Abstract

The importance of environmental consideration for companies is mounting. This applies particularly well to logistics service providers (LSPs) who will have a possibility to compete by being greener than their competitors by offering services that include different green practices. As their customers play a vital role with regard to the extent to which LSPs can include environmental practices in their business, the interface between these actors is of interest. The purpose of this article is to describe and explain how environmental practices are reflected in offerings and requirements on the logistics market. A systematic literature review of what has been published on environmental practices as parts of offerings and requirements was complemented by a wider literature review. Empirical data were collected through a home page scan and a case study of four LSP–shipper dyads. With a starting point in stakeholder theory, the different data sets were analysed separately as well as combined, and similarities and differences were discussed. The findings point to differences in the way that LSPs and shippers offer and require environmental practices on their home pages and reasons for this are suggested to be due to their different types of stakeholders. Further, the environmental practices in relationships between LSP and shippers are often more relationship specific than practices on home pages. Based on the combined findings of the data sets, a classification of environmental practices as reflected in offerings and requirements on the logistics market is proposed. The article is mainly based on companies’ practices in Sweden and thereby provides a possibility to extend the research into other countries as well. By taking two perspectives, the findings from this research can have implications both for purchasing and marketing of logistic services. The paper suggests which environmental practices that LSPs and shippers can offer or require in different stages of their business relationships. Contrary to most research within green logistics, this paper takes a business perspective on environmental practices. Further, the dual perspective of LSPs and shippers taken in this paper offers novel insight into how environmental practices can be included at different stages of LSP–shipper relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Research on green logistics is growing in importance and has over the past decade received increased attention both in research literature and among practitioners. Green logistics is a wide area [34], and over the years, the focus has expanded from more technology-driven improvements of the transportation system and modal split towards city logistics (see for example [3]), reverse logistics [5, 23, 57], logistics in corporate environmental strategies [2, 38, 68], and green supply chain management (GSCM) [51, 56, 62].

The goal of greening logistics can be reached in different ways, but basically green logistics focuses on increased and better use of environmentally friendlier technologies, and on reducing the total amount of goods transported [2], where the latter relates to the design and management of logistics systems. This implies that none of these ways by itself would be enough in order to reach ambitious carbon reduction goals, but efforts are needed in both areas (ibid.).

While literature on green logistics mainly take the perspective of the logistics system and seeks to green the system and its operations as such, quite little attention has been paid to the roles that different actors have in actually realising the suggested changes. Different types of actors or stakeholders directly participate in the logistics system, such as sellers and buyers of goods as well as various logistics service providers (LSPs), while other types are interested in, affected by and affect the logistics system, such as legislative bodies and interest groups. It has been argued that LSPs play a vital role as corporate actors in the greening of logistics since they often manage the resources directly connected to the negative externalities from logistics systems [67], but at the same time, they are providers to their customers, whose requirements to a large extent frame LSPs’ business. At the kernel of this question, the interplay between the LSPs and their customers is the service offering, as offered from LSPs, and as requested from their customers, here called the shippers.

In the light of this, it becomes vital to include different stakeholders and their roles in general, and LSPs and shippers in particular in the analysis of green logistics, in order to better understand the ways in which green logistics practices are communicated and accommodated among logistics companies and their customers. The inter-organisational perspective as such has been quite extensively addressed in research on GSCM (see for example [51, 53, 61]). The link between shippers and logistics companies is, however, sparsely addressed [32]. Addressing the interface between shippers and LSPs can bring new insights with regard to how green logistics parameters are addressed by the two sides.

While details of general, non-green logistics service offerings have been thoroughly described in literature (see for example [6, 46, 70]), environmental aspects of the logistics service offering are rarely, if ever, explicitly mentioned in the literature. In those rare cases that environmental issues are pointed out in relation to the service offering or requirement, they are treated in very general terms (see for example [28, 44, 53, 66]). The findings of Wolf and Seuring [66], for example, indicate that “environmental aspects have entered the class of order qualifiers” (p. 95) when logistics services are bought, but the authors never go into detail about what this aspect include. Lao et al. [28] suggest that “green logistics should be promoted to improve the image of 3PL service providers” (p. 45)—but again, the topic is mentioned in very general terms. Overall, very little literature explicitly addresses specific green logistics practices in terms of offerings or requirements beyond the level of stating the need for more offerings and requirements in general.

This situation can be put in contrast to the body of literature that deals with more general services and service offerings. Here, it is recognised that it is important to understand the various parts of services, for example to be able to measure service quality and control suppliers [28, 29, 41, 42]. This situation definitely applies also to the area of green logistics and service offerings and requirements. Taking a stakeholder perspective on green logistics services would hence bring a new dimension to the various green logistics practices that have been suggested in previous research (e.g. [10]). The purpose of this paper is therefore to describe and explain how environmental practices are reflected in offerings and requirements on the logistics market.

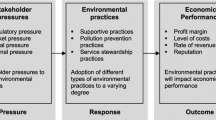

As a means to address the purpose, this paper takes its starting point in stakeholder theory. This is in line with Sarkis et al. [51], who in the context of green supply chain management argue that stakeholder analysis is particularly useful since environmental practices are not always perceived as necessary for a company’s competitive advantage, at the same time as they can be required by various stakeholders. A stakeholder is according to Freeman [18] any group or individual that affects or is affected by an organisation’s actions. Freeman [18] originally presented eleven different stakeholders (owners, customers, employees, suppliers, competitors, governments, consumer advocates, environmentalists, special interest groups, media, and local community organisations). Indeed several authors have identified a variety of stakeholder influences on LSPs’ environmental practises, such as from customers, competitors, and governments [21, 30, 34].

Several suggestions of categorisation of stakeholders have been brought forward within stakeholder theory [16, 51]. One division is suggested by Post et al. [45]: the corporation is viewed first in the context of stakeholders that are parts of its resource base, which in turn is part of industry structures, which is finally part of the social political arena. Stakeholders belonging to the resource base are more directly important to the corporation’s wealth than the ones in the industry structure, etc. Post et al. [45] further suggest that the corporation to a higher degree must consider the interest of the resource base group of stakeholders, which in their model includes investors, shareowners, and lenders; employees; and customers and users. This group is referred to by Kirchoff et al. [24] as the primary stakeholder group. The industry structure group [45] includes, e.g., supply chain associates and regulatory authorities, and the social political area gathers more general interest groups such as governments, citizens, and local communities. Kirchoff et al. [24] refer to these groups as secondary stakeholders. In the light of environmental impact from logistics and transportation, both primary and secondary stakeholders are likely to be affected and could thus be of relevance for the LSPs to take into account in relation to green practises included in their offerings.

