Abstract

Background

Whether compensation for professional services drives the use of those services is an important question that has not been answered in a robust manner. Specifically, there is a growing concern that spine care practitioners may preferentially choose more costly or invasive procedures in a fee-for-service system, irrespective of the underlying lumbar disorder being treated.

Questions/purposes

(1) Were proportions of interbody fusions higher in the fee-for-service setting as opposed to the salaried Department of Defense setting? (2) Were the odds of interbody fusion increased in a fee-for-service setting after controlling for indications for surgery?

Methods

Patients surgically treated for lumbar disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and spondylolisthesis (2006–2014) were identified. Patients were divided into two groups based on whether the surgery was performed in the fee-for-service setting (beneficiaries receive care at a civilian facility with expenses covered by TRICARE insurance) or at a Department of Defense facility (direct care). There were 28,344 patients in the entire study, 21,290 treated in fee-for-service and 7054 treated in Department of Defense facilities. Differences in the rates of fusion-based procedures, discectomy, and decompression between both healthcare settings were assessed using multinomial logistic regression to adjust for differences in case-mix and surgical indication.

Results

TRICARE beneficiaries treated for lumbar spinal disorders in the fee-for-service setting had higher odds of receiving interbody fusions (fee-for-service: 7267 of 21,290 [34%], direct care: 1539 of 7054 [22%], odds ratio [OR]: 1.25 [95% confidence interval 1.20–1.30], p < 0.001). Purchased care patients were more likely to receive interbody fusions for a diagnosis of disc herniation (adjusted OR 2.61 [2.36–2.89], p < 0.001) and for spinal stenosis (adjusted OR 1.39 [1.15–1.69], p < 0.001); however, there was no difference for patients with spondylolisthesis (adjusted OR 0.99 [0.84–1.16], p = 0.86).

Conclusions

The preferential use of interbody fusion procedures was higher in the fee-for-service setting irrespective of the underlying diagnosis. These results speak to the existence of provider inducement within the field of spine surgery. This reality portends poor performance for surgical practices and hospitals in Accountable Care Organizations and bundled payment programs in which provider inducement is allowed to persist.

Level of Evidence

Level III, economic and decision analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prior research has demonstrated a great degree of variation both in terms of indications for spine surgical intervention as well as the types of procedures performed for a wide range of similar spinal disorders [2, 5, 11, 15, 17, 20, 21]. Much of this variation involves the use of high-intensity, expensive surgical interventions such as instrumented interbody fusions [2, 5, 15, 17, 21]. At the same time, several authors have documented that the increase in the use of interbody fusion-based procedures was not only associated with increased risk of complications and cost, but also occurred to some extent in patients not typically indicated for these interventions such as those with lumbar spinal stenosis [2, 5, 17]. These issues are important, particularly as surgeons, practices, and hospitals look to respond to the number of cost containment initiatives introduced in the era of healthcare reform, including bundled payment programs, value-based purchasing, and Accountable Care Organizations [12].

One of the challenges to effectively studying procedural variation in spine surgery is that it is difficult to discern the source of disparities in surgical practice [7, 17, 20]. In many respects, provider inducement, wherein surgeons elect to use more expensive procedures because of a financial incentive, has been postulated as a source [1, 20]. The phenomenon of provider inducement has been described in a number of contexts, including renal transplantation [1] and primary care [7, 9, 13]. It has also been theorized to exist within the field of spine surgery [5, 17], especially in the context of interbody fusion because these procedures are estimated to pay as much as three times the amount for a decompression [5]. To the best of our knowledge, however, provider inducement within spine surgery has not been effectively studied in the past. This may be the result of the fact that it is often difficult to determine physician compensation through claims-based data capable of tracking large-scale variation in procedural performance. The TRICARE insurance plan of the Department of Defense (DoD) may serve as a more effective setting to investigate this phenomenon, however, given that the program functions within two different environments of care: purchased care in which beneficiaries receive services at civilian centers in the fee-for-service system and direct care in which services are provided at DoD facilities where providers are salaried employees or contractors of the DoD [3, 18, 22]. TRICARE is also a useful medium in which to conduct this research because the universal insurance coverage and benefits provided through the DoD eliminate an important confounder in surgical decision-making [3, 7, 18, 20, 22].

