Abstract

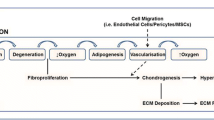

The formation of bone outside the endogenous skeleton is a significant clinical event, rendering affected individuals with immobility and a diminished quality of life. This bone, termed heterotopic ossification (HO), can appear in patients following invasive surgeries and traumatic injuries, as well as progressively manifest in several congenital disorders. A unifying feature of both genetic and nongenetic episodes of HO is immune system involvement at the early stages of disease. Activation of the immune system sets the stage for the downstream anabolic events that eventually result in ectopic bone formation, rendering the immune system a particularly appealing site of early therapeutic intervention for optimal management of disease. In this review, we will discuss the immunological contributions to HO disorders, with specific focus on contributing cell types, signaling pathways, relevant in vivo animal models, and potential therapeutic targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Alfieri KA, Forsberg JA, Potter BK. Blast injuries and heterotopic ossification. Bone Joint Res. 2012;1(8):192–7.

Bedi A, Zbeda RM, Bueno VF, et al. The incidence of heterotopic ossification after hip arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(4):854–63.

Cohn RM, Schwarzkopf R, Jaffe F. Heterotopic ossification after total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2011;40(11):E232–5.

Adegbite NS, Xu M, Kaplan FS, et al. Diagnostic and mutational spectrum of progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH) and other forms of GNAS-based heterotopic ossification. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(14):1788–96.

Kaplan FS, Xu M, Seemann P, et al. Classic and atypical fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) phenotypes are caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type I receptor ACVR1. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(3):379–90.

Pignolo RJ, Foley KL. Nonhereditary heterotopic ossification: implications for injury, arthroplasty, and aging. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2005;3(3–4):261–6.

Mitchell EJ, Canter J, Norris P, et al. The genetics of heterotopic ossification: insight into the bone remodeling pathway. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(9):530–3.

Forsberg JA, Pepek JM, Wagner S, et al. Heterotopic ossification in high-energy wartime extremity injuries: prevalence and risk factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(5):1084–91.

Scarlett RF, Rocke DM, Kantanie S, et al. Influenza-like viral illnesses and flare-ups of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;423:275–9.

Salisbury E, Rodenberg E, Sonnet C, et al. Sensory nerve induced inflammation contributes to heterotopic ossification. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(10):2748–58.

Yu PB, Deng DY, Lai CS, et al. BMP type I receptor inhibition reduces heterotopic [corrected] ossification. Nat Med. 2008;14(12):1363–9.

Hoff P, Rakow A, Gaber T, et al. Preoperative irradiation for the prevention of heterotopic ossification induces local inflammation in humans. Bone. 2013;55(1):93–101.

Evans KN, Forsberg JA, Potter BK, et al. Inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression is associated with heterotopic ossification in high-energy penetrating war injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(11):e204–13.

Kaplan FS, Shore EM, Gupta R, et al. Immunological features of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva and the dysregulated BMP4 pathway. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2005;3(3–4):189–93.

Forsberg JA, Potter BK, Polfer EM, et al. Do inflammatory markers portend heterotopic ossification and wound failure in combat wounds? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(9):2845–54.

Lanchoney TF, Cohen RB, Rocke DM, et al. Permanent heterotopic ossification at the injection site after diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunizations in children who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Pediatr. 1995;126(5 Pt 1):762–4.

Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Inherited human diseases of heterotopic bone formation. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(9):518–27.

Shore EM, Ahn J, Jan de Beur S, et al. Paternally inherited inactivating mutations of the GNAS1 gene in progressive osseous heteroplasia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):99–106.

Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, et al. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Genet. 2006;38(5):525–7.

Arron JR, Choi Y. Bone versus immune system. Nature. 2000;408(6812):535–6.

Alexander KA, Chang MK, Maylin ER, et al. Osteal macrophages promote in vivo intramembranous bone healing in a mouse tibial injury model. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(7):1517–32.

Ehrnthaller C, Huber-Lang M, Nilsson P, et al. Complement C3 and C5 deficiency affects fracture healing. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e81341.

Huber-Lang M, Kovtun A, Ignatius A. The role of complement in trauma and fracture healing. Semin Immunol. 2013;25(1):73–8.

