Abstract

Religious commitment is associated with decreased sexual activity, poor sexual satisfaction, and sexual guilt, particularly among women. The purpose of this paper was to investigate how religious commitment is related to sexual self-esteem among women. Participants included 196 female undergraduate students, 87 % of whom identified as Christian. Participants completed the Sexual Self-Esteem Inventory for Women (SSEI-W), Religious Commitment Inventory-10, Revised Religious Fundamentalism Scale, Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale, and a measure of their perception of God’s view of sex. Results suggested that women with high religious commitment held more conservative sexual attitudes. Significant relationships between religious commitment and two subscales (moral judgment and attractiveness) of the SSEI-W revealed that women with high religious commitment were less likely to perceive sex as congruent with their moral values and simultaneously reported significantly greater confidence in their sexual attractiveness. A significant relationship between religious commitment and overall sexual self-esteem was found for women whose religion of origin was Catholicism, such that those with higher religious commitment reported lower sexual self-esteem. A hierarchical regression analysis revealed that high religious commitment and perception that God viewed sex negatively independently predicted lower sexual self-esteem, as related to moral judgment. Implications of the findings are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Because sexual messages are often communicated through religious institutions or religious authorities (Hunt and Jung 2009), religious commitment may have an impact on the manner in which people perceive themselves sexually. As messages about sex and sexuality vary greatly within and between faiths (Browning et al. 2006), these sexual self-perceptions likely differ based on the religion with which one was raised and/or currently identifies, as well as the degree of religious commitment to which one adheres. While some benefits of the impact of religion on sexuality have been observed, given both the history of Christian denominations’ prescriptions regarding sex for women (Runkel 1998) as well as higher rates of religiosity among women and prevalence of Christianity in the United States (U.S.) (Pew Research Center 2015), it is possible that U.S. women’s sexuality may be especially adversely affected by level of religious commitment.

To date, most of the research related to sex and religious commitment has been in the context of exploring the relationship between religious beliefs and sexual attitudes and behaviors in adolescent populations (Buzwell and Rosenthal 1996; Edwards et al. 2008; Leonard and Scott-Jones 2010; Luquis et al. 2012; Penhollow et al. 2005, 2007; Zaleski and Schiaffino 2000). However, little is known about how religion impacts sexual self-esteem, or the ways in which adult women subjectively experience their sexuality (Mayers et al. 2003). The current study sought to explore how and to what degree religious commitment impacted sexual self-esteem in a sample of undergraduate women.

In an early meta-analysis of gender differences pertaining to sexuality, Oliver and Hyde (1993) found that women reported less sexual permissiveness, more anxiety and guilt related to sex, less frequent sex, and fewer sexual partners compared to men. Women are more likely to endorse the idea that premarital sex is more acceptable for men than women (Oliver and Hyde 1993). More recently, Petersen and Hyde (2011) found that gender differences in sexual behaviors and attitudes between men and women are often due in part to social expectations for women to be more conservative sexually as well as strict regulations within certain societies or institutions. Allen and Brooks (2012) found young college women were much more likely compared to their male peers to retain their childhood religious beliefs and were particularly conflicted about the message that sex outside of marriage was wrong. Once married or in long-term committed relationships, women reported greater emotional and physical satisfaction with sex than women in relationships they expect to end (Waite and Joyner 2001). Therefore, the impact of conservative sexual messages on religious women may be impacted by partnership status.

Despite the patriarchal nature of most major world religions (Browning et al. 2006; Hunt and Jung 2009), research indicates that women are more religious than men (Pew Research Center 2015). Exploring sex differences in perceptions of sex, Bonds-Raacke and Raacke (2011) found women more often noted religion as a means by which they dealt with stress and more frequently engaged with religious media, such as television or radio shows. Compared to men, women simultaneously report higher religiosity and lower sexual permissiveness (Brelsford et al. 2011) and increased sexual constraints (Cochran and Beeghley 1991).

Sexual Self-Esteem

For the current investigation, we used Mayers et al.’s (2003) definition of sexual self-esteem as a conceptualization of sexual self which may include evaluations of sexual orientation, but also includes evaluations of one’s sexual appeal, competence, sexual behaviors, and/or value as a sexual being. In developing a measure, Zeanah and Schwarz (1996) found sexual self-esteem was comprised of five domains: the ability to enjoy sex with a partner (skill/experience); personal appraisal of attractiveness to a partner (attractiveness); perception of agency in sexual acts and managing sexual thoughts and feelings (control); the congruence of sexual thoughts, feelings, and behaviors with personal moral standards (moral judgment); and congruence of sexual behavior with personal aspirations (adaptiveness). Some authors have referred to the construct of sexual self-esteem as sexual self-concept; accordingly, we have retained the original term chosen by the authors of their respective studies. High sexual self-esteem has been correlated with more positive sexual experiences and relationships. In a 4-year longitudinal study, positive sexual esteem among young adolescent women was associated with a steady increase in sexual openness and a decrease in anxiety associated with sex over time. This openness and decreased anxiety led to more frequent participation in sex that, in turn, allowed young women to gain confidence and further bolster a positive sexual self-concept (Hensel et al. 2011).

Researchers have shown that positive sexual self-esteem is also associated with increased sexual satisfaction (Impett and Tolman 2006), frequent sexual communication (Oattes and Offman 2007), and safe sexual practices (Breakwell and Millward 1997; Lou et al. 2010). To date, much of the research on sexual self-esteem has primarily been centered on the experiences of adolescents and sexual self-esteem’s impact on adolescents’ sexual risk-taking behaviors. Research exists to suggest both a positive and negative relationship between sexual self-esteem and sexual risk-taking. Research that has found a relationship between increased religious commitment and an inhibition in sexual behaviors may contribute to the perception of sexual behaviors among adolescents as negative and dangerous experiences, rather than natural and positive parts of human development (O’Sullivan et al. 2006).

Based on a study conducted with undergraduate students, Winter (1988) found that sexual self-concept correlated positively with contraceptive use and higher sexual self-concept was associated with use of more effective contraceptive measures. Rostosky et al. (2008) identified a path from sexual risk-taking knowledge to sexual self-efficacy mediated by sexual self-esteem such that those with higher levels of sexual self-esteem reported higher levels of sexual self-efficacy. As a result, adolescents with positive views of their sexual selves appear more likely to make responsible decisions regarding their sexual health (Rostosky et al. 2008).