In this context, we sought to evaluate variation in procedural utilization for three common lumbar spinal disorders (disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and spondylolisthesis) within the fee-for-service and salaried healthcare settings. This is an ideal medium for the study of provider inducement because disc herniation and spinal stenosis are two conditions in which the standard intervention is considered a decompression procedure and not an interbody lumbar fusion, whereas the use of such interbody procedures is more generally accepted in the treatment of spondylolisthesis [5, 8, 10, 14, 17, 21]. In this context, were the use of interbody fusions to be increased among patients in the fee-for-service setting, this would be seen as a signal of provider inducement because, in this environment, reimbursement is directly tied to the type of procedure performed by the surgeon [1, 13, 17].

We therefore sought to use TRICARE data as a natural experiment to answer two questions: (1) Were proportions of interbody fusions higher in the fee-for-service setting as opposed to the salaried DoD setting? (2) Were the odds of interbody fusion increased in a fee-for-service setting after controlling for indications for surgery?

Patients and Methods

This was a retrospective study using information imparted to the Military Health System Data Repository (MDR) for beneficiaries receiving care under the auspices of the TRICARE insurance program between 2006 and 2014. TRICARE insurance is provided to all uniformed military employees of the DoD and their dependents as well as retirees and those separated as a result of a medical condition associated with greater than 30% disability [3, 18, 22]. TRICARE beneficiaries may receive care in the fee-for-service civilian setting (purchased care) or through a DoD medical facility (direct care) [3, 18, 22].

All major medical centers in the DoD provide spine surgical services through salaried employees (uniformed and civilian) or contractors who are orthopaedic spine surgeons or neurosurgeons [19]. TRICARE is not involved in the care of servicemembers in combat theaters [16] nor does the plan provide services through the Veterans Administration [18, 22]. TRICARE beneficiaries may receive care in the purchased care setting for a variety of reasons, including personal preference and location of their residence. There are currently no categories of patients that are systematically referred from the direct care to the purchased care setting. The MDR captures all information on inpatient and outpatient insurance claims handled through TRICARE irrespective of the environment of care or the location of service. TRICARE data have previously been utilized in other initiatives evaluating the delivery of surgical services in a number of different contexts [3, 18, 22]. Moreover, the broad demographic insured through TRICARE, which covers individuals of extremely varied sociodemographic, educational, professional, and vocational backgrounds, has been considered representative of the American population aged 18 to 64 years in prior studies [3, 16, 18, 22].

A query was performed using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes to identify all TRICARE beneficiaries aged 18 to 64 years surgically treated for a disc herniation (722.10, 724.4), lumbar spinal stenosis (721.42, 721.91, 724.02), and spondylolisthesis (738.4, 756.11, 756.12). Patients aged 65 years and older as well as those otherwise eligible for Medicare services were excluded from review. Revision procedures were not included. Demographic data were extracted for identified individuals including age at the time of surgery, race, biologic sex, census region, number of medical comorbidities as defined by the modified Charlson index [4], sponsor military rank, type of surgery performed, and whether services were delivered in the direct or purchased care setting. Race was defined as white or nonwhite with nonwhite including individuals characterized as black, Asian, Hispanic, and other race. Sponsor military rank was classified as officer, enlisted junior (lowest four ranks in any branch of service), senior enlisted (noncommissioned officers), and other (warrant officers and cadets). In line with prior research using TRICARE data, sponsor military rank was considered a proxy for socioeconomic status in this analysis with individuals in the enlisted junior category maintained to be representative of those in lower socioeconomic circumstances [6, 16, 18, 22]. The type of surgical intervention was determined using ICD-9 procedure codes and defined as discectomy, decompression, posterolateral fusion, and interbody fusion using a previously published algorithm [17].

Within each lumbar disorder (such as disc herniation, spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis), initial bivariate comparisons were made between the type of surgery (discectomy, decompression, posterolateral fusion, and interbody fusion) and the environment of care (purchased versus direct care) using the chi-square test. Adjustments were then made for case-mix (age, race, biologic sex, medical comorbidities, sponsor rank, and census region) using multinomial logistic regression. In regression testing, the direct care setting was used as the referent for the environment of care and interbody fusion was compared with the other types of surgical intervention. The results of regression tests were reported using an odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and p value. Statistically significant results were maintained to be those that demonstrated p values < 0.05 and 95% CIs exclusive of 1.0 after multinomial logistic regression analysis. All statistical testing was performed using SAS Version 9.3 (Cary, NC, USA). Our institutional review board determined that this investigation was exempt from full review.