A different classification if offered by Mitchell et al. [37], who suggest that a company’s stakeholders can be divided according to (1) their power to influence the firm, (2) the legitimacy of their relationship with the firm, and (3) the urgency of their claim on the firm. Research within GSCM has, for example, shown that the size of customers can influence the ability of companies to affect their suppliers in terms of environmental practices [25, 59]. Further, companies’ responsiveness to stakeholder needs is also suggested to be related to how close they are to final consumers [47]. Another parameter that could have an effect on the level of stakeholder consideration is the industry to which it belongs and its perceived negative environmental impacts by various stakeholders [17]. In other words, the visibility of an industry might very well have an impact on responsiveness towards stakeholders [47]. This appears to be of relevance for the transport industry and logistics industry ad; a report from DHL [11] illustrates this well:

Climate change and its consequences will have a far-reaching effect on logistics. As one of the largest producers of CO2 emissions, the logistics industry will find itself in a particularly difficult position—and under close scrutiny. (p. 52)

Based on the stakeholder perspective as presented above, this paper sets off to study environmental practices reflected as offerings and requirements on the logistics market. While the primary unit of analysis is the logistics market, described in terms of offerings and requirements of green logistics services, the stakeholder theory provides a wider perspective, which will support the explanatory parts of this paper.

The paper continues with a presentation of the research methods applied in this study and the rationale behind them. This is followed by the results from the systematic literature review combined with more general green logistics literature. Next, the empirical results from the home page scan and the case study, which includes four cases, are presented. Based on stakeholder theory, an analysis of the results is then conducted and this leads to a classification of environmental practices as reflected in offerings or requirements on the logistics market. The paper ends with conclusions and suggestions for further research.

2 Research method

This paper is based on a wide literature study as well as empirical a scan of company home pages (Study 1) and four case studies (Study 2), all of which are motivated by the exploratory aim of this paper. One important aspect of the research for this paper is that for all data collection methods, both the LSPs and the shippers have been studied. This way of addressing the problem is rare, but pointed out as important for improving supply chain environmental performance [9, 54].

The systematic literature study provides information on what has been published about environmental practices as a part of offerings or requirements of green logistics services. Due to the relatively scarce results from the literature search, additional literature within the field of green logistics helps to structure and enrich the findings. The findings from the home pages are then used to possibly widen the picture of offerings and requirements by adding more specific environmental practices within each of the general practices. Finally, the four cases, that include one relationship between an LSP and a shipper each, provide insights into environmental practices in specific buyer–supplier relationships. Whereas the home page scan potentially offers wide range of environmental practices, due to companies’ willingness to promote their environmental image, the cases offer insight into the relational perspective of the inclusion of environmental practices. Thus, although the cases could include similar environmental practices as found in the home page scan, the LSP–shipper cases could potentially include additional environmental practices relevant for the specific relationships.

2.1 Literature review

The literature review for this paper was conducted in two different steps. The first one was a systematic literature review that resulted in very few relevant hits. Because of this, a second literature review was conducted. The aim of the first literature review was to find papers that explicitly concerned offerings from LSPs or requirements from shippers. This also meant that the targeted papers needed to include details about the types of environmental practices that could be included in such offerings and/or requirements.

As the topic is novel, we selected a wide approach to literature, in order to illuminate the phenomenon, rather than choosing a specific perspective. Identification of search terms was inspired by the systematic review approach of Tranfield et al. [60]. Using the Business Source Premier database, the terms offer* and requir* were combined with the terms logistic*/supply chain*/transport* and environment*/green*/sustainab*. Thus, three terms were used in every search, and in total, eighteen searches were made. “Offer*” was used to cover the LSPs, while “requir*” was used to cover the shipper side.

Many of the articles that at first glance seemed relevant turned out to only mention “customer requirements” and then go on to discussing things that are not relevant for the purpose of this paper. This meant that they did not explicitly discuss offerings or requirements of environmental practices in any way. In the end, only 5 papers (see Table 1), out of 2,221 hits were identified as relevant for this study. Since the systematic literature search gave so few relevant hits, it was complemented with general literature within the field of environmental logistics.

As the systematic literature review did not reveal any unified constructs with regard to offerings and requirements of environmental practices, there was a need to identify another framework to take a stance from. One problem associated with existing ways of describing the environmental dimension of logistics and supply chains is that they are often rather narrow, which inhibits the need there is to take a more holistic perspective [64]. To be able to assess or even measure logistics from a market perspective, a first step was therefore to establish a framework that can help structure the wide area. As customers’ demands for green logistics services vary widely [22], it is important to span a wide range of practices than to establish a confined set of main practices.

McKinnon [34] has introduced an analytical model, which accounts for the complex relationships between different factors and logistics system externalities. The model accommodates parameters that address the logistics and transport system network design, management, as well as technological aspects. The model is aimed to analyse the logistics system as such and can be applied from a variety of perspectives, such as the shipper or the LSP perspective, and is thus very useful both for research and practitioners. The second part of the literature therefore took its starting point in the framework by McKinnon [34] and complemented by findings from previous research, ideas from discussions with peers and a snowball approach which revealed additional relevant articles. The findings from the systematic literature review were categorised into the framework by McKinnon [34] and/or into the additional categories that were identified during the literature reviews.

2.2 Study 1: The home page scan

The approach of studying companies’ environmental efforts through scanning of official web pages has previously been used by for example Bask and Kuula [4]. They motivate the choice of studying official web pages by the nature of interest of the research the involvement of multiple stakeholder perspectives. This is applicable also in the study for this paper, as the interest of various stakeholders might influence the environmental practices as offered and required on the home pages and thus give a wide spectrum of such practices in this specific context. The marketing objective of home pages also contributes to the purpose of this paper because of their potential aim to highlight environmental practices to present as well as future customers. According to the reasoning above, stakeholders of various types can have an impact on the environmental content of home page and this gives opportunities to analyse the findings in relation to the stakeholder perspective (e.g. [18]) taken in this paper.

Although suitable for this specific study, there are some drawbacks when including home pages in research. One such potential problem is that the credibility (see [8]) of home pages can be questioned since they are used both for information and marketing purposes and therefore do not show the actual behaviour of the companies. However, as argued above, this is not a problematic issue in this paper because of its purpose and because of the stakeholder perspective taken.

The companies studied in the home page scan were selected based on specific criteria (cf. [69]; they are all well known and often large companies with a stated high environmental ambition. Lists provided by Global 100, Global 500 Carbon disclosure project and DJSI supersector leaders served as inspiration in identifying the companies. In total, 15 companies were selected for this study (see Table 2). Six out of these were LSPs and nine were shippers. The provider companies comprise four international companies (large players on the Swedish market) and two with the main part of their activities within Sweden. The shipper companies are all international companies with considerable activities in Sweden (Sweden based as well as based in other countries). The rationale behind choosing companies with a connection to the Swedish market is that Sweden is generally seen as an environmentally conscious country [15], which in turn increases the likeliness of finding information about environmental practices during the scan.

The companies were investigated by visiting the official web page of each company. Any information regarding environmental practices as a part of logistics services as offerings (LSPs) or requirements (shippers) were documented. The initial scan often led to specific environmental theme pages, which were investigated, but also the general offering pages were scanned. Some companies referred to a specific sustainability report, and these reports were then scanned for environmental practices as parts of offerings and requirements relating to logistics and the environment.

