Abstract

Tandem cycling enables visually impaired athletes to compete in cycling in the Paralympics. Tandem aerodynamics can be analysed by track measurements, wind-tunnel experiments and numerical simulations with computational fluid dynamics (CFD). However, the proximity of the pilot (front) and the stoker (rear) and the associated strong aerodynamic interactions between both athletes present substantial challenges for CFD simulations, the results of which can be very sensitive to computational parameters such as grid topology and turbulence model. To the best of our knowledge, this paper presents the first CFD and wind-tunnel investigation on tandem cycling aerodynamics. The study analyses the influence of the CFD grid topology and the turbulence model on the aerodynamic forces on pilot and stoker and compares the results with wind-tunnel measurements. It is shown that certain combinations of grid topology and turbulence model give trends that are opposite to those shown by other combinations. Indeed, some combinations provide counter-intuitive drag outcomes with the stoker experiencing a drag force up to 28% greater than the pilot. Furthermore, the application of a blockage correction for two athlete bodies in close proximity is investigated. Based on a large number of CFD simulations and validation with wind-tunnel measurements, this paper provides guidelines for the accurate CFD simulation of tandem aerodynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

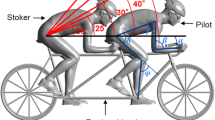

Tandem cycling is a specific discipline within para-cycling categories, with races on both the road and track (velodrome). A tandem bicycle accommodates two athletes, the pilot on the front saddle, and the stoker on the rear. Within the para-cycling community, the stoker is visually impaired, hence the necessity for a fully sighted pilot to steer the tandem at road or track race events [1]. Methods to improve an athlete’s aerodynamic profile include track ergometer measurements, wind-tunnel experiments and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations [2,3,4,5,6,7].

Computational fluid dynamics provides whole flow field data in the computational domain which can substantially increase the insight into the flow processes. Para-cycling has, to date, not seen the same knowledge investment compared to its able-bodied counterpart. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no previous analysis of para-cycling aerodynamics that utilised CFD simulations. In relation to other para-cycling disciplines, Belloli et al. [8] investigated the aerodynamics of Paralympic hand-cycling categories using wind-tunnel experiments, while the opportunities for aerodynamics enhancements with regards to prosthetics in cycling were tested by Dyer [9] on an outdoor velodrome.

The closest aerodynamic analogy to tandem cycling in the literature is the phenomenon of drafting, where two or more cyclists are in close proximity to one another. On a fundamental level, Alam [10] addressed the flow characteristics of inline configurations of two cylinders. Drag and lift coefficients were found to be highly sensitive to Reynolds number due to changes in flow structure. Íñiguez-de-la-Torre and Íñiguez [11] performed 2D CFD studies using elliptical inline shapes to represent cyclists, finding drag benefits of up to 5% for the leading cyclist. Blocken et al. [12] performed CFD simulations and a wind-tunnel test revealing for the first time that the leading cyclist experienced a drag reduction up to 2.6% for closely drafting cyclists in time-trial position. This work was expanded to four cyclists by Defraeye et al. [13] who reported that second from front and subsequent positions in a team pursuit experienced drag reductions up to 40%. Barry et al. [14] reported mean drag savings of 5%, 45%, 55% and 57% for four cyclists positioned behind each other, respectively. Barry et al. [15] also experimentally analysed the flow structures occurring in drafting. Parallels between tandem cycling and the physics of drafting can also be drawn with the work of Blocken and Toparlar [3] and Blocken et al. [4], who investigated the aerodynamic benefit for a cyclist by a trailing/following car and motorcycle, respectively, which they attributed to the subsonic upstream disturbance typical of the elliptical character of the governing Navier–Stokes equations [4]. Although drafting is the closest analogy to tandem cycling, the difference in distance between respective athletes in a tandem setup and a drafting setup is large. Drafting cyclists can have a wheel to wheel distance of 0.12 m (or less), which implies about 1.8 m between each athlete on a regular average sized racing bicycle, measured from the same point on both athletes. In comparison, the equivalent point to point distance between a pilot and stoker on a tandem bicycle is 0.8 m, which is significantly less. The close proximity of the pilot and stoker is expected to result in large aerodynamic interactions between the two athletes.

A variety of turbulence models and near-wall modelling treatments were assessed by Defraeye et al. [16] for their impact on computed cyclist drag and compared with wind-tunnel experiments. Several steady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) turbulence models as well as Large Eddy Simulations (LES) were compared with the experimental data. The shear stress transport (SST) k-omega turbulence model [17] provided the best overall agreement with the experimentally obtained drag (4% difference). Moreover, studies focusing on cycling and automotive aerodynamic interactions found good agreement between experimental data and CFD simulations [3, 4] when using the standard k-ε turbulence model [18] with scalable wall functions [19] to resolve the near-wall flow.

