Abstract

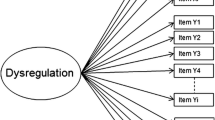

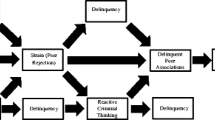

The purpose of this study was to determine whether a behavioral rating measure of low self-control and an attitudinal measure of low self-control can be viewed as measuring the same construct. It was hypothesized that the externalizing scale of the Behavior Problems Index (BPI-Ext), which served as a behavioral rating measure of low self-control in the current study, would display greater similarity to a 6-item self-report of antisocial, but not necessarily delinquent, behavior (SR-AB) measure than it would a 6-item attitudinal self-report measure of low self-control, labeled the reactive criminal thinking (SR-RCT) scale. This study was conducted on a sample of 6280 children (3144 boys, 3136 girls) from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth-Child (NLSY-C). A pair of confirmatory factor analyses revealed that the BPI-Ext and SR-RCT scales appeared to form two distinct constructs. In addition, the BPI-Ext correlated significantly better with the SR-AB than with the SR-RCT and the BPI-Ext and SR-AB achieved moderate negative correlations with measures of attention, concentration, achievement, and general aptitude, whereas the SR-RCT achieved small positive correlations. These results indicate that behavioral and attitudinal measures of low self-control are measuring different constructs, the former impulsive behavior and the latter reactive criminal thinking.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Agnew, R. (2011). Toward a unified criminology: Integrating assumptions about crime, people, and society. New York: New York University Press.

Allison, P. D. (2012). Handling missing data by maximum likelihood. In SAS global forum 2012, (Paper 312–2012). Cary: SAS Institute.

Arneklev, B. J., Cochran, J. K., & Gainey, R. R. (1998). Testing Gottfredson and Hirschi’s “low self-control” stability hypothesis: An exploratory study. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 23, 107–127.

Beaver, K. M., & Wright, J. P. (2007). The stability of low self-control, from kindergarten through first grade. Journal of Crime and Justice, 30, 63–86.

Bernard, T. J., & Snipes, J. B. (1996). Theoretical integration in criminology. Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, 20, 301–348.

Bindman, S. W., Pomerantz, E. M., & Roisman, G. I. (2015). Do children’s executive functions account for associations between early autonomy-supportive parenting and achievement through high school? Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 756–770.

Bollen, K., & Lennox, R. (1991). Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 305–314.

Bouffard, J., & Kunzi, T. (2012). Sexual arousal and self-control: Results from a preliminary experimental test of the stability of self-control. Crime and Delinquency, 58, 514–538.

Center for Human Resource Research (2009). NLSY79 user’s guide, CHRR NLS User Services. Columbus: The Ohio State University.

Conner, B. T., Stein, J. A., & Longshore, D. (2009). Examining self-control as a multidimensional predictor of crime and drug use in adolescents with criminal histories. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 36, 137–149.

DeLisi, M., & Vaughn, M. G. (2014). Foundation for a temperament-based theory of antisocial behavior and criminal justice system involvement. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42, 10–25.

Dishion, T. J., Spracklen, K. M., Andrews, D. W., & Patterson, G. R. (1996). Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy, 27, 373–390.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. (1981). PPVT: Peabody picture vocabulary test, revised. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

Dunn, L. M., & Markwardt, E. C. (1970). Manual for peabody individual achievement test. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

Ericson, R., & Carriere, K. (1994). The fragmentation of criminology. In D. Nelken (Ed.), The futures of criminology (pp. 89–109). London: Sage.

Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., & Jennings, W. G. (2013). Offending from childhood to late middle age: Recent results from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. New York: Springer.

Geis, G. (2000). On the absence of self-control as the basis for a general theory of crime: A critique. Theoretical Criminology, 4, 35–53.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Grasmick, H. G., Tittle, C. R., Bursik Jr., R. J., & Arneklev, B. K. (1993). Testing the core empirical implications of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 30, 5–29.