The investigation included all the contents of the home pages, including all accessible material such as sustainability reports and press releases, as this information can be considered as an imprint of what a logistics company or a shipper is willing to state officially. Interestingly, the shippers did not address their environmental requirements on LSPs on their general home pages, but rather on their specific environmental or CSR home pages, and in their environmental/CSR reports.

We searched for phrases and statements that addressed environmental aspects of logistics and transportation and that could be interpreted as either an offering to existing and potential customers (from the LSPs), or a requirement on LSPs (from the shippers). Statements such as “We develop increasingly environmentally friendly transport and logistics services” were not registered as they were considered to general, while more specific statements were categorised. For example, “Calculation of customers’ emissions” was categorised as an LSP offering relating to emission data, and “We expect transport providers to follow established environmental standards” was categorised as a shipper requirement related to environmental management systems. General statements, mainly among the shippers, relating to environmental responsibility regarding their own products and customer offers or to product suppliers were not recorded in this investigation.

2.3 Study 2: The case study

The home pages have, as described above, the potential to illustrate a wide spectrum of environmental practices as offered and required on the logistics market. This is mainly due to their potential to reach a large number of stakeholders (see, e.g. [4]). However, an analysis based only on home pages clearly lacks the fuller picture that a case study provides [1]. In order to take another type of stakeholder perspective, namely a very clear relationship perspective including only LSPs and shippers, the research for this paper also includes a case study. The two differing perspectives of home pages and cases were believed to offer deeper insight into environmental practices as parts of offerings and requirements than would the methods do alone.

Four relationships between LSPs and shippers were studied, and Fig. 1 illustrates the general idea behind the cases. The companies were chosen because of their interest in and work with environmental practices, in line with intensity sampling logic described by Patton [43]. Two LSPs were first selected as one part in two buyer–supplier relationships each, and after that, four shippers were chosen. Based on the logic of theoretical sampling (see for example [13]), the LSPs were chosen for two different reasons: first, they were chosen because of the above-mentioned environmental criterion, which increases the likeliness that they contribute to theoretical insight within the field of environmental logistics. Secondly, the two LSPs were chosen because of their differences in size and market focus, and these differences were believed to offer contrary results that could shed more light on different environmental practices.

The LSP that is labelled LSP X in Fig. 1 is Alltransport in Östergötland AB (Alltransport). Alltransport was interested in environmental issues and was selected as an example of good practice [43]. They were for example given an award for their sustainability report in 2008 [58]. The second LSP was selected for both heterogeneous and homogenous reasons [43]. The LSP, DHL, is considerably larger than Alltransport and active on a global market. It is also a company that recognises the environmental impacts that their activities cause and tries to make up for these impacts in different ways. DHL has for example won an IT-award in the category “the sustainable project of the year” for its emission simulation tool. As can be noted above, DHL is included in the home page scan as well. As mentioned in the initial section of this chapter, the relationship perspective is believed to be able to offer additional insight into the environmental practices as part of green logistics service offerings and requirements. Thus, even though there is a risk of a replication of environmental practices from the home page scan when DHL is included in the case study, the fact that “green relationships” were targeted is believed to enrich the results from the home page scan, including the findings from DHL.

When the decision was made about which LSPs to study, the shippers were chosen in collaboration with representatives from the two LSPs. Alltransport’s two customers were Holmen Paper AB and Onninen, while the two customers selected for DHL were SECO Tools AB and Ericsson. All four companies’ home pages were checked to make sure that some attention to environmental issues was given there. Table 3 shows some key facts about the four cases and illustrates similarities and difference between the cases.

The case study data for this paper mainly come from interviews, and one or two representatives from each company were interviewed. For dependability reasons [8], the questions followed an interview guide with open-ended questions. In relation to this paper, each interviewee was asked to describe the environmental aspects of the specific relationship. So even though the respondents were deliberately not asked to list environmental practices explicitly, they were asked about green offerings and requirements in their specific relationships and these are singled out in then analysis of the cases. All informants reviewed a draft of the case study report which strengthens the credibility of the case study [8].

2.4 Analysis

The first step of analysis was to establish an initial set of environmental practices of logistics offerings and requirements. This categorisation was based on green logistics literature and deductive reasoning and is also the basis for the presentation of the literature review. Due to a limited number of relevant papers from the systematic literature review, the frame of reference takes its starting point in general literature within the field of green logistics. In the frame of reference, ten categories derived from literature are presented. After an initial presentation of each environmental practice that could be a part of offerings from LSPs or requirements from shippers, the findings from the systematic literature were categorised into the ten categories.

The second step of the analysis was to use the complementary pictures from the literature and the two empirical data sets to illustrate and specify environmental practices as offered or required on the logistics market. As the home page scan included both LSP and shipper perspectives, the empirical results were analysed based on the differences between these two sides of the logistics market. The types of environmental practices as well as how straightforward these practices were presented (on the immediate home pages, on specific environmental/CSR home pages or in environmental/CSR reports) were analysed. Explanations for the discrepancies were guided by stakeholder theory.

Because of their relationship nature, the cases were analysed in a different way than the home pages. Based on the types of environmental practices identified in each of the four LSP–shipper cases, a comparison between the cases was made. The findings of both data sets were then compared based on stakeholder theory. Finally, the two data sets studied for this paper opened up for a classification of the environmental practices as reflected in offerings and requirements on the logistics market. The classification is the result of an iterative process, in which the different practices were discussed between the researchers, who stepwise revisited both literature and the empirical material before the final category model was set.

2.5 Research quality

While the use of pre-defined search terms often produces a trustworthy and repeatable result, the structured search in this research did not deliver many results, why it had to be complemented with a second literature study based on peer suggestions and snowball sampling. While the second type of literature study clearly has the strength of being purposeful and to produce useful results, it is highly dependent on the researchers and their previous knowledge of the area. The authors have focused on a specific literature area—green logistics—and taken care to select main works as well as performed snowball sampling relating to interesting publications. In addition, the authors have discussed the research with colleagues and taken advice to numerous articles, of which some proved useful for the research purpose. Each suggested source has been analysed by the researchers involved, which is referred to as analyst triangulation [43].

In this research, the home page scan resembles qualitative rather than quantitative research and is thus discussed in qualitative research terms. In the home page scan (Study 1), research was limited to home pages related to companies based in, or with a considerable presence in Sweden. Although the rationale for selecting Sweden was discussed above, a focus on a single country in principle delimits the dependability of the results [8]. However, given the purpose of the research presented here, we propose that the consequences are limited, due to the fact that the home page scan also included the investigation on sustainability reports, which were mainly the international sustainability report of the respective companies.

In Study 2, the case study, the cases were selected based on a perception of high achievements in the studied area. This is well in line with the aim to capture a wide image of the studied phenomenon. Credibility [8] refers to how well the presented research reflects reality; the data in the case studies were documented and confirmed by the carefully selected key informants. In this type of research, high dependability (ibid.) is difficult to reach, as the area is in relatively fast transition. However, given the time of the case study, a similar collection procedure would probably have resulted in similar results. An interview guide supported the data collection and is appended as an appendix of this paper. In order to increase the confirmability (ibid.) of the case research and the research at large, presented here, the steps of the different research stages are described above.