This paper provides new guidelines for CFD simulations for tandem cycling aerodynamics, with specific attention to near-wall grid resolution and turbulence model choice. The application of a wind-tunnel solid blockage correction to tandem athletes is explored. Furthermore, the forces experienced by pilot and stoker are investigated separately to provide an understanding of the drag interaction between the pilot and stoker athletes.

2 CFD simulations—initial findings

2.1 Computational parameters

2.1.1 Tandem geometry and computational domain

The tandem cycling setup considered in this study was selected to resemble a road race scenario. Standard road helmets as opposed to more aerodynamic time-trial (TT) helmets were used and simplified spoked wheels were fitted to the tandem bicycle opposed to disk or trispoke wheels. For the purposes of this study, the bicycle geometry was simplified by neglecting the chain, sprocket, derailleur, brake mechanisms and cables. The wheel spokes were also simplified, with twelve spokes of 0.012 m diameter modelled for front and rear wheel. An Eva [20] structured light 3D scanner provided high resolution 3D models of an athlete and a helmet (Bontrager Ballista). The same athlete geometry was used for pilot and for stoker to provide good comparability without inferring drag bias towards either pilot or stoker. The athlete was scanned in an aggressive dropped posture typically used by both tandem athletes in road races. The full-scale model for the CFD simulations had a frontal area of 0.399 m2.

A 80 × 28 × 28 m3 cuboid was used for the computational domain (Fig. 1) with the tandem geometry at 28 m from the inlet. The domain size resulted in a blockage ratio of 0.06%, below the 3% recommendation [21,22,23, 25]. Therefore blockage corrections were not required. A gap of 0.025 m between wheel bottom and ground surface was used to avoid skewed and low-quality computational cells.

2.1.2 Computational grid

The grid resolution is assessed based on the dimensionless wall unit y*:

where \(u^{*}\) is the friction velocity (Eq. 2), \(y_{\text{P}}\) is the normal distance of the cell centre point P from the wall surface, \(v\) is the local kinematic viscosity.

where \(C_{\mu }\) = 0.09, and \(k_{\text{P}}\) the turbulent kinetic energy at P.

The grids generated in this study were based on [21,22,23,24]. Two different grid topologies were devised; (i) a tetrahedral-only grid and (ii) a combined prismatic-tetrahedral grid, with prismatic cells in the boundary layers and tetrahedral cells beyond.

A grid-sensitivity study, comprising of a coarse, medium and fine tetrahedral-only grid, was conducted, with the surface grid systematically refined with each face size halved for the progressive grids. The boundary layer resolution depended on the tetrahedral cell size at the surfaces of interest for each grid as no prism layers were used. The grid sizes were 11.1, 24.6 and 64.9 million cells, respectively. The medium grid was selected as a reference grid for surface face sizings for subsequent grids, providing a compromise between accuracy and computational expense. Cell face sizes varied depending on the location of the surface on the athlete or bicycle geometry. All facet edge length (m) dimensions are provided in Table 1. The dimensions are normalised by the diameter of the athlete’s head (0.2 m). A new grid was created, denoted as grid 1, which stemmed from the medium grid in the grid independence study. Figure 2a, c illustrate segments of the surface grid, and also the volume grid in a vertical centreplane. The total number of cells in grid 1 was 20.2 million.

a Surface grid on the tandem geometry and part of the volume grid surrounding the tandem geometry (grid 2–33.3 million cells), b surface and volume grid of tandem geometry (grid 2–33.3 million cells), c tetrahedral cell growth from the surface grid on the face of the pilot (grid 1–20.2 million cells), d prism layer growth from the surface grid on the face of the pilot (grid 2–33.3 million cells)

For the second grid used in this study, denoted as grid 2, settings for grid 1 were implemented as the background grid with the addition of prism cells to all wall surfaces in the boundary layers, as advised by Tominaga et al. [21], Tucker and Mosquera [24], and Blocken [25]. This yielded a y P of 17.5 µm, an average y* of 0.80 and a max y* of 2.75. Note that y* ≈ 1 and < 5 is required to resolve the thin viscous sublayers to reproduce boundary layer flow and potential separation. The near-wall prism layers are illustrated in Fig. 2d. 20 prism cells with a growth ratio of 1.2 were used. This combined prismatic-tetrahedral volume grid is denoted as grid 2 (Fig. 2b, d). The total number of cells in grid 2 was 33.3 million.

2.1.3 Boundary conditions

A uniform velocity of 15 m/s with 0.2% turbulence intensity and a hydraulic diameter of 1 m was applied as a velocity inlet condition. Air with a density of 1.225 kg/m3 and a viscosity of 1.789e−5 kg/m s was specified as the fluid. Zero static gauge pressure was applied to the outlet boundary. A symmetry condition was applied for the lateral boundaries, the top boundary, and also for the ground boundary to represent a free-slip wall. A no-slip wall with zero roughness was applied for the tandem bicycle surfaces and for the athlete surfaces.