While some research supports the benefits of positive sexual self-esteem, other studies note that it may increase sexual risk-taking, although risk-taking has often been inadequately operationalized. Breakwell and Millward (1997), for example, found a relationship between sexual responsibility and increased contraceptive use in a sample of adolescent women. Buzwell and Rosenthal (1996) noted that adolescents categorized as sexually competent, sexually adventurous, or sexually driven were engaging in greater sexual risk-taking behaviors than those who were sexually naïve or unassured. Though high risk behaviors included those that involved an unsafe exchange of bodily fluids that may result in STIs, other behaviors described as risky may not as clearly result in problematic outcomes when sex is managed responsibly. For example, some authors have labeled as risky an increased number of partners; some sexual activities, such as oral sex; casual sex (Buzwell and Rosenthal 1996); and frequent sexual activity (Breakwell and Millward 1997). Similarly and problematically, Pai et al. (2012) found a negative relationship between sexual self-concept and sexual risk with sexual risk defined not only as engagement in unprotected sex but also as a failure to delay dating and failure to avoid sexual harassment (Pai et al. 2012), which tends to pathologize normal adolescent behavior and may misattribute responsibility to those who experience sexual harassment. We caution that although some research suggests that positive sexual self-esteem may encourage sexual experimentation, the increased frequency of sex, number of sexual partners, or engagement in sexual behaviors may not necessarily be indicative of unsafe sexual practices.

Sexual Attitudes

Sexual attitudes refer to the ways in which individuals think and feel about multiple dimensions of sex and sexuality, such as premarital sex or homosexuality. Often, these attitudes are linked to one’s behaviors, as sexual behaviors may be driven by more emotional components such as attitudes (Hendrick et al. 2006). Therefore, sexual attitudes may inform sexual self-esteem, but they are a distinct construct that includes both specific and broad attitudes about sex. Sexual permissiveness in particular may contribute to women’s perceptions of themselves as sexual beings. Kimberly et al. (2013) found strong, negative relationships between sexual attitudes, including permissiveness, and religious commitment, such that higher sexual attitude scores predicted lower levels of religious commitment.

Studies of the relationship between sexual attitudes and religious commitment suggest that religious individuals’ sexual attitudes are more conservative (Kimberly et al. 2013; Lefkowitz et al. 2004). Religious women have been shown to lack desire for casual sex (Njus and Bane 2009) and oppose types of sex that are not procreative, including masturbation (Davidson et al. 2004). When religious women engage in non-procreative sexual behaviors, they report increased sexual guilt (Cowden and Bradshaw 2007; Davidson et al. 1995).

Women attending church more regularly have greater levels of guilt related to petting, initial sexual experience, and current sexual behavior. Women also reported more negative perceptions of non-procreative sexual activities, such as oral-genital sex and anal intercourse (Davidson et al. 2004). This guilt may be more salient for women who perceive sex as contradicting religious teachings more frequently than men. Research exploring sex differences in sexual attitudes among religious individuals found that 41 % of men but no women endorsed intercourse as an acceptable behavior at the beginning of a relationship. In the context of a dating relationship, 47 % of religious men and just 18 % of religious women endorsed sexual intercourse as an acceptable practice (Leonard and Scott-Jones 2010).

While the relationship between sexual attitudes and religious commitment has been explored, to the authors’ knowledge, the relationship between sexual attitudes and sexual self-esteem among women has not yet been explored. Given that conservative sexual attitudes limit the types of sexual behaviors women perceive as appropriate and likely limit those in which they engage, and religious women experience guilt related to their sexual behaviors, less permissive views of sex may negatively impact women’s sexual self-esteem.

Sex and Level of Religious Commitment

Religious commitment is measured in a variety of ways such as assessing one’s beliefs, church or religious service attendance, and internal experiences (Hill and Hood 1999). Although slight differences in definition may exist, terms such as religiosity, religiousness, and religious commitment are often used interchangeably in the literature. Fundamentalism is an aspect of religiousness that refers to the degree to which one is extreme in his or her adherence to a particular faith (Ysseldyk et al. 2010) and perceives that faith to be the only true set of religious teachings (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 2004).

Similar to studies of sexual self-esteem, studies related to sex and religious commitment often explore the relationship between religious commitment and adolescents’ sexual behaviors. Research suggests that higher levels of religious commitment are associated with fewer sexual partners (Barken 2006), abstinence (Edwards et al. 2008; Luquis et al. 2012), and decreased hooking up behavior (Penhollow et al. 2007). High religious commitment’s ability to delay sex is often framed as beneficial. However, little is known about women’s experiences of their sexual selves, in the context of their religion, once they become sexually active.

Exploring the relationship between religiosity and sexual behavior in college students, Penhollow et al. (2005) found those reporting less frequent church attendance and fewer religious feelings were more likely to engage in a variety of sexual behaviors. In a study of Mexican adolescents, Catholic girls reported having engaged in first intercourse later than Catholic boys and nonreligious adolescents. Greater church attendance and consideration of religious values when making decisions about sex predicted greater endorsement of the importance of female virginity (Espinosa-Hernandez et al. 2015). Owen et al. (2011) found no significant impact of religiosity on frequency of hooking up after controlling for other factors such as alcohol use and depressive symptoms. Some research has demonstrated that benefits of religiosity among adolescents, such as decreased number of sexual partners, may not exist in in the Black community (Barken 2006). Though a great deal of data exists to support level of religious commitment as a deterrent of risky sexual behavior among adolescents, it may be overgeneralized and fail to consider possible covariates such as family structure (Miller et al. 2001) and sex education (Lindberg and Maddow-Zimet 2012).

Zaleski and Schiaffino (2000) found that religious individuals, whether extrinsically or intrinsically oriented, engaged in less sexual activity. Similarly, religiousness appears to reduce harmful health-related behaviors including engagement by girls and women in sexual behaviors while abusing substances (Toussaint 2009). However, studies of religion and sex, particularly among adolescents, often define safe sex as abstinence or infrequent sexual activity (Breakwell and Millward 1997; Buzwell and Rosenthal 1996). Zaleski and Schiaffino (2000) found adolescents with high religious identification who were sexually active reported less frequent condom use. Ahrold et al. (2011) found similar negative attitudes toward condom use in those who were fundamentally religious.

