Abstract

The objective of this study was to evaluate the potential of double wall material combinations, using legume protein (soy protein isolate and pea protein isolate) in combination with wheat dextrin soluble fiber or trehalose, as alternative materials for microencapsulation of flaxseed oil by spray drying. The obtained preparations, with oil content of 35%, were fine and difficult flowing powders, regardless of their composition. The 1% addition of silica to the powders significantly reduced their cohesiveness and improved their flowability. The efficiency of microencapsulation, calculated based on oil fat content, ranged from 62 to 98% and was higher in the powders with trehalose and in the powders containing soy protein. Effective protection against oxidation of microencapsulated oil was achieved in the protein-trehalose matrix, especially in the case of the vacuum-packed powders with pea protein during storage at refrigeration temperature. Replacing trehalose with soluble fiber enabled formation of powders less susceptible to caking under conditions of increased humidity, but it resulted in decreased microencapsulation efficiency. The combination of pea protein/carbohydrate resulted in the formation of microcapsules with porous structure, especially in the system with soluble fiber. With time, the structure of the primary emulsions and those reconstituted from powders containing pea protein changed from liquid to greasy and paste-like.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flaxseed has drawn the attention of scientists, researchers, and industry due to its various health benefits. Although flaxseed oil, unlike fish oil, does not contain EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) or DHA (docosahexaenoic acid), it is still gaining popularity due to its high ω-3 fatty acid ALA (α-linolenic acid) content (Goyal et al. 2014). The role of ω-3 fatty acids in reducing the risks associated with cardiac and coronary disease, cancer, and other human health risk factors is well known (Gogus and Smith 2010). Consumer interest in foods fortified with ω-3 fatty acids has significantly increased. Modern techniques such as micro- and nanoencapsulation may, however, pave the way for new approaches to the processing, stabilization, and utilization of this oil (Bakry et al. 2016).

Spray drying is still the most commonly used technology for the encapsulation of oils (Gouin 2004, Gharsallaloui et al. 2007). The selection of the best coating materials is a crucial step in oil microencapsulation to result in powders with good quality, low water activity, easy handling and storage and also to protect oil rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids against oxidation (Bakry et al. 2016). There are some available reports on the optimization of flaxseed oil microencapsulation by spray drying using different wall materials (Omar et al. 2009, Tonon et al. 2012, Thirundas et al. 2014, Tontul and Topuz 2013, 2014, Barroso et al. 2014). Common wall materials for flaxseed oil microencapsulation were Arabic gum (GA), modified starches (octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA) starch), proteins (whey protein concentrate WPC and isolate WPI), and maltodextrin (MD). They were generally used in different double as well as triple wall material combinations, with the products being evaluated for encapsulation efficiency, product yield, oxidation stability, and surface characteristics. The same studies showed that whey protein is the most promising wall materials in combination with maltodextrin.

For instance, Tontul and Topuz (2013) optimized proportions of six triple wall material combinations for the highest microencapsulation efficiency and oxidation stability of flaxseed oil. They reported that the combination of OSA starch/GA/WPC in the ratio 4:0:1 provided the highest microencapsulation efficiency. However, the only successful combination in preventing flaxseed oil oxidation was MD/GA/WPC in the ratio 4:0:1. Moreover, Gallardo et al. (2013) reported that microcapsules made of 100% GA and ternary mixtures of GA, MD, and WPI were the most suitable wall material combination for flaxseed oil. Carneiro et al. (2013) evaluated the potential of MD combination with GA, (WPC) or two types of OSA starch at a 25:75 ratio. They reported that the lowest encapsulation efficiency was obtained for MD/WPC, while this combination was the wall material that best protected the active material against lipid oxidation.

Only a few studies have explored the use of vegetable protein to encapsulate flaxseed oil. The use of vegetable proteins as a wall material for the microencapsulation of various sensitive materials reflects the current “green” tendency in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries (Nesterenko et al. 2013). Bajaj et al. (2015) used three commercially available pea protein isolates (PPIs) alone as a wall material for the encapsulation of flaxseed oil and reported that microcapsules prepared with a 1:5 core-to-wall-material ratio had higher encapsulation efficiency than those produced with 1:3.3 and 1:2.5 ratios. The combination of proteins with carbohydrates as a carrier material favors better protection, oxidative stability, and drying properties (Augustin et al., 2006). It has been observed that flaxseed oil could be entrapped efficiently with MD combined with chickpea protein isolate or lentil protein isolate by spray drying and freeze drying, providing a protective effect against oxidation over a storage period of 25 days at room temperature and delivering more than 80% of the encapsulated oil to the gastrointestinal tract (Karaca et al. 2013).

The objective of this study was to evaluate the potential of double wall material combinations, using legume protein (soy protein isolate and pea protein isolate) in combination with a functional carbohydrate (wheat dextrin soluble fiber or trehalose), as alternative materials for the microencapsulation of flaxseed oil by spray drying. Microcapsules were characterized for morphology, size and density of particles, bulk density, content of interstitial air and flowability, free oil content and microencapsulation efficiency, wettability and dispersibility in water, as well as hygroscopicity and susceptibility to caking. In addition, the microencapsulated oil in powders kept under different storage conditions within 12 weeks was analyzed for its oxidative stability.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Flaxseed oil (fatty acid composition 7.5% SAFA (4.35% C16:0, 2.9% C18:0); 16.9% MUFA (16.6% C18:1 n-9); 76.8% PUFA (15.9% C18:2 (n-6 LA), 60% C18:3 (n-3 ALA)) was purchased from a company (Oleofarm, Poland) which regularly produces flaxseed oil by the cold pressing method. Pea protein isolate (NUTRALYS S85F) and wheat dextrin soluble fiber (NUTRIOSE FB06) were kindly donated by Roquette Poland Sp. z o.o. Soy protein isolate (SUPRO 670 IP) was obtained from Solae, USA. Trehalose (Hayashibara, Japan) was obtained from Hortimex, Poland. Silica Aerosil 2000 was acquired from Evonik, Germany. All chemicals used for analysis were of reagent grade.