The analysis is a joint effort by the researchers involved, which strengthens the quality of the research again through analyst triangulation [43]. Overall, while the specific setting of LSPs and shippers was the focus of this research, the transferability of the results [8] to other LSP–shipper settings than those studied is supposedly high, while the high degree of specificity of the environmental practices makes transferability to other actor constellations relatively low.

3 Frame of reference

The frame of reference takes its starting point in the framework by McKinnon [34] and those seven key parameters that influence the level of CO2 emissions from freight transport. In the remains of this section, the findings from the literature search are related to the different key parameters, and complementary findings from the market perspective are accounted for under the heading Others. Findings from the five papers that came as a result of the systematic literature review [22, 32, 50, 63, 66] are included in the sections below. As the results from the systematic literature search are limited, the frame of reference is further complemented with literature relating to the different areas.

3.1 Modal split

The first parameter that McKinnon [34] mentions is modal split, which describes the extent of mix between transport modes. Modal split is interesting since carbon intensity varies between different modes of transport. Road freight and air freight have relatively high carbon intensity compared to rail and water-borne services. A shift from the former to the latter can decrease carbon emissions from freight transport operations. This is also mentioned by Wu and Dunn [68] and in previous work of McKinnon [33]. Whereas McKinnon [34] writes about lowering CO2 emissions specifically, Wu and Dunn [68] discuss air pollution in more general terms. Despite its potential, it cannot be taken for granted that a modal shift is always beneficiary for the environment; Eng-Larsson and Kohn [14] highlight the importance of considering contextual factors such as demand volatility, performance of transport operator, and logistics systems design (for example centralised or decentralised) in any analysis before making a decision to introduce new transport modes. Closely related to the modal split is the issue of intermodal transports, meaning that various modes of transport are combined. These may, if managed wisely, contribute to decreased environmental impact [48].

Using alternative modes of transportation is mentioned by Weijers et al. [63] as a way for LSPs to achieve their environmental goals. In their investigation of matches and gaps between providers and shippers on the Swedish market, Martinsen and Björklund [32] conclude that there is a gap between the provider’s degree of offering multiple transport modes, and the shippers’ demand. In average, the providers offer alternative modes more often than the average customers demand it.

In the remaining part of this paper, we will refer to the above described environmental practice as: mode choice and intermodal transportation. In accordance with the overview above, this can include either switching from one mode to another, or splitting a transportation operation with the aim to decrease emission or improve the environmental performance of the transportation.

3.2 Handling factor and length of haul

Next, McKinnon [34] mentions average-handling factor and average length of haul. These factors are determined by the logistics system design since they are dependent on the number (average-handling factor) and the mean length (average length of haul) of links in the supply chain. The fact that the logistics system design affects the environmental impact of transports is confirmed by Aronsson and Huge-Brodin [2]. Both average-handling factor and average length of haul can for instance depend on whether the distribution system is centralised or decentralised. A decentralised distribution system requires less transport work and shorter distances between the supply point and the customer and thus, a decentralised distribution system should be beneficial for the environment. However, research indicates that this is not necessarily the case, since centralised systems enable consolidation of goods and changes in transport mode and also reduces the need for emergency deliveries [26]. In addition, a decentralised distribution system means a higher handling factor, which indicates a higher environmental stress [34]. The logistics system design is essential to reach more sustainable solutions, not only in the environmental dimension, but also in terms of social and economic sustainability [40].

Sarkis et al. [50] propose that a wide perspective is needed in the supply chain design. They argue that such a perspective allows for the inclusion of other stakeholders (vendors in their case), since all functions in a supply chain will be affected by the design of products and processes. Furthermore, design of a logistics system should include various ecological themes (ibid.). With regard to logistics system design, Martinsen and Björklund [32] conclude that logistics providers offer logistics system design as part of an environmental offering more often than the average shipper would demand it.

Henceforth, we will refer to the environmental practice described above as logistics system design, which includes both length of haul and handling factor.

3.3 Payload on laden trips and empty running

McKinnon [34] further mentions average payload on laden trips (measured in weight or volume) and proportion of kilometres run empty, which both are directly affected by transport management. Freight consolidation improves vehicle efficiency, which in turn is linked to being environmentally responsible [68]. More specifically, McKinnon [34] states that there is a congruity between higher vehicle fill-rates and a decrease in energy consumption as well as CO2 emissions. Route-planning is one way of managing transports towards increased freight consolidation. Another transport planning issue is the problem of backhaul where trucks have to go back empty after delivery [34, 68]. In general, increased economic transport efficiency often goes hand in hand with environmental improvements [40].

Sarkis et al. [50] provide an example of e-commerce, which addresses the relation between the average payload and transport management. Since Internet sales inevitably include product returns, products need to be taken backwards in the logistics system. By offering to pick up these return products, the LSPs can increase the efficiency of their transportation and distribution systems. This requires efficient planning, and if succeeded, the fill rate of the truck increases and thus the environment benefits through less fuel consumption per tonne-km. This reasoning builds on the precondition that the same logistics operator handles the forward and return transports and also that the total goods volumes within the system increase. Nonetheless, the total goods volumes across the systems are not affected, although hopefully, they would be managed in a more efficient way and thus benefit the environment. Weijers et al. [63] conclude, in line with McKinnon [34], that LSPs mention both improvements on load capacity and avoidance of empty hauls as practices that LSPs use to state their green offerings. The findings of Martinsen and Björklund [32] indicate that LSPs more often consider transport planning as part of an environmental offering, than shippers in average demand it as a green service.

As the literature findings above suggest, increased average payload (or fill-rates) and decreased empty running are possible parts of green logistics services offered by LSPs or required by shippers. In this paper, this environmental practice will be referred to as transport management.

3.4 Energy efficiency

Energy efficiency is another factor mentioned by McKinnon [34] and also by Wu and Dunn [68]. This is the ratio of distance travelled to energy consumed and depends on vehicle characteristics, driving behaviour, and traffic conditions. With regard to vehicle characteristics, McKinnon [34] states that vehicle characteristics show potential for decreased environmental impact. However, although Aronsson and Huge-Brodin [2] also suggest that more energy efficient technology is a way to reduce environmental impact, they mean that this method alone so far has proven insufficient. The EEA [12] also concludes that technology is one way of reducing CO2 emissions, but that this alone will not be able to solve the problem. The potentially decreased environmental impact can be accomplished through for example engine and exhaust systems, aerodynamic profiling, reduction in vehicle tare weight and improved tyre performance [34], which in turn can be triggered by raising legal limits on vehicle weights and sizes [33]. Weijers et al. [63] agree that buying new vehicles that pollute less can be part of LSPs offerings. Martinsen and Björklund [32] conclude that for environmentally classified vehicles there is a possible match between LSPs’ offerings and shippers’ requirements in average.

As mentioned above, driving behaviour is also of relevance to energy efficiency McKinnon [34], and eco-driving is becoming a well-known concept in relation to this (see for example [2]). Weijers et al. [63] conclude that “new driving style” is mentioned by LSPs as a means to reach their environmental goals. This includes training for truck drivers aiming to bring awareness about how gear changing, braking, and speed affect the level of CO2 emissions.