Lefkowitz et al. (2004) found decreased sexual activity among emerging adults with higher levels of religiosity. More religious participants were also more likely to perceive condoms and condom use negatively and question the ability of condoms to prevent pregnancy and STIs (Lefkowitz et al. 2004). Indeed, Davidson et al. (2004) observed more religious young women were less likely to plan sexual experiences and use condoms when participating in oral-genital sex. However, as adolescents age and become involved in relationships they describe as committed, they are more likely to engage in sex despite level of religious commitment (Leonard and Scott-Jones 2010). Therefore, although more religious adolescents may be abstinent, negative perceptions of contraception may become dangerous as they age and enter adulthood and become more sexually active.

Studies have shown that religiosity may be associated with deleterious effects on one’s sexual satisfaction. In a sample of unmarried older adults, McFarland et al. (2011) found that more religious individuals were less likely to engage in sexual activity, a relationship stronger in women. Interestingly, among the married sample, religiosity was not related, as hypothesized, with greater frequency of sex or sexual satisfaction regardless of the level of happiness in the marriage. Thus, in this study religiosity was not predictive of an improved sex life, but did predict decreased sexual activity among unmarried individuals (McFarland et al. 2011). Rowatt and Schmitt (2003) found that individuals with intrinsic religious motivation, those who internalize religious teachings and values, were more sexually restricted and desired less sexual variety than those with extrinsic religious motivation, those who engage in religious activities in order to gain benefits such as community but adhere minimally to religious teachings. Intrinsically religious and fundamentally religious women also report lower frequency of sexual fantasy (Ahrold et al. 2011). In a study of sexual fantasy experiences among conservative Christians, participants reported their behavior as morally unacceptable and engaging in sexual fantasizing provoked guilt and anxiety (Gil 1990). These findings suggest potentially decreased sexual satisfaction among religious women.

Perception of God’s View of Sex

Research suggests that one’s attitudes about sex are shaped by religious beliefs and messages from within the religious community. In order to relieve distress associated with discrepancies between one’s faith and sexual practice, some gay Christians find peace with their identities by providing alternative interpretations for biblical texts that have traditionally been used to condemn them (Yip 2005). Clinicians are encouraged to make those in faith-based communities aware of positive depictions of sex and sexuality present in the bible (Haffner 2004). Therefore, the interpretation of religious texts may play a significant role in determining perceptions of others’ sexual behavior.

In a study of religiosity and sexual behavior in college students, a negative relationship was found between God’s positive view of sex and giving oral sex within the previous month, sexual intercourse within the previous month, and any participation in anal sex. However, these results were only significant for men. Generally, women who abstained from sexual intercourse had very low scores on the measure of God’s positive view of sex (Penhollow et al. 2005).

Given that one’s interpretation of religious messages about sex impacts sexual behavior, perception of God’s view of sex may impact the sexual self-esteem of women and was included as a variable in the current investigation.

Rationale for Current Study

Hunt and Jung (2009) asserted that religion often serves as the gatekeeper of what is deemed acceptable sexual practice. Most of the major world religions are situated within patriarchy, a system linked with the history of oppression of women (Miller 2013). In consideration of this patriarchal structure, religious standards and expectations around sex are typically particularly restrictive for women (Hunt and Jung 2009). For women, traditional Christian religious views have often equated sex with reproductive purposes contained within heterosexual marriage, ignoring sensual gratification (Jantzen 2005). Even within heterosexual marriage, women may struggle with sexual fulfillment as women’s sexual pleasure is often devalued by the Christian church and only procreative, penile-vaginal sex is prescribed (Jung 2005). Although some Christians adhere to a more progressive interpretation of their faith, with 70.6 % of people in the Unites States identifying as Christian (Pew Research Center 2015), a significant number of U.S. women have likely experienced restrictive messages regarding sex.

Most studies of religious commitment and sex are conducted with adolescent samples in the context of sexual risk-taking. Although there is increasing interest in sex-positivity, researchers more typically pursue scholarship focused on more deleterious consequences of sex (Arakawa et al. 2013). Likewise, studies of sex and religion often focus on the dangers of sex and the ability of religious commitment to reduce participation in risky sexual behaviors (Barken 2006; Edwards et al. 2008; Luquis et al. 2012; Penhollow et al. 2007). While some studies have explored the harmful role religious commitment may play in sexual satisfaction (McFarland et al. 2011; Rowatt and Schmitt 2003), sexual fantasy (Ahrold et al. 2011; Gil 1990), and safe sex practices (Davidson et al. 2004; Lefkowitz et al. 2004), to the authors’ knowledge, there have been no published studies exploring the relationship among religious commitment, fundamentalism, and sexual self-esteem in adult women, a gap we intend to fill with the current investigation.

Hypotheses

As religion informs what is considered sexually appropriate and has traditionally been less permissive of sexual behavior for women (Hunt and Jung 2009; Jantzen 2005; Jung 2005; Miller 2013), the purpose of the current study was to explore the relationship between women’s religious commitment, religious fundamentalism, sexual self-concept, sexual attitudes, and perception of God’s view of sex. As a relationship between religiosity and negative perceptions of sexual behavior has been established previously, we hypothesized that these perceptions would impact how women perceive themselves sexually. Based on the extant research, we generated the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 1: Women with higher religious commitment will have less sexually permissive attitudes compared to women with low religious commitment.

-

Hypothesis 2: Women with higher religious commitment will have lower sexual self-esteem as compared to women with low religious commitment. This hypothesis also predicted lower scores for all dimensions of sexual self-esteem (perceived skill/experience, attractiveness, control, moral judgment, and adaptiveness) for women with greater religious commitment compared to women with lower religious commitment.

-

Hypothesis 3: Women with higher levels of religious fundamentalism will have lower sexual self-esteem as compared to women with low religious fundamentalism. This hypothesis also predicted lower scores for all dimensions of sexual self-esteem (perceived skill/experience, attractiveness, control, moral judgment, and adaptiveness) for women with high levels of religious fundamentalism as compared to women with lower levels of religious fundamentalism.

-

Hypothesis 4: Women with less permissive sexual attitudes will have lower sexual self-esteem as compared to women with more permissive sexual attitudes. This hypothesis also predicted lower scores for all dimensions of sexual self-esteem (perceived skill/experience, attractiveness, control, moral judgment, and adaptiveness) for women with less permissive sexual attitudes as compared to women with more open and permissive sexual attitudes.

