different aspects of the playing field.

These discussions show the merit of disaggregating a complex concept such as the playing field to understand not only what drives changes in the playing field at the aggregate level but also what drives the changes in its respective attributes. It is especially important given that the underlying causes of changes in the playing field might vary significantly between its different components.

The point about access to resources also highlights why it is so important to separate the playing field as a concept from the impact it has on the opposition. As Hess and Aidoo (Hess and Aidoo 2013, p. 138) have recently argued, in the 2011 elections the Patriotic Front (PF) actually managed to turn the resource advantage of the MMD into an electoral advantage, as the opposition could claim that the government was bought by foreign (mostly Chinese) interests and therefore did not have the best interests of Zambians in mind. Party Leader Michael Sata and the PF also actively encouraged voters to accept bribes offered by the MMD but to vote for the PF instead, as it would put more money in voters’ pockets after the elections instead of offering government hand-outs in advance (Helle and Rakner 2012, pp. 10–11). While the abuse of state money clearly made access to resources uneven, the impact it had on the opposition was at the same time partly positive. This was, however, contingent on an intermediate factor: the tactics chosen by the opposition.

This leads to a final note regarding the mapping of the playing field in Zambia: The MMD did not lose power at the point in time when the playing field was most even. Though the differences were not large, the 2006 elections were in many ways fairer than the 2011 elections. However, while Levy Mwanawasa and the MMD won the election in 2006, Rupiah Banda lost in 2011. This corroborates the finding above that the impact of the playing field on not just the opposition but also the outcome of elections is contingent on or subservient to a number of other factors. Opposition parties can and do win when the playing field is uneven, as long as it is able to adapt to the circumstances. As highlighted by Schedler (Schedler 2013, pp. 369–370), the response of the opposition to the uneven playing field might be just as critical for understanding eventual regime change as underlying structural variables and the state of the playing field. It is therefore essential to see the nature of the playing field as simply one of many variables that affect the opposition’s ability to mobilize and compete.

5 Studying the playing field: a way forward

The case of Zambia thus highlights three important issues regarding the concept of the playing field. First, the playing field should not be seen as static, as the level of unevenness shifts significantly between electoral cycles. Second, a disaggregated approach to measuring the playing field highlights that there may be different underlying drivers and mechanisms of change involved in the different attributes of the playing field. Third, the slope of the playing field is not necessarily a suitable indicator of the impact it has on the opposition or election outcomes.

The framework put forth and discussed in this paper thus presents a very different reality to the static presentation of the playing field in Zambia made by Levitsky and Way. It highlights the deficiencies of Levitsky and Way’s definition and measurement, particularly with respect to the static nature of their measure and their failure to separate the playing field from its impact on the opposition. While the creation of a dichotomous measurement might have been necessary for Levitsky and Way’s purpose, it might not serve as the best tool for understanding the playing field. Studies of the playing field or its attributes should thus use caution when applying Levitsky and Way’s framework.

If the primary purpose of future studies is to understand the playing field itself, the framework presented here can provide a point of departure. It opens several new interesting avenues of research. First, efforts should be made to use this framework to investigate the causal claims inherent in Levitsky and Way’s definition. How important is agency for the emergence or preservation of an uneven playing field? When does an uneven playing field prevent the opposition from mobilizing effectively? Second, further effort needs to focus on how different attributes of the concept act separately and collaboratively. Are the same underlying conditions driving changes in all attributes? Are some combinations of an uneven playing field more unfavourable for fair competition than others? Finally, efforts need to be focused on solving the “big” question: What drives changes in the overall playing field? How can we achieve true “contestability” (Bartolini 1999, p. 457) in a political system? And what level of fairness is fair enough? These are all questions that future applications of this framework should aim to address.

Notes

Levitsky and Way alternate between referring to this attribute as “access to state institutions” (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 368, 2010b, p. 57) and “access to the law” (Levitsky and Way 2010a, p. 12, 2010b, p. 60). This is linked to a discrepancy between conceptualization and measurement (see discussion below).

