Abstract

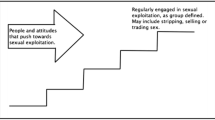

This article juxtaposes the results of descriptive and inferential statistical analysis, derived from 125 client case files at a Denver transitional housing facility for women leaving the sex industry, with the results of a content analysis that examined how all 34 similar U.S. facilities represent themselves, their clients, and their services on their websites. Content analysis results ascertained four primary findings with respect to transitional housing facilities for women leaving the sex industry, including their conflation of sex trading with sex trafficking, dominance by Christian faith-based organizations, race-neutral approach, and depiction of their clients as uneducated and socially isolated. Yet our statistical analysis revealed that significant differences exist between women’s sex industry experiences in ways that are strongly determined by ethno-racial identity, age, marital status, and exposure to abuse throughout the life course. Juxtaposing the results of these analyses highlights some rather glaring disconnects between the ways that facility websites depict their clients and the meaningful differences between women seeking services at the Denver transitional housing facility. These findings raise significant concerns regarding approaches that ignore ethno-racial differences, collapse the sex industry’s complexity, make assumptions about the women’s educational or other needs, and neglect the importance of women’s community and relational ties. Taken together, these troubling realities suggest a need for evidenced-based, rather than ideology-based, alternatives for women who wish to leave the sex industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The 34 organizations the research team located using this method are: Amirah (Wenham, MA), Arbor (Charlottesville, VA), Aspire (New York, NY), Created Women (Tampa, FL), Dawn’s Place Residence (Las Vegas, NV), Destiny House (Las Vegas, NV) Eden House (New Orleans, LA), Esther House (Denver, CO), Generate Hope (San Diego, CA), Hope House (Baton Rouge, LA), LifeWay Network Safe Housing (New York, NY), Magdalene House (Nashville, TN, St. Louis, MO. & Charleston, SC), Magdalene KC (Kansas City, Kansas), Mariposa House (Denver, CO), New Life for Women (Chicago, IL), P.R.E.S.S. On/Extraordinary Living (Springfield, IL), Purchased: Not for Sale (Shreveport, LA), Refuge for Women (Lexington, KY), Refuge for Women- Las Vegas (Las Vegas, NV), Renewed Hope House/Independent Living Program (Atlanta, GA), Restore NYC Safehome (New York, NY), RockStarr Ministries Safe House (Orem, UT), Safe House San Francisco (San Francisco, CA), Samaritan Women (Baltimore, MD), Selah Freedom (Sarasota, FL), Sparrow House (Houston, TX), Street’s Hope (Denver, CO), The Dream Center Human Trafficking Program (Los Angeles, CA), The Homestead (Manhattan, KS), The Monarch (San Francisco, CA), The Sanctuary (Orlando, FL), The Well House (Leeds, AL).

The team did not receive results by searching the combinations of those key terms along with the words “diversion,” “court,” “feminist,” “pornography,” and “escort(ing).”

Admittedly, a more nuanced insight into agencies’ understandings of their clients may be found in speaking with program staff or systematically investigating their portfolio of promotional materials, both of which are potentially fruitful areas for future research.

One transitional housing facility did link to their interfaith efforts involving Protestant Christian organizations and a Rabbi associated with a synagogue.

The research team opted to use the word “pimp” in quotes because of its widespread cultural salience among both street-involved women and the dominant culture in which they and many readers of this article both live; nonetheless, the co-authors of this paper remain troubled by the lack of scholarly and popular cultural attention paid to the racialized connotations of this word.

References

Abel, G., Fitzgerald, L., Healy, C., & Taylor, A. (2010). Taking the crime out of sex work: New Zealand sex workers’ fight for decriminalization. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Agustín, L. (2007). Sex at the margins: Migration, labour markets, and the sex industry. London: Zed.

Aidala, A., Cross, J., Harre, D., & Sumartojo, E. (2005). Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: Implications for prevention and policy. AIDS and Behavior, 9(3), 251–265.

