Abstract

Imaging subclinical atherosclerosis holds the promise of individualized cardiovascular (CV) risk assessment. The large arsenal of noninvasive imaging techniques available today is playing an increasingly important role in the diagnosis and monitoring of subclinical atherosclerosis. However, there is a debate about the advisability of clinical screens for subclinical atherosclerosis and which modality is the most appropriate for monitoring risk and atherosclerosis progression. This article offers an overview of the traditional and emerging noninvasive imaging modalities used to detect early atherosclerosis, surveys population studies addressing the value of subclinical atherosclerosis detection, and also examines guideline recommendations for their clinical implementation. The clinical relevance of this manuscript lies in the potential of current imaging technology to improve CV risk prediction based on traditional risk factors and the present recommendations for subclinical atherosclerosis assessment. Noninvasive imaging will also help to identify individuals at high CV who would benefit from intensive prevention or therapeutic interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CACS:

-

Coronary artery calcium score

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CV:

-

Cardiovascular

- IMT:

-

Intima-media thickness

- FRS:

-

Framingham risk score

- PET:

-

Positron-emission tomography

- SPECT:

-

Single positron emission computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Foundation, B.H. (2005) European cardiovascular disease statistics.

Wilson, P. W., et al. (1998). Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation, 97(18), 1837–1847.

Sibley, C., et al. (2006). Limitations of current cardiovascular disease risk assessment strategies in women. Journal of Women's Health (2002), 15(1), 54–56.

Berry, J. D., et al. (2009). Prevalence and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in younger adults with low short-term but high lifetime estimated risk for cardiovascular disease: the coronary artery risk development in young adults study and multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation, 119(3), 382–389.

Grover, S. A., Coupal, L., & Hu, X. P. (1995). Identifying adults at increased risk of coronary disease. How well do the current cholesterol guidelines work? JAMA, 274(10), 801–806.

Khot, U. N., et al. (2003). Prevalence of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA, 290(7), 898–904.

Simon, A., Chironi, G., & Levenson, J. (2006). Performance of subclinical arterial disease detection as a screening test for coronary heart disease. Hypertension, 48(3), 392–396.

Goff, D.C., Jr. et al. (2013) ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Fuster, V., Lois, F., & Franco, M. (2010). Early identification of atherosclerotic disease by noninvasive imaging. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 7(6), 327–333.

Achenbach, S., et al. (2001). Noninvasive coronary angiography by magnetic resonance imaging, electron-beam computed tomography, and multislice computed tomography. American Journal of Cardiology, 88(2A), 70E–73E.

Ibanez, B., et al. (2007). [Novel imaging techniques for quantifying overall atherosclerotic burden]. Revista Española de Cardiología, 60(3), 299–309.

Yu, L., et al. (2009). Radiation dose reduction in computed tomography: techniques and future perspective. Medical Imaging, 1(1), 65–84.

Patel, S. N., et al. (2004). Emerging, noninvasive surrogate markers of atherosclerosis. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 6(1), 60–68.

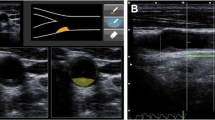

de Groot, E., et al. (2004). Measurement of arterial wall thickness as a surrogate marker for atherosclerosis. Circulation, 109(23 Suppl 1), III33–III38.

Baldassarre, D., et al. (2008). Carotid intima-media thickness and markers of inflammation, endothelial damage and hemostasis. Annals of Medicine, 40(1), 21–44.

Hodis, H. N., et al. (1998). The role of carotid arterial intima-media thickness in predicting clinical coronary events. Annals of Internal Medicine, 128(4), 262–269.

O’Leary, D. H., Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group, et al. (1999). Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 340(1), 14–22.

Bots, M. L., Hofman, A., & Grobbee, D. E. (1994). Common carotid intima-media thickness and lower extremity arterial atherosclerosis. The Rotterdam Study. Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis, 14(12), 1885–1891.

Baldassarre, D., et al. (2000). Carotid artery intima-media thickness measured by ultrasonography in normal clinical practice correlates well with atherosclerosis risk factors. Stroke, 31(10), 2426–2430.

Lorenz, M. W., et al. (2007). Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation, 115(4), 459–467.

Lind, L., et al. (2012). Effect of rosuvastatin on the echolucency of the common carotid intima-media in low-risk individuals: the METEOR trial. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, 25(10), 1120–1127 e1.