2.1.4 Governing equations and solver settings

The simulations were performed using ANSYS Fluent 16 [26]. The RANS equations were solved with the shear stress transport (SST) k-ω turbulence model [17]. The Least Squares Cell Based method was used to compute gradients [26]. The Coupled algorithm was used for pressure–velocity coupling. Second-order pressure interpolation was used, along with second-order discretisation schemes for all equations. Due to the inherent unsteady nature of tandem cycling aerodynamics, the pseudo-transient solver within Fluent was used. Averaging was required for the resulting forces from the pseudo-transient simulations where steady-state convergence was unachievable. A study was conducted to determine a suitable pseudo-transient time-step, with values decreasing by one order of magnitude from 0.1 to 1e−05 s. Drag values were averaged over 4500 iterations after an oscillatory phase was reached. A negligible difference was found varying time-step size, with a final size of 0.01 s used to allow for sufficient oscillations to occur over 2000 iterations for averaging purposes. All simulations reported were averaged over 2000 iterations after results reached a statistically steady state.

2.2 Drag findings

The drag coefficient is described by:

where \(F_{\text{D}}\) is the drag force (N), \(\rho\) the density (kg/m3), A the frontal area (m2) and V the velocity (m/s).

The total drag force of bicycle and two riders for grid 1 and grid 2 were 39.6 and 43.2 N, respectively (C D of 0.718 and 0.787). It was expected that the stoker would experience a lower drag than the pilot due to drafting. However, Fig. 3 shows that grid 1 yielded an opposite drag distribution: 35.9% of total drag for the pilot and 46.1% for the stoker. Grid 2 however, yielded 52.5% of total drag for the pilot and 26.9% for the stoker.

Drag force (N) on the pilot and stoker using different grids. The details of grid 1 (tetrahedral-only) and grid 2 (tetrahedral-prismatic) are discussed in Sect. 2.1.2

Figure 4 shows the differences in surface pressure coefficient, normalised wall shear stress, and the sum of both these quantities for grids 1 and 2. It is clear that the grid resolution in the boundary layer and its impact on the flow separation locations and resulting wake flow played a critical role in the drag differences between both grids. This is also shown by Fig. 5. While the over-pressure on the stoker by grid 1 (Fig. 5a) suggests that the pilot and stoker were acting as independent bodies, the pressure coefficient by grid 2 seemed to suggest that they rather acted as a single body. Two cylinders in tandem were also found to act as a single body when in close proximity [10, 27]. The friction drag was found to contribute only 8.2% and 5.7% to the total drag experienced by the pilot and the stoker respectively for grid 1, and 3.4% and 5.6% for grid 2. The primary difference in the drag forces was in pressure drag, caused by differences in the pressure recovery predictions due to the difference in flow separation locations between grid 1 and grid 2, rather than the magnitude of the friction drag predictions. Note that the athletes experienced a larger viscous drag for grid 1 due to the flow staying attached for longer to the surfaces of the athletes. Figure 5b depicts the flow staying attached to the back of the pilot and traversing around the saddle for grid 1, travelling in the opposite direction to the flow in grid 2 at the same location. To further elucidate the opposing results regarding the pilot and stoker’s drag forces for two different grids, wind-tunnel experiments and CFD simulations with different grid topologies and turbulence models were performed.

Comparison between grid 1 and grid 2 for a surface pressure coefficient, b normalised shear stress, and c sum of the surface pressure coefficient and normalised wall shear stress. C P is the surface pressure coefficient, \(\tau_{\text{w}}\) is the wall shear stress, \(\rho\) is the density and V is the reference velocity

3 Wind-tunnel experiments

3.1 Experimental setup

The wind-tunnel experiment was performed at the University of Liège, Belgium. The test chamber had a cross sectional area of 2 × 1.5 m2. A sharp edged horizontal platform was elevated by 0.3 m from the test section floor to separate the test geometries from the boundary layer at the tunnel floor (Fig. 6). The quarter-scale tandem geometry was divided into 4 separated components (Fig. 7a, b), and thus, the drag on the bodies of the pilot and stoker was measured separately. The handlebars remained attached to the hands of the athletes, but not to the bicycle frame. The tandem bicycle was separated in the middle to allow for it to be passed through the athletes’ legs and reattached with tight fitting sleeves. This was done to remove vibrations at the end of the tube lengths. Both athletes had filleted cuboid supports connecting their feet to individual baseplates, labelled in Fig. 7b as athlete supports. Both the front and rear bicycle frame and wheel components received additional supports to remove vibrations from the smaller components present. No visible vibrations occurred during testing. The largest supports are labelled as bicycle support in Fig. 7b. The front forks were simplified to a single cylindrical tube of equal diameter to the head tube. Additional changes implemented to the tandem geometries for the wind-tunnel experiments included the removal of pedals, cranks and seat tubes to separate the athlete geometries from that of the tandem bicycle. The athletes and bicycle geometries were manufactured to ¼ scale (Fig. 7c), with the support structures and baseplates included in the geometrical models. This allowed for the athlete geometries to be directly connected to the force sensors without any intermediate connection component. The blockage ratio for the setup including plate and supporting structure was 2.2%. 3D solid blockage corrections by Barlow et al. [28] were applied, which are applicable in the blockage ratio range of 1–10% [28]. A body shape value ‘K’ of 0.96 was used to approximate the shape of the tandem. A flow velocity of 60 m/s was used to match the Reynolds number of the quarter-scale tests with that of full-scale tandem cyclists at 15 m/s.