Bernstein, E. (2007). The sexual politics of the “New Abolitionism”. Differences, 18(3), 128–151.

Bourgois, P., Prince, B., & Moss, A. (2004). The everyday violence of hepatitis C among young women who inject drugs in San Francisco. Human Organization, 63(3), 253–264.

Brewer, D., Dudek, J., Potterat, J., Muth, S., Roberts, J., & Woodhouse, D. (2006). Extent, trends, and perpetrators of prostitution-related homicide in the United States. Journal of Forensic Science, 51, 1101–1108.

Bumiller, K. (2008). In an abusive state: How neoliberalism appropriated the feminist movement against sexual violence. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Caputo, G. (2008). Out in the storm: Drug-addicted women living as shoplifters and sex workers. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Census Bureau. (2010). The Black population: 2010. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2011/dec/c2010br-06.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2016.

Clarke, R., Clarke, E., Roe-Sepowitz, D., & Fey, R. (2012). Age of entry into prostitution: Relationship to drug use, race, suicide, education level, childhood abuse, and family experience. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 22, 270–289.

Comte, J. (2014). Decriminalization of sex work: Feminist discourses in light of research. Sexuality and Culture, 18, 196–217.

Crago, A. (2008). Our lives matter: Sex workers unite for health and human rights. New York: Open Society Institute.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299.

Csete, J., & Cohen, J. (2010). Health benefits of legal services for criminalized populations: The case of people who use drugs, sex workers and sexual and gender minorities. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 38(4), 816–831.

Cusick, L. (2006). Widening the harm reduction agenda: From drug use to sex work. International Journal of Drug Policy, 17, 3–11.

Cusick, L., & Hickman, M. (2005). “Trapping” in drug use and sex work careers. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 12, 369–379.

Dalla, R. (2006). “You can’t hustle all your life”: An exploratory investigation of the exit process among street-level prostituted women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 276–290.

Dewey, S. (2017). Women of the street: How the criminal justice-social services alliance fails women in prostitution. New York: New York University Press.

Duff, P., Deering, K., Tyndall, M., Gibson, K., & Shannon, K. (2011). Homelessness among a cohort of women in street-based sex work: The need for safer environment interventions. BMC Public Health, 11, 643–650.

Dworkin, A. (1993). Prostitution and male supremacy. Michigan Journal of Gender & Law, 1, 1–12.

Edwards, J., Halpern, C., & Wechsberg, W. (2006). Correlates of exchanging sex for drugs or money among women who use crack cocaine. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18(5), 420–429.

Farley, M. (2004). “Bad for the body, bad for the heart”: Prostitution harms women even if legalized or decriminalized. Violence Against Women, 10(10), 1087–1125.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2013). Crime in the United States. https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2013/crime-in-the-u.s.-2013/tables/table-43. Accessed February 23, 2016.

Golder, S., & Logan, T. (2007). Correlates and predictors of women’s sex trading over time among a sample of out-of-treatment drug abusers. AIDS and Behavior, 11, 628–640.

Haaken, J., & Yragui, N. (2003). Going underground: Conflicting perspectives on domestic violence shelter practices. Feminism & Psychology, 13, 49–71.

Jasinski, J., Wesely, J., Wright, J., & Mustaine, E. (2010). Hard lives, mean streets: Violence in the lives of homeless women. Chicago: Northeastern University Press.

Krüsi, A., Chettiar, J., Ridgway, A., Abbott, J., Strathdee, S., & Shannon, K. (2012). Negotiating safety and sexual risk reduction with clients in unsanctioned safer indoor sex work environments: A qualitative study. American Journal of Public Health, 102(6), 1154–1159.

Kurtz, S., Surratt, H., Kiley, M., & Inciardi, J. (2005). Barriers to health and social services for street- based sex workers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 16(2), 345–361.

