Abstract

Education beyond traditional ages for schooling is an important source of human capital acquisition among adult women. Welfare reform, which began in the early 1990s and culminated in the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act in 1996, promoted work rather than education acquisition for this group. Exploiting variation in welfare reform across states and over time and using relevant comparison groups, we undertake a comprehensive study of the effects of welfare reform on adult women’s education acquisition. We first estimate effects of welfare reform on high school drop-out of teenage girls, both to improve upon past research on this issue and to explore compositional changes that may be relevant for our primary analyses of the effects of welfare reform on education acquisition among adult women. We find that welfare reform significantly reduced the probability that teens from disadvantaged families dropped out of high school, by about 15%. We then estimate the effects of welfare reform on adult women's school enrollment and conduct numerous specification checks, investigate compositional selection and policy endogeneity, explore lagged effects, stratify by TANF work incentives and education policies, consider alternative comparison groups, and explore the mediating role of work. We find robust and convincing evidence that welfare reform significantly decreased the probability of college enrollment among adult women at risk of welfare receipt, by at least 20%. It also appears to have decreased the probability of high school enrollment among this group, on the same order of magnitude. Future research is needed to determine the extent to which this behavioral change translates to future economic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although welfare reform is often dated to the landmark 1996 PRWORA legislation, reforms actually started taking place in the early 1990s when the Clinton Administration greatly expanded the use and scope of “welfare waivers” to allow states to carry out experimental or pilot changes to their AFDC programs, with random assignment required for evaluation. Waivers were approved in 43 states, ranging from modest demonstration projects to broad-based statewide changes, and constituted the first phase of welfare reform. Many policies and features of state waivers were later incorporated into PRWORA.

Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives, “Overview of Entitlement Programs” for 1994 and 1998 (Green Books). Available at:

http://aspe.hhs.gov/94gb/sec10.txt and http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=105_green_book&docid=f:wm007_07.105.

Our time span ends in 2001 to minimize the potential of introducing confounding differential trends from events that occurred long after the last set of states implemented TANF in 1997 (CA on January 1, 1998) such as the 2001 recession and the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. As a sensitivity check, investigating through 2000 or 2005 did not materially change the results (available upon request).

For instance, the indicator for Maryland, which enacted a major waiver on March 1, 1996, is coded as 0.667 for 1996 to reflect the 8 months that the waiver was in place for that year (using October as the reference month, since the analyses are based on the October CPS). 29 states enacted such waivers, across various months, between 1992 and 1996.

States enacted TANF differentially throughout 1996 and 1997, with California being the last state to implement on January 1, 1998. Information on state implementation of major AFDC waivers and TANF is obtained from the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: http://aspe.hhs.gov/HSP/Waiver-Policies99/policy_CEA.htm.

The data can be found at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ofa/caseload/caseloadindex.htm.

The data can be found from the Education Commission of the States’ Clearinghouse Notes, “Compulsory School Age Requirements,” March 1992, March 1994, March 1997, and 2005, and from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d04/tables/dt04_148.asp

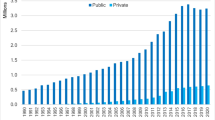

Changes in welfare caseloads are not due solely to welfare policy. Research suggests that much of the drop in caseloads, especially prior to TANF implementation in 1996, was not policy-related. While the welfare caseload fell dramatically in the 1990s, only part of the decline (≤50%) was due to welfare reform legislation (Blank 2002). Changes in economic conditions and other factors also played an important role.

For parsimony, Eq. 1 imposes the restriction that, within states, the effects of the non-welfare reform measures (vectors X, Z, Year and State*t) are similar for the target and comparison groups. We test this assumption based on the likelihood ratio test, and are unable to reject the null hypothesis that the restriction is valid in virtually all of the main specifications. As a robustness check, we also estimated models which allow the effects of X and Z, and Year, to differ across target and comparison groups. Coefficient magnitudes are not materially affected, though standard errors are inflated somewhat due to reduced degrees of freedom.

It is possible that some teens and young adults may have left home by the time they are 20. To avoid possible sample selection issues, we include all unmarried youth living in non-two parent households. In additional analyses, not shown, we include only individuals who live with one parent. In these additional analyses, results are very similar to those shown in Table 2. As an alternative, we also narrow the age range to 15 to 19; results remain robust with respect to both magnitudes and significance.

For all sample restrictions, unmarried is defined as widowed, divorced, separated, never married, or other non-married; for married, the spouse can be present or absent.