Given the findings from literature about energy efficiency, we suggest two environmental practices that can be a part of a green logistics service as offered by LSPs or required by shippers. Vehicle technology refers to technological aspects of the vehicles, whereas behavioural aspects relate to actions taken by the driver to increase energy efficiency.

3.5 Carbon intensity

The final parameter in the framework by McKinnon [34] for reducing CO2 emissions is carbon intensity of the energy source. The carbon intensity of fuel means the amount of CO2 emissions per unit of energy consumed [34]. One way of lowering the environmental impact of transports is to switch to alternative fuels [68]. Thus, switching to fuel with low carbon intensity results in reduced the environmental impact. McKinnon [34] also emphasises that the energy can be consumed either directly by the vehicle or indirectly at the primary energy source for electrically powered freight operations.

Weijers et al. [63] suggest that an increased use of biofuels can be a part of LSPs practices to reach their environmental goals. Further, Martinsen and Björklund [32] suggest that the shippers’ requirement level regarding alternative fuels matches the LSPs offerings.

In the remaining part of this paper, we will include the carbon intensity of fuels in the environmental practice alternative fuels.

3.6 Others

In addition to the practices above, some other environmental practices emerge from literature as influential on the environmental impact of logistics. These other practices are briefly described below and include environmental management systems, choice of partners, emission data, and efficient buildings.

3.6.1 Environmental management systems

Sarkis et al. [50] suggest that environmental management systems, such as ISO 14000, play an important role in the communication of environmental efforts between actors in a supply chain. Such systems can be related to the minimum performance required [52]. Even though the system is voluntary, it is by many companies used as a requirement for suppliers [39], implying that it would be used as a requirement for LSPs. Such certificates are one way to make the supplier evaluation process more efficient [65]. Companies that are certified may be preferred as partners since the environmental risk associated with these should be lower than that of not certified companies [49]. Also, transport and logistics companies that fail to comply with international standards might even risk a loss in competitive advantage [48]. The investigation by Wolf and Seuring [66] suggests that ISO 14001 certifications of LSPs are welcomed by the shippers, however, not rewarded.

The literature points to that for example ISO 14001 is regarded as a possible, and perhaps important, part of the green logistics service as offered by LSPs and required by shippers. Therefore, environmental managements systems will be included in the subsequent part of this paper as an environmental practice.

3.6.2 Choice of partners

Finding and selecting “green” suppliers is a means to green the supply chain and has by large been facilitated by the Internet and by e-commerce [50]. In relation to selecting suppliers, ISO 14001 is often mentioned in combination with a greening of the supply chain [39, 53]. Green supply chain management may include such factors as who to partner with and how to manage the relationship [49]. Moreover, [49] states that “With the increasing acceptance of ISO 14001 environmental standards, there is a greater role for supply chain management in organisational environment”. From a supply chain management perspective, the logistics provider can be seen one type of supplier (process support rather than product supplier (see [27]). Isaksson and Huge-Brodin [22] take the perspective of the LSP and suggest that also providers make deliberate choices of who to collaborate with regarding environmental aspects. Weijers et al. [63] suggest that award schemes would be a prosperous way to encourage greening practices between LSPs and other stakeholders. Wolf and Seuring [66] describe in their multiple case study, how an LSP’s strong partnerships with shippers may contribute to raise awareness of the economical soundness of improving the environmental performance, which is facilitated through comprehensive collaboration. In that sense, when a potential supplier’s relationship abilities and partner choices presumably matters for the environmental performance of a company, the partner and relationship issue could be part of both the offering and the requirement of green logistics services. We will call this environmental practice choice of partners.

3.6.3 Emission data

Weijers et al. [63] suggest that programmes to enhance the co-operation between LSPs and shippers can include programmes that inform shippers of the CO2 emissions caused by their shipments. According to McKinnon [34], many companies are now auditing their CO2 emissions. At the same time, McKinnon and Piecyk [36] state that there are differing ways of calculating CO2 emissions from road freight and that they give differing results. While the product level can seem attractive when carbon labelling products for customers, it carries many problems related to the correctness of data, assumptions that need to be made, and—not least—the costs associated with this procedure [35]. Additional difficulty arises when trying to measure environmental impact from supply chains including complicated structures and multiple organisations [7, 20]. Lieb and Lieb [30] mention different ways in which logistics companies address the carbon footprint “challenge”: identifying the company footprint, developing a carbon footprint calculator, and developing carbon footprint metrics, all efforts to be prepared to meet potential customer requirements. Wolf and Seuring [66] find that shippers often demand information on their green performance in the form of substantial emission calculations. The investigation by Martinsen and Björklund [32] suggests that there is a substantial difference between LSPs’ offerings of emission data and the shippers’ demands, and that the LSPs overachieve. Further, Wolf and Seuring [66] give an example where a shipper was interested in emission calculations of its freight transports and the LSP was able to offer them this for free at first. As the calculations grew more and more complex, the costs were taken over by the shipper. In the end, the shipper did not want to pay and demanded that the LSP should be charged with the costs. This illustrates how economic concerns offset the environmental interests.

According to the above, emission data appear to be of relevance for the offerings and requirements of green logistics services. Although literature point to a clear focus on CO2 emissions, we will refer to the wider environmental practice emission data in order to be able to allow for other types of emissions as well.

3.6.4 Efficient buildings

Weijers et al. [63] suggest that LSPs’ practices to reduce energy consumption in their warehouses also can be part of their efforts to reach their environmental goals. McKinnon [34] briefly mentions warehouse externalities as included in environmental impact from logistics. Marchant [31] suggests a three-stage framework for assessing the environmental impact of warehousing, including improving energy efficiency in buildings and equipment; harnessing green energy; and design sustainability into buildings. From an LSP perspective, it is relevant to consider not only warehouses, if such services are offered, but also their terminals. Although primarily aimed at warehousing, the framework suggested by Marchant [31] can be applied for buildings in general. We will therefore label this environmental practice efficient buildings, which includes warehouses as well as terminals.

3.7 Summing up the environmental practices

The identified environmental practices are together suggested to capture the content of offerings and requirements relating to logistics and environmental considerations, based on literature. Resulting in ten in total, the environmental practices identified as part of offering or requirements of green logistics services are as follows:

-

Mode choice and intermodal transportation

-

Logistics system design

-

Transport management

-

Vehicle technology

-

Behavioural aspects

-

Alternative fuels

-

Environmental managements systems

-

Choice of partners

-

Emission data

-

Efficient buildings

Although literature in large also address other categories relating to logistics and environmental considerations, we have limited our list to those aspects that directly can be related to companies’ offerings and requirements. Examples of practices that are not included in the ten categories are those that belong to macro level practices [2], such as governmental and legislative practices. Governmental stakeholders can, however, have an impact on those practices that are directly related to offerings and requirements.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Study 1: Home page scan

An overview of the results from the home page scan is shown in Table 4. As can be seen, the home page scan confirms all ten environmental practices identified in the frame of reference. It also provides examples of more specific environmental practices as reflected in LSPs’ offerings and shippers’ requirements on the logistics market. Thus, there does not appear to be any major differences in environmental practices as presented in the general logistics literature (e.g. [34]) and those that are offered and required through home pages on the logistics market. Some identified environmental practices on the home pages fall outside of the pre-defined practices, although they aim at lowering the total environmental stress from logistics, and these are gathered under an “others”-category in Table 4.