Simplified diagram of the wind-tunnel setup, adapted from Blocken et al. [4], utilising the same wind-tunnel facilities and platform. All dimensions are in mm. X, Y and Z directions indicated are positive force readout directions from both force sensors

Both athletes were individually attached to separate force transducers, for separate and simultaneous readouts during the experiment. Force was sampled at 10 Hz for 180 s during the experiment. A maximum error of 1.24 N at a 95% confidence interval was provided by the manufacturers for both force transducers. This error included systematic and random errors, the former of which was removed via biasing the transducers prior to imparting a wind load. Air velocity (x direction, Fig. 6) was recorded inside the wind-tunnel using a pitot tube. Air temperature was also recorded to correct drag measurements to an air density at 15 °C, for comparison with the CFD simulations, where an air density of 1.225 kg/m3 was used. The approach-flow longitudinal turbulence intensity was 0.2% [4].

3.2 Experimental results

The experiments showed that the stoker experienced 39% less drag than the pilot (15.55 and 25.52 N respectively), in addition to lower lift and lateral forces (Fig. 8). The stoker experienced a lateral force negative to the axis direction, which pushed the athlete to his right, while the pilot was pushed to his left. Both the pilot and stoker experienced a positive lift force of 34% and 44% of the drag forces experienced by the pilot and stoker respectively. The counter-intuitive drag findings in Sect. 2.2 using grid 1 (Sect. 2.1.2) were incorrect, where the stoker experienced a drag force 40% greater than the pilot. However, grid 2 did provide the correct trend in drag forces of both athletes (Sect. 2.2).

Wind-tunnel drag, lateral and lift force results on both the pilot and stoker geometries, with error bars ± 1.24 N for systematic and random errors. The drag values are depicted as negative as per the orientation of the force transducers (Fig. 7)

4 Impact of grid resolution and turbulence model on tandem drag

4.1 Computational settings

For CFD validation, new digital geometries were made representative of those in the wind-tunnel experiment (Fig. 7b), with foot supports, wheel supports and baseplate geometries included. Note that the CFD geometry was made at full-scale. The new frontal area of the tandem bicycle and athlete’s wind-tunnel geometry with supports included was 0.455 m2 at full-scale (0.028 m2 at quarter-scale). The drag on the handlebars, supports and baseplates connected to the athletes was included in the drag summations for the pilot and stoker, while the drag on the tandem bicycle was not considered.

A new grid sensitivity study consisting of a coarse, medium and fine tetrahedral-only grid, was conducted on the new geometrical model using the face sizes on athletes and bicycle surfaces as described in Sect. 2.1.2. The medium grid was chosen to provide the sizing for a tetrahedral-prismatic grid with prism layers identical to those described in grid 2, Sect. 2.1.2. This tetrahedral-prismatic grid, denoted as grid 3a, contained 38.2 million control volumes. A no-slip wall boundary condition was applied to the baseplate and support surfaces. A free-slip wall was applied to the ground surfaces surrounding the geometrical model. The SST k-ω turbulence model [17] was used for this study, with all solver parameters kept the same as in Sect. 2.1.4. With this starting point, the impact of near-wall grid resolution (y*) and turbulence model was investigated.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Impact of near-wall grid resolution (y*)

Seven additional tetrahedral-prismatic grids were created, representative of grid 3a (Sect. 4.1). However the y P was doubled for each grid, yielding grids b–h (Fig. 9). The y* values reported in this section relate to the surfaces of pilot and stoker geometries attached to the force sensors (Fig. 6). Figure 9 illustrates the y* distribution for grid 3a, which had a y P of 0.0175 mm, resulting in an average y* of 0.80, and a maximum y* of 2.75. An additional tetrahedral-only grid was created with no prism layers growing from wall surfaces, using the grid parameters described for grid 1 (Sect. 2.1.2). This grid is denoted as grid 3i. The average y* of grid 3i was 57.09, with a maximum y* of 240 due to the variance in y P resulting from the range of face sizes. For comparison, grid 3g obtained an average y* value of 58.15 using prism cells, but a maximum y* value of only 119 was obtained.