Emulsion Preparation, Spray Drying, and Storage of Powders

Preparation of Emulsions

Primary oil-in-water emulsions, each in two batches, were prepared in the amount that allowed us to obtain about 500 g of powders ST, SF, PT, and PF with the raw material composition provided in Table 1. The wall materials (S, P, T, or F) were completely dissolved in distilled water at room temperature using a paddle agitator for 30 min and moved to cold storage (5 °C) for 24 h for components hydration. The flaxseed oil (54/100 g of dry weights of the wall materials) was added to the water phase and the mixture was emulsified by Ultra-Turrax (IKA T18 Basic, Wilmington, USA) at 13,000 rpm for 2 min. Emulsions were prepared by a final two-step homogenization at 60/20 MPa through two passes in a high-pressure homogenizer (Panda 2K; Niro Soavi, Italy).

Spray Drying

The spray drying of the oil-in-water emulsions was performed with a laboratory scale spray dryer (0.5–6 kg/h water evaporative capacity, Mobile Minor, Niro A/S, Denmark) equipped with a rotating disk for atomization. An inlet air temperature of 150 ± 3 °C and an outlet air temperature of 60 ± 2 °C were selected and disk rotation was at approximately 20,000 rpm. During drying, the outlet air temperature was controlled by the emulsion feed rate, which was 24–30 cm3/min.

The obtained powders contained 35% flaxseed oil, 55% carbohydrate (trehalose T or soluble fiber F), and 10% of legume protein (soy protein isolate S or pea protein isolate P), in accordance with the proportion of raw materials in dried emulsions, as presented in Table 1.

Storage

The oil powders were stored for 3 months in foil packages tightly closed using a vacuum welding/packaging machine PP-5.4 (Tepro, Poland). Bags made of PA/PE (polyamide/polyethylene) foil (95 μm) weighing 20 g served as unitary packages of samples. Bags made of four-layer foil (lacquer, paper, aluminum, and PE-LD low-density polyethylene), constituting a barrier to light, water vapor, and air, served as a collective package for four samples. Powder samples were stored in four variants of storage conditions: packaging in the non-modified atmosphere and vacuum packaging as well as room temperature of 25 °C and refrigeration temperature of 6 °C.

Analysis of Powders

Moisture Content, Water Activity

The moisture content of the powder was determined gravimetrically by drying it in a vacuum oven at 70 °C for 24 h (Domian et al. 2015b). Water activity a w (at a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C) was measured using a Rotronic DT1 instrument (Rotronic AG, Switzerland).

Particle Structure

The microstructure of the particles was investigated using a Hitachi TM3000 Tabletop scanning electron microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies Corp., Japan). Powder particles were attached to a sample stub with double-sided sticky tape and sputter coated with gold using a Cressington sputter coater 108 auto. Observations using SEM were made at an accelerating voltage of 5 or 15 kV at ×1000 magnifications. Representative micrographs were selected for presentation.

Particle Size Distribution

A laser light diffraction instrument, Cilas 1190 (Cilas, France), was used for determination of particle size of the powders and oil droplet size of emulsions reconstituted from powder. Particle size analysis of the powders was performed after dispersing in isopropanol. Distilled water was used as a dispersant for emulsions after the powders had been dissolved in water. Results are reported as the 10th, 50th (median), and 90th percentile of the volume distribution of particle size.

Density of Particles and Occluded Air Content

Apparent particle density (ρ) was determined by measuring the pressure change of helium in a calibrated volume with a gas pycnometer, Stereopycnometer (Quantachrome Instruments, USA). True particle density (ρ s ), defined as the theoretical density of powder solids, was calculated based on the densities and the amounts of the major components (water, carbohydrate, protein, and fat) (Soerensen et al. 1978). Occluded air (cm3/100 g), defined as the difference between the volume of a given mass of particles and the volume of the same mass of air-free solids, was calculated from the apparent (ρ) and true (ρ s ) densities, as follows: V oa = 100/ρ − 100/ρ s (Soerensen et al. 1978).

Bulk Density, Interstitial Air in Powder Bed, and Flowability

Loose bulk density (ρ L ) (bulk density of loosely poured material) and tapped bulk density (ρ t100, ρ t500, and ρ t1250) (bulk density of material packed with 100, 500, and 1250 standard taps) were determined using the jolting volumeter STAV 2003 (Engelsmann AG, Germany) with a measuring cylinder of 250 cm3. The ρ L and ρ t values were also determined with the addition of a preparation improving flowability, i.e., Aerosil 200 silica (Evonik Degussa, Germany), in the amount not exceeding 1% of powder.

Interstitial air (cm3/100 g), defined as the difference between the volume of a given mass of particles and the volume of the same mass of loose or 100× tapped powder, was calculated from the apparent particle density (ρ) and bulk densities (ρ L , ρ t100), respectively, as follows: V ia L = 100/ρ L − 100/ρ and V ia 100 = 100/ρ t100 − 100/ρ (Soerensen et al., 1978).

Flowability of powders was evaluated based on the Hausner ratio HR, which was calculated from the loose and tapped bulk densities, as follows: HR100 = ρ t100/ρ L , HR500 = ρ t500/ρ L and HR1250 = ρ t1250/ρ L (Domian et al. 2014, 2015b).

Free Oil and Microencapsulation Efficiency

Free oil content FO (g oil /100 g dry mass (d.m.) of powder) estimated for non-encapsulated fat in the microcapsules was determined using 24-h extraction with petroleum ether from a 3-g sample of powder (Kim et al. 2002) and gravimetric determination of the extracted fat.

Knowing the total content (TO) of fat in the powder resulting from the recipe and the content of free oil (FO), the microencapsulation effectiveness (ME) was computed using the following formula: ME (%) = ((TO − FO)/TO)100.