There are some who would disagree, however. In a recent analysis of the playing field in South Africa and Botswana, de Jager and Meintjes (de Jager and Meintjes 2013, p. 249) argue that Levitsky and Way’s categories are not comprehensive enough, as the difference in the playing field between these two countries is fundamentally about the African National Congress’s (ANC) liberation credentials in the South African case. What de Jager and Meintjes fail to specify, however, is whether the liberation credentials are an unfair advantage in and of themselves, or if it is the potential consequences (such as increased access to public finances) of the liberation credentials that could create an uneven playing field. This highlights the importance of separating the causes and effects of the playing field from the measurement of the concept, and underscores the importance of it being as minimalist as possible for the concept to have any analytical purpose (for a similar argument on measures of democracy, see Munck and Verkuilen 2002, p. 9).

At the level of conceptualization where Levitsky and Way link the playing field to the issue of regime identification, they are guilty of another breach of conceptual logic as they have the playing field as a separate component at the same level as civil liberties, and free and fair elections and as a subcomponent of free and fair elections (l.evitsky and Way 2010a, pp. 366–368). This is an example of conflation (Munck and Verkuilen 2002, p. 13), which is a potentially serious problem not just in a logical but also in an empirical sense. However, since this article is primarily concerned with the playing field as a concept and not how the playing field is linked to the issue of regime, the issue will not be pursued further in this article.

Levitsky and Way use the term “slope”. To avoid confusion, this framework prefers to use “degrees” to highlight the categorical nature of the framework.

The author has contacted Levitsky and Way to ask them about whether they kept any additional records of coding guides and/or overview of sources consulted, but their answer was that the information provided in the book (2010a) is what was used. See Bardall (2015) in this volume for a similar critique.

In Goertz’s (Goertz 2006, p. 6) framework, the corresponding levels of the framework are called basic level, secondary level, and indicator/data level. The latter can be seen as a combination of the component and indicator level.

The framework is primarily designed to analyse electoral contests at the national level of politics. In systems with different elections for the executive and legislative, the playing field might plausibly be different in each race. In instances where it is possible to distinguish between these cases, it would be a worthwhile effort. In most cases it would be difficult to separate them though. While the framework is designed to analyse contests at the national level, most of the concepts and indicators could also serve as a point of departure for analysing the playing field in sub-national contests.

See Appendix 1 for more thorough instructions on coding, or contact author directly for more exhaustive information.

In situations where executive and legislative elections are not held simultaneously, efforts should be made to measure the playing field separately.

In terms of founding elections, the starting point of the electoral cycle will have to be decided on an individual basis.

The components that are deemed as not important will be left out of the standardization exercise, as they should have no effect on the playing field.

PSC refers to popular, social, and communal media.

See the end of Appendix 2 for a full list of literature reviewed.

However, as noted by Bogaards (2013), the evidence regarding the overall effect of elections is far more varied than Lindberg’s theory predicts.

References

Albaugh, Ericka A. 2011. An autocrat’s toolkit: Adaptation and manipulation in ‘democratic’ Cameroon. Democratization 18 (2): 388–414.

Andriantsoa, Pascal, Nancy Andriasendrarivony, Steven Haggblade, Bart Minten, Mamy Rakotojaona, Frederick Rakotovoavy, and Harivelle Sarindra Razafinimanana. 2005. Media proliferation and democratic transition in Africa: The case of Madagascar. World Development 33 (11): 1939–1957.

Arneson, Richard. 2008. Equality of opportunity. In: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2008 ed.), ed. Edward N. Zalta. http://plato.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/encyclopedia/archinfo.cgi?entry=equal-opportunity. Accessed 08 March 2014.

Arriola, Leonardo R. 2013. Capital and opposition in Africa: Coalition building in multiethnic societies. World Politics 65 (2): 233–272.

Bartolini, Stefano. 1999. Collusion, competition and democracy: Part I. Journal of Theoretical Politics 11 (4): 435–470.

Bartolini, Stefano. 2000. Collusion, competition and democracy: Part II. Journal of Theoretical Politics 12 (1): 33–65.

