Abstract

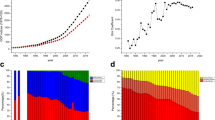

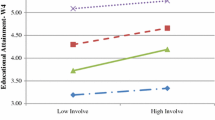

Poverty has long been known to be strongly correlated with academic achievement. The Federal Government, the State of Georgia, and many other states have adopted the policy of reporting school-level poverty by the percentage of students eligible for free and reduced price lunch. However, as we show in this article, there is a severe restriction of range in the upper end of the free and reduced price lunch variable. The result is that when free and reduced price lunch is used as a proxy for poverty, the restriction in range can cause schools with students whose families tend to be just below the poverty threshold to ostensibly have the same level of poverty as schools with students whose families tend to be extremely poor. This can result in the systemic misallocation of resources from the schools with the most need and the miscalculation of value-added accountability estimates. The purpose of this study is to illustrate this phenomenon with recent pre-existing academic achievement and free and reduced price lunch data from over 1200 elementary schools in the State of Georgia.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anyon, J. (1997). Ghetto schooling: A political economy of urban educational reform. New York: Teachers College Press.

Braun, H. I. (2005). Using student progress to evaluate teachers: A primer on value-added models [ETS Policy Information Center Report]. Retrieved from https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/PICVAM.pdf.

Cruse, C., & Powers, D. (2006). Estimating school district poverty from free and reduced price lunch. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/did/www/saipe/publications/files/CrusePowers2006asa.pdf.

DeNavas-Walt, C., & Proctor, B. D. (2014). Income and poverty in the United States: 2013 [U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-249]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p60-249.pdf.

Duncan, G. J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1997). Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage.

Endahl, J. (2006). Accuracy of SFA processing of school lunch applications: Regional Office Review of Applications (RORA) 2006. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/rora2006.pdf.

Feinstein, J. S. (1993). The relationship between socio-economic status and health. Milbank Quarterly, 71(2), 279–322.

Georgia Department of Education. (2012a). 2012 CRCT score interpretation guide. Retrieved from www.doe.k12.ga.us.

Georgia Department of Education. (2012b). Enrollment by ethnicity/race, gender, and grade level (March 1, 2012, FTE, Statewide). Retrieved from http://app3.doe.k12.ga.us/ows-bin/owa/fte_pack_ethnicsex.entry_form.

Kurki, A., Boyle, A., & Aledjem, D. A. (2005, April). Beyond free lunch—Alternative poverty measures in educational research and program evaluation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/AD90C18Fd01_0.pdf.

Macartney, S. (2011). Child poverty in the United States 2009 and 2010: Selected race groups and Hispanic origin [U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Brief]. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/acsbr10-05.pdf.

Maples, J. J., & Bell, W. R. (2005). Evaluation of school district poverty estimates: Predictive models using IRS income tax data. Proceedings of the Section on Government Statistics, American Statistical Association.

Murali, V., & Oyebode, F. (2004). Poverty, social inequality, and mental health. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 10, 216–224. doi:10.1192/apt.10.3.216.

National Center for Educational Statistics. (2006). Public elementary/secondary school universe survey. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/pubschuniv.asp.

Prejean-Harris, R. (2013). The relationship between standards-based reporting and third-grade mathematics and science achievement. Retrieved from Proquest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order No. 3573420).

Ravitch, D. (2010). The death and life of the great American school system: How testing and choice are undermining education. New York: Basic Books.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2011). Child nutrition guidelines—Income eligibility guidelines [Notice]. Federal Register, 76(58), 16724–16725. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/IEGs11-12.pdf.

White, K. R. (1982). The relation between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 91(3), 461–481.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Randolph, J.J., Prejean-Harris, R. The Negative Consequences of Using Percent of Free and Reduced Lunch as a Measure of Poverty in Schools: the Case of the State of Georgia. Child Ind Res 10, 461–471 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9391-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9391-1