Reconstitution Property: Wettability and Dispersibility

The wettability (W 20°C and W 40°C) of a powder was determined as the time necessary to achieve complete wetting of a specified amount of powder (15.4 g), which corresponded to 10 g of non-fat dry matter, when it is dropped into 100 cm3 of water at a given temperature, i.e., 20 or 40 °C (Soerensen et al. 1978). The dispersibility (D 20°C and D 40°C) of a powder was determined as the time required to achieve complete dispersal, when it is manually stirred with a teaspoon until the powder is dispersed, leaving no lumps on the bottom of the glass.

Hygroscopicity and Susceptibility to Caking

The sorption capacity and the level of powder caking were determined based on the kinetics of water vapor adsorption at a temperature of 25 °C (Domian et al. 2014). Samples of powders with various initial water contents (1.5–2.3%) were re-dried and exposed to the effect of relative air humidity, i.e., RH 44, 65, and 75%, keeping them above saturated salt solutions for up to 48 h.

Oxidative Stability of Microencapsulated Oil

Oxidative stability of the microencapsulated flaxseed oil after 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks of powder storage was evaluated based on the peroxide value (LOO) compared to control samples of bulk oil that were stored without exposure to light in a closed vessel. LOO is expressed as milliequivalent of oxygen/kilogram of fat matter (meqO2/kg) and was obtained with the classic and simple iodometric method based on BS EN ISO 3960:2010, with chloroform and glacial acid as solvents.

Extraction of the lipid phase from the powder reconstituted in water was performed using an n-hexane/propan-2-ol mixture (3:1) according to the methodology of Kim et al. (2009) and Cesa et al. (2012). Six grams of powder was weighed and reconstituted with 50 cm3 of demineralized water at 40 °C, 70 cm3 of n-hexane/propan-2-ol was added to the powder, and the mixture was subjected to magnetic stirring for 15 min, centrifuged, and decanted. The upper phase was collected and the inner phase was added with 30 cm3 of n-hexane/propan-2-ol, twice. The collected organic phase was evaporated at room temperature under a reduced pressure and in the darkness. The obtained residue was weighed and titrated.

Statistical Analysis

Spray-drying experiments were conducted in duplicate. Each batch of powder was analyzed in at least two repetitions. The statistical analysis of results was conducted with Statistica 10.0 (StatSoft, Poland) using options of multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) considering the factors: type of protein component (levels: pea protein isolates and soy protein isolates) and type of carbohydrate component (levels: soluble fiber and trehalose), and additionally the packaging method (levels: non-modified atmosphere, vacuum packaging), storage temperature (levels: room, refrigerating), and storage period (0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks). Differences between mean values were evaluated with the Tukey test at a significance level of α = 0.05, with homogeneous groups of mean values denoted by letter classification.

Results and Discussion

Structure, Size, and Density of Particles of Microencapsulated Oil Powders

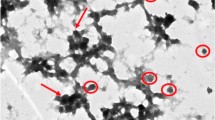

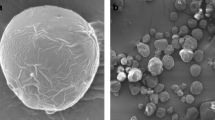

Figure 1 presents micrographs of microencapsulated oil powders. The obtained particles were characterized by various shapes and sizes. In the case of ST and PT powders, with trehalose contained in the matrix, the particles had a regular, spherical shape. The SF and PF microcapsules containing soluble fiber were characterized by an irregular shape with multiple indents and craters. The surface of ST and SF microcapsules containing soy protein isolate was smooth, whereas that of PT and PF particles containing pea protein isolate had numerous pores and cracks of various sizes.

Micrographs (magnification ×1000) of microencapsulated oil powder (raw powder composition in Table 1): ST powder with soy protein and trehalose, SF powder with soy protein and soluble fiber, PT powder with pea protein and trehalose, PF powder with pea protein and soluble fiber

Considering the regular shape of particles with trehalose, it may be hypothesized that the drying of emulsions with low-molecular-weight sugar results in the hardening of the surface and formation of spherical particles. They are able to inflate or expand and solidify with fewer indents on the surface. Similar spherical microcapsules of oil were produced in the following systems: OSA starch and trehalose or glucose syrup (Drusch et al. 2006; Serfert et al. 2009, Domian et al., 2015a, b), sodium caseinate or whey protein isolate with trehalose (Domian et al. 2014), combinations of gelatin, xanthan, sucrose and trehalose (Huang et al. 2014), and combinations of gum Arabic, maltodextrin DE 10, and whey protein isolate (Gallardo et al. 2013). The structure of microcapsules presenting a rounded external surface with characteristic concavities may point to high viscoelasticity of the matrix, which was collapsing during drying. Microcapsules with characteristic dents were obtained upon microencapsulation of flaxseed oil with gum Arabic alone (Tonon et al. 2011), combinations of gum Arabic, maltodextrin DE18, lecithin and xanthan gum (Omar et al. 2009), gum Arabic, whey protein concentrate, or modified starch alone (Tonon et al. 2012), maltodextrin mixed with gum Arabic, whey protein concentrate or modified OSA starch (Carneiro et al. 2013, Gallardo et al. 2013), and commercially available pea protein isolates alone (Bajaj et al. 2015).

The above shows that the hydrocolloid (protein, gum, or starch) content, as of other solutes and lipophilic compound, considerably affects the surface structure. The total feed concentration as well as each component may have influenced the rheology of the drying matrix and, hence, the final particle structure. Smooth surfaces are found in powders made from protein isolates that are mostly soluble and can form a thin, continuous elastic film as the water evaporates. After a flexible skin is completely formed, whose composition represents the faster depositing solute (protein), a crust then forms underneath the skin (Xu et al. 2012). However, hollow spray-dried particles with large internal voids can be observed both in rough and dent-free powders.

The mean diameter of particles (median D50) ranged from 18 to 40 μm (Table 2). The other equivalent diameters D10 and D90 ranged from 10 to 18 μm and from 39 to 81 μm, respectively (Table 2). The ANOVA analysis demonstrated that the particle size of powders containing soy protein was significantly larger, especially in those with trehalose. A similar size of particles in the range of 10 or so micrometers was determined in oil microcapsules in many studies when laboratory spray dryers were used (Serfert et al. 2009; Carneiro et al. 2013).