-

Hypothesis 5: If religious commitment predicts sexual self-esteem, the relationship will be moderated by perception of God’s view of sex, such that women with high levels of religious commitment whom believe God views sex positively will have higher sexual self-esteem than those who believe God views sex negatively. This hypothesis also predicted that religious commitment’s relationship to all dimensions of sexual self-esteem (skill/experience, attractiveness, control, moral judgment, and adaptiveness) would be moderated by perception of God’s view of sex.

Method

Participants

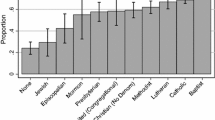

Female undergraduate college students (n = 207) from a mid-sized public university primarily for women in the United States Southwest were recruited via the university’s SONA experiment management system. Eleven participants were not included in the study due to duplicate entries or incomplete data for a final total of 196 participants. Participants were currently enrolled in undergraduate level psychology courses and voluntarily participated in this study in order to earn required research credit for their courses. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 51 years (M = 20.05, SD = 4.6). The sample was diverse in ethnicity with 30.6 % of participants identifying as White, 24.5 % as Hispanic or Latina, 24.5 % as Black, 15.3 % as Asian American or Pacific Islander, and 5.1 % as bi/multiracial or other. Participants were predominantly heterosexual (93.4 %) and in their first year at the university (61.2 %). Most participants identified their religion of origin (87.2 %) and/or current religion as Christian (81.6 %), or a Christian denomination including Protestant and Catholic (Table 1). Sexually active participants accounted for 56.6 % of the sample, while 43.4 % of participants reported they were abstinent.

Instruments

Participants completed five questionnaires including the author-generated demographics questionnaire, the Sexual Self-Esteem Inventory for Women (Zeanah and Schwarz 1996), the Religious Commitment Inventory-10 (Worthington et al. 2003), the Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale (Hendrick et al. 2006), the Revised Religious Fundamentalism Scale (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 2004), and the Perception of God’s View of Sex Scales (Penhollow et al. 2005).

Demographics

A 7-item demographics questionnaire was administered to identify participants’ age, sex, ethnicity, religion of origin (the religion in which one was raised), current religious preference, sexual orientation, and current level of sexual activity (sexually active or abstinent).

Sexual Self-Esteem Inventory for Women

The Sexual Self-Esteem Inventory for Women (SSEI-W) is a self-report measure of women’s overall sexual self-concept or perception of sexual self (Zeanah and Schwarz 1996). The scale consists of 81 items answered in Likert format wherein (1) indicates “strongly disagree” and (6) indicates “strongly agree.” Higher scores indicate greater sexual self-concept. Reliability and validity studies were performed on a sample of traditionally college-aged women, aged 18–22 (n = 327). They were predominantly White (90 %) and Catholic (66 %) or Protestant (20 %). In initial testing, the scale demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .97). The measure is composed of five subscales related to one’s self-perception including sexual functioning: skill and experience, attractiveness, control, moral judgment, and adaptiveness. Items include statements such as “I feel I am pretty good at sex” and “I have no regrets about the things I have done sexually” (Zeanah and Schwarz 1996). The current study demonstrated an alpha of .96.

Religious Commitment Inventory-10

The Religious Commitment Inventory-10 (RCI-10) was utilized to measure the integration of religion into daily activities and the degree to which one views the world through religious schemas (Worthington et al. 2003). The measure is a 10-item inventory answered in Likert format wherein (1) indicates “not at all true of me” and (5) indicates “totally true of me.” Higher scores indicate greater levels of religious commitment. The inventory was validated on a sample of undergraduate students (n = 155). In initial testing, the measure demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .93) and 3-week test–retest reliability, r(155) = .87. Internal consistency (α = .88) and test–retest reliability, r (121) = .84, remained moderately high to high in a sample of Christian undergraduates (Worthington et al. 2003). The RCI-10 includes intrapersonal and interpersonal subscales measuring aspects of religious commitment. Items include statements such as “I spend time trying to grow in understanding of my faith” and “I enjoy working in the activities of my religious organization.” The current study demonstrated an alpha of .94.

Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale

The Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale (BSAS) measures attitudes about sex by evaluating multiple dimensions (Hendrick et al. 2006). The scale consists of 4 subscales: permissiveness, birth control, communion, and instrumentality. For the purposes of this research, only the permissiveness subscale, measuring the extent to which a person perceives sex as an informal act, was utilized. The permissiveness subscale consists of 10 items to which respondents responded with level of agreement in a Likert format in which (A) indicates “strongly agree with statement” and (E) indicates “strongly disagree with the statement.” The BSAS demonstrated moderate to high internal consistency: permissiveness (α = .95). Items include statements such as “casual sex is acceptable” and “it is okay for sex to be just good physical release” (Hendrick et al. 2006). The current study demonstrated an alpha of .91.

Revised Religious Fundamentalism Scale

The Revised Religious Fundamentalism Scale (RFS-R) measures the perception of one’s religion as the only set of religious teachings containing the fundamental truth about human existence and God and allowing for a special relationship with a deity (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 2004). The RFS-R includes 12 statements to which respondents may answer (−4) “very strongly disagree” to (+4) “very strongly agree,” with (0) representing a neutral response. Items include statements such as “to lead the best, most meaningful life, one must belong to the one, fundamentally true religion” and “God has given humanity a complete, unfailing guide to happiness and salvation, which must be totally followed.” The current study demonstrated an alpha of .90.

Perception of God’s View of Sex Scale (PGS)

The items related to perception of God’s view of sex measures the degree to which one believes God has positive or negative views regarding sexual acts. The scale consists of 6 items to which participants may respond (1) “strongly agree” to (5) “strongly disagree,” with (3) representing “undecided.” In a sample of college students, the items demonstrated adequate internal consistency: negative items (α = .73) and positive items (α = .64). Items include statements such as “God intended sex to be only for procreation” and “sexuality is a gift of God and as such should be enjoyed” (Penhollow et al. 2005). The current study demonstrated alphas of .76 and .68 for negative and positive items, respectively.

Results

The first hypothesis predicted that women with higher religious commitment would have more conservative sexual attitudes compared to women with low religious commitment. As predicted by Hypothesis 1, religious commitment was significantly negatively correlated with sexual permissiveness, r = −.35, p < .01. This finding indicates that more religious women were less likely to view sex as an informal act and were less likely to see casual sex as acceptable. In an exploratory analysis comparing sexually active women to abstinent women, religious commitment only correlated significantly with sexual permissiveness for abstinent women, r = −.27, p < .05, such that more religious, abstinent women held more conservative sexual attitudes.