Smilde, T. J., et al. (2001). Effect of aggressive versus conventional lipid lowering on atherosclerosis progression in familial hypercholesterolaemia (ASAP): a prospective, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet, 357(9256), 577–581.

Raggi, P., et al. (2005). Aggressive versus moderate lipid-lowering therapy in hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women: Beyond Endorsed Lipid Lowering with EBT Scanning (BELLES). Circulation, 112(4), 563–571.

Yerly, P., et al. (2013). Association between conventional risk factors and different ultrasound-based markers of atherosclerosis at carotid and femoral levels in a middle-aged population. International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging, 29(3), 589–599.

Den Ruijter, H. M., et al. (2012). Common carotid intima-media thickness measurements in cardiovascular risk prediction: a meta-analysis. JAMA, 308(8), 796–803.

Inaba, Y., Chen, J. A., & Bergmann, S. R. (2012). Carotid plaque, compared with carotid intima-media thickness, more accurately predicts coronary artery disease events: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis, 220(1), 128–133.

Witte, D. R., et al. (2005). Is the association between flow-mediated dilation and cardiovascular risk limited to low-risk populations? Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 45(12), 1987–1993.

Greenland, P., et al. (2010). ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation, 122(25), e584–e636.

Laurent, S., et al. (2006). Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. European Heart Journal, 27(21), 2588–2605.

Ross, R. F., & Young, T. F. (1993). The nature and detection of mycoplasmal immunogens. Veterinary Microbiology, 37(3–4), 369–380.

Agatston, A. S., et al. (1990). Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 15(4), 827–832.

Hoff, J. A., et al. (2001). Age and gender distributions of coronary artery calcium detected by electron beam tomography in 35,246 adults. American Journal of Cardiology, 87(12), 1335–1339.

Kondos, G. T., et al. (2003). Electron-beam tomography coronary artery calcium and cardiac events: a 37-month follow-up of 5635 initially asymptomatic low- to intermediate-risk adults. Circulation, 107(20), 2571–2576.

Wong, N. D., et al. (2000). Coronary artery calcium evaluation by electron beam computed tomography and its relation to new cardiovascular events. American Journal of Cardiology, 86(5), 495–498.

Arad, Y., et al. (2005). Coronary calcification, coronary disease risk factors, C-reactive protein, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events: the St. Francis Heart Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 46(1), 158–165.

Greenland, P., et al. (2007). ACCF/AHA 2007 clinical expert consensus document on coronary artery calcium scoring by computed tomography in global cardiovascular risk assessment and in evaluation of patients with chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Clinical Expert Consensus Task Force (ACCF/AHA Writing Committee to Update the 2000 Expert Consensus Document on Electron Beam Computed Tomography) developed in collaboration with the Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 49(3), 378–402.

Bild, D. E., et al. (2005). Ethnic differences in coronary calcification: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation, 111(10), 1313–1320.

Fuster, V., et al. (2005). Atherothrombosis and high-risk plaque: Part II: approaches by noninvasive computed tomographic/magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 46(7), 1209–1218.

Pletcher, M. J., et al. (2013). Interpretation of the coronary artery calcium score in combination with conventional cardiovascular risk factors: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation, 128(10), 1076–1084.

Hamon, M., et al. (2006). Diagnostic performance of multislice spiral computed tomography of coronary arteries as compared with conventional invasive coronary angiography: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 48(9), 1896–1910.

Prat-Gonzalez, S., Sanz, J., & Garcia, M. J. (2008). Cardiac CT: indications and limitations. Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology, 36(1), 18–24.

Fernandez-Friera, L., et al. (2010). Lipid-rich obstructive coronary lesions is plaque characterization any important? JACC. Cardiovascular Imaging, 3(8), 893–895.

Hausleiter, J., et al. (2006). Radiation dose estimates from cardiac multislice computed tomography in daily practice: impact of different scanning protocols on effective dose estimates. Circulation, 113(10), 1305–1310.

Johri, A. M., et al. (2013). Can carotid bulb plaque assessment rule out significant coronary artery disease? A comparison of plaque quantification by two- and three-dimensional ultrasound. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, 26(1), 86–95.

Kalashyan, H., et al. (2014). Single sweep three-dimensional carotid ultrasound: reproducibility in plaque and artery volume measurements. Atherosclerosis, 232(2), 397–402.

Sillesen, H., et al. (2012). Carotid plaque burden as a measure of subclinical atherosclerosis: comparison with other tests for subclinical arterial disease in the high risk plaque BioImage study. JACC. Cardiovascular Imaging, 5(7), 681–689.

