Abstract

Background

Cancer can challenge important life goals for young adult survivors. Poor goal navigation skills might disrupt self-regulation and interfere with coping efforts, particularly approach-oriented attempts. Two studies are presented that investigated relationships among goal navigation processes, approach-oriented coping, and adjustment (i.e., social, emotional, and functional well-being) in separate samples of young adults with testicular cancer.

Methods

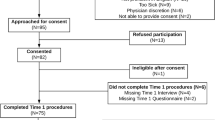

In study 1, in-depth interviews (N = 21) were analyzed using thematic analysis to understand experiences of goal pursuit following cancer. In study 2, 171 men completed measures of goal navigation, coping, and adjustment to cancer.

Results

In study 1, three prominent themes emerged: goal clarification, goal engagement and disengagement, and responses to disrupted goals. Regression analyses in study 2 revealed that goal navigation skills were positively associated with emotional (B = .35, p < .001), social (B = .24, p < .01), and functional (B = .28, p < .001) well-being, as was approach-oriented coping (B = .22, p < .01; B = .32, p < .001; B = .26, p < .001, respectively). Goal navigation moderated associations between approach-oriented coping and well-being, such that those with low goal navigation ability and low approach-oriented coping reported lower well-being.

Conclusions

Goal navigation skills and approach-oriented coping have unique and interactive relationships with adjustment to testicular cancer. They likely represent important independent targets for intervention, and goal navigation skills might also buffer the negative consequences of low use of approach-oriented coping.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hoyt MA, Stanton AL. Adjustment to chronic illness. In: Baum AS, Revenson TA, Singer JE, eds. Handbook of Health Psychology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2012: 219-246.

Hullman SE, Robb SL, Rand KL. Life goals in patients with cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2015. doi:10.1002/pon.3852.

Thompson E, Stanton AL, Bower JE. Situational and dispositional goal adjustment in the context of metastatic cancer. J Pers. 2013; 81: 441-451.

Eiser C, Aura K. Psychological support. In: Bleyer WA, Barr RD, eds. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. New York, NY: Springer; 2007: 365-373.

Shama W, Lucchetta S. Psychosocial issues of the adolescent cancer patient and the development of the teenage outreach program (TOP). J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007; 25: 99-112.

Arnett JJ. New horizons in emerging and young adulthood. In: Booth A, Crouter N, eds. Early Adulthood in a Family Context. New York, NY: Springer; 2012: 231-244.

Wrosch C, Scheier MF, Miller GE, et al. Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: Goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2003; 29: 1494-1508.

Salsman JM, Garcia SF, Yanez B, et al. Physical, emotional, and social health differences between posttreatment young adults with cancer and matched healthy controls. Cancer. 2014; 120: 2247-2254.

Heckhausen J, Wrosch C, Schulz R. A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychol Rev. 2010; 117: 32.

Carver CS, Scheier MF. Attention and Self-Regulation: A Control-Theory Approach to Human Behavior. New York, NY: Springer; 1981.

Hoyt MA, Cano SJ, Saigal CS, et al. Health-related quality of life in young men with testicular cancer: Validation of the Cancer Assessment for Young Adults (CAYA). J Cancer Surviv. 2013; 7: 630-640.

Heckhausen J, Wrosch C, Fleeson W. Developmental regulation before and after a developmental deadline: The sample case of “biological clock” for childbearing. Psychol Aging. 2001; 16: 400.

Wrosch C. Self-regulation of unattainable goals. In: Folkman S, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010: 319-333.

Schroevers MJ, Kraaij V, Garnefski N. Cancer patients’ experience of positive and negative changes due to the illness: Relationships with psychological well-being, coping, and goal reengagement. Psychooncology. 2011; 20: 165-172.

Haase CM, Heckhausen J, Worsch C. Developmental regulation across the life span: Toward a new synthesis. Dev Psychol. 2013; 49: 964-972.

Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000; 55: 469.

Schulenberg JE, Bryant AL, O’Malley PM. Taking hold of some kind of life: How developmental tasks relate to trajectories of well-being during the transition to adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2004; 16: 1119-1140.

Ebata AT, Moos RH. Coping and adjustment in distressed and healthy adolescents. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1991; 12: 33-54.

Kliewer W. Children’s coping with chronic illness. In: Wolchik S, Sandler I, eds. Handbook of Children’s Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1997: 275-300.

Aldridge AA, Roesch SC. Coping and adjustment in children with cancer: A meta-analytic study. J Behav Med. 2000; 30: 115-129.

ACS. Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2012.

Huang L, Cronin KA, Johnson KA, et al. Improved survival time: What can survival cure models tell us about population‐based survival improvements in late‐stage colorectal, ovarian, and testicular cancer? Cancer. 2008; 112: 2289-2300.

Morse J. Designing funded qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994: 220-235.

Braun V, Clarke C. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3: 77-101.

McPherson G, Thorne S. Exploiting exceptions to enhance interpretive qualitative health: Insight from a study of cancer communication. Int J Qual Methods. 2006; 5: 1-11.

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief Cope. Int J Behav Med. 1997; 4: 92-100.

Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Cameron CL, et al. Emotionally expressive coping predicts psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000; 68: 875-882.

Hoyt MA, Thomas KS, Epstein DR, et al. Coping style and sleep quality in men with cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2009; 37: 88-93.

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993; 11: 570-579.

Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1991.

Preacher K. A Primer on Interaction Effects in Multiple Linear Regression. copyrighted manuscript: Chapel Hill, NC; 2003.

Kraaij V, Van der Veek SMC, Garnefski N, et al. Coping, goal adjustment, and psychological well-being in HIV-infected men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008; 22: 395-402.

Thompson EH, Woodward JT, Stanton AL. Dyadic goal appraisal during treatment for infertility: How do different perspectives relate to partners’ adjustment? Int J Behav Med. 2012; 19: 252-259.

Rasmussen HN, Wrosch C, Scheier MF, et al. Self-regulation processes and health: The importance of optimism and goal adjustment. J Pers. 2006; 74: 1721-1747.

Folkman S. Positive psychological stress and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med. 1997; 45: 1207-1221.

Miller GE, Wrosch C. You’ve gotta know when to fold ‘em: Goal disengagement and systemic inflammation in adolescence. Psychol Sci. 2007; 18: 773-777.

Wrosch C, Miller GE, Scheier MF, et al. Giving up on unattainable goals: Benefits for health? Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2007; 33: 251-265.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000; 55: 68-78.

Snyder CR. Hope Theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychol Inq. 2002; 13: 249-275.

Jacobs N, Hagger MS, Streukens S, et al. Testing an integrated model of the theory of planned behaviour and self‐determination theory for different energy balance‐related behaviours and intervention intensities. Br J Health Psychol. 2011; 16: 113-134.

Thornton LM, Cheavens JS, Heitzman CA, et al. Test of mindfulness and hope components in a psychological intervention for women with cancer recurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014; 82: 1087-1100.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from the Livestrong Foundation and the National Institute of Mental Health (5T32MH015750 and 5T32MH078788). We thank Lisa Rubin, Bennett Allen, and Dulci Pitagora for their contributions to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards Authors Hoyt, Gamarel, Saigal, and Stanton declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 61 kb)

About this article

Cite this article

Hoyt, M.A., Gamarel, K.E., Saigal, C.S. et al. Goal Navigation, Approach-Oriented Coping, and Adjustment in Young Men with Testicular Cancer. ann. behav. med. 50, 572–581 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9785-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9785-9