Bjornlund, Eric. 2004. Beyond free and fair: Monitoring elections and building democracy. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

Bland, Gary, Andrew Green, and Toby Moore. 2013. Measuring the quality of election administration. Democratization 20 (2): 358–377.

Bogaards, Matthijs. 2013. Reexamining African elections. Journal of Democracy 24 (4): 151–160.

Bryan, Shari, and Denise Baer, eds. 2005. Money in politics: A study of party financing practices in 22 countries. Washington, DC: National Democratic Instistitute for International Affairs.

Burnell, Peter, and André Gerrits. 2010. Promoting party politics in emerging democracies. Democratization 17 (6): 1065–1084.

Butler, Anthony. 2010. Introduction: Money and politics. In Paying for politics: Party funding and political change in South Africa and the global South, ed. Anthony Butler, Johannesburg: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung.

Carothers, Thomas. 2002. The end of the transition paradigm. Journal of Democracy 13 (1): 5–21.

de Jager, Nicola, and Cara H. Meintjes. 2013. Winners, losers and the playing field in Southern Africa’s ‘Democratic Darlings’: Botswana and South Africa compared. Politikon 40 (2): 233–253.

Elklit, Jørgen, and Andrew Reynolds. 2005. A framework for the systematic study of election quality. Democratization 12 (3): 147–162.

Elklit, Jørgen, and Palle Svensson. 1997. What makes elections free and fair? Journal of Democracy 8 (3): 32–46.

EUEOM. 2011. European election observation mission Zambia 2011: Final Report. Brussels: European Commission.

Gandhi, Jennifer, and Ellen Lust-Okar. 2009. Elections under authoritarianism. Annual Review of Political Science 12: 403–422.

Ginsburg, Tom., and Tamir Moustafa, eds. 2008. Rule by law: The politics of courts in authoritarian regimes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gloppen, Siri, Bruce M. Wilson, Roberto Gargarella, Elin Skaar, and Morten Kinander, eds. 2010. Courts and power in Latin America and Africa. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goertz, Gary. 2006. Social science concepts: A user’s guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Goodwin-Gill, Guy S. 1998. Codes of conduct for elections: A study prepared for the inter-parliamentary union. Geneva: Inter-parliamentary Union.

Gould, Richard, and Christine Jackson. 1995. A guide for elections observers. Darthmouth: Commonwealth Parliamentary Association.

Hadenius, Axel, and Jan Teorell. 2007. Pathways from authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy 18 (1): 143–156.

Helle, Svein-Erik. 2011. Living in a material world: Political funding in electoral authoritarian regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Thesis published for degree of Master in Comparative Politics, University of Bergen.

Helle, Svein-Erik, and Lise Rakner. 2012. The interplay between poverty and electoral authoritarianism: Poverty and political mobilization in Zambia and Uganda. CMI Working Paper 2012/3. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

Hess, Steve, and Richard Aidoo. Charting the roots of anti-chinese populism in Africa: A comparison of Zambia and Ghana. Journal of Asian and Africa Studies 49: 129–147.

Hyden, Göran, and Charles Okigbo. 2002. The media and the two waves of democracy. In Media and democracy in Africa, eds. Folu Folarin Ogundimu, Göran Hydén, and Michael Leslie, Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

Levitsky, Steven, and Lucian Way. 2002. Elections without democracy: The rise of competitive authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy 13 (2): 51–65.

Levitsky, Steven, and Lucian Way. 2010a. Competitive authoritarianism: Hybrid regimes after the Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Levitsky, Steven, and Lucian Way. 2010b. Why democracy needs a level playing field. Journal of Democracy 21 (1): 57–68.

Lindberg, Staffan. 2009. The power of elections in Africa revisited. In Democratization by elections: A new mode of transition, ed. Staffan Lindberg. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lopez-Pintor, Rafael. 2000. Electoral Management Bodies as Institutions of Governance. UNDP Discussion Papers on Governance. New York: UNDP.

Lynch, Gabrielle, and Gordon Crawford. 2011. Democratization in Africa 1990–2010: An assessment. Democratization 18 (2): 275–310.

Merloe, Patrick. 1997. Democratic elections: Human rights, public confidence and fair competition. Washington, DC: NDI.