We specifically exclude women who are 19 and 20 years of age from this analysis of older adult women, since some of those young adults may have repeated a grade or enrolled in school at a later age and therefore still be in the process of completing high school. We also estimate models that include 19 and 20 year old women to gauge the sensitivity of our results to the age cut-off.

We omit women between the ages of 21–23 when analyzing college enrollment, as women in that age range may still be in college and erroneously counted as low-educated and at-risk of being on welfare. We explore alternative age restrictions before inferences are drawn.

Only three states implemented major AFDC waivers in 1992, and they all did so relatively late in the year: CA in December, and MI and NJ in October. We exclude these three states from the reported 1992 means.

Specifically, we estimate models for all outcomes based on a limited sample that is restricted to pre-reform observations (AFDC Waiver = 0 and TANF = 0), defining reform as the implementation of major waivers to AFDC or the implementation of TANF, whichever occurred first. With the reference category being the year prior to reform, coefficients on the interactions between the various years pre-reform and the target indicator show differences in trends between the target and comparison groups relative to the year of reform. All of these trend differences are individually and jointly insignificant (p-value on the joint F-statistic ranges from 0.132 to 0.882) in all models for all sets of target and comparison groups.

Standard errors also remain robust to clustering at the state-year level and do not affect inferences

The legal drop-out age ranged from 14 to 18 between 1992 and 2001 and was not constant within states over this period. Four states (CA, MN, MS, and NV) and DC increased the maximum school attendance age over the sample period.

In additional specifications, we included all young women, regardless of their state’s compulsory schooling age. The effect of TANF was halved and became statistically insignificant. This is validating of our results, and is consistent with a zero effect of welfare reform on those required to be in school due to compulsory schooling laws, averaged with a negative effect of welfare reform on those who have the legal option of dropping out.

Since policy variation is at the state-year level, reduced sample sizes lead to small numbers of observations per each state-year cell, thereby adding noise to cell means, inflating standard errors, and leading to imprecise estimates.

This is not surprising since the DDD specification, with a valid comparison group, already nets out the impact of omitted state-specific time-variant factors. The robustness is validating, though, with respect to the appropriateness of the comparison group.

The results are robust to alternative upper and lower age cut-offs, up to +/− 1 year for the lower age cut-off and up to +/− 4 years for the upper age cut-off. Stratifying by age (24–35 versus 36–49), the absolute and relative magnitude of the impact of welfare reform are expectedly larger for younger women since the prevalence of high school and college enrollment generally declines with age. For instance, welfare reform reduced college enrollment among low-educated women ages 24–35 by between 14% and 32%, compared to 10–21% among older women. Similar relative patterns hold for the other schooling measures, across younger and older adult women.

Alternately, we also confirm that the welfare reform policy variables do not significantly predict inclusion in the analysis sample or inclusion in the target group versus comparison group. When we regress an indicator for our analysis sample (target or comparison group relative to all others) or an indicator for the target group on our policy measures and the control variables, marginal effects on AFDC Waiver and TANF were insignificant with close-to-zero magnitudes, suggesting that selection into our samples is not systematically affected by welfare reform.

This may be because the majority of states had experimented with AFDC waivers prior to PRWORA, and therefore the sample restriction (to women who are at least 21 years of age when their state implemented welfare reform) would be more binding for later years of the CPS for these states.

While college completion may also be affected by welfare reform policies, selection on this basis is less material for two reasons. First, at any point in time, college graduates are at lower risk of being on welfare. Second, the question of how welfare reform affects school enrollment is by definition a question that relates to only a selected group—low-educated women who are at an elevated risk of public assistance. It is not meant to generalize to, and would not be relevant for, women with a college degree or above.

We are not aware of any prior research that has addressed this potential source of selection, perhaps because scant attention has been paid to the potential effects of welfare reform on educational attainment of adults.

Results are not sensitive to alternate lag structures.

We also estimate difference-in-differences (DD, as opposed to DDD) models to ascertain that the effects are primarily driven through responses by individuals in the target group, by restricting the sample to only these individuals. No comparison group is utilized, and the DD effect is identified only through variation in the timing and incidence of welfare reform across states. While standard errors inflate and render some of the estimates statistically insignificant, the effect magnitudes remain highly similar to those reported in the DDD specifications, suggesting that welfare reform reduced school enrollment among low-educated single mothers by between 14% and 19% (results not shown).

The only real change is that some of the standard errors for the TANF effects are inflated rendering some of these effects statistically insignificant. However, the coefficient magnitudes remain stable. The loss of precision is due to the limited variation in TANF implementation combined with the loss in degrees of freedom with the inclusion of the Year*Target indicators. Magnitudes and standard errors for AFDC Waivers, which have substantial variation across states over time, are not affected.