Lazarus, L., Chettiar, J., Deering, K., Nabess, R., & Shannon, K. (2011). Risky health environments: Women sex workers’ struggles to find safe, secure and non-exploitative housing in Canada’s poorest postal code. Social Science and Medicine, 73, 1600–1607.

Leigh, C. (1997). Inventing sex work. In J. Nagle (Ed.), Whores and other feminists (pp. 225–231). New York: Routledge.

Lopez-Embury, S., & Sanders, T. (2009). Sex workers, labour rights, and unionization. In T. Sanders, M. O’Neill, & J. Pitcher (Eds.), Prostitution: Sex work, policy and politics (pp. 94–110). London: Sage.

MacKinnon, C. (2007). Are women human? And other international dialogues. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Majic, S. (2013). Sex work politics: From protest to service provision. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Miller, M., & Neaigus, A. (2002). An economy of risk: Resource acquisition strategies of inner city women who use drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 13, 409–418.

Oselin, S., & Weitzer, R. (2013). Organizations working on behalf of prostitutes: An analysis of goals, practices, and strategies. Sexualities, 16(3–4), 445–466.

Quinet, K. (2011). Prostitutes as victims of serial homicide: Trends and case characteristics, 1970-2009. Homicide Studies, 15, 74–100.

Raphael, J., & Shapiro, D. (2004). Violence in indoor and outdoor prostitution venues. Violence Against Women, 10, 126–239.

Rekart, M. (2005). Sex-work harm reduction. Lancet, 366(9503), 2123–2134.

Rhodes, T. (2002). The “risk environment”: A framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy, 20, 193–201.

Rhodes, T., Wagner, K., Strathdee, S., Shannon, K., Davidson, P., & Bourgois, P. (2012). Structural violence and structural vulnerability within the risk environment: Theoretical and methodological perspectives for a social epidemiology of HIV risk among injection drug users and sex workers. In P. O’Campo & J. Dunn (Eds.), Rethinking social epidemiology: Towards a science of change (pp. 205–230). New York: Springer.

Richie, B. (2000). A Black feminist reflection on the anti-violence movement. Signs, 25, 1133–1137.

Romero-Daza, N. (2003). “Nobody gives a damn if I live or die:” Violence, drugs and street-level prostitution in inner city Hartford, Connecticut. Medical Anthropology, 22, 233–259.

Salfati, C., James, A., & Ferguson, L. (2008). Prostitute homicides: A descriptive study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 505–543.

Sallmann, J. (2010). “Going hand-in-hand”: Connections between women’s prostitution and substance use. Journal Of Social Work Practice In The Addictions, 10(2), 115–138.

Semple, S., Strathdee, S., Zians, J., & Patterson, T. (2011). Correlates of trading sex for methamphetamine in a sample of HIV-negative heterosexual methamphetamine users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(2), 79–88.

Sered, S., & Norton-Hawk, M. (2008). Disrupted lives, fragmented care: Illness experiences of criminalized women. Women and Health, 48(1), 43–61.

Sered, S., & Norton-Hawk, M. (2013). Criminalized women and the health care system: The case for continuity of services. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 19(3), 164–177.

Singer, M. (1996). A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 24(2), 99–110.

Singer, M. (2006). A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS, Part 2: Further conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 34(1), 39–51.

Thukral, J., & Ditmore, M. (2003). Revolving door: An analysis of street-based prostitution in New York City. New York: Sex Workers Project at the Urban Justice Center.

Weitzer, R. (2010). The mythology of prostitution: Advocacy research and public policy. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7, 15–29.

Wies, J. (2008). Professionalizing human services: A case of domestic violence shelter advocates. Human Organization, 67(2), 221–233.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

This study did not receive funding, and all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dewey, S., Hankel, J. & Brown, K. Transitional Housing Facilities for Women Leaving the Sex Industry: Informed by Evidence or Ideology?. Sexuality & Culture 21, 74–95 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-016-9379-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-016-9379-5