The results from the home page scan suggest that some of the ten pre-defined environmental practices found in the literature review are described in more detail by LSP than by shippers (behavioural aspects, vehicle technologies, alternative fuels, environmental management systems, emission data and efficient buildings), whereas others are explained in more detail by shippers that LSPs (mode choice and intermodal transportation, logistics system design, transport management and choice of partners).

Regarding vehicle technologies, the LSPs mention both engine technology and more specifically refrigeration technology while the shippers stay less concrete and generally aim for more environmentally friendly technology. Shippers, on the other hand, also mention low emission tires. With regard to alternative fuels, the LSPs are again more concrete in mentioning electrical, biogas, and hybrid vehicles, while the shippers stay vaguer. This pattern is repeated for environmental management systems, where the LSPs are very specific and the shippers require any standard, emission data, where LSPs describe new tools while the shippers require emission data “at large” as well as for behavioural aspects and efficient buildings.

The remaining four pre-defined practices are described in more detail from the shipper side than from the LSP side. Regarding mode choice and intermodal transportation, the LSPs express in a very general way that intermodal transports are part of their offering in environmental terms, while many of the shippers describe more concretely their ambition regarding specific modes. For the practice logistics system design, the LSPs describe the design of their transport network, while the shippers describe efforts needed to make their logistics system more environmentally friendly. Transport management is described quite sparsely from the LSPs compared to the shippers, who comprise a wide variety of efforts to increase the efficiency of the transports. The pattern that emerges is the opposite from the one described for the first six practices: the shippers appear as more specific as they describe features relating to their system, which in turn creates the demands. The LSPs, on the other hand, need to address the needs of many shippers in providing solutions for a variety of logistics systems.

Finally, among the investigated LSPs, the issue of choosing partners was a non-issue. On the shipper side, we identified one shipper that addressed their suppliers in general, and not LSPs in specific.

Outside the range of the initial practices, two LSPs offer emission offset programmes, where the customers can choose to pay (a low price) for the provider to invest in CO2-reduction programmes of different types. This is a quite explicit offering; however, it does not involve the providers’ business or activities as such. Furthermore, environmental education of the personnel in general, other than eco-driving, is also mentioned. Among the shippers, one additional requirement was identified, which challenged LSPs to adopt a more strategic and long-term view on greening their offerings.

While the home page scan mainly reveals one-sided practices, there are many indications of ongoing cooperation and also of initiatives that demand interaction between LSPs and shippers. A way to further explore this aspect of environmental practices as reflected in offerings and requirements on the logistics market is to take a relation-specific perspective. The results from the case study are therefore presented next.

4.2 Study 2: The case study

The four LSP–shipper relationships that represent the case data provide examples of some of the environmental practices that correspond to the previously described data sets, but also give additional examples of other environmental practices. See Table 5 for an overview. Note that only the environmental practices identified in the cases are included in the table, which is why not all of the practices suggested in the frame of reference are visible.

In the Alltransport–Holmen case, responses from representatives from both companies indicate that environmental consideration is not on the agenda when Holmen buys logistics services from Alltransport. Interestingly, representatives at Alltransport initially said that environmental practices are a part of the relationship between the two companies, but then added that no actual green requirements are put on Alltransport from Holmen. Instead, the results suggest that there is a difference between how Alltransport and Holmen view practices such as high fill-rates and empty running, which Alltransport perceives as environmental practices, most likely in combination with cost savings, while Holmen merely sees cost-saving potential. These two practices are, in accordance with McKinnon [34], part of the general environmental practice transport management that has previously been discussed.

Even though Holmen does not appear to put any environmental requirements on Alltransport, the case study results suggest that Holmen has given environmental issues in the relationship some thought because of a perception that Alltransport is relatively active with regard to environmental work. Still, this is not something that is taken any notice of in the relationship between the two actors, and details about what this environmental work includes are not clear.

The results from the Alltransport–Onninen case indicate that green dimensions are basically not taken into account in the relationship. The transport coordinator at Onninen mentions that the shipper has demands on environmentally high-quality vehicles, which is closely related to the previously identified green practice vehicle technologies. Further, Onninen wants Alltransport to be environmentally certified according to ISO 14001, i.e. have an environmental management system, which is the corresponding general environmental practice. The Alltransport representatives, however, do not mention any environmental demands from Onninen. Similarly to the Alltransport–Holmen case, the findings from the Alltransport–Onninen case also suggest that Onninen are convinced that Alltransport works with environmental issues and that, in addition, Onninen to some extent take environmental practices as given, since they believe them to also decrease Alltransport’s costs.

In contrast to the two cases described above, the results of the DHL–SECO Tools case indicate that environmental practices are an important part of the relationship. In a comparison between SECO Tools and DHL’s other customers, SECO Tools is more environmentally aware than many other companies, according to the key account manager interviewed at DHL. There are several other aspects of the relationship that indicate that environmental practices are important. Emissions data, or more specifically reports of CO 2 emissions, are included in the relationship between DHL and SECO Tools. Furthermore, SECO Tools mentions DHL’s environmental manager as one important aspect of the environmental focus of relationship and that she gives DHL an advantage compared to competitors. This environmental competence of this manager is therefore identified as an additional environmental practice that does not fit into any of the ten initial environmental practices. In this particular relationship, SECO Tools has had extensive communication with the environmental manager, who has helped the shipper learn more about what types of emissions data that is of interest, as well as realistic, to ask for.

In addition, the two people that are primarily responsible for relationship between DHL and SECO Tools have worked with different environmental projects during the last years. One of these projects concerned the shipper’s distribution centre (DC) in Brussels, and the aim was to see whether it was possible to lower the number of trucks that picked up goods from the DC. This resulted in a new pickup system, which can be considered as one part of the general environmental practice transport management.

Finally, although this is not part of the actual relationship between the companies, the GoGreen concept, which is DHL’s emission offset programme, is mentioned by company representatives from both DHL and SECO Tools as a part of DHL’s green offering.

As for the DHL–Ericsson case, the results indicate that environmental issues are of importance in the relationship. The employees interviewed at both DHL and Ericsson appear to be committed to environmental work and both companies emphasise that a decrease in environmental impact also often leads to cost savings. The results from the case provide several suggestions to environmental practices that are a part of the DHL–Ericsson relationship. Ericsson would like DHL to commit to an environmental project every year, and the goal is that the project should benefit both companies. Two examples of such projects are an eco-driving project for a specific route and a milk-round project for the pickup of goods at different Ericsson sites. While the environmental project is an additional environmental practice to the ten practices initially identified, the eco-driving project and the milk-round project fit into the already suggested practices (behavioural aspects and transport management, respectively).