A total of 28,344 patients met all inclusion criteria, 21,290 (75%) treated in the purchased care setting and 7054 (25%) in direct care. The average age of the entire study cohort was 43 years (SD 12) and 63% (n = 18,005) of the population were men (Appendix 1 [Supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR ®.]). Sixteen percent of the population had at least one medical comorbidity. The majority of patients (n = 17,046 of 28,344 [60%]) derived from the South. The fee-for-service setting treated patients who were older on average and a higher percentage of nonwhites, females, and those with a higher comorbidity count (Table 1). As a result of the size of our sample, there were differences in case-mix between the fee-for-service and salaried healthcare settings. Most patients (n = 18,900 of 28,344 [67%]) in both settings were treated for a diagnosis of disc herniation. Spondylolisthesis was the indication for surgery in 4705 of 28,344 instances (17%) with spinal stenosis diagnosed in 4739 of 28,344 (17%).

Results

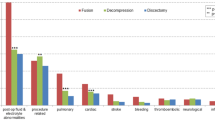

TRICARE beneficiaries treated for lumbar spinal disorders in the fee-for-service setting had higher odds of receiving interbody fusions (fee-for-service: 7267 of 21,290 [34%], direct care: 1539 of 7054 [22%], OR: 1.25 [1.20–1.30], p < 0.001). Fifty-five percent (3852 of 7054) of all procedures performed in the salaried DoD setting were discectomies as opposed to 39% (8222 of 21,290) of surgical interventions in the fee-for-service setting. Interbody fusions were performed in 22% (1539 of 7054) of all lumbar spine surgeries in the DoD setting as compared with 34% (7267 of 21,290) of procedures in the fee-for-service setting (Table 2).

Purchased care patients were more likely to receive interbody fusions for a diagnosis of disc herniation (adjusted OR 2.61 [2.36–2.89], p < 0.001) and for spinal stenosis (adjusted OR 1.39 [1.15–1.69], p < 0.001); however, there was no difference for patients with spondylolisthesis (adjusted OR 0.99 [0.84–1.16], p = 0.86). Beneficiaries with disc herniations in the fee-for-service setting were more likely to receive interbody fusions when compared with discectomies (adjusted OR: 2.66 [2.40–2.95], p < 0.001) and decompressions (adjusted OR: 4.17 [3.64–4.77], p < 0.001; Table 3). Individuals with lumbar spinal stenosis treated in the fee-for-service setting were also more likely to undergo interbody fusion as compared with discectomy (adjusted OR: 2.18, 95% CI, 1.58–3.01, p < 0.001) and decompression (adjusted OR: 1.67, 95% CI, 1.36–2.04, p < 0.001; Table 4). Among those with spondylolisthesis, no difference between the purchased care and direct care settings was encountered for treatment with decompression (adjusted OR: 1.72, 95% CI, 1.0–2.97, p = 0.05) or posterolateral fusion (adjusted OR: 0.99, 95% CI, 0.83–1.18, p = 0.91) as compared with interbody fusion (Table 5).

Discussion

Whether provider-induced demand, where compensation for professional services drives the use of those services, exists in the field of spine surgery is an important question that has yet to be sufficiently answered [1, 7, 9, 13]. Understanding the drivers of procedural variation in spine surgery is especially important in the health reform era, because the organizations best situated for success in this environment will be those that can effectively reduce unwanted surgical variation and diminish clinical waste [12, 17], including provider inducement if such a phenomenon truly exists. In this analysis we performed a natural experiment, evaluating variation in the use of interbody fusion procedures performed for three common lumbar disorders in the fee-for-service and salaried DoD settings of the TRICARE system. In the context of our study, whether a patient was treated in the direct or purchased care setting could be viewed as a random event, and if the use of interbody fusions was increased among patients in the fee-for-service setting, this would serve as a signal of provider inducement. The main findings of this study indeed point to the existence of such a phenomenon, because TRICARE beneficiaries treated in the fee-for-service setting had a higher likelihood of receiving interbody fusions regardless of the indication for surgery. Although these same patients were also more likely to receive interbody fusions for a diagnosis of disc herniation and for spinal stenosis, there was no difference in the utilization of interbody fusions for patients with spondylolisthesis between the direct and purchased care settings.