Tendencies for increasing powder particle size upon a change of protein pea isolate to soy protein isolate were reflected in the content of the occluded air. The apparent density (ρ) of particles ranged from 1.15 to 1.25 g/cm3 (Table 2). Occluded air content ranged from 0.4 to 8.6 cm3/100 g powder (Table 2), and its highest values were determined in the powders containing soy protein and trehalose. The powders containing pea protein did not show any significant differences between the apparent density of particles and density of the material constituting the particle (including water). It may indicate that either the number of pores entrapped inside particles was insignificant or the powder matrix was porous enough to allow helium with the pressure of 17 psi (a measuring medium of a gas pycnometer) to penetrate inside the particles.

Loose bulk density of powders and bulk density of 100× tapped powders reached ρ L 0.385–0.422 g/cm3 and ρ t100 0.516–0.584 g/cm3, respectively (Table 3). Irrespective of material composition, the powders were characterized by a high content of interstitial air which attained the values of V ia L = 156–171 cm3/100 g for the loosely poured bed and V ia 100 = 91–110 cm3/100 g for the 100× tapped bed (measurement conditions adopted as standard packing of milk powders, Soerensen et al. 1978) (Table 3). Naturally, such a high content of interstitial air may affect the oxidative stability of oil powders. The ANOVA analysis demonstrated that the powders with pea protein addition were characterized by a significantly higher bulk density and a significantly lower content of interstitial air in the bed compared to the powders containing soy protein. The carbohydrate component applied had no significant effect on the obtained values.

A similar range of bulk density of microencapsulated flaxseed oil was obtained by Tonon et al. (2011) and Aghbashlo et al. (2013). They demonstrated that the loose bulk density of powders could be affected by the inlet temperature of spray drying and by the concentration of emulsion.

According to de Jong et al. (1999), powders with HR 1–1.25, 1.25–1.4, and >1.4 are, respectively, free flowing, easily flowing, and difficult flowing, whereas according to Fitzpatrick (2013), powders with HR 1.00–1.11, 1.12–1.18, 1.19–1.25, 1.26–1.34, 1.35–1.45, 1.46–1.59, and >1.60 have, respectively, excellent, good, fair, passable, poor, very poor, and extremely poor flowability. Assuming the classification according to the Hausner index, it may be concluded that the flowability of the analyzed powders was poor, regardless of their composition, and was deteriorating along with the degree of bed packing (Table 3). Already in the state of medium packing, the spray-dried powders may be classified as poorly flowing. In the tapped state, however, the same powders may be classified as very difficult flowing as values of their HR500 and HR1250 exceeded the boundary value of 1.6. Because modification of the composition of powders had no significant effect on the HR, it may be concluded that the factor which determined their high cohesiveness and poor flowability was the small particle size (less than 100 μm). The 1% addition of Aerosil silica to powders considerably decreased their cohesiveness (Fig. 2) and improved their flowability (Table 3). The powders with silica were characterized by very good or good flowability, because HR100, HR500, and HR1250 values ranged from 1.08 to 1.30.

The effect of reducing flowability of material along with an increasing degree of bed packing in fine powders obtained in this study was consistent with findings of other authors (Domian and Cenkier 2013, Domian et al. 2014, Samborska et al. 2015, Szulc and Lenart 2016). Drusch et al. (2006) applied various flowability-improving preparations in powders of fish oil and determined their optimal addition at the level of 1%. They achieved the best results upon the use of a colloidal Aerosil silica.

Free Oil Content, Microencapsulation Efficiency, and Oxidative Stability of Microencapsulated Oil

The content of total free oil (FO) ranged from 0.5 to 13.4 g/100 g powder (Table 4). The efficiency of microencapsulation (ME) calculated based on FO ranged from 98 to 94% in the microcapsules with the protein-trehalose matrix and from 81 to 62% in the microcapsules with the protein-soluble fiber matrix (Table 4). The ANOVA analyses showed a lower content of free oil and higher ME in the powders with trehalose and in the powders containing soy protein.

Similar observations were made by Huang et al. (2014), who demonstrated that trehalose addition to the walls of microcapsules caused an increase in ME compared to analogous samples with only saccharose as a carbohydrate component. Carneiro et al. (2013) obtained ME in the range of 62.3 to 95.7% when flaxseed oil was encapsulated using a combination of maltodextrin with modified starches, whey protein concentrate, or gum Arabic. Gharsallaoui et al. (2007) reported that ME of microcapsules was influenced by the ratio between the core and wall material. Bajaj et al. (2015) obtained ME in the range of 90.46 to 71.9% for three commercially available pea protein isolates when the core-to-wall material ratio was at 1:5, and ME decreased to 67.9–44.6% when the core-to-wall-material ratio increased to 1:2.5. Goula and Adamopoulos (2012), as well as Huynh et al. (2008), demonstrated that the enhanced ME was due to emulsion droplet size, i.e., the lower the droplet size was, the higher was the ME. The ME values in this study cannot be compared with the results from other studies since none of them has investigated the use of a mixture of trehalose or soluble fiber and a legume protein at 35% of flaxseed oil active core material.

Radicals are formed in the early stage of lipid oxidation, and can in dry systems be stabilized by low molecular mobility. The level of free radicals is a good indicator of early stages of oxidation in dried products such as milk powders, and consequently has been suggested to be applied as a method for predicting the oxidative stability of lipids in such products. In the present study, stability of microencapsulated oils after powder storage was evaluated based on the peroxide value (LOO). According to the physiochemical requirements adopted by the producer, the LOO of flaxseed oil stored for up to 3 months under refrigerating conditions (4–10 °C) in a closed bottle, away from sources of light, should not exceed 5 meqO2/kg in this period. The LOO0 of bulk oil used for microencapsulation reached 0.87 meqO2/kg, and during 12-week storage at both refrigerating and room temperature increased to 2.8 meqO2/kg, regardless of the degree of filling of the vessel with oil (Table 5). Hence, the quality of bulk oil was preserved even during storage at room temperature.