Morgenbesser, Lee. 2013. Elections in hybrid regimes: Conceptual stretching revived. Political Studies 62 (1): 21–36.

Morse, Yonatan L. 2012. The Era of electoral authoritarianism. World Politics 64 (1): 161–198.

Moyo, Dumisani. 2010. Musical chairs and reluctant liberalization: Broadcasting policy reform trends in Zimbabwe and Zambia. In Media policy in a changing Southern Africa: Critical reflections on media reforms in the global age, eds. Dumisani Moyo, and Wallace Chuma, Pretoria: UNISA Press.

Mozaffar, Shaheen. 2002. Patterns of electoral governance in Africa’s emerging democracies. International Political Science Review 23 (1): 85–101.

Mozaffar, Shaheen, and Andreas Schedler. 2002. The comparative study of electoral governance—introduction. International Political Science Review 23 (1): 5–27.

Norris, Pippa, Richard W. Frank, and Ferran Martinez i Coma. 2013. Assesing the quality of elections. Journal of Democracy 24 (4): 124–135.

Opalo, Kennedy Ochieng. 2012. African elections: Two divergent trends. Journal of Democracy 23 (3): 80–93.

Pitcher, M. Anne. 2012. Party politics and economic reform in Africa’s democracies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Prempeh, H. Kwasi. 2008. Presidents untamed. Journal of Democracy 19 (2): 109–123.

Rakner, Lise, and Nicolas van de Walle. 2009. Opposition weakness in Africa. Journal of Democracy 20 (3): 108–121.k

Randall, Vicky, and Lars Svåsand. 2002. Political parties and democratic consolidation in Africa. Democratization 9 (3): 30–52.

Roemer, John E. 1998. Equality of opportunity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Saffu, Yaw. 2003. The funding of political parties and election campaigns in Africa. In Funding of political parties and election campaigns, eds. Reginald Austin, and Maja Tjernström, Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assitance IDEA.

Schedler, Andreas. 2002. The menu of manipulation. Journal of Democracy 13 (2): 36–50.

Schedler, Andreas, ed. 2006. Electoral authoritarianism: The dynamics of unfree competition. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Schedler, Andreas. 2012. Judgment and measurement in political science. Perspectives on Politics 10 (1): 21–36.

Schedler, Andreas. 2013. The politics of uncertainty: Sustaining and subverting electoral authoritarianism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van de Walle, Nicolas. 2003. Presidentialism and clientelism in Africa’s emerging party systems. The Journal of Modern African Studies 41 (2): 297–321.

VonDoepp, Peter and Daniel J. Young. 2013. Assaults on the fourth estate: Explaining media harassment in Africa. The Journal of Politics 75 (1): 36–51.

Wasserman, Herman. 2011. Introduction: Taking it to the streets. In Popular media, democracy and development in Africa, ed. Herman Wasserman, London: Routledge.

Willems, Wendy. 2013. Participation—in what? Radio, convergence and the corporate logic of audience input through new media in Zambia. Telematics and Informatics 30 (3): 223–231.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Lise Rakner, Jonas Linde, Matthijs Bogaards, Sebastian Elischer, the research group on democracy and development at the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen, all participants at the workshop on competitive authoritarianism in Sub-Saharan Africa at Leuphana University and two anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Directions for how to assign scores on indicators

− 4 = Indicator completely favours the opposition. Opposition has total control over access to this source.

− 3 = Indicator largely favours the opposition. Opposition has good control over access to this source, but the incumbent also enjoys negligible access.

− 2 = Indicator favours the opposition to a medium degree. Opposition has a clear edge over the incumbent in access to this source, but the incumbent also has some access.

− 1 = Indicator slightly favours the opposition. Opposition has a slight edge over the incumbent with regards to access to this source, but the difference is small.

0 = An even playing field. Either both the opposition and the incumbent have little to no access, or access is equal.

1 = Indicator slightly favours the incumbent. Incumbent has a slight edge over the opposition in access to this source, but the difference is small.

2 = Indicator favours the incumbent to a medium degree. Incumbent has a clear edge over the opposition in access to this source, but the opposition also has some access.