Makris, G. C., et al. (2011). Three-dimensional ultrasound imaging for the evaluation of carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis, 219(2), 377–383.

Corti, R., & Fuster, V. (2011). Imaging of atherosclerosis: magnetic resonance imaging. European Heart Journal, 32(14), 1709–19b.

Yuan, C., et al. (2001). In vivo accuracy of multispectral magnetic resonance imaging for identifying lipid-rich necrotic cores and intraplaque hemorrhage in advanced human carotid plaques. Circulation, 104(17), 2051–2056.

Fleg, J. L., et al. (2012). Detection of high-risk atherosclerotic plaque: report of the NHLBI Working Group on current status and future directions. JACC. Cardiovascular Imaging, 5(9), 941–955.

Corti, R., et al. (2005). Effects of aggressive versus conventional lipid-lowering therapy by simvastatin on human atherosclerotic lesions: a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial with high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 46(1), 106–112.

Corti, R., et al. (2002). Lipid lowering by simvastatin induces regression of human atherosclerotic lesions: two years’ follow-up by high-resolution noninvasive magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation, 106(23), 2884–2887.

Underhill, H. R., et al. (2008). Effect of rosuvastatin therapy on carotid plaque morphology and composition in moderately hypercholesterolemic patients: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging trial. American Heart Journal, 155(3), 584 e1–8.

Tang, T. Y., et al. (2008). Correlation of carotid atheromatous plaque inflammation using USPIO-enhanced MR imaging with degree of luminal stenosis. Stroke, 39(7), 2144–2147.

Tang, T. Y., et al. (2008). Correlation of carotid atheromatous plaque inflammation with biomechanical stress: utility of USPIO enhanced MR imaging and finite element analysis. Atherosclerosis, 196(2), 879–887.

Smith, B. R., et al. (2007). Localization to atherosclerotic plaque and biodistribution of biochemically derivatized superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) contrast particles for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Biomedical Microdevices, 9(5), 719–727.

von Zur Muhlen, C., et al. (2007). Superparamagnetic iron oxide binding and uptake as imaged by magnetic resonance is mediated by the integrin receptor Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18): implications on imaging of atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis, 193(1), 102–111.

Briley-Saebo, K. C., et al. (2011). Targeted iron oxide particles for in vivo magnetic resonance detection of atherosclerotic lesions with antibodies directed to oxidation-specific epitopes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 57(3), 337–347.

Hyafil, F., et al. (2011). Monitoring of arterial wall remodelling in atherosclerotic rabbits with a magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent binding to matrix metalloproteinases. European Heart Journal, 32(12), 1561–1571.

von Bary, C., et al. (2011). MRI of coronary wall remodeling in a swine model of coronary injury using an elastin-binding contrast agent. Circulation. Cardiovascular Imaging, 4(2), 147–155.

Winter, P. M., et al. (2003). Molecular imaging of angiogenesis in early-stage atherosclerosis with alpha (v) beta3-integrin-targeted nanoparticles. Circulation, 108(18), 2270–2274.

Rudd, J. H., et al. (2010). Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation by fluorodeoxyglucose with positron emission tomography: ready for prime time? Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 55(23), 2527–2535.

Mamede, M., et al. (2005). [18F]FDG uptake and PCNA, Glut-1, and Hexokinase-II expressions in cancers and inflammatory lesions of the lung. Neoplasia, 7(4), 369–379.

Ogawa, M., et al. (2004). (18)F-FDG accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques: immunohistochemical and PET imaging study. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 45(7), 1245–1250.

Tawakol, A., et al. (2005). Noninvasive in vivo measurement of vascular inflammation with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Journal of Nuclear Cardiology, 12(3), 294–301.

Rudd, J. H., et al. (2002). Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation, 105(23), 2708–2711.

Davies, J. R., et al. (2005). Identification of culprit lesions after transient ischemic attack by combined 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography and high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke, 36(12), 2642–2647.

Tahara, N., et al. (2006). Simvastatin attenuates plaque inflammation: evaluation by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 48(9), 1825–1831.

Nikhil, V., & Joshi, T. A. (2014). Williams Michelle, et al., 18F-Fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet, 383, 705–713.

Aikawa, E., et al. (2007). Osteogenesis associates with inflammation in early-stage atherosclerosis evaluated by molecular imaging in vivo. Circulation, 116(24), 2841–2850.