The LOO of microencapsulated oil measured immediately after drying ranged from 1.80 to 7.90 meqO2/kg. The differences in LOO were linked with powder composition, but they were also observed among batches of powders with the same composition. So large differences in LOO after drying might be associated with high instability of the flaxseed oil and with other variables that were not controlled, despite maintaining identical conditions of homogenization during the production of emulsions and of drying conditions. An increase in the LOO after the microencapsulation was also observed by other scientists, who explained it as being due to a high temperature of spray drying. For instance, Kolanowski et al. (2006) reported an increase in the peroxide value of fish oil from 1.05 to 2.10 or 4.06 meqO2/kg after spray drying depending on oil loading. Ahn et al. (2008) obtained significantly higher LOO (15.2 meqO2/kg) soon after drying of sunflower oil in a matrix of milk protein isolate and soy lecithin, with LOO of 8.7 meqO2/kg obtained in optimal conditions. These authors focused attention on optimizing ME because, as they had demonstrated, oil is subject to significantly more rapid oxidation on the surface of microcapsules compared to the oil entrapped in the capsules. Tonon et al. (2011) observed that a lower content of solid substances and a higher load of flaxseed oil in the emulsion resulted in a higher content of peroxides immediately after drying, which was linked with a high free oil content and inlet air temperature above 170 °C. Similar observations regarding the optimal inlet temperature were made by Aghbashlo et al. (2013).

In this study, in the case of each stored powder, the LOO of microencapsulated flaxseed oil differed from that of bulk oil. Changes in the LOO of microencapsulated oil depended on powder composition, packaging method, and storage temperature, which was noticeable in graphs of expected mean values of the LOO shown in Fig. 3. After 12 weeks of storage, the LOO of microencapsulated oil ranged from ca. 4 to 27 meqO2/kg, but still LOO values not exceeding 5 meqO2/kg were determined only in PT powders stored under refrigerating conditions in vacuum packages.

Graph of expected mean peroxide values (LOO) of oil microencapsulated in powders during storage; effects of factors: protein component (soy protein, pea protein), carbohydrate component (trehalose T, soluble fiber F), storage time (0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks), and packaging method (non-modified atmosphere—air, vacuum packaging—vac) during storage at a room temperature of 24 °C, b refrigeration temperature 6 °C. Vertical bars denote 0.95 confidence interval

The four-way ANOVA of the powders stored at room temperature demonstrated that an increase in the mean LOO value occurred along with (in descending order of the extent of the effect of the mentioned factor) increase of storage time; change of the carbohydrate component—trehalose to soluble fiber; change of the protein component—pea protein isolate (PPI) to soy protein isolate (SPI); and change of the vacuum package to a package with air (Fig. 4a). The evaluation of effects of the main factors in the ANOVA conducted for powders stored at refrigeration temperature demonstrated the expected increase of LOO most of all as a result of the PPI change to SPI as well as the trehalose change to soluble fiber, followed by increase of storage time. In contrast, the packaging method had no significant effect on the LOO value (Fig. 4b). Results of the ANOVA conducted for factorial systems with repeated measurements confirmed that storage temperature and types of protein and carbohydrate components used in the matrix were the factors which had the greatest effect on the inhibition of flaxseed oil oxidation. The most effective protection against oxidation of microencapsulated oil was achieved in the protein-trehalose matrix, especially in the system with PPI, during storage of powders in a barrier vacuum package at refrigeration temperature.

Effect of main factors: protein component (soy protein, pea protein), carbohydrate component (trehalose T, fiber F), packaging method (non-modified atmosphere—air, vacuum packaging—vac), and storage time (0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks) on mean peroxide values (LOO) during storage at a room temperature of 24 °C, b refrigeration temperature 6 °C. Vertical bars denote 0.95 confidence interval

The above results confirm that penetration of oxygen into and through a glassy food matrix is a slow process, which may become rate limiting, in effect protecting flavor and nutrients against oxidation (Hedegaard and Skibsted 2013). Goyal et al. (2015) produced microcapsules with a high content of flaxseed oil (over 35% w/w, on a dry basis) using milk protein/lactose (1:1). They concluded that the developed flaxseed oil powder was stable throughout the storage of 6 months, and its peroxide value remained below the maximum permissible limit (≤5 meq per kg oil) stipulated in Codex Alimentarius Commission. Small molecules such as oxygen have been shown to penetrate through glassy food matrices with a temperature-dependent rate, which at low temperature becomes limiting for the rate of oxidation of encapsulated oil, resulting in a significant temperature dependence due to the requirement of thermal activation for penetration (Andersen et al. 2000; Orlien et al. 2000). Radicals from oxidizing lipids may transfer to proteins and amino acids, leading to protein degradation, as radicals also may transfer from proteins to lipids under other conditions and initiate lipid oxidation (Østdal et al. 2002). Hence, the radical interactions in microcapsule systems are important in determining their stability and consequently for prediction of the shelf-life of this type of dry preparations. In this study, we focused only on the determination of the peroxide value LOO, which indicates the content of peroxides characterized by the primary degree of lipid oxidation. Of course, the evaluation of oxidative changes in fat should take into account many other determinations in order to provide a full picture of changes occurring in fat both at the stage of drying and later storage.

Reconstitution Property and Stability of Emulsions Reconstituted from Powders

Rehydration of food powder generally undergoes the following phases corresponding to relevant reconstitution properties: wetting of particles, sinking, dispersing, and particles dissolving into solution (Fang et al. 2007). Powders are characterized by instant properties if the total time of their reconstitution ranges from a few to a few dozen seconds (Hogekamp and Schubert 2003; Westergaard 2004).