Hay, C., & Forrest, W. (2006). The development of self-control: Examining self-control theory’s stability thesis. Criminology, 44, 739–774.

Hindelang, M., Hirshi, T., & Weis, J. (1981). Measuring delinquency. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. (1993). Commentary: Testing the general theory of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 30, 47–54.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Jackson, D. B., & Beaver, K. M. (2013). The influence of neuropsychological deficits in early childhood on low self-control and misconduct through early adolescence. Journal of Criminal Justice, 41, 243–251.

Keogh, B. K. (2003). Temperament in the classroom: Understanding individual differences. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Krohn, M. D., Thornberry, T. P., Gibson, C. L., & Baldwin, J. M. (2010). The development and impact of self-report measures of crime and delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26, 509–525.

Lynam, D. R., & Miller, J. D. (2004). Personality pathways to impulsive behavior and their relations to deviance: Results from three samples. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 20, 319–341.

McKee, J. R. (2012). The moderation effects of family structure and low self-control. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 37, 356–377.

Muraven, M., Pogarsky, G., & Shmueli, D. (2006). Self-control depletion and the general theory of crime. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 22, 263–277.

Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. (1998–2007). Mplus user’s guide (5th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén.

Peterson, J. L., & Zill, N. (1986). Marital disruption, parent–child relationships, and behavioral problems in children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 48, 295–307.

Peyre, H., Leplége, A., & Coste, J. (2011). Missing data methods for dealing with missing items in quality of life questionnaires: A comparison by simulation of personal mean score, full information maximum likelihood, multiple imputation, and hot deck techniques applied to the SF-36 in the French 2003 decennial health survey. Quality of Life Research, 20, 287–300.

Pratt, T. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2000). The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime: A meta-analysis. Criminology, 38, 931–964.

Rennie, R., Beebe-Frankenberger, M., & Swanson, H. L. (2014). A longitudinal study of neuropsychological functioning and academic achievement in children with and without signs of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 36, 621–635.

Satorra, A. (2000). Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In R. D. H. Heijmans, D. S. G. Pollock, & A. Satorra (Eds.), Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis. A Festschrift for Heinz Neudecker (pp. 233–247). London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Steiger, J. H. (1980). Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 87, 245–251.

Turner, M. G., & Piquero, A. R. (2002). The stability of self-control. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30, 457–471.

Walters, G. D. (1995). The psychological inventory of criminal thinking styles: Part I. Reliability and preliminary validity. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 22, 307–325.

Walters, G. D. (2015). Early childhood temperament, maternal monitoring, reactive criminal thinking, and the origin(s) of low self-control. Journal of Criminal Justice, 43, 369–376.

Walters, G. D. (2016a). Are behavioral measures of self-control and the Grasmick self-control scale measuring the same construct? A meta-analysis. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 41, 151–167.

Walters, G. D. (2016b). Crime continuity and psychological inertia: Testing the cognitive mediation and additive postulates with male adjudicated delinquents. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 32, 237–252.

Walters, G. D. (2016c). Reactive criminal thinking as a consequence of low self-control and prior offending. Deviant Behavior. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/01639625.2016.1196951.

Walters, G. D. (2016d). Risk, need, and responsivity in a criminal lifestyle. In F. S. Taxman (Ed.), Handbook on risk and need assessment (pp. 193–219). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Walters, G. D., Hagman, B. T., & Cohn, A. M. (2011). Toward a hierarchical model of criminal thinking: Evidence from item response theory and confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Assessment, 23, 925–936.

Wechsler, D. (1974). Manual for the Wechsler intelligence scale for children—revised. New York: Psychological Corporation.

Whiteside, S. P., & Lynam, D. R. (2001). The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 669–689.

Wiebe, R. P. (2006). Using an expanded measure of self-control to predict delinquency. Psychology, Crime & Law, 12, 519–536.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walters, G.D. Measuring Low Self-Control and Reactive Criminal Thinking in the NLSY–Child Sample: One Construct or Two?. Am J Crim Just 42, 314–328 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-016-9365-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-016-9365-3