DHL’s emission offset programme—the GoGreen concept—is mentioned by both DHL and Ericsson, but it is not anything that Ericsson is interested in, and the case study results indicate that DHL is aware of this fact. Moreover, emissions data in the form of CO 2 reports are a part of the relationship between DHL and Ericsson. Since there is no standard as to how emissions should be measured, the LSP and shipper have developed a relationship-specific format, according to which the LSP reports emissions every month.

Participation in the Clean Shipping Project is also mentioned by both DHL and Ericsson as an element of their green relationship. The Clean Shipping Project provides an index in which shipping companies can report their environmental impact. This is thus closely related to the general environmental practice vehicle technologies. Finally, the case data indicate that DHL would be capable of taking increased responsibility for the planning of transports, i.e. transport management, for Ericsson, but this is not mentioned by Ericsson as an environmental practice in the relationship.

5 Analysis

The empirical results presented above represents two perspectives of the logistics market; one clear market perspective (Study 1) and one relationship perspective (Study 2). These two different perspectives give two complementary views on how environmental practices are reflected in offerings and requirements on the logistics market. With a starting point in stakeholder theory, this analysis attempts to explain these data sets separately as well as to highlight similarities and discrepancies between them.

Starting with the home page scan, the results suggest that the presentation of environmental practices as part of offerings or requirements on companies’ home pages vary between LSPs and shippers. While LSPs to a larger extent present environmental practices as a part of their offering on their immediate home pages, shippers present environmental practices related to their requirements on specific CSR home pages or in environmental/CSR reports. This might be explained partially by the differing types of stakeholders of LSPs and shipper. The negative environmental impact associated with the transport industry and logistics industry is likely to have an impact on the visibility of the industry which in turn is suggested to have an impact on a company’s stakeholder consideration [17, 47]. With regard to LSPs, several stakeholders have been identified as influencers of LSPs’ environmental practices [21, 30, 34] and home pages could be a way for LSPs to include the interest of several types of stakeholders simultaneously.

In contrast, shippers’ stakeholder interests might not include the environmental practices of LSPs. Instead, focus is likely to be on other environmental (or sustainable) practices, more related to internal operations or in relation to suppliers of physical goods. In relation to this, it could be worth mentioning that LSPs are often perceived as supporting, as opposed to primary, actors of the supply chain [55] and this could be one explanation why shippers do not include environmental practices reflected in LSP requirements on their immediate home pages. Whether this is related to the stakeholder interests of the shippers is beyond the scope of this paper to determine and further research could shed light on stakeholders’ pressure on shippers based on their relationships with LSPs. It could, however, be assumed that shippers’ stakeholders are likely to be more interested in the core activities of the shippers, as opposed to the more peripheral logistics activities conducted by LSPs. Interestingly, the home page scan indicates that companies in logistics intensive industries with consumer products are the most concrete in describing their greening of logistics. According to Rivera-Camino [47], a company’s responsiveness to stakeholder needs is by suggested to be related to its closeness to the final customer. Could it be that companies closer to consumers also perceive more stakeholder pressure to include other aspects of environmental practices than those related to their core businesses? Related to this, Kirchoff et al. [24] suggest that “green consumers” are a growing stakeholder group, which indeed could have an impact on shippers’ home pages in terms of environmental practices related to requirements on LSPs. Further, the fact that the home page scan also indicates that the level of logistics intensity in the shippers’ industries has an impact on the presentation of environmental practices related to LSPs could imply that such industries have different stakeholder pressures than those with lower logistics intensity. More research is needed in order to illuminate how stakeholders of different shipper industries have impact on the shippers’ requirements on LSPs with regard to environmental practices.

As discussed above, the home pages are considered as a form of mass communication, striving to reach a wide variety of stakeholders. Still, the presence of examples and arguments on specific environmental practices was far richer on the LSPs’ home pages than on the shippers’. One explanation can be the relation of green logistics practices to the core business of the respective company types. However, drawing on Kirchoff et al. [24] and Post et al. [45], another explanation can lie in the distinction between primary and secondary stakeholders. In our setting, the shippers would belong to the primary stakeholders of the LSPs, why the arguments directed towards the potential customers (i.e. the shippers) are many. On the other hand, the LSPs would only be secondary stakeholders to the shippers, whose primary stakeholders would include their customers. Building on the argument that the home page information is directed to many various stakeholders, but some stakeholders would be more important than others, the shippers probably attempt to satisfy the information needs of their customers in the first place.

As opposed to the home page scan, the case study takes a clear relationship perspective and includes four specific LSP–shipper relationships. A consequence of this perspective is that, more clearly than in the home page scan, there is one main stakeholder for the LSP or shipper in the relationship. That is, in the Alltransport–Holmen relationship, for example, Holmen’s stakeholder of main relevance is Alltransport and vice versa. Taking a stakeholder view, it appears as though the environmental practices included in the various relationships to a large extent are based on the shippers’ requirements on the LSPs. As Table 5 shows, two of the LSP–shipper relationships include more environmental practices than do the other two. As implied by the empirical data, in those cases where the shippers are fairly uninterested in environmental practices, there few environmental practices are required by the shippers. This appears to be the situation for Alltransport–Holmen as well as for Alltransport–Onninen. When the shipper does not have any requirements in terms of environmental practices, the offerings from the LSPs do not appear to get much attention. In the two other cases (DHL–SECO Tools and DHL–Ericsson), the shippers are seemingly more interested in their environmental impact from logistics and, possibly as a result, there are more environmental practices included in these relationships. One explanation for these results could lie in a potential power advantage of the shipper over the LSP and thus making the shippers one of the three types of stakeholders suggested by Mitchell et al. [37]. Previous research has proposed that large customers have power to influence their suppliers in terms of environmental practices [25, 59]. The results of this research implies that both large and small shippers, relatively to the LSPs (see Table 3), have the potential to influence the LSPs.

In terms of the environmental practices identified as reflected in the offerings and requirements in these specific relationships, most of them fall into the initial ten categories of environmental practices identified in the frame of reference and confirmed by the home page scan (see Table 5). However, some of the practices within the pre-defined ten categories appear to be more specific than many of those identified on the home pages. Two examples are the change in pickup system and the milk-run project that fit into transport management. These environmental practices appear to be a result of the specific relationship and thus differ somewhat from those practices presented on LSPs’ or shippers’ home pages. Further, the cases offer additional environmental practices to the ten suggested in the frame of reference. Emission offset programmes (or the GoGreen concept) were identified in the home page scan as well. Interestingly, the cases confirm these offset programmes as belonging to the more general logistics market, since none of the shippers studied appear interested in including this environmental practice in their relationships with the LSP. In contrast, environmental competence at the LSP and environmental project appear to be of relevance in LSP–shipper relationships. Unlike emission offsets, these practices give more insight into the types of practices that can be reflected as parts of offerings and requirements in specific LSP-shipper relationships.

Given the reasoning above, it appears as though when the shipper is relatively uninterested in requiring environmental practices, the potential environmental practices are fairly standard and are much like those practices reflected in the offerings and requirements on the home pages. When shippers do require environmental practice, on the other hand, the potential of more relationship-specific practices appears to increase. Again, this points to the shipper as a strong stakeholder in LSP–shipper relationships in relations to environmental practices.