A comparison of drag force (N) on the pilot and stoker including baseplates, supports and handlebars across computational grids with varying average y* values. Note that for the tetrahedral grid, the max y P is provided, where a variety of smaller y P values are present due to the dependency of y P on the tetrahedral cell size

Figure 10 presents the drag forces for each grid. Note that drag forces on baseplates, supports and handlebars were included in the CFD outputs for comparison to the wind-tunnel data. As the average y* increased from 0.80 to 108.80, the pilot experienced a reducing drag force while the stoker experienced an increasing drag force. The stoker experienced a larger drag than the pilot at an average y* of 108.80, when using prism layers at wall surfaces (grid 3h). However, when using tetrahedral cells to resolve the wall bounded flow (grid 3i), this effect was magnified, resulting in the stoker experiencing a drag force 29.4% larger than the pilot. It was observed that separation was delayed or prevented by low boundary layer resolution modelling, causing the disparities between drag forces for high resolution and low resolution grids, as per Fig. 5.

To determine if the near-wall grid resolution of grid 3a was suitable for transitional turbulence models, an additional grid (grid 3j) was created based on the same geometrical geometry with a y P of 0.0025 mm, a growth ratio of 1.15, and 36 prism layers; which yielded an average and maximum y* of 0.10 and 0.89 respectively. The 4-equation transitional SST (T-SST) k-ω [29] turbulence model was tested with both grids. A 0.4% and 2.5% difference was found between grid 3a and grid 3j for drag on the pilot and stoker respectively, which was determined as too small to warrant the additional computational expense of utilising grid 3j. Thus, grid 3a was chosen for a turbulence model sensitivity analysis in Sect. 4.2.2.

4.2.2 Impact of turbulence model

Eight turbulence models were applied to grid 3a: the T-SST k-ω [29], the k-kl-ω [30], the intermittency SST k-ω [29], the SST k-ω [17], the standard k-ε [18], the realizable k-ε [31], the renormalization-group (RNG) k-ε [32], and the 1-equation Spalart–Allmaras turbulence model [34]. The 1-equation Wolfshtein model [33] was used for low Reynolds number modelling with the k-ε models. Second-order discretisation schemes were used for the convective and viscous terms of all equations. The results are summarised in Fig. 11 and Table 2. The T-SST model provided drag predictions for the pilot and stoker that deviated by − 1.0% and − 14.4%, respectively, from the wind-tunnel results. The T-SST model also failed to predict the correct direction of the lateral force on the pilot. The intermittency SST k-ω model provided comparable results to the T-SST model, with drag deviations of 2.4% and − 13.5% for the pilot and stoker respectively. The k-kl-ω model under-predicted drag for the pilot by − 14.1%, and over-predicted drag on the stoker by 4.6%. However, it predicted all lateral and lift forces to within the error region of the force transducers for both the pilot and stoker. The SST k-ω models predicted the drag of the pilot and stoker to within − 3.7% and − 13.9% of the wind-tunnel values respectively, and the Spalart–Allmaras model predicted the drag of the pilot and stoker to within − 4.0% and − 15.9% respectively. The k-ε models all under-predicted pilot drag forces beyond 30%, with the realizable and standard k-ε models predicting a larger drag force on the stoker than on the pilot.

4.2.3 Blockage effects

The blockage corrections by Barlow et al. [28] applied to the wind-tunnel data, were designed for a single bluff body, not two inline bodies in close proximity as per the tandem athletes of this study. Hence, the validity of these corrections is in question for the comparison against the full-scale tandem CFD simulations in a domain much larger than that of the wind-tunnel environment. To further investigate the potential influence of blockage, a new computational domain was created, representing the actual geometry and scale of the wind-tunnel environment used for the validation studies (Fig. 12a, b). The tandem geometry was scaled to quarter-scale as per the wind-tunnel experiment (Fig. 12c) and a 60 m/s velocity was imposed at the inlet boundary. The geometry included the elevated platform, the closed container containing both force transducers and the supporting columns (Ø 0.02 m) for the elevated platform. The wind-tunnel test section was modelled as 12 m long, with the inlet boundary condition 2.3 m from the frontal edge of the platform surface. Despite the high level of geometrical detail of the wind-tunnel environment, there may have been additional blockage effects occurring in the physical wind-tunnel due to the boundary layer development on the walls of the closed-loop wind-tunnel.

A selection of turbulence models from Sect. 4.2.2 were chosen for further investigation, the 4-equation T-SST model [29], the 3-equation k-kl-ω model [30], the 2-equation SST k-ω model [17], and the 1-equation Spalart–Allmaras model [34]. The k-ε models were not used due to their previous inaccurate force predictions for the tandem athletes (Fig. 11). The tandem geometry was representative of Fig. 7b. The grid sizings for the tandem geometry were representative of grid 3a, scaled accordingly to quarter-scale. Five prism layers with a first aspect ratio of 10 were placed on the walls of the wind-tunnel and the raised platform, which were treated as smooth no-slip walls. The grid was denoted as grid 4. The total number of cells was 36.5 million. All solver parameters followed those outlined in Sects. 2.1.4 and 4.1, apart from the pseudo-transient time-step, which was scaled to 0.000625 s to account for the quarter-scale model and 60 m/s air velocity.