Specifically, we examined these policies at two points in time (1999 and 2002), and designated states as “strict” if they did not allow education as a stand-alone activity and they did not allow schooling to be combined with other work activities for more than 1 year. Twenty-two states (AZ, CO, CT, FL, ID, IN, KS, LA, MA, MD, MI, MS, ND, NM, NY, OH, OK, OR, SD, TX, WA, WI) and D.C. fall into this category. The data, available on the State Policy Documentation Project website, can be found at: http://www.spdp.org/tanf/postsecondary.PDF and http://clasp.org/publications/postsec_table_i_061902.pdf

The education policy and work incentives measures are based on TANF and not AFDC waivers. Ideally, these detailed state measures would reflect both phases of welfare reform. Unfortunately, uniform data on education policy and work incentives under AFDC waivers are not available. That said, the relevant TANF provisions are likely reflective of the general sentiment in a state toward work versus education.

Estimating an alternate specification that controls for continuous hours worked and its quadratic term leads to an inflection in the hours worked—school enrollment relationship at about 19 to 20 h. Thus, the dichotomous indicators for hours worked are defined to account for this inflection and to control for a non-parametric non-linear relationship.

All specifications reported in Table 7 control for interactions between the target indicator and the labor supply measures. The marginal effects of hours worked and household income reported in the table refer to those for the target group. In order to be concise, marginal effects of hours and income are not reported for the comparison group. Generally, the negative link between hours worked and school enrollment is stronger for the target group, and the income effect on school enrollment tends to be positive for the comparison group.

Excluding household income does not significantly increase the magnitudes of the marginal effects, suggesting that the attenuation of the effect is mostly due to the effects of work.

The CPS is not suitable for studying the effects of welfare reform on vocational education and training due to the way that type of education is elicited in the surveys—as current (as opposed to past year) attendance at a school other than a college for a vocational course. As a result, we found that the surveys drastically under-represent vocational education and training compared to the gold-standard national figures from the NHES.

References

Becker GS (1975) Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Bitler MP, Gelbach JB, Hoynes HW (2005) Welfare reform and health. J Hum Resour 40(2):309–334

Blank RM (2002) Evaluating welfare reform in the United States. J Econ Lit 40(4):1105–1166

Blank RM (2007) What we know, what we don’t know, and what we need to know about welfare reform. National Poverty Center Working Paper Series #07-19, http://www.http://npc.umich.edu/publications/u/working_paper07-19.pdf

Blank RM, Schmidt L (2001) Work, wages, and welfare. In: Blank RM, Haskins (eds) The new world of welfare. Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C

Boudett KP, Murnane RJ, Willett JB (2000) “Second-chance” strategies for women who drop out of school. Mon Labor Rev 123(12):19–31

Bound J, Lovenheim MF, Turner S (2010) Why have college completion rates declined? An analysis of changing student preparation and collegiate resources. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 2(3):129–157

Corman H (1983) Postsecondary education enrollment responses by recent high school graduates and older adults. J Hum Resour 18(2):247–267

Dave DM, Reichman NE, Corman H, Dhiman D (2011) Effects of welfare reform on vocational education and training. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper #16659. NBER, Cambridge, MA

Dee TS, Jacob BA (2007) Do high school exit exams influence educational attainment or labor market performance? In: Gamoran A (ed) Standards-based reform and children in poverty: lessons for “no child left behind”. Brookings Institution Press, Washington DC, pp 154–200

DeLeire T, Levine J, Levy H (2006) Is welfare reform responsible for low-skilled women’s declining health insurance coverage in the 1990s? J Hum Resour 41(3):495–528

Eissa N, Hoynes HW (2006) Behavioral responses to taxes: lessons from the EITC and labor supply. Tax Pol Econ 20:73–110

Gennetian LA, Knox V (2003) Staying single: the effects of welfare reform policies on marriage and cohabitation. MDRC, New York

Grogger J (2004) Time limits and welfare use. J Hum Resour 39(2):405–424

Grogger J, Karoly LA (2005) Welfare reform: effects of a decade of change. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Hao L, Cherlin AJ (2004) Welfare reform and teenage pregnancy, childbirth, and school drop-out. J Marriage Fam 66(1):179–194

Hotz VJ, Imbens GW, Klerman JA (2006) Evaluating the differential effects of alternative welfare-to-work training components: a reanalysis of the California GAIN program. J Labor Econ 24(3):521–566

Jacobs JA, Winslow S (2003) Welfare reform and enrollment in postsecondary education. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 586:194–217

