Abstract

Background

Disclosure of the use of complementary health approaches (CHA) is an important yet understudied health behavior with important implications for patient care. Yet research into disclosure of CHA has been atheoretical and neglected the role of health beliefs.

Purpose

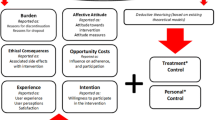

Using a consumer commitment model of CHA use as a guiding conceptual framework, the current study tests the hypotheses that perceived positive CHA outcomes (utilitarian values) and positive CHA beliefs (symbolic values) are associated with disclosure of CHA to conventional care providers in a nationally representative US sample.

Methods

From a sample of 33,594 with CHA use information from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), a subsample of 7348 who used CHA within the past 12 months was analyzed. The 2012 NHIS is a cross-sectional survey of the non-institutionalized US adult population, which includes the most recent nationally representative CHA use data.

Results

The 63.2% who disclosed CHA use were older, were less educated, and had visited a health care provider in the past year. Weighted logistic regression analyses controlling for demographic variables revealed that those who disclosed were more likely to report experiencing positive psychological (improved coping and well-being) and physical outcomes (better sleep, improved health) from CHA and hold positive CHA-related beliefs.

Conclusions

CHA users who perceive physical and psychological benefits from CHA use and who hold positive attitudes towards CHA are more likely to disclose their CHA use. Findings support the relevance of a consumer commitment perspective for understanding CHA disclosure and suggest CHA disclosure as an important proactive health behavior that warrants further attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

(IOM) Institute of Medicine. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. 2005.

Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States--prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993, 328:246–252.

Upchurch DM, Wexler Rainisch B. A sociobehavioral model of use of complementary and alternative medicine providers, products, and practices findings from the 2007 national health interview survey. Journal of Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013, 18:100–107.

Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults: United States, 2002–2012. National Health Statistics Report; 2015.

Sirois FM, Gick ML. An investigation of the health beliefs and motivations of complementary medicine clients. Social Science and Medicine. 2002, 55:1025–1037.

Sirois FM, Purc-Stephenson R. Consumer decision factors for initial and long-term use of complementary and alternative medicine. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2008, 3:3–20.

Hsiao A, Wong MD, Kanouse DE, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use and substitution for conventional therapy by HIV-infected patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003, 33:157–165.

Harrison A, Verhoef M. Understanding coordination of care from the consumer’s perspective in a regional health system. Health Services Research. 2002, 37:1031–1054.

Tabali M, Ostermann T, Jeschke E, Witt CM, Matthes H. Adverse drug reactions for CAM and conventional drugs detected in a network of physicians certified to prescribe CAM drugs. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 2012, 18:427–438.

Curtis P, Gaylord S. Safety issues in the interaction of conventional, complementary, and alternative health care. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2005, 10:3–31.

Kretchy IA, Owusu-Daaku F, Danquah S. Patterns and determinants of the use of complementary and alternative medicine: A cross-sectional study of hypertensive patients in Ghana. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014, 14:1–7.

Nahin RL, Dahlhamer JM, Taylor BL, et al. Health behaviors and risk factors in those who use complementary and alternative medicine. Biomed Central Public Health. 2007;7.

Upchurch DM, Rainisch BW. The importance of wellness among users of complementary and alternative medicine: Findings from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015, 15:362.

Williams-Piehota P, Sirois FM, Bann C, Isenberg KB, Walsh EG. Agents of change: How do complementary and alternative medicine providers play a role in health behavior change? Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine. 2011, 17:22–30.

Littlewood RA, Vanable PA. The relationship between CAM use and adherence to antiretroviral therapies among persons living with HIV. Health Psychology. 2014, 33:660–667.

Bello N, Winit-Watjana W, Baqir W, McGarry K. Disclosure and adverse effects of complementary and alternative medicine used by hospitalized patients in the North East of England. Pharmacy Practice. 2012, 10:125–135.

Faith J, Thorburn S, Tippens KM. Examining CAM use disclosure using the behavioral model of health services use. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2013, 21:501–508.

Ge J, Fishman J, Vapiwala N, et al. Patient-physician communication about complementary and alternative medicine in a radiation oncology setting. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2013, 85:e1–6.

Rausch S, Winegardner F, Kruk K, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine: Use and disclosure in radiation oncology community practice. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011, 19:521–529.

Liu C, Yang Y, Gange SJ, et al. Disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine use to health care providers among HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care St 2009, 23:965–971.

Chao MT, Wade C, Kronenberg F. Disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine to conventional medical providers: variation by race/ethnicity and type of CAM. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008, 100:1341–1349.

Jou J, Johnson P. Nondisclosure of complementary and alternative medicine use to primary care physicians: Findings from the 2012 national health interview survey. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016, 176:545–546.