The analysis presented above has attempted to explain how environmental practices are reflected in the offerings and requirements on the logistics market. The stakeholder perspective taken has enabled the identification of several differences between the two sets of empirical data studied for this paper. In the next section, these discrepancies are taken one step further as a classification of the environmental practices is suggested.

5.1 Classification of environmental practices

While the literature findings to a large extent relate to actions that can be taken in order to lower the environmental impact from logistics, the home page scan to a large extent contributes with environmental practices that are vital for companies to show to stakeholders of various types. However, the home page scan also gave indications of cooperative practices between LSPs and shippers and the cases then further contribute to illustrate such practices. Notably, the cases as well as some indications in the home page scan include practices that are of importance as a type of precondition that determines whether the business deal between the LSP and shipper will come about. Further, the case results also point to more cooperative environmental practices that can be conducted during the ongoing relationships. Based on the combined findings from the literature, the home page scan, and the cases, we suggest a classification of environmental practices based on their role in the business between LSPs and shippers. Specifically, the suggested categories are as follows:

-

1.

Environmental practices that can be expressed as offerings or requirements prior to a business deal;

-

2.

Environmental practices that can be applied as precondition for a contract; and

-

3.

Environmental practices that can be included in ongoing relationships between LSPs and shippers.

Figure 2 illustrates these different roles in the LSP–shipper relationships. While some practices can be identified in all three categories, some are only present in one or two of them. The following sections go through the logic that has led to the classification. The starting point for the analysis is the ten general environmental practices and the additional environmental practices suggested by the home page scan and the cases.

5.1.1 The general environmental practices

Similarly to the literature about green logistics, the technical and more transport-related practices are quite well covered on the home pages, by both LSPs and shippers. More specifically, the general environmental practices mode choice and intermodal transports, vehicle technologies, fuels, efficient buildings as well as behavioural aspects are identified from the home pages, indicating that these practices are important to show to stakeholders visiting the pages. They can therefore be viewed as potential parts of offerings from LSPs or requirements from shippers, placing them in category number 1 in Fig. 2. In addition, one shipper in the home page scan clearly stated that LSPs were required to both comply with engine class requirements and with requirements for driver training for fuel-efficient driving, which suggests that the practices fuels and behavioural aspects also fall into category 2. As the home pages are directed towards a diversity of stakeholders, it is interesting to note that also contractually related arguments are used. In particular, it is interesting that the shippers state their supplier requirements on their home pages, whereas suppliers according to Kirchoff et al. [24] as well as Post et al. [45] are not primary stakeholders. This can be explained whether the shippers’ customers actually are supposed to care for how their provider of goods manages its supply chain, including the transport and logistics providers.

Vehicle technologies are in the Alltransport–Onninen case included as high-quality vehicles, which appears to be a precondition for the business deal. Similarly, participation in the clean shipping project was requirement from Ericsson in the contracting phase with DHL. Based on these findings, it is suggested that vehicle technologies can be a precondition for the business deal (category 2), whereas this environmental practice does not appear as important in the continued relationship between LSPs and shippers. As for behavioural aspects, the eco-driving project identified in the DHL–Ericsson case was a result of the LSP’s environmental initiative during the ongoing relationship. No evidence is found that this was a precondition in the negotiation process, which on the other hand, the environmental project that led to the eco-driving project was. Because of this, the additional environmental practice environmental project appears as a precondition for the business deal (category 2), which in turn leads to other projects, such as the eco-driving example, in the ongoing relationship (category 3). The examples from the cases to a higher degree span more specific practices than those expressed on the home pages. This is natural, provided that the home pages are actually directed towards a wide scope of stakeholders; the definitions of the practices thus have to be more general in order to be understood by actors with different perspectives (cf. [18]).

In relation to transport management, this environmental practice is, together with logistics system design, two of the least mentioned practices on the home pages, in particular from the LSP side. This implies that while they can be used as offerings or requirements, they are often more difficult to present in a comprehensive way on a home page with respect to their specificity. This could also be related to the complexity of the two practices; they are likely to be more difficult to communicate on a home page than for example vehicle technologies or fuels. In line with the reasoning above, home pages are supposedly directed towards a range of different stakeholders holding a wide variety of expertise on the specific green logistics topic. Hence, it would only be logic to refrain from more complex descriptions on the generally directed home pages in favour of the more straightforward of the green logistics practices. Further, transport management is an environmental practice that is often expected by shippers even without the involvement of the environmental aspect of the requirements since it is believed to be a prerequisite for efficient and cost-saving operations of the LSPs [40]. Nonetheless, these two environmental practices are placed in the first category in Fig. 2 to illustrate that some companies include them in their offers and requirements prior to the business deal. Looking at the cases, transport management is noted as an environmental practice in three of them, while logistics system design is not mentioned as practices conducted in the ongoing relationships.

Interesting to note is, however, the DHL–SECO Tools relationship; there were ongoing discussions within the scope of logistics system design. Because of the fact that the discussions had not resulted in actual practices within this practice, this was not part of the case description given earlier in this paper. The DHL–SECO Tools case does, however, point to that logistics system design can be a part of the ongoing relationship. It is even likely that in order for this environmental practice to result in some changes, it needs to be included in the ongoing relationship. Logistics system design is therefore added to category 3, but marked with an asterisk in order to illustrate that it was not a result of an actual environmental practice found in the cases.

The practices identified within transport management can both belong to category 2 and 3 in Fig. 2. In the case of Alltransport–Holmen, high fill-rates appear to be a precondition for the business deal, even though the actual work to keep fill-rates high for natural reasons also needs to be conducted during the ongoing interaction. The other two examples of transport management, i.e. the change in pickup system in the DHL–SECO Tools case and the milk-round project in the DHL–Ericsson case, are examples of transport management during the ongoing relationships (category 3). Similarly to the eco-driving project described in relation to behavioural aspects, the milk-round project is a result of the environmental project included in the contract phase in the DHL–Ericsson relationship.

Environmental management systems are often used as a requirement for suppliers in general [39, 52]. The case results point to that this can also be true for requirements of LSPs and environmental management systems are therefore placed in category 2. Further, the results from the home page scan indicate that this environmental practice is of importance also in the offerings or requirements prior to the business deal (category 1). Environmental management systems is also an example of a practice that is not specific for green logistics—rather it is something that can be required by any supplier of goods and services, which also supports its presence on the home pages directed towards a range of stakeholders.

With regard to emission data, most of the examples from the home page scan and the cases deal with CO2 emissions, which is perhaps not so surprising given the present focus in general as well as within the field of environmental logistics [34]. While the home page scan points to that emissions data are an important part of the offers and requirements as such (category 1), the two DHL cases point to that they can also be a precondition for the business deal (category 2) as well as include additional initiatives during the ongoing relationships (category 3). More specifically, in the DHL–Ericsson relationship, the two companies have adjusted the CO2 reports to fit their relationship.