We recognize that there are a number of limitations associated with this work. Foremost, as a retrospective study that utilized administrative data, there is the potential for errors in coding and lack of clinical specificity to confound our results. We attempted to adjust for these issues to the fullest extent possible by accounting for differences in case-mix, including age and biologic sex, between beneficiaries treated in the disparate environments of care. Similarly, the lack of clinical specificity inherent in any claims-based analysis impairs our capacity to speak to the appropriateness of the interventions selected in either environment of care. It is possible that interbody fusion procedures may be overutilized in the fee-for-service setting or underutilized by salaried surgeons in DoD facilities, although our finding of no difference in the use of these procedures for the one indication (spondylolisthesis) in which such interventions are supported by studies [8, 10, 14] speaks against this fact. As a claims-based registry, we recognize that we do not have any information on radiographic findings, severity of disease, disability or pain scores, or procedural rationale. However, there is no evidence to support the contention that the rationale for surgical intervention or approaches to care differs between the fee-for-service and direct care settings [3, 18, 22]. Lastly, other than documenting differences in procedural selection between fee-for-service and salaried surgeons, we cannot truly elucidate their underlying motivations. Although differences in reimbursement remain the most likely explanation, other factors may influence surgical decision-making including the desire to remain technically proficient in the performance of specific procedures and intangible social and professional benefits that may accrue from being viewed as a highly skilled and productive surgeon irrespective of the means of compensation. We believe, however, that these social and professional motivations are as likely to exist among the orthopaedic spine and neurosurgical providers in the fee-for-service system as the salaried DoD environment and thus are not a logical explanation for the results encountered in this work.

TRICARE beneficiaries were more likely to receive lumbar interbody fusion procedures in the fee-for-service setting. Based on previous work [5, 17], this may be a direct result of provider inducement attributable to the increased reimbursement associated with interbody fusion procedures. The results of this analysis hold importance for surgeons, hospitals, third-party payers, and the federal government. Fusion-based procedures are known to be as much as three times as expensive as standalone decompression surgeries [5]. Moreover, they are also known to be associated with a higher risk of complications and readmission [5, 8, 17]. All of these factors may culminate in financial losses for centers treating large numbers of patients with spinal disorders in the postreform healthcare environment if provider inducement is allowed to persist. In addition, value-based purchasing models and narrowed insurer networks may indirectly target surgeons who engage in provider inducement as a result of their associated higher costs of care. This will adversely impact those surgical practices as well as the patients under their care.

Patients with disc herniations and spinal stenosis in the fee-for-service setting were also substantially more likely to receive an interbody fusion as opposed to the decompression-type procedure generally advocated in the literature [5, 14, 17, 20]. Like with most clinical variation in medicine, the phenomenon of provider inducement stems from a lack of consensus regarding optimal indications for procedure selection [17, 20]. Higher quality research and appropriate use guidelines from surgical societies and governing bodies may go a long way toward ameliorating clinical uncertainty on this topic. At the same time, surgeons and hospitals may elect to engage in external benchmarking regarding the use of interbody fusion procedures and the clinical rationale for such interventions. The inability to engage in these kinds of initiatives may engender situations in which surgical practices and hospital systems are positioned for failure in the risk-based reimbursement environment of American health care.

More expensive and complex interbody fusion procedures were performed at substantially greater rates in the fee-for-service setting in this study irrespective of the indication for surgery. In many instances, these procedures were performed on patients who did not have a generally accepted indication for a fusion-based intervention, including those with disc herniations and spinal stenosis. At the same time, no difference in the use of interbody fusion was appreciated between the fee-for-service and salaried healthcare settings for spondylolisthesis, a condition in which the need for these procedures is accepted. These results speak to the existence of provider inducement within the field of spine surgery. This reality portends poor performance for surgical practices and hospitals in Accountable Care Organizations and bundled payment programs in which provider inducement is allowed to persist.

References

Adler JT, Sethi RK, Yeh H, Markmann JF, Nguyen LL. Market competition influences renal transplantation risk and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2014;260:550–556.

Bae HW, Rajaee SS, Kanim LE. Nationwide trends in the surgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2013;38:916–926.