The second hypothesis predicted that women with higher religious commitment would have lower overall sexual self-esteem compared to women with less religious commitment. Religious commitment was not significantly correlated with overall sexual self-esteem r = −.05, n.s. Correlations were also calculated for the five subscales of the SSEI-W. Religious commitment showed significant correlations with the subscales of moral judgment and attractiveness, a marginally significant correlation with the adaptiveness subscale, and no significant correlation with the subscales of control and skill/experience.

Religious commitment significantly negatively correlated with the moral judgment subscale of the SSEI-W, r = −.25, p < .01, which suggests that religious women were less likely to perceive their sexual behaviors and feelings as acceptable and congruent with their own moral standards. Religious commitment and adaptiveness displayed a marginally significant negative correlation, r = −.13, p = .06. This finding suggests that religious women are less likely to be pleased with the role sex plays in their lives and less likely to perceive sex as congruent with their personal aspirations. Although not predicted, results revealed religious commitment was significantly positively correlated with sexual attractiveness, r = .22, p < .01. This finding suggests that religious women were more likely than less religious women to be proud of their bodies and appraise their own sexual attractiveness positively. Religious commitment was not significantly correlated with skill/experience, r = −.07, n.s., nor control, r = −.06, n.s. but showed a non-significant trend in the predicted direction. These findings indicate partial support for Hypothesis 2.

The third hypothesis predicted that women with higher levels of religious fundamentalism would have lower sexual self-esteem as compared to women with low levels of religious fundamentalism. It also predicted women with higher levels of religious fundamentalism would have lower scores on SSEI-W subscales of skill/experience, attractiveness, control, moral judgment, and adaptiveness. Religious fundamentalism was not significantly correlated with overall sexual self-esteem, r = −.04, n.s. Correlations were also calculated for the five subscales of the SSEI-W. Religious fundamentalism showed significant correlations with three subscales (moral judgment, adaptiveness, and attractiveness). No significant correlations were found between religious fundamentalism and the two remaining subscales (control and skill/experience). Religious fundamentalism was significantly negatively correlated with both the moral judgment, r = −.28, p < .01, and adaptiveness, r = −.14, p < .01, subscales of the SSEI-W. This finding suggests that fundamentally religious women are less likely to perceive their sexual behaviors and feelings as acceptable and congruent with their own moral standards. Additionally, fundamentally religious women are less likely to value sex as a part of their lives and less likely to perceive sex to be congruent with their personal aspirations. Religious fundamentalism was not significantly correlated with skill/experience, r = −.01, n.s., or control, r = .00, n.s. Although not predicted, findings revealed religious fundamentalism was significantly positively correlated with the sexual attractiveness, r = .19, p < .01. This result suggests that fundamentally religious women were more likely to be proud of their bodies and appraise their own sexual attractiveness positively. In an exploratory analysis, increased religious commitment was associated with positive self-evaluations of sexual attractiveness for both sexually active, r = .22, p < .05, and abstinent women, r = .27, p < .05. However, religious fundamentalism was only significantly related to sexual attractiveness for sexually active women, r = .21, p < .05. Religious fundamentalism was not significantly associated with positive self-evaluations of sexual attractiveness for abstinent women, r = .20, n.s.

The fourth hypothesis predicted that women with less sexually permissive attitudes would have lower overall sexual self-esteem compared to women with more sexually permissive attitudes. It also predicted women with less sexually permissive attitudes would have lower scores on the subscales of skill/experience, attractiveness, control, moral judgment, and adaptiveness. Sexual self-esteem was not significantly correlated with sexual permissiveness (as measured by the BSAS), r = −.07, n.s. Correlations were also calculated for the five subscales of the SSEI-W. Sexually permissive attitudes were significantly correlated with one subscale (control), marginally significantly correlated with one subscale (moral judgment). Sexual permissiveness was not significantly correlated with the three remaining subscales (skill/experience, adaptiveness, and attractiveness). Sexual permissiveness was also not significantly correlated with skill/experience, r = −.08, n.s., attractiveness, r = −.12, n.s., or adaptiveness, r = −.03, n.s., subscales of the SSEI-W. Although not initially predicted, sexual permissiveness displayed a marginally significant positive correlation with the moral judgment scale of the SSEI-W, r = .14, p = .06. This finding suggests that sexually permissive women are more likely to experience their sexual behaviors as consistent with their moral values. Also contrary to predictions, sexually permissive attitudes were significantly negatively correlated with the control subscale of the SSEI-W, r = −.17, p < .05. This finding suggests that women with sexually permissive attitudes were less likely to feel agency and control over their sexual acts, thoughts, and feelings. Women with sexually permissive attitudes were less likely to know what they wanted sexually and would be less likely to communicate what they wanted sexually to a partner (Table 2).

An exploratory analysis was performed to examine relationships between variables by religion of origin and current religion. Religious commitment was significantly negatively correlated with sexual self-esteem, r = −.28, p. < .05 for those participants whose religion of origin was Catholic (n = 58), suggesting that religious women raised Catholic had poorer perceptions of their sexual selves than less religious women raised in the Catholic faith. Sexual permissiveness was significantly negatively correlated with sexual self-esteem, r = −.40, p. < .05, but only for participants who reported their current religion was Protestant. This suggests that women who identify as Protestant and who endorse sexually permissive attitudes have poorer perceptions of their sexual selves than Protestant women with less sexually permissive attitudes (Table 3).