3 = Indicator largely favours the incumbent. Incumbent has good control over access to this source, but the opposition also enjoys negligible access.

4 = Indicator completely favours the incumbent. Incumbent has total control over access to this source.

Directions for how to assign importance scores on components

0 = No importance for the playing field. Access to component is non-existent, either as a result of the issue not existing or none of the actors using it.

0.5 = Low importance for the playing field. Access to component is of limited importance for electoral competition.

1 = Medium importance for the playing field. Access to component is important, but is not imperative for electoral competition.

1.5 = High importance for the playing field. Access to the component is critical for electoral competition.

Appendix 2: Using the framework to for measuring the playing field in Zambia under MMD-rule, 1991–2008

Component and attribute scores

Component and attribute scores

Component and attribute scores

Component and attribute scores

Component and attribute scores

Sources consulted

Publications reviewed

Baldwin, Kate. 2013. Why Vote with the Chief? Political Connections and Public Goods Provision in Zambia. American Journal of Political Science 57 (4): 794–809.

Fanda, Fackson. 1997. Elections and the press in Zambia: the case of the 1996 polls. Lusaka: Zambia Independent Media Association.

Banda, Fackson. 2006. Zambia Research findings and conclusions. African Media Development Initiative. London: BBC World Service Trust.

Bartlett, Dave. 2001. Human rights, democracy and the donors: the first MMD government in Zambia. Review of African Political Economy 28 (87): 83–91.

Bartlett, David M. C. 2000. Civil Society and Democracy: A Zambian Case Study. Journal of Southern African Studies 26 (3): 429–446.

Baylies, Carolyn and Morris Szeftel. 1997. The 1996 Zambian elections: still awaiting democratic consolidation. Review of African Political Economy 24 (71): 113–128.

Bratton, Michael. 1999. Political Participation in a New Democracy: Institutional Considerations from Zambia. Comparative Political Studies 32 (5): 549–588.

Bratton, Michael and Nicolas van de Walle. 1997. Democratic experiments in Africa: regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burnell, Peter. 1995. Building on the Past? Party Politics in Zambia’s Third Republic. Party Politics 1 (3): 397–405.

Burnell, Peter. 1997. Whither Zambia? The Zambian presidential and parliamentary elections of November 1996. Electoral Studies 16 (3): 407–416.

Burnell, Peter. 2000. The significance of the December 1998 local elections in Zambia and their aftermath. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 38, 1–20.

Burnell, Peter. 2001. Does Economic Reform Promote Democratisation? Evidence from Zambia’s Third Republic. New Political Economy 6, 191–212.

Burnell, Peter. 2001. The Party System and Party Politics in Zambia: Continuities Past, Present and Future. African Affairs 100 (399), 239–263.

Burnell, Peter. 2003. The tripartite elections in Zambia, December 2001. Electoral Studies 22, 388–395.

Carey, S. C. 2002. A Comparative Analysis of Political Parties in Kenya, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Democratization 9 (3): 53–71.

Cheeseman, Nick and Marja Hinfelaar. 2010. Parties, Platforms, and Political Mobilization: The Zambian Presidential Election of 2008. African Affairs 109 (434): 51–76.

Chirwa, Chris H. 1997. Press freedom in Zambia: a brief review of the state of the press during the MMD’s first 5 years in office. Lusaka: Zambia Independent Media Association.

Gloppen, Siri. 2003. The accountability function of the courts in Tanzania and Zambia. Democratization 10 (4): 112–136.

Gould, Jeremy. 2006. Zambia’s 2006 elections: The ethnicization of politics. Uppsala: NAI.

Hess, Steve and Richard Aidoo. Charting the Roots of Anti-Chinese Populism in Africa: A Comparison of Zambia and Ghana. Journal of Asian and Africa Studies 49: 129–147.

Ihonvbere, Julius O. 1995. From Movement to Government: The Movement for Multi-Party Democracy and the Crisis of Democratic Consolidation in Zambia. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines 29 (1): 1–25.