In the present study, the time of powders wetting (without stirring) and dispersing (gentile stirring) in water at temperatures of 20 and 40 °C was significantly affected by their composition (Table 4). Higher wettability and dispersibility were found in the preparations containing trehalose, especially in combination with soy protein isolate. Upon contact with water, the ST and PT particles reached complete wetting, and started to disperse and dissolve within 60 s, while the SF and PF particles swelled within >300 s in water. Better reconstitutability of the powders with trehalose confirmed that the systems with amorphous low-molecular-weight sugar are characterized by increased solubility and dissolution rate (Palzer 2010), which may lead to greater availability of the microencapsulated active substance and, appropriately, to its improved bioavailability.

The analysis of particle size distribution in reconstituted emulsions revealed bimodal distributions (Fig. 5). Populations of smaller particles probably were forming oil globules, whereas populations of larger particles could form aggregates of destabilized or non-dissolved particles suspended in water. Values of d50 of particle size in emulsions reconstituted a few hours after their preparation ranged from 6 to 20 μm (Table 4).

Instability of emulsions often results from two diverse physical processes: increased particle size upon coalescence or flocculation, and migration of particles leading to creaming (Domian et al., 2015a, b). In the present study, even after a few days of storage, no effects were observed resulting from destabilization of emulsions reconstituted from ST and SF powders. In turn, in PF and PT emulsions, flocculation could be observed as early as on the second day, which consisted in the concentration of the resultant aggregates accompanied by the formation of clear zones of the serum being formed, as well as a change in the consistency from liquid to greasy and paste-like. However, a clear separation of the oil phase was not observed in any of the systems. These observations are consistent with other studies which showed that pea protein isolate formed a paste instead of a rigid gel (Adebiyi and Aluko 2011). O’Kane et al. (2004) stated that pea protein forms more unstructured gels than soy protein and thus their gelling properties are not as good as those of soy.

Hygroscopicity and Susceptibility to Caking

It has been proven that storing food powders at a low initial water activity (a w ) of ~0.2 is helpful in avoiding stickiness and caking during storage. Also, it is clear that if there is a slight increase in moisture content, the a w of powders will be increased and these products are likely to be stickier (Bhandari and Hartel 2005). Depending on storage conditions, deterioration of spray-dried powders is initiated by changes in the physical state of the powder such as collapse of glassy states followed by crystallization. Water adsorption is the major factor responsible for crystallization of glassy sugars, as well any significant depression in Tg of any food material (Sillick and Gregson 2010). Crystallization will usually not take place below Tg within the time frame relevant for handling and storage of food powders, and storage for shorter time periods above Tg is normally also acceptable (Thomsen et al. 2005).

Figure 6 presents water adsorption kinetic curves depicting changes of water content in the powders. Crystallization of amorphous trehalose in PT and ST powders containing this saccharide, clearly indicated by a significant decrease in water content, occurred at relative humidity (RH) of 65% after 7–11 h and at RH of 75% after 5–6 h of storage, depending on the sample type. The sufficient level of adsorbed water that determined the phase transition of trehalose and release of adsorbed water by the crystalline forms being formed ranged from 0.21 to 0.23 g/g d.m. in the case of ST powders and from 0.18 to 0.2 g/g d.m. in the case of PT powders. In the case of powders containing soluble fiber (PF and SF), water adsorption proceeded without any noticeable phase transitions and was characterized by a successive increase of water content in time. The final water content in the powders, after 48 h of samples’ equilibration stabilized at the level of 1.1–1.2 g/g d.m., 1.5–1.7 g/g d.m., and 1.6–2.3 g/g d.m. at the RH of 44, 65, and 75%, respectively.

The effect of crystallization of amorphous trehalose at RH higher than 40% obtained in this study was consistent with the findings of other authors (Drusch et al. 2006, Schebor et al. 2010, and Domian et al. 2014, 2015b). For instance, Cerdeira et al. (2005) and Vega et al. (2007) observed trehalose crystallization in oil microcapsules at RH >50%.

After adsorption at RH 44%, no significant changes were observed in the appearance of any of the powders—there was no additional caking of the sample, and lumps present in the vessel disintegrated after shaking. At RH 65 and 75%, the powders with trehalose were subject to permanent caking to the form of aggregates and partially dissolved particles, and the color of powders changed noticeably towards yellow. In the case of the powders containing soluble fiber, significant changes in their appearance were observed only at RH 75%. Particles of these powders formed aggregates that were, however, not stable, and the powder was separating during shaking.

Conclusions

The results obtained in the study indicate that legume protein, soy protein isolate, and pea protein isolate, in combination with wheat dextrin soluble fiber or trehalose, generally meet the requirements expected from carrier materials during microencapsulation of lipid substances. The obtained preparations, with oil content of 35%, were fine and difficult flowing powders, regardless of their composition. The 1% addition of silica to the powders significantly reduced their cohesiveness and improved their flowability. Effective protection against oxidation of microencapsulated flaxseed oil was achieved only in the pea protein-trehalose matrix in the case of the vacuum-packed powders during storage at refrigeration temperature. The lower film-forming properties of pea proteins compared to soy proteins, despite comparable emulsifying properties, resulted in the formation of microcapsules with a porous structure and a significantly higher content of free oil, especially in the system with soluble fiber. The efficiency of microencapsulation, calculated based on oil fat content, ranged from 62 to 98% and was higher in the powders with trehalose and in the powders containing soy protein. Replacing trehalose with soluble fiber enabled formation of powders less susceptible to caking under conditions of increased humidity, but it resulted in decreased microencapsulation efficiency. It was demonstrated that the glassy matrix of trehalose coupled with legume protein offers the possibility of developing a powdered preparation with a low content of free oil and good reconstitutability in water. Even after a few days of storage, no effects were observed resulting from destabilization of emulsions reconstituted from powders with soy protein. In turn, with time, the structure of the emulsions reconstituted from powders containing pea protein changed from liquid to greasy and paste-like.

References

Adebiyi, A. P., & Aluko, R. E. (2011). Functional properties of protein fractions obtained from commercial yellow field pea (Pisum sativum L.) seed protein isolate. Food Chemistry, 128, 902–908.