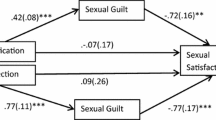

To test the fifth hypothesis that perceptions of God’s view of sex serves a moderating variable for the relationship between religious commitment and sexual self-esteem, we conducted a hierarchical multiple regression analysis. As religious commitment was only significantly correlated with the moral judgment subscale of the SSEI-W, the relationship between religious commitment, perception of God’s view of sex, and the moral judgment subscale of the SSEI-W were examined. The overall model was significant, R 2 = .08, F(3, 195) = 5.78, p. < .01. In the first step two variables were included: religious commitment and perception of God’s view of sex. These variables accounted for 8 % of the total variance in sexual self-esteem, R2 = F(2, 195) = 8.40, p. < .001. Both religious commitment and perception of God’s view of sex were significant independent predictors of the moral judgment subscale of the SSEI-W. This finding suggests that religious commitment and perception of God’s view of sex account for a small but statistically significant amount of the variance in women’s belief that their sexual behaviors are congruent with their morals. Religious women were less likely to view their sexual behaviors and feelings as acceptable, b = −.21, t(195) = −3.02, p < .01. Although not predicted, women who perceived God as viewing sex negatively were more confident in the congruence between their sexual behaviors and morals, b = .14, t(195) = 2.01, p < .05. The interaction term between religious commitment and perception of God’s view of sex was added in the second step. It did not significantly add to the amount of variance in sexual self-esteem; therefore, perception of God’s view of sex does not appear to serve as a moderator of the relationship between religious commitment and the moral judgment subscale of the SSEI-W.

Discussion

Consistent with previous research (Ahrold et al. 2011; Davidson et al. 2004; Kimberly et al. 2013; Lefkowitz et al. 2004; Njus and Bane 2009; Uecker 2008), religious commitment was related to more conservative sexual attitudes in the current study. Additionally, religious women were less likely to perceive their sexual behaviors as congruent with their moral standards. As most of the sample identified as Christian, this finding seems cogent given the sex-negative messages often communicated by Christian organizations and authorities (Hunt and Jung 2009; Jantzen 2005). Although guilt was not assessed, this finding also appears to be consistent with literature suggesting religious women experience guilt related to their sexual behaviors (Cowden and Bradshaw 2007), in part due to women’s perception that sex contradicts religious teachings (Leonard and Scott-Jones 2010). Further, women high in fundamentalism were less likely to value sex in their lives and aspirations. This finding appears consistent with literature that suggests religious teachings frequently value only procreative sex for women, as opposed to sex for pleasure (Jantzen 2005; Jung 2005).

Contrary to predictions, religious commitment and religious fundamentalism were positively related to the attractiveness domain of sexual self-esteem suggesting religious women positively evaluate their sexual attractiveness to a partner. One possibility is that religious women view themselves as creatures of God, a perfect being in whose image they are created, and accordingly, this may serve as a benefit for some religious women. For abstinent women with high religious fundamentalism, the relationship between religious fundamentalism and sexual attractiveness was no longer significant. This may suggest that fundamentally religious women, who may have received particularly rigid messages about sex including that sex is purely procreative, may find it challenging to view themselves as sexual beings prior to being sexual with a partner.

Women in the study with less permissive sexual attitudes did not have lower sexual self-esteem. In fact, women with permissive sexual attitudes were less likely to feel agency in their sexual life. One possibility is that, although they may perceive casual sex to be acceptable and pleasurable, from an early age women receive messages related to the dangerousness of sex, the potential for rape, and the stigma associated with women who are perceived as promiscuous. Therefore, it may be that desire for sex is negatively impacted by fear regarding safety and reputation that these messages create. Those with less permissive sexual attitudes may feel that they are in greater control of their sexual lives as a result of engaging in fewer and less risky sexual behaviors. This finding is consistent with the scholarship on the sexual double standard (Kreager et al. 2016; Lefkowitz et al. 2014; Rudman et al. 2012).

The fifth hypothesis that the relationship between religious commitment and sexual self-esteem was moderated by perception of God’s view of sex was not supported. However, results provided more support for Hypothesis 2 and confirmed that the direction of the relationship was such that religious commitment predicted perceived incongruence between women’s sexual behaviors and moral standards. The perception that God viewed sex negatively predicted the opposite, as women who believed God was restrictive regarding sex were more likely to feel their sexual behaviors were congruent with their moral standards. It may be that women who believe God approves of sex only in an attempt to procreate via penile-vaginal intercourse engage primarily in these sexual behaviors. Therefore, their behaviors are consistent with their religious beliefs regarding sex and they experience greater confidence in their moral judgment related to sex.

An exploratory analysis revealed that women who were raised Catholic had lower overall sexual-self esteem. The same was true for women who currently identified as Protestant and reported sexually permissive attitudes. The majority of participants identified as Christian (40.3 %), rather than a more specific denomination. It is possible that these participants retain a belief in Christian values without participation in organized forms of Christian faith. Additionally, the measure of religious commitment in this study did not require frequent church attendance in order to be considered religiously committed. Therefore, it may be that the majority of participants in the current study were not frequently exposed to the restrictive sexual messages regarding women’s sexuality that are sometimes communicated through religious authorities. Those who identified with a specific, formal denomination within Christianity may have attended services or encountered restrictive messages more frequently and, in turn, developed lower sexual self-esteem.

Limitations

One limitation of the current study is that partner status was not assessed. There may be differences in experiences of one’s sexuality when partnered versus unpartnered. The average age of participants was 20 years old, all were college students, and 43.4 % reported they were abstinent. This population may not have a great deal of sexual experience from which to draw and are also likely in a period of transition wherein they are distinguishing their personal values from those of their parents or caregivers. Specifically within Christian faith, sex is often celebrated in the context of marriage, while abstinence is still proscribed for those who are unmarried (Goddard 2015) and women in long-term committed relationships report greater satisfaction with sex as compared to women in relationships they expect to end (Waite and Joyner 2001). Therefore, married and partnered women may experience their sexual selves more positively than single women of faith. Of note, previous researchers have demonstrated that there is considerable variation in what college students consider abstinent behavior (Hans and Kimberly 2011) and the terms “sexually active” and “abstinent” were not defined for participants. Therefore, participants may have underreported sexual activity (DiClemente et al. 2011). Because we did not ask for more specificity of participants’ sexual activity and given the potential stigma of self-reporting sexual activity, our results should be interpreted cautiously.

The internal reliability of the PGS was relatively low (.76 and .68 for negative and positive items, respectively). Therefore, the PGS may not be a strong measure of perception of God’s view of sex in the current study. As a result, any findings related to the construct should be interpreted with caution.

Future Research

Future researchers should consider sampling a greater range of participants in age and sexual experience. It would also be beneficial to assess in a more detailed manner the level of sexual activity and in what types of sexual behaviors participants engage regularly. To assess further the unique experiences of women in this area, a comparison of sexual self-esteem between religious men and women could be performed. Given the current study’s results related to those who were raised Catholic or identify as Protestant, a sample consisting of individuals participating in more formal, organized religion may be useful. It may also be helpful to analyze the experiences of women related to their sexual self-esteem using qualitative methods in order to assess common themes in their perception of themselves sexually.