Ihonvbere, Julius O. 1996. Economic crisis, civil society, and democratisation: the case of Zambia. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Ishiyama, John, Anna Batta and Angela Sortor. 2013. Political parties, independents and the electoral market in sub-Saharan Africa. Party Politics 19 (5): 695–712.

Kabemba, Claude, ed. 2004. Elections and democracy in Zambia. Johannesburg: EISA.

Kasara, Kimuli. 2007. Tax Me If You Can: Ethnic Geography, Democracy, and the Taxation of Agriculture in Africa. American Political Science Review 101 (1): 159–172.

Kasoma, Francis Peter. 2002. Community radio: its management and organisation in Zambia. Lusaka: Zambia Independent Media Association.

Kiwuva, David E. 2013. Democracy and the politics of power alternation in Africa. Contemporary Politics 19 (3): 262–278.

Larmer, Miles and Alastair Fraser. 2007. Of cabbages and King Cobra: Populist politics and Zambia’s 2006 election. African Affairs 106 (425): 611–637.

Lebas, Adrienne. 2012. From protest to parties: party-building and democratization in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lindemann, Stefan. 2011. Inclusive Elite Bargains and the Dilemma of Unproductive Peace: a Zambian case study. Third World Quarterly 32 (10): 1843–1869.

Lodge, Tom, Denis Kadima and David Pottie. 2002. Compendium of elections in Southern Africa, Johannesburg: EISA.

Mason, Nicole M. and Jacob Ricker-Gilbert. 2013. Disrupting Demand for Commercial Seed: Input Subsidies in Malawi and Zambia. World Development 45: 75–91.

Momba, Jotham. 2005. Political Parties and the Quest for Democratic Consolidation in Zambia. Johannesburg: EISA.

Moyo, Dumisani. 2010. Musical chairs and reluctant liberalization: broadcasting policy reform trends in Zimbabwe and Zambia. In: Media Policy in a Changing Southern Africa: Critical Reflections on Media Reforms in the Global Age, eds. Dumisani Moyo and Wallace Chuma. Pretoria: UNISA Press

Munck, Gerardo L. and Jay Verkuilen. 2002. Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: Evaluating Alternative Indices. Comparative Political Studies 35 (1): 5–34.

Murthy, Gayatri and Muzammil M. Hussain. 2010. Mass Media in Zambia Demand-Side Measures of Access, Use and Reach. AudienceScapes Development Research Series. Washington: Intermedia.

Mwalongo, S. 2001. The role of the media in ensuring accountability in the Zambian 2001 elections. Lusaka: Zambia Institute of Mass Communications (Zamcom).

Nasong’o, Shadrack Wandala. 2007. Political Transition without Transformation. The Dialectic of Liberalization without Democratization in Kenya and Zambia. African Studies Review 50 (1): 83–107.

Opalo, Kennedy Ochieng. 2012. African Elections: Two Divergent Trends. Journal of Democracy 23 (3): 80–93.

Panter-Brick, Keith. 1994. Prospects for Democracy in Zambia. Government and Opposition 29 (2): 231–247.

Phiri, Isaac. 1999. Media in “Democratic” Zambia: Problems and Prospects. Africa Today 46 (2): 53–65.

Pitcher, M. Anne. 2012. Party politics and economic reform in Africa’s democracies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Posner, Daniel N. 2004. The Political Salience of Cultural Difference: Why Chewas and Tumbukas Are Allies in Zambia and Adversaries in Malawi. American Political Science Review 98 (4): 529–545.

Posner, Daniel N. and David J. Simon. 2002. Economic Conditions and Incumbent Support in Africa’s New Democracies: Evidence from Zambia. Comparative Political Studies 35 (3): 313–336.

Rakner, Lise. 2003. Political and economic liberalisation in Zambia 1991–2001. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute.

Rakner, Lise. 2011. Institutionalizing the pro-democracy movements: the case of Zambia’s Movement for Multiparty Democracy. Democratization 18 (5): 1106–1124.

Rakner, Lise. 2012. Foreign Aid and Democratic Consolidation in Zambia. Wider Working Paper 2012/16. Helsinki: UNU Wider.