Aghbashlo, M., Mobli, H., Madadlou, A., & Rafiee, S. (2013). Influence of wall material and inlet drying air temperature on the microencapsulation of fish oil by spray drying. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 6(6), 1561–1569.

Ahn, J. H., Kim, Y. P., Lee, Y. M., Seo, E. M., Lee, K. W., & Kim, H. S. (2008). Optimization of microencapsulation of seed oil by response surface methodology. Food Chemistry, 107(1), 98–105.

Andersen, A. B., Risbo, J., Andersen, M. L., & Skibsted, L. H. (2000). Oxygen permeation through an oil-encapsulating glassy food matrix studied by ESR line broadening using a nitroxyl spin probe. Food Chemistry, 70(4), 499–508.

Augustin, M. A., Sanguansri, L., & Bode, O. (2006). Maillard reaction products as encapsulants for fish oil powders. Journal of Food Science, 71(2), E25–E32.

Bajaj, P. R., Tang, J., & Sablani, S. S. (2015). Pea protein isolates: novel wall materials for microencapsulating flaxseed oil. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 8(12), 2418–2428.

Bakry, A. M., Abbas, S., Ali, B., Majeed, H., Abouelwafa, M. Y., Mousa, A., & Liang, L. (2016). Microencapsulation of oils: a comprehensive review of benefits, techniques, and applications. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 15(1), 143–182.

Barroso, A. K. M., Pierucci, A. P. T. R., Freitas, S. P., Torres, A. G., & Rocha-Leão, M. H. M. D. (2014). Oxidative stability and sensory evaluation of microencapsulated flaxseed oil. Journal of Microencapsulation, 31(2), 193–201.

Bhandari, B. R., & Hartel, R. W. (2005). Phase transitions during food powder production and powder stability. In C. Onwulata (Ed.), Encapsulated and powdered foods (pp. 261–292). New York: Taylor & Francis.

BS EN ISO 3960:2010 Animal and vegetable fats and oils. Determination of peroxide value. Iodometric (visual) endpoint determination

Carneiro, H. C., Tonon, R. V., Grosso, C. R., & Hubinger, M. D. (2013). Encapsulation efficiency and oxidative stability of flaxseed oil microencapsulated by spray drying using different combinations of wall materials. Journal of Food Engineering, 115(4), 443–451.

Cerdeira, M., Martini, S., & Herrera, M. L. (2005). Microencapsulating properties of trehalose and of its blends with sucrose and lactose. Journal of Food Science, 70(6), e401–e408.

Cesa, S., Casadei, M. A., Cerreto, F., & Paolicelli, P. (2012). Influence of fat extraction methods on the peroxide value in infant formulas. Food Research International, 48(2), 584–591.

Domian, E., & Cenkier, J. (2013). Flowability and homogeneity of food powders with plated oil ingredient. Journal of Food Process Engineering, 36(5), 626–633.

Domian, E., Sułek, A., Cenkier, J., & Kerschke, A. (2014). Influence of agglomeration on physical characteristics and oxidative stability of spray-dried oil powder with milk protein and trehalose wall material. Journal of Food Engineering, 125, 34–43.

Domian, E., Brynda-Kopytowska, A., & Oleksza, K. (2015a). Rheological properties and physical stability of o/w emulsions stabilized by OSA starch with trehalose. Food Hydrocolloids, 44, 49–58.

Domian, E., Brynda-Kopytowska, A., Cenkier, J., & Świrydow, E. (2015b). Selected properties of microencapsulated oil powders with commercial preparations of maize OSA starch and trehalose. Journal of Food Engineering, 152, 72–84.

Drusch, S., Serfert, Y., Van Den Heuvel, A., & Schwarz, K. (2006). Physicochemical characterization and oxidative stability of fish oil encapsulated in an amorphous matrix containing trehalose. Food Research International, 39(7), 807–815.

Fang, Y., Selomulya, C., & Chen, X. D. (2007). On measurement of food powder reconstitution properties. Drying Technology, 26(1), 3–14.

Fitzpatrick J. (2013). Powder properties in food production systems. In: Bhandari, B., Bansal, N., Zhang, M., & Schuck, P. (Eds.), Handbook of food powders: processes and properties. Woodhead Publishing, 285–338.

Gallardo, G., Guida, L., Martinez, V., López, M. C., Bernhardt, D., Blasco, R., Pedroza-Islas, R., & Hermida, L. G. (2013). Microencapsulation of linseed oil by spray drying for functional food application. Food Research International, 52(2), 473–482.

Gharsallaloui, A., Roudaut, G., Chambin, O., Voilley, A., & Saurel, R. (2007). Applications of spray-drying in microencapsulation of food ingredients: an overview. Food Research International, 40, 1107–1121.

Gogus, U., & Smith, C. (2010). n-3 Omega fatty acids: a review of current knowledge. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 45(3), 417–436.

Gouin, S. (2004). Microencapsulation: Industrial appraisal of existing technologies and trends. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 15, 330–347.

Goula, A. M., & Adamopoulos, K. G. (2012). A method for pomegranate seed application in food industries: seed oil encapsulation. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 90(4), 639–652.

Goyal, A., Sharma, V., Upadhyay, N., Gill, S., & Sihag, M. (2014). Flax and flaxseed oil: an ancient medicine & modern functional food. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 51(9), 1633–1653.

Goyal, A., Sharma, V., Upadhyay, N., Singh, A. K., Arora, S., Lal, D., & Sabikhi, L. (2015). Development of stable flaxseed oil emulsions as a potential delivery system of ω-3 fatty acids. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 52(7), 4256–4265.

Hedegaard R. V. & Skibsted L. H. (2013). Shelf-life of food powders. In: Bhandari, B., Bansal, N., Zhang, M., & Schuck, P. (Eds.), Handbook of food powders: processes and properties. Woodhead Publishing, 409–434.

Hogekamp, S., & Schubert, H. (2003). Rehydration of food powders. Food Science and Technology International, 9(3), 223–235.