Figure 13 shows the shifts in drag for the pilot and stoker measurements in the new CFD domain in comparison to the results presented in Fig. 11. Previously the T-SST turbulence model under-predicted the pilot drag by − 3.0%, and the stoker drag by − 16.2%, by comparison to the wind-tunnel measurements with blockage correction applied. In the new CFD domain, the T-SST model over-predicted the pilot drag by 9.9%, and under-predicted the stoker drag by − 7.7%. The k-kl-ω turbulence model [30] experienced a more dramatic increase in total drag, with the pilot drag now over-predicted by 6.4%, and the stoker drag over-predicted by 17.7%. The SST k-ω turbulence model provided the best all-round predictions in the scaled environment, with the pilot drag over-predicted by 4.0% and the stoker drag over-predicted by 4.2%. The Spalart–Allmaras turbulence model did not provide useful drag data, under-predicting pilots drag by − 13.2%, and over-predicting the stokers drag by 12.4%. No turbulence model provided lateral force predictions for the pilot within the error range of the force transducers (±1.24 N). The k-kl-ω turbulence model predicted the lateral force on the stoker to within 2.2%, and the Spalart–Allmaras model predicted the lift force on the stoker to within 1.6%, but the poor performance of both models in all other areas rendered them ineligible for further research purposes. The SST k-ω model was thus chosen as the best performing turbulence model for tandem aerodynamics, due to its close reproduction of the wind-tunnel results for drag force (N) on the pilot and stoker, and for the lift force on the pilot (− 3.4% difference). All force data are documented in Table 3.

Drag, lateral and lift force data on a the pilot, and b the stoker geometries, from the quarter-scale CFD models simulating the wind-tunnel environment. Blockage corrections are not applied to the wind-tunnel results in both a and b. Systematic and random errors within a 95% confidence interval are represented by error bars for the wind-tunnel data. Dashed lines present the previous predictions from Fig. 11

5 Discussion

This study investigated the aerodynamic drag for tandem para-cycling athletes. The grid and turbulence model sensitivity analysis showed that a low y* grid combined with the SST k-ω turbulence model yielded the lowest drag deviation from the wind-tunnel measurements (4.0% and 4.2% for the pilot and stoker respectively). The drag coefficient for the tandem road setup without support structures was 0.787 (C D A = 0.314 m2). The pilot and the stoker contributed 52.5% and 26.9% to the total drag, respectively. Without proper selection of near-wall grid resolution and turbulence model, total drag coefficients were obtained that appeared plausible as per Sect. 2.2, but were actually the cumulative sum of errors. Counter-intuitive drag distributions where observed, with the near-wall grid resolution (Fig. 9) and/or the use of a k-ε turbulence model (Fig. 11) identified as reasons for this discrepancy. The use of k-ε turbulence models for cycling aerodynamics as reported by Blocken et al. [4], Fintelman et al. [6], Blocken and Toparlar [3], and Defraeye et al. [16], did not yield sufficiently accurate results (< 10% deviation from experiments) for a tandem system.

The standard k-ε and realizable k-ε models predicted drag coefficients for the tandem geometry used in the wind-tunnel experiment that deviated by only 5.4% and 5.0%, respectively, from the validated drag coefficient predicted when the SST k-ω turbulence model was utilised, all using the same grid. However, by comparison to wind-tunnel experiments, the drag on the pilot was under-predicted by 39.4% when using the standard k-ε turbulence model, and over-predicted by 20.8% for the stoker, resulting in the stoker experiencing a larger drag force than the pilot. The total drag force prediction for the k-ε models conceals the inaccuracy of the drag predictions on both athletes.

Figure 4 illustrated the impact of tetrahedral cells (grid 1) when used for the near-wall grid, through differences in the predictions of surface pressure coefficient and normalised shear stress between grid 1 and grid 2. As per Sect. 2.2, there was only an 8.8% difference between the total C D of the tandem system when utilising two grids with different near-wall resolutions. However, the flow fields were fundamentally different (Fig. 5), along with the drag distributions (Fig. 3) on individual athletes, with only the fine grid resolution at the wall producing a realistic result. It is recommended that a fine near-wall grid producing a y* < 1 using the SST k-ω turbulence model, is imposed for future CFD studies on tandem cycling research, to predict flow separation from both athletes.