Ripa, R. S., et al. (2013). Feasibility of simultaneous PET/MR of the carotid artery: first clinical experience and comparison to PET/CT. American Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, 3(4), 361–371.

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC). (1989). Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. American Journal of Epidemiology, 129(4), 687–702.

Bild, D. E., et al. (2002). Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. American Journal of Epidemiology, 156(9), 871–881.

Falk, E., et al. (2011). The high-risk plaque initiative: primary prevention of atherothrombotic events in the asymptomatic population. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 13(5), 359–366.

Ortiz, A., Jiménez-Borreguero, L., Peñalvo, J. L., Ordovas, J. M., Mocoroa, A., Fernandez-Friera, L., et al. (2013). The Progression and Early Detection of Subclinical Atherosclerosis (PESA) study: rationale and design. American Heart Journal, 133, 990–998.

Fuster, V., & Vahl, T. P. (2010). The role of noninvasive imaging in promoting cardiovascular health. Journal of Nuclear Cardiology, 17(5), 781–790.

Peters, S. A., et al. (2012). Improvements in risk stratification for the occurrence of cardiovascular disease by imaging subclinical atherosclerosis: a systematic review. Heart, 98(3), 177–184.

Naghavi, M., et al. (2006). From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient—Part III: executive summary of the Screening for Heart Attack Prevention and Education (SHAPE) Task Force report. American Journal of Cardiology, 98(2A), 2H–15H.

Stein, J. H., et al. (2008). Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, 21(2), 93–111. quiz 189–90.

Perk, J., et al. (2012). European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version, The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). G Ital Cardiology (Rome), 14(5), 328–392.

Sheikine, Y., & Akram, K. (2010). FDG-PET imaging of atherosclerosis: Do we know what we see? Atherosclerosis, 211(2), 371–380.

Ferket, B. S., et al. (2011). Systematic review of guidelines on imaging of asymptomatic coronary artery disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 57(15), 1591–1600.

Hecht, H. S., et al. (2006). Coronary artery calcium scanning: clinical paradigms for cardiac risk assessment and treatment. American Heart Journal, 151(6), 1139–1146.

Taylor, A. J., et al. (2005). Coronary calcium independently predicts incident premature coronary heart disease over measured cardiovascular risk factors: mean three-year outcomes in the Prospective Army Coronary Calcium (PACC) project. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 46(5), 807–814.

Raggi, P., et al. (2005). Progression of coronary artery calcium and occurrence of myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Hypertension, 46(1), 238–243.

Arad, Y., et al. (2005). Treatment of asymptomatic adults with elevated coronary calcium scores with atorvastatin, vitamin C, and vitamin E: the St. Francis Heart Study randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 46(1), 166–172.

Greenland, P., et al. (2000). Prevention Conference V: beyond secondary prevention: identifying the high-risk patient for primary prevention: noninvasive tests of atherosclerotic burden: Writing Group III. Circulation, 101(1), E16–E22.

Santos, R. D., & Nasir, K. (2009). Insights into atherosclerosis from invasive and non-invasive imaging studies: Should we treat subclinical atherosclerosis? Atherosclerosis, 205(2), 349–356.

Furberg, C. D., et al. (1994). Effect of lovastatin on early carotid atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Progression Study (ACAPS) Research Group. Circulation, 90(4), 1679–1687.

Salonen, R., et al. (1995). Kuopio Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (KAPS). A population-based primary preventive trial of the effect of LDL lowering on atherosclerotic progression in carotid and femoral arteries. Circulation, 92(7), 1758–1764.

Toth, P. P. (2008). Subclinical atherosclerosis: what it is, what it means and what we can do about it. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 62(8), 1246–1254.

Taylor, A. J., et al. (2002). ARBITER: Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol: a randomized trial comparing the effects of atorvastatin and pravastatin on carotid intima medial thickness. Circulation, 106(16), 2055–2060.

Lauer, M. S. (2010). Screening asymptomatic subjects for subclinical atherosclerosis: not so obvious. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 56(2), 106–108.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr. Simon Bartlett (CNIC editing services) for his proficient revision of the language in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Associate Editor Angela Taylor oversaw the review of this article

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández-Friera, L., Ibáñez, B. & Fuster, V. Imaging Subclinical Atherosclerosis: Is It Ready for Prime Time? A Review. J. of Cardiovasc. Trans. Res. 7, 623–634 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12265-014-9582-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12265-014-9582-4