Huang, H., Hao, S., Li, L., Yang, X., Cen, J., Lin, W., & Wei, Y. (2014). Influence of emulsion composition and spray-drying conditions on microencapsulation of tilapia oil. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 51(9), 2148–2154.

Huynh, T. V., Caffin, N., Dykes, G. A., & Bhandari, B. (2008). Optimization of the microencapsulation of lemon myrtle oil using response surface methodology. Drying Technology, 26(3), 357–368.

de Jong, J. A. H., Hoffmann, A. C., & Finkers, H. J. (1999). Properly determine powder flowability to maximize plant output. Chemical Engineering Progress, 95(4), 25–34.

Karaca, A. C., Nickerson, M., & Low, N. H. (2013). Microcapsule production employing chickpea or lentil protein isolates and maltodextrin: physicochemical properties and oxidative protection of encapsulated flaxseed oil. Food Chemistry, 139(1), 448–457.

Kim, E. H. J., Chen, X. D., & Pearce, D. (2002). Surface characterization of four industrial spray-dried dairy powders in relation to chemical composition, structure and wetting property. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 26(3), 197–212.

Kim, E. H. J., Chen, X. D., & Pearce, D. (2009). Surface composition of industrial spray-dried milk powders. 3. Changes in the surface composition during long-term storage. Journal of Food Engineering, 94(2), 182–191.

Kolanowski, W., Ziolkowski, M., Weißbrodt, J., Kunz, B., & Laufenberg, G. (2006). Microencapsulation of fish oil by spray drying—impact on oxidative stability. Part 1. European Food Research and Technology, 222(3–4), 336–342.

Nesterenko, A., Alric, I., Silvestre, F., & Durrieu, V. (2013). Vegetable proteins in microencapsulation: a review of recent interventions and their effectiveness. Industrial Crops and Products, 42, 469–479.

O’Kane, F. E., Happe, R. P., Vereijken, J. M., Gruppen, H., & van Boekel, M. A. J. S. (2004). Heat-induced gelation of pea legumin: comparison with soybean glycinin. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 52(16), 5071–5078.

Omar, K. A., Shan, L., Zou, X., Song, Z., & Wang, X. (2009). Effects of two emulsifiers on yield and storage of flaxseed oil powder by response surface methodology. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 8(9), 1316–1324.

Orlien, V., Andersen, A. B., Sinkko, T., & Skibsted, L. H. (2000). Hydroperoxide formation in rapeseed oil encapsulated in a glassy food model as influenced by hydrophilic and lipophilic radicals. Food Chemistry, 68(2), 191–199.

Østdal, H., Davies, M. J., & Andersen, H. J. (2002). Reaction between protein radicals and other biomolecules. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 33(2), 201–209.

Palzer, S. (2010). The relation between material properties and supra-molecular structure of water-soluble food solids. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 21(1), 12–25.

Samborska, K., Langa, E., Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A., & Witrowa-Rajchert, D. (2015). The influence of sodium caseinate on the physical properties of spray-dried honey. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 50(1), 256–262.

Schebor, C., Mazzobre, M. F., & del Pilar Buera, M. (2010). Glass transition and time-dependent crystallization behavior of dehydration bioprotectant sugars. Carbohydrate Research, 345(2), 303–308.

Serfert, Y., Drusch, S., & Schwarz, K. (2009). Chemical stabilisation of oils rich in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during homogenisation, microencapsulation and storage. Food Chemistry, 113(4), 1106–1112.

Sillick, M., & Gregson, C. M. (2010). Critical water activity of disaccharide/maltodextrin blends. Carbohydrate Polymers, 79(4), 1028–1033.

Soerensen, J. H., Krag, J., Pisecky, J., & Westegraard, V. (1978). Analytical methods for dry milk products. Denmark: A/S Niro Atomizer Copenhagen.

Szulc, K., & Lenart, A. (2016). Effect of composition on physical properties of food powders. International Agrophysics, 30(2), 237–243.

Thirundas, R., Gadhe, K. S., & Syed, I. H. (2014). Optimization of wall material concentration in preparation of flaxseed oil powder using response surface methodology. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 38(3), 889–895.

Thomsen, M. K., Lauridsen, L., Skibsted, L. H., & Risbo, J. (2005). Temperature effect on lactose crystallization, Maillard reactions, and lipid oxidation in whole milk powder. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 53(18), 7082–7090.

Tonon, R. V., Grosso, C. R., & Hubinger, M. D. (2011). Influence of emulsion composition and inlet air temperature on the microencapsulation of flaxseed oil by spray drying. Food Research International, 44(1), 282–289.

Tonon, R. V., Pedro, R. B., Grosso, C. R., & Hubinger, M. D. (2012). Microencapsulation of flaxseed oil by spray drying: effect of oil load and type of wall material. Drying Technology, 30(13), 1491–1501.

Tontul, I., & Topuz, A. (2013). Mixture design approach in wall material selection and evaluation of ultrasonic emulsification in flaxseed oil microencapsulation. Drying Technology, 31(12), 1362–1373.

Tontul, I., & Topuz, A. (2014). Influence of emulsion composition and ultrasonication time on flaxseed oil powder properties. Powder Technology, 264, 54–60.

Vega, C., Goff, H. D., & Roos, Y. H. (2007). Casein molecular assembly affects the properties of milk fat emulsions encapsulated in lactose or trehalose matrices. International Dairy Journal, 17(6), 683–695.

Westergaard, V. (2004). Milk powder technology: evaporation and spray drying. Niro A/S.

Xu, Y. Y., Howes, T., Adhikari, B., & Bhandari, B. (2012). Investigation of relationship between surface tension of feed solution containing various proteins and surface composition and morphology of powder particles. Drying Technology, 30(14), 1548–1562.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Domian, E., Brynda-Kopytowska, A. & Marzec, A. Functional Properties and Oxidative Stability of Flaxseed Oil Microencapsulated by Spray Drying Using Legume Proteins in Combination with Soluble Fiber or Trehalose. Food Bioprocess Technol 10, 1374–1386 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-017-1908-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-017-1908-1