These observations yield both consistencies and partial inconsistencies with the findings reported in the literature. The SST k-ω turbulence model was found to yield the lowest error for tandem cycling, consistent with the turbulence model sensitivity analysis conducted by Defraeye et al. [16] for solo cyclists, who determined that it provided the best overall drag, lateral and lift force predictions from a selection of RANS turbulence models. However, the standard k-ε turbulence model was also found to provide good drag predictions for a solo cyclist, two drafting able-bodied cyclists, and a cyclist followed by a car or motorcycle [3, 4, 6, 16]. This turbulence model was found to yield large errors in drag predictions for tandem cycling.

A limitation of the CFD approach followed in this study was the use of a static geometry. The models manufactured for the wind-tunnel experiments were static, and accordingly the CFD models were also simulated as static models to validate the simulations. In reality, the athlete’s legs would move to power the cranks, resulting in rotating wheels. Vortices generated from the hips and legs of athletes can have a strong effect on the drag [7]. Investigations into a dynamic tandem setup exploring the interaction between these vortices and the pilot and stoker could provide a deeper understanding of tandem aerodynamics, and present the opportunity for further optimisation with crank-rotation phase shifts between tandem athletes. Further simplifications in this study included the wall boundary conditions for the athletes which were modelled as no-slip walls with zero roughness. Athletes would have varying roughness over their surfaces in reality due to skin, hair and clothing, which could also affect aerodynamic drag.

The effects of blockage on tandem cycling in a wind-tunnel environment are not yet fully understood and require further wind-tunnel experiments and CFD simulations to fully investigate the phenomena. In the absence of such information, for CFD validation studies it is recommended to create CFD models that replicate the dimensions of the wind-tunnel, and that include a high level of geometrical detail of the test section. After validation, new CFD models should be generated with an enlarged domain to provide more accurate aerodynamics predictions without the influence of blockage. This procedure negates the need to apply blockage corrections to the force data acquired of tandem cyclists. In addition, further investigation is required to determine Reynolds number dependence/independence of the present results through experimental testing. Reynolds number independence was analysed by Defraeye et al. [16] for a half-scale model of a solo cyclist. It was found that there were limited effects above a full-scale velocity of 10 m/s, however, it must be verified if this finding is applicable for tandem cyclists through additional research.

6 Conclusions

The aerodynamics of a tandem para-cycling road race setup was simulated using CFD, and was found to have a full-scale C D of 0.787 and C D A of 0.314 m2. A grid with coarse near-wall boundary layer resolution was found to yield counter-intuitive drag distributions for individual athletes, with the stoker experiencing a higher drag than the pilot. Wind-tunnel experiments proved the counter-intuitive drag distributions to be incorrect, with the stoker experiencing 39% less drag than the pilot. In addition to this grid dependency of achieving an average y* value close to 1, the CFD simulations were also shown to have a dependency on turbulence models, with the SST k-ω turbulence model providing the most accurate drag predictions: 4.0% and 4.2% for the pilot and stoker respectively when compared against wind-tunnel validation data, and modelling the wind-tunnel geometry within the CFD fluid domain. The realizable k-ε and standard k-ε models predicted the stoker to experience a larger drag than the pilot, despite the grid meeting the requirement of an average y* value less than 1, and using low Reynolds number modelling opposed to wall functions. The RNG k-ε model under-predicted the drag on the pilot beyond 20%. It is recommended that a fine grid with an average y* value of 1 or less be used in combination with the SST k-ω turbulence model for future tandem cycling aerodynamics research.

References

UCI (2017) Cycling Regulations, Part 16 Para-Cycling, version on 01/02/2017. Union Cycliste Internationale

Blocken B (2014) 50 years of computational wind engineering: past, present and future. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn 129:69–102

Blocken B, Toparlar Y (2015) A following car influences cyclist drag: CFD simulations and wind tunnel measurements. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn 145:178–186

Blocken B, Toparlar Y, Andrianne T (2016) Aerodynamic benefit for a cyclist by a following motorcycle. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn 155:1–10

Crouch TN, Burton D, LaBry ZA, Blair KB (2017) Riding against the wind: a review of competition cycling aerodynamics. Sport Eng 20(2):81–110

Fintelman DM, Hemida H, Sterling M, Li F-X (2015) CFD simulations of the flow around a cyclist subjected to crosswinds. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn 144:31–41

Griffith MD, Crouch T, Thompson MC, Burton D, Sheridan J (2014) Computational fluid dynamics study of the effect of leg position on cyclist aerodynamic drag. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng J Fluids Eng 136:101105

Belloli M, Cheli F, Bayati I, Giappino S, Robustelli F (2014) Handbike aerodynamics: wind tunnel versus track tests. Procedia Eng 72:750–755

Dyer B (2015) The importance of aerodynamics for prosthetic limb design used by competitive cyclists with an amputation: an introduction. Prosthet Orthot Int 39(3):232–237

Alam M (2014) The aerodynamics of a cylinder submerged in the wake of another. J Fluids Struct 51:393–400