Kaestner R, Tarlov E (2006) Changes in the welfare caseload and the health of low-educated mothers. J Pol Anal Manag 25(3):623–643

Kaestner R, Korenman S, O’Neill J (2003) Has welfare reform changed teenage behaviors? J Pol Anal Manag 22(2):225–248

Kane T, Rouse CB (1999) The community college: training students at the margin between college and work. J Econ Perspect 13(1):63–84

Koball H (2007) Living arrangements and school drop-out among minor mothers following welfare reform. Soc Sci Q 88(5):1374–1391

Kodde D (1986) Uncertainty and the demand for education. Rev Econ Stat 68:460–467

Leigh DE, Gill AM (1997) Labor market returns to community colleges: evidence for returning adults. J Hum Resour 32(2):334–353

London RA (2006) The role of postsecondary education in welfare recipients’ paths to self-sufficiency. J High Educ 77(3):472–498

Moffitt RA (1992) Incentive effects of the U.S. welfare system: a review. J Econ Lit 30(1):1–61

Moffitt RA (1995) Report to congress on out-of-wedlock childbearing. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Hyattsville

Moffitt RA (1998) The effects of welfare on marriage and fertility. In: Moffitt RA (ed) Welfare, the family, and reproductive behavior: research perspectives. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, pp 50–97

O’Donnell K (2006) Adult education participation in 2004-05 (NCES 2006-077). U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics, Washington, DC

Offner P (2005) Welfare reform and teenage girls. Soc Sci Q 86(2):306–322

Peters EH, Plotnick RD, Jeong S (2003) How will welfare reform affect childbearing and family structure decisions? In: Gordon RA, Walberg HJ (eds) Changing welfare. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, pp 59–91

Price C (2005) Reforming welfare reform postsecondary education policy: two state case studies in political culture, organizing, and advocacy. J Sociol Soc Welfare 32(3):81–106

Ratcliffe C, McKernan S, Rosenberg E (2002) Welfare reform, living arrangements, and economic well-being: a synthesis of literature. The Urban Institute, Washington, DC

Schoeni RF, Blank RM (2000) What has welfare reform accomplished? Impacts on welfare participation, employment, income, poverty, and family structure. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper #7627

Shaw KM, Goldrick-Rab S, Mazzeo C, Jacobs JA (2006) Putting poor people to work: how the work-first idea eroded college access for the poor. Russell Sage, New York

U.S. Census Bureau Census 2000 (2000) PHC-T-39. Table 5: school enrollment of the population 3 years and over by age, nativity, and type of school: http://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/briefs/phc-t39/tables/tab5S-03.xls [Accessed October 18, 2008]

U.S. Census Bureau (2002) Work and work-related activities of mothers receiving temporary assistance to needy families: 1996, 1998, and 2000. Current Population Reports, 70–85

U.S. Census Bureau (2005) Table 12: employment status and enrollment in vocational courses for the population 15 years old and over, by sex, age, educational attainment, college enrollment, race, and Hispanic origin: http://www.americanfactfinder.biz/population/socdemo/school/cps2005/tab12-01.xls [Accessed October 18, 2008]

U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey (2006) Table A-6: age distribution of college students 14 years old and over, by sex: October 1947 to 2006. http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/school/TableA-6.xls [Accessed October 18, 2008]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1997) Office of the assistant secretary for planning and evaluation. Setting the baseline: a report on state welfare waivers, available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/isp/waiver2/title.htm [Accessed April 3, 2009]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2000) Characteristics and financial circumstances of TANF recipients, fiscal year 1999. Administration for Children and Families. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ofa/character/FY99/analysis.htm [Accessed October 18, 2008]

Ziliak JP (2006) Taxes, transfers, and the labor supply of single mothers. Unpublished working paper Available at: http://www.nber.org/~confer/2006/URCf06/ziliak.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This project was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant number R01HD060318. The authors are grateful for valuable research assistance from Oliver Joszt, Natasha Pilkauskas and Afshin Zilanawala; for helpful comments from Suzanne Clain, Julie Hotchkiss, Robert Kaestner and the participants at the University of Illinois at Chicago Department of Economics seminar series, Sanders Korenman; and for helpful information on welfare policies vis-à-vis education from Julie Strawn and Elizabeth Lower-Basch, as well as Gilbert Crouse and Don Oellerich of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dave, D.M., Corman, H. & Reichman, N.E. Effects of Welfare Reform on Education Acquisition of Adult Women. J Labor Res 33, 251–282 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-012-9130-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-012-9130-4