Conclusion

Women’s level of religious commitment impacts their sexual self-esteem in varied and complex ways. While some religious variables negatively impact the ways in which women perceive themselves sexually, such as in their evaluation of their moral judgment related to sex, others appear to strengthen their sexual self-evaluations, as in the case of sexual attractiveness. The current study suggests that religious women experience a marked discrepancy between the sexual behaviors in which they may engage and those they believe to be appropriate given their religious beliefs, such that they are less confident in their moral judgments related to sex. Conflicts regarding moral judgments and sexual activity could result in deleterious effects among religious women. Further research is necessary to continue to explore the complex relationship among gender, religion, sex, and moral judgment.

References

Ahrold, T. K., Farmer, M., Trapnell, P. D., & Meston, C. M. (2011). The relationship among sexual attitudes, sexual fantasy, and religiosity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 619–630. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9621-4.

Allen, K. R., & Brooks, J. E. (2012). At the intersection of sexuality, spirituality, and gender: Young adults’ perceptions of religious beliefs in the context of sexuality education. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 7, 285–308. doi:10.1080/15546128.2012.740859.

Altemeyer, B., & Hunsberger, B. (2004). A revised religious fundamentalism scale: The short and sweet of it. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 14(1), 47–54.

Arakawa, D. R., Flanders, C. E., Hatfield, E., & Heck, R. (2013). Positive psychology: What impact has it had on sex research? Sexuality and Culture, 17, 305–320. doi:10.1007/s12119-012-9152-3.

Barken, S. E. (2006). Religiosity and premarital sex in adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(3), 407–417.

Bonds-Raacke, J. M., & Raacke, J. (2011). Examining the relationship between degree of religiousness and attitudes toward elderly sexual activity in undergraduate college students. College Student Journal, 45(1), 134–142.

Breakwell, G. M., & Millward, L. J. (1997). Sexual self-concept and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Adolescence, 20, 29–41.

Brelsford, G. M., Luquis, R., & Murray-Swank, N. A. (2011). College students’ permissive sexual attitudes: Links to religiousness and spirituality. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 21, 127–136. doi:10.1080/10508619.2011.557005.

Browning, D. S., Green, M. C., & Witte, J, Jr. (Eds.). (2006). Sex, marriage, and family in world religions. New York: Columbia University Press.

Buzwell, S., & Rosenthal, D. (1996). Constructing a sexual self: Adolescents’ sexual self-perceptions and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6(4), 489–513.

Cochran, J. K., & Beeghley, L. (1991). The influence of religion on attitudes toward nonmarital sexuality: A preliminary assessment of reference group theory. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30(1), 45–62.

Cowden, C. R., & Bradshaw, S. D. (2007). Religiosity and sexual concerns. International Journal of Sexual Health, 19(1), 15–24. doi:10.1300/J514v19n01_03.

Davidson, J. K., Darling, C. A., & Norton, L. (1995). Religiosity and the sexuality of women: Sexual behavior and sexual satisfaction revisited. The Journal of Sex Research, 32(3), 235–243.

Davidson, J. K., Moore, N. B., & Ullstrup, K. M. (2004). Religiosity and sexual responsibility: Relationships of choice. American Journal of Health Behavior, 28(4), 335–346.

DiClemente, R. J., Sales, J. M., Danner, F., & Crosby, R. A. (2011). Association between sexually transmitted diseases and young adults’ self-reported abstinence. Pediatrics, 127, 208–214. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0892.

Edwards, L. M., Fehring, R. J., Jarrett, K. M., & Haglund, K. A. (2008). The influence of religiosity, gender, and language preference acculturation on sexual activity among Latino/a adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 30(4), 447–462. doi:10.1177/0739986308322912.

Espinosa-Hernandez, G., Bissell-Havran, J., & Nunn, A. (2015). The role of religiousness and gender in sexuality among Mexican adolescents. Journal of Sex Research, 52, 887–897. doi:10.1080/00224499.2014.990951.

Gil, V. E. (1990). Sexual fantasy experiences and guilt among conservative Christians: An exploratory study. The Journal of Sex Research, 27(4), 629–638.

Goddard, A. (2015). Theology and practice in evangelical churches. In A. Thatcher (Ed.), The oxford handbook of theology, sexuality, and gender (pp. 377–394). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Haffner, D. W. (2004). Sexuality and scripture. Contemporary Sexuality, 38(1), 7–13.

Hans, J. D., & Kimberly, C. (2011). Abstinence, sex, and virginity: Do they mean what we think they mean? American Journal of Sexuality Education, 6, 329–342. doi:10.1080/15546128.2011.624475.

Hendrick, C., Hendrick, S. S., & Reich, D. A. (2006). The brief sexual attitudes scale. The Journal of Sex Research, 43(1), 76–86.

Hensel, D. J., Fortenberry, J. D., O’Sullivan, L. F., & Orr, D. P. (2011). The developmental association of sexual self-concept with sexual behavior among adolescent women. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 675–684. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.005.

Hill, P. C., & Hood, R. W. (1999). Measures of religiosity. Birgmingham, AL: Religious Education Press.

Hunt, M. E., & Jung, P. B. (2009). “Good sex” and religion: A feminist overview. Journal of Sex Research, 46(2–3), 156–167. doi:10.1080/00224490902747685.

Impett, E. A., & Tolman, D. L. (2006). Late adolescent girls’ sexual experiences and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Adolescent Research, 21(6), 628–646. doi:10.1177/0743558406293964.

Jantzen, G. M. (2005). Good sex: Beyond private pleasure. In P. B. Jung, M. E. Hunt, & R. Balakrishnan (Eds.), Good sex: Feminist perspectives from the world’s religions (pp. 3–14). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Jung, P. B. (2005). Sanctifying women’s pleasure. In P. B. Jung, M. E. Hunt, & R. Balakrishnan (Eds.), Good sex: Feminist perspectives from the world’s religions (pp. 77–95). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Kimberly, C., Werner-Wilson, R., & Motes, Z. (2013). Brief report: Expanding the brief sexual attitudes scale. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 11(1), 88–93. doi:10.1007/s13178-013-0124-7.

Kreager, D. A., Staff, J., Gauthier, R., Lefkowitz, E. S., & Feinberg, M. E. (2016). The double standard at sexual debut: Gender, sexual behavior, and adolescent peer acceptance. Sex Roles: Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s11199-016-0618-x.