Shim J-M, Schneider J, Curlin FA: Patterns of user disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use. Medical Care. 2014, 52:704–708.

Arthur KN, Belliard JC, Hardin SB, et al.: Reasons to use and disclose use of complementary medicine use—An insight from cancer patients. Cancer and Clinical Oncology. 2013, 2.

Sirois FM. Looking beyond the barriers: Practical and symbolic factors associated with disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use. European Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2014, 6:545–551.

McNair RP, Hegarty K, Taft A. From silence to sensitivity: A new identity disclosure model to facilitate disclosure for same-sex attracted women in general practice consultations. Social Science & Medicine. 2012, 75:208–216.

Ajzen I. Models of human social behavior and their application to health psychology. Psychology and Health. 1998, 13:735–739.

Bishop FL, Yardley L, Lewith GT. A systematic review of beliefs involved in the use of complementary and alternative medicine. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007, 12:851–867.

Chang H-Y, Chang H-L, Siren B. Exploring the decision to disclose the use of natural products among outpatients: A mixed-method study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013, 13:319–319.

Sirois FM, Salamonsen A, Kristoffersen AE. Reasons for continuing use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in students: A consumer commitment model. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016, 16:1–9.

Shumay DM, Maskarinec G, Gotay CC, Heiby EM, Kakai H. Determinants of the degree of complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with cancer. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2002, 8:661–671.

Balneaves LG, Bottorff JL, Hislop TG, Herbert C. Levels of commitment: Exploring complementary therapy use by women with breast cancer. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2006, 12:459–466.

Wang G. Attitudinal correlates of brand commitment: An empirical study. Journal of Relationship Marketing. 2002, 1:57–76.

Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. In P. Norman, C. Abraham and M. Conner (eds), Understanding and Changing Health Behavior: From Health Beliefs to Self-Regulation. Amsterdam: Harwood, 2000, 299–339.

Sirois FM. Treatment seeking and experience with complementary/alternative medicine: A continuum of choice. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2002, 8:127–134.

Lupton D. Consumerism, reflexivity and the medical encounter. Social Science and Medicine. 1997, 45:373–381.

Sirois FM. Motivations for consulting complementary and alternative medicine practitioners: A comparison of consumers from 1997–8 and 2005. BioMed Central Complement Altern Med. 2008;8.

Thomson P, Jones J, Evans JM, Leslie SL. Factors influencing the use of complementary and alternative medicine and whether patients inform their primary care physician. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2012, 20:45–53.

Arcury TA, Bell RA, Altizer KP, et al. Attitudes of older adults regarding disclosure of complementary therapy use to physicians. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2013, 32:627–645.

Statistics NCfH. Data file documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2012. In: N. C. f. H. Statistics, ed. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013.

Parsons VL, Moriarity CL, Jonas K. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2015. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2014;2.

Stata Statistical Software, Release 12.0. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2010.

Robinson AR, Crane LA, Davidson AJ, Steiner JF. Association between use of complementary/alternative medicine and health-related behaviors among health fair participants. Preventive Medicine. 2002, 34:51–57.

Garrow D, Egede LE. Association between complementary and alternative medicine use, preventive care practices, and use of conventional medical services among adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006, 29:15–19.

Stokley S, Cullen KA, Kennedy A, Bardenheier BH. Adult vaccination coverage levels among users of complementary/alternative medicine—Results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2008, 8:1–8.

Stub T, Musial F, Quandt SA, et al. Mapping the risk perception and communication gap between different professions of healthcare providers in cancer care: A cross-sectional protocol. BMJ Open. 2015;5.

Bishop FL, Dima AL, Ngui J, et al. “Lovely pie in the sky plans”: A qualitative study of clinicians’ perspectives on guidelines for managing low back pain in primary care in England. Spine. 2015, 40:1842–1850.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the National Center of Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) of the National Institute of Health (NIH) to Dr. Upchurch (grant number AT002156). The authors also acknowledge the Department of Community Health Sciences, UCLA, for support for Ms. Riess.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Authors Fuschia M. Sirois, Helene Riess, and Dawn M. Upchurch declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Statement Regarding Ethical Approval Not Being Required

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a large, publicly available, multipurpose health data set that is widely available to multiple investigators. Technically, our research has “no human subjects” because the data are de-identified, publicly available. Secondary data analysis of this type does not have to require IRB approval.

About this article

Cite this article

Sirois, F.M., Riess, H. & Upchurch, D.M. Implicit Reasons for Disclosure of the Use of Complementary Health Approaches (CHA): a Consumer Commitment Perspective. ann. behav. med. 51, 764–774 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-017-9900-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-017-9900-6