Rakner, Lise and Lars Svåsand. 2004. From Dominant to Competitive Party System: The Zambian Experience 1991–2001. Party Politics 10, 49–68.

Rakner, Lise and Lars Svåsand. 2005. Stuck in transition: electoral processes in Zambia 1991–2001. Democratization 12 (1): 85–105.

Rakner, Lise and Lars Svåsand. 2010. In search of the impact of international support for political parties in new democracies: Malawi and Zambia compared. Democratization 17 (6): 1250–1274.

Randall, Vicky and Lars Svåsand. 2002. Political Parties and Democratic Consolidation in Africa. Democratization 9 (3): 30–52.

Resnick, Danielle. 2012. Opposition Parties and the Urban Poor in African Democracies. Comparative Political Studies 45 (11): 1351–1378.

Scarritt, James R. 2006. The strategic choice of multiethnic parties in Zambia’s dominant and personalist party system. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 44 (2): 234–256.

Simon, David. 2002. Can Democracy Consolidate in Africa amidst Poverty? Economic Influences upon Political Participation in Zambia. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 40 (1): 23–42.

Simutanyi, Neo. 2013. Zambia: Democracy and Political Participation: A review by AfriMAP and the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa. Open Society Foundation Discussion Paper. Johannesburg: Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa.

Taylor, Scott D. 2012. Influence without Organizations: State-Business Relations and Their Impact on Business Environments in Contemporary Africa. Business and Politics 14 (1).

Tordoff, William and Young, Ralph. 2005. Electoral Politics in Africa: The Experience of Zambia and Zimbabwe. Government and Opposition 40 (3): 403–423.

van Donge, Jan Kees. 2008. The EU Observer Mission to the Zambian Elections 2001: The Politics of Election Monitoring as the Construction of Narratives. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 46 (3): 296–317.

van Donge, Jan Kees. 2009. The plundering of Zambian resources by Frederick Chiluba and his friends: A case study of the interaction between national politics and the international drive towards good governance. African Affairs 108 (430): 69–90.

van Donge, Jan Kees. 2010. The 2008 presidential by-election in Zambia. Electoral Studies 29 (3): 521–523.

von Soest, Christian. 2013. Persistent systemic corruption: why democratisation and economic liberalisation have failed to undo an old evil. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 7 (1): 57–87.

von Soest, Christian, Karsten Bechle and Nina Korte. 2011. How Neopatrimonialism Affects Tax Administration: a comparative study of three world regions. Third World Quarterly 32 (7): 1307–1329.

VonDoepp, Peter. 2005. The Problem of Judicial Control in Africa’s Neopatrimonial Democracies: Malawi and Zambia. Political Science Quarterly 120 (2): 275–301.

VonDoepp, Peter. 2006. Politics and Judicial Assertiveness in Emerging Democracies: High Court Behavior in Malawi and Zambia. Political Research Quarterly 59 (3): 389–399.

Willems, Wendy. 2013. Participation—in what? Radio, convergence and the corporate logic of audience input through new media in Zambia. Telematics and Informatics 30 (3): 223–231.

Reports and other publications

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (BDHRL). 1999–2012. Human Rights Reports Zambia. Washington: U.S. Department of State.

Carter Centre. 2002. Observing the 2001 Zambian Elections. Atlanta: The Carter Centre.

Commonwealth Observer Group (COG). 2006. Zambia Presidential, Parliamentary and Local Government Elections 28 September 2006. London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

Commonwealth Observer Group (COG). 2011. Zambia General Elections 20 September 2011. London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

EISA. 2010. EISA Election Observer Mission Report: Zambia Presidential By-Election 30 October 2008. Johannesburg: EISA.

EUEOM. 2006. European Election Observation Mission Zambia 2006: Final Report. Brussels: European Commission.

EUEOM. 2011. European Election Observation Mission Zambia 2011: Final Report. Brussels: European Commission.

Freedom House (FH). 1999–2012. Freedom in the world: Country Report Zambia. Washington: Freedom House.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Helle, SE. Defining the playing field. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 10 (Suppl 1), 47–78 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-015-0264-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-015-0264-7