Lefkowitz, E. S., Gillen, M. M., Shearer, C. L., & Boone, T. L. (2004). Religiosity, sexual behaviors, and sexual attitudes during emerging adulthood. The Journal of Sex Research, 41(2), 150–159.

Lefkowitz, E. S., Shearer, C. L., Gillen, M. M., & Espinosa-Hernandez, G. (2014). How gendered attitudes relate to women’s and men’s sexual behaviors and beliefs. Sexuality and Culture, 18, 833–846. doi:10.1007/s12119-014-9225-6.

Leonard, K. C., & Scott-Jones, D. (2010). A belief-behavior gap? Exploring religiosity and sexual activity among high school seniors. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25(4), 578–600. doi:10.1177/0743558409357732.

Lindberg, L., & Maddow-Zimet, I. (2012). The consequences of sex education on teen and young adult sexual behaviors and outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51, 332–338. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.028.

Lou, J. H., Chen, S. H., Li, R. H., & Yu, H. Y. (2010). Relationships among sexual self-concept, sexual risk cognition and sexual communication in adolescents: A structural equation model. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 1696–1704. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03358.x.

Luquis, R. R., Brelsford, G. M., & Rojas-Guyler, L. (2012). Religiosity, spirituality, sexual attitudes, and sexual behaviors among college students. Journal of Religion and Health, 51, 601–614. doi:10.1007/s10943-011-9527-z.

Mayers, K. S., Heller, D. K., & Heller, J. A. (2003). Damaged sexual self-esteem: A kind of disability. Sexuality and Disability, 21(4), 269–282.

McFarland, M. J., Uecker, J. E., & Regnerus, M. D. (2011). The role of religion in shaping sexual frequency and satisfaction: Evidence from married and unmarried older adults. Journal of Sex Research, 48(2–3), 297–308. doi:10.1080/00224491003739993.

Miller, A. (2013). The non-religious patriarchy: Why losing religion has not meant losing white male dominance. Cross Currents, 63(2), 211–226. doi:10.1111/cros.12025.

Miller, B. C., Benson, B., & Galbraith, K. A. (2001). Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review, 21, 1–38. doi:10.1006/drev.2000.0513.

Njus, D. M., & Bane, C. M. H. (2009). Religious identification as a moderator of evolved sexual strategies of men and women. Journal of Sex Research, 46(6), 546–557. doi:10.1080/00224490902867855.

O’Sullivan, L. F., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., & McKeague, I. W. (2006). The development of the sexual self-concept inventory for early adolescent girls. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 139–149.

Oattes, M. K., & Offman, A. (2007). Global self-esteem and sexual self-esteem as predictors of sexual communication in intimate relationships. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 16(3–4), 89–100.

Oliver, M. B., & Hyde, J. S. (1993). Gender differences in sexuality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114(1), 29–51.

Owen, J., Fincham, F. D., & Moore, J. (2011). Short-term prospective study of hooking up among college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 331–341. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9697-x.

Pai, H. C., Lee, S., & Yen, W. J. (2012). The effect of sexual self-concept on sexual health behavioural intentions: A test of moderating mechanisms in early adolescent girls. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(1), 47–55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05710.x.

Penhollow, T., Young, M., & Denny, G. (2005). The impact of religiosity on the sexual behaviors college students. American Journal of Health Education, 36(2), 75–83.

Penhollow, T., Young, M., & Bailey, W. (2007). Relationship between religiosity and “hooking up” behavior. American Journal of Health Education, 38(6), 338–345.

Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2011). Gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: A review of meta-analytic results and large datasets. Journal of Sex Research, 48(2–3), 149–165. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.551851.

Pew Research Center. (2012). “Nones” on the rise: One-in-five adults have no religious affiliation. Retrieved from Pew Research Center website: http://www.pewforum.org/files/2012/10/NonesOnTheRise-full.pdf.

Rostosky, S. S., Dekhtyar, O., Cupp, P. K., & Anderman, E. M. (2008). Sexual self-concept and sexual self-efficacy in adolescents: A possible clue to promoting sexual health? Journal of Sex Research, 45(3), 277–286. doi:10.1080/00224490802204480.

Rowatt, W. C., & Schmitt, D. P. (2003). Associations between religious orientation and varieties of sexual experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(3), 455–465.

Rudman, L. A., Fetterolf, J. C., & Sanchez, D. T. (2012). What motivates the sexual double standard? More support for male versus female control theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 250–263. doi:10.1177/0146167212472375.

Runkel, G. (1998). Sexual morality of Christianity. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 24, 103–122. doi:10.1080/00926239808404924.

Toussaint, L. (2009). Associations of religiousness with 12-month prevalence of drug use and drug-related sex. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7, 311–323. doi:10.1007/s11469-008-9171-3.

Uecker, J. E. (2008). Religion, pledging, and the premarital sexual behavior of married young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 728–744.

Waite, L. J., & Joyner, K. (2001). Emotional satisfaction and physical pleasure in sexual unions: Time horizon, sexual behavior, and sexual exclusivity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 247–264. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00247.x.

Winter, L. (1988). The role of sexual self-concept in the use of contraceptives. Family Planning Perspectives, 20(3), 123–127. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2135700.

Worthington, E. L., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J., et al. (2003). The religious commitment inventory—10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 84–96. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.50.1.84.

Yip, A. K. T. (2005). Queering religious texts: An exploration of British non-heterosexual Christians’ and Muslims’ strategy of constructing sexuality-affirming hermeneutics. Sociology, 39(1), 47–65. doi:10.1177/0038038505049000.

Ysseldyk, R., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2010). Religiosity as identity: Toward an understanding of religion from a social identity perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 60–71. doi:10.1177/1088868309349693.

Zaleski, E. H., & Schiaffino, K. M. (2000). Religiosity and sexual risk-taking behavior during the transition to college. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 223–227. doi:10.1006/jado.2000.0309.

Zeanah, P. D., & Schwarz, J. C. (1996). Reliability and validity of the sexual self-esteem inventory for women. Assessment, 3(1), 1–15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Abbott, D.M., Harris, J.E. & Mollen, D. The Impact of Religious Commitment on Women’s Sexual Self-Esteem. Sexuality & Culture 20, 1063–1082 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-016-9374-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-016-9374-x