Íñiguez-de-la-Torre A, Íñiguez J (2009) Aerodynamics of a cycling team in a time trial: does the cyclist at the front benefit? Eur J Phys 30(6):1365

Blocken B, Defraeye T, Koninckx E, Carmeliet J, Hespel P (2013) CFD simulations of the aerodynamic drag of two drafting cyclists. Comput Fluids 71:435–445

Defraeye T, Blocken B, Koninckx E, Hespel P, Verboven P, Nicolai B, Carmeliet J (2013) Cyclist drag in team pursuit: influence of cyclist sequence, stature, and arm spacing. J Biomech Eng 136(1):11005

Barry N, Burton D, Sheridan J, Thompson M, Brown NAT (2015) Aerodynamic drag interactions between cyclists in a team pursuit. Sports Eng 18:93–103

Barry N, Burton D, Sheridan J, Thompson M, Brown NAT (2016) Flow field interactions between two tandem cyclists. Exp Fluids 57(12):1–14

Defraeye T, Blocken B, Koninckx E, Hespel P, Carmeliet J (2010) Computational fluid dynamics analysis of cyclist aerodynamics: performance of different turbulence-modelling and boundary-layer modelling approaches. J Biomech 43(12):2281–2287

Menter FR (1994) Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J 32(8):1598–1605

Jones WP, Launder BE (1972) The prediction of laminarization with a two-equation model of turbulence. Int J Heat Mass Transf 15(2):301–314

Grotjans H, Menter F (1998) Wall functions for general application CFD codes. In: Proceedings of the 4th computational fluid dynamics conference (ECCOMAS’98), pp 1112–1114

Artec Europe (2017) Artec Eva, 3D Scanners. https://www.artec3d.com/3d-scanner/artec-eva. Accessed: 22 May 2017

Tominaga Y, Mochida A, Yoshie R, Kataoka H, Nozu T, Yoshikawa M, Shirasawa T (2008) AIJ guidelines for practical applications of CFD to pedestrian wind environment around buildings. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn 96(10–11):1749–1761

Franke J, Hellsten A, Schlünzen H, Carissimo B (2007) Best practice guideline for the CFD simulation of flows in the urban environment. Hamburg Germany

Casey M, Wintergerste T (2000) Best Practice Guidelines. ERCOFTAC Special Interest Group on “Quality and Trust in Industrial CFD”. ERCOFTAC

Tucker P, Mosquera A (2001) NAFEMS introduction to grid and mesh generation for CFD. NAFEMS CFD Work. Group

Blocken B (2015) Computational Fluid Dynamics for urban physics: importance, scales, possibilities, limitations and ten tips and tricks towards accurate and reliable simulations. Build Environ 91:219–245

ANSYS Fluent (2015) ANSYS Fluent theory guide. Release 16.1 Documentation. ANSYS Inc

Sohankar A (2012) A numerical investigation of the flow over a pair of identical square cylinders in a tandem arrangement. Int J Numer Meth Fluids 70(10):1244–1257

Barlow JB, Rae WH, Pope A (1999) Low-speed wind tunnel testing, 3rd edn. Wiley, New York

Menter FR, Langtry RB, Likki SR, Suzen YB, Huang PG, Völker S (2004) A correlation-based transition model using local variables—part I: model formulation. J Turbomach 128(3):413–422

Walters DK, Cokljat D (2008) A three-equation eddy-viscosity model for Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes simulations of transitional flow. J Fluids Eng 130(12):121401

Shih T-H, Liou WW, Shabbir A, Yang Z, Zhu J (1995) A new k-e eddy viscosity model for high reynolds number turbulent flows. Comput Fluids 24(3):227–238

Choudhury D (1993) Introduction to the renormalization group method and turbulence modeling. Fluent Inc. Technical Memorandum TM-107

Wolfshtein M (1969) The velocity and temperature distribution in one-dimensional flow with turbulence augmentation and pressure gradient. Int J Heat Mass Transf 12:301–318

Spalart P, Allmaras S (1992) A one-equation turbulence model for aerodynamic flows. In: 30th aerospace sciences meeting and exhibit. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the College of Engineering and Informatics at the National University of Ireland, Galway. The authors acknowledge the collaboration with Paralympics Ireland, Cycling Ireland and the Sport Ireland Institute, along with the technical support team of the Department of the Built Environment at Eindhoven University of Technology: Jan Diepens, Geert-Jan Maas and Stan van Asten. The authors acknowledge the SFI/HEA Irish Centre for High-End Computing (ICHEC) for the provision of computational facilities and support, and the partnership with ANSYS Inc. Furthermore, the authors thank Corentin Cerutti from INSA Lyon for his contribution to this project in his role as a student intern. This project did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mannion, P., Toparlar, Y., Blocken, B. et al. Improving CFD prediction of drag on Paralympic tandem athletes: influence of grid resolution and turbulence model. Sports Eng 21, 123–135 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12283-017-0258-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12283-017-0258-6