Bagchi AD, Stewart K, McLaughlin C, Higgins P, Croghan T. Treatment and outcomes for congestive heart failure by race/ethnicity in TRICARE. Med Care. 2011;49:489–495.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619.

Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI, Kreuter W, Goodman DC, Jarvik JG. Trends, major medical complications, and charges associated with surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303:1259–1265.

Enewold L, Zhou J, McGlynn KA, Anderson WF, Shriver CD, Potter JF, Zahm SH, Zhu K. Racial variation in breast cancer treatment among Department of Defense beneficiaries. Cancer. 2012;118:812–820.

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–287.

Ghogawala Z, Dziura J, Butler WE, Dai F, Terrin N, Magge SN, Coumans JV, Harrington JF, Amin-Hanjani S, Schwartz JS, Sonntag VK, Barker FG 2nd, Benzel EC. Laminectomy plus fusion versus laminectomy alone for lumbar spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1424–1434.

Helmchen LA, Lo Sasso AT. How sensitive is physician performance to alternative compensation schedules? Evidence from a large network of primary care clinics. Health Econ. 2010;19:1300–1317.

Kornblum MB, Fischgrund JS, Herkowitz HN, Abraham DA, Berkower DL, Ditkoff JS. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective long-term study comparing fusion and pseudarthrosis. Spine. 2004;29:726–733.

Lubelski D, Williams SK, O’Rourke C, Obuchowski NA, Wang JC, Steinmetz MP, Melillo AJ, Benzel EC, Modic MT, Quencer R, Mroz TE. Differences in the surgical treatment of lower back pain among spine surgeons in the United States. Spine. 2016;41:978–986.

Miller DC, Ye Z, Gust C, Birkmeyer N, Skinner J, Birkmeyer JD. Anticipating the effects of accountable care organizations for inpatient surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:549–554.

Nguyen NX, Derrick FW. Physician behavioral response to a Medicare price reduction. Health Serv Res. 1997;32:283–298.

Pearson AM, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Zhao W, Abdu WA, Weinstein JN. Who should undergo surgery for degenerative spondylolisthesis? Treatment effect predictors in SPORT. Spine. 2013;38:1799–1811.

Rajaee SS, Bae HW, Kanim LE, Delamarter RB. Spinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008. Spine. 2012;37:67–76.

Schoenfeld AJ, Goodman GP, Burks R, Black MA, Nelson JH, Belmont PJ Jr. The influence of musculoskeletal conditions, behavioral health diagnoses, and demographic factors on injury-related outcome in a high-demand population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e1061–1068.

Schoenfeld AJ, Harris MB, Liu H, Birkmeyer JD. Variations in Medicare payments for episodes of spine surgery. Spine J. 2014;14:2793–2798.

Schoenfeld AJ, Jiang W, Harris MB, Cooper Z, Koehlmoos T, Learn P, Weissman JS, Haider AH. Association between race and post-operative outcomes in a universally insured population versus patients in the state of California. Ann Surg. 2016 Aug 5. [Epub ahead of print].

Schoenfeld AJ, Lehman RA Jr, Hsu JR. Evaluation and management of combat-related spinal injuries: a review based on recent experiences. Spine J. 2012;12:817–823.

Schoenfeld AJ, Weiner BK, Smith HE. Regional variation and spine care: an historical perspective. Spine. 2011;36:1512–1517.

Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR, Bronner KK, Fisher ES. United States’ trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992-2003. Spine. 2006;31:2707–2714.

Zogg CK, Jiang W, Chaudhary MA, Scott JW, Shah AA, Lipsitz SR, Weissman JS, Cooper Z, Salim A, Nitzschke SL, Nguyen LL, Helmchen LA, Kimsey L, Olaiya ST, Learn PA, Haider AH. Racial disparities in emergency general surgery: do differences persist among universally insured military patients? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:764–777.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Henry M. Jackson Foundation of the Department of Defense (AHH).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Center for Surgery and Public Health, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Schoenfeld, A.J., Makanji, H., Jiang, W. et al. Is There Variation in Procedural Utilization for Lumbar Spine Disorders Between a Fee-for-Service and Salaried Healthcare System?. Clin Orthop Relat Res 475, 2838–2844 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-017-5229-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-017-5229-5