Wu AC, Raggatt LJ, Alexander KA, et al. Unraveling macrophage contributions to bone repair. Bonekey Rep. 2013;2:373.

Charles JF, Nakamura MC. Bone and the innate immune system. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2014;12(1):1–8.

De Benedetti F, Rucci N, Del Fattore A, et al. Impaired skeletal development in interleukin-6-transgenic mice: a model for the impact of chronic inflammation on the growing skeletal system. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(11):3551–63.

Bonar SL, Brydges SD, Mueller JL, et al. Constitutively activated NLRP3 inflammasome causes inflammation and abnormal skeletal development in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35979.

Hardy R, Cooper MS. Bone loss in inflammatory disorders. J Endocrinol. 2009;201(3):309–20.

Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):240–73. Table of Contents.

Boehm T. Design principles of adaptive immune systems. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(5):307–17.

Borthwick LA, Wynn TA, Fisher AJ. Cytokine mediated tissue fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832(7):1049–60.

Ishida Y, Gao JL, Murphy PM. Chemokine receptor CX3CR1 mediates skin wound healing by promoting macrophage and fibroblast accumulation and function. J Immunol. 2007;180(1):569–79.

Tidball JG. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288(2):R345–53.

Kan L, Lounev VY, Pignolo RJ, et al. Substance P signaling mediates BMP-dependent heterotopic ossification. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(10):2759–72. This study is the first to show that chemical inhibition of mast cells and Substance P signaling significantly reduces HO formation in vivo and provides a link between elevated Substance P levels in FOP patients and HO development.

Kan L, Mutso AA, McGuire TL, et al. Opioid signaling in mast cells regulates injury responses associated with heterotopic ossification. Inflamm Res. 2014;63(3):207–15. This study further elucidated the role of mast cells and their signaling pathways in the development of HO.

Kan L, Liu Y, McGuire TL, et al. Dysregulation of local stem/progenitor cells as a common cellular mechanism for heterotopic ossification. Stem Cells. 2009;27(1):150–6.

Champagne CM, Takebe J, Offenbacher S, et al. Macrophage cell lines produce osteoinductive signals that include bone morphogenetic protein-2. Bone. 2002;30(1):26–31.

Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(12):958–69.

Mohler ER, Gannon F, Reynolds C, et al. Bone formation and inflammation in cardiac valves. Circulation. 2001;103(11):1522–8.

Gannon FH, Glaser D, Caron R, et al. Mast cell involvement in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Hum Pathol. 2001;32(8):842–8.

Di Paolo N, Sacchi G, Lorenzoni P, et al. Ossification of the peritoneal membrane. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24(5):471–7.

Smith RS, Smith TJ, Blieden TM, et al. Fibroblasts as sentinel cells. Synthesis of chemokines and regulation of inflammation. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(2):317–22.

Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, et al. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(9):785–97.

Ignatius A, Schoengraf P, Kreja L, et al. Complement C3a and C5a modulate osteoclast formation and inflammatory response of osteoblasts in synergism with IL-1beta. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(9):2594–605.

Tsuji T, Nakamura S, Komuro I, et al. A living case of pulmonary ossification associated with osteoclast formation from alveolar macrophage in the presence of T-cell cytokines. Intern Med. 2003;42(9):834–8.

Chakkalakal SA, Zhang D, Culbert AL, et al. An Acvr1 R206H knock-in mouse has fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(8):1746–56. The first publication of an Alk2 (R206H) knock-in mouse model of HO, resulting in very strong recapitulation of the human disease.

Hegyi L, Gannon FH, Glaser DL, et al. Stromal cells of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva lesions express smooth muscle lineage markers and the osteogenic transcription factor Runx2/Cbfa-1: clues to a vascular origin of heterotopic ossification? J Pathol. 2003;201(1):141–8.

Kan L, Hu M, Gomes WA, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing BMP4 develop a fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP)-like phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(4):1107–15.

Mills CD. M1 and M2 macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Crit Rev Immunol. 2012;32(6):463–88.

Bischoff SC. Role of mast cells in allergic and non-allergic immune responses: comparison of human and murine data. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(2):93–104.

Frieri M, Patel R, Celestin J. Mast cell activation syndrome: a review. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13(1):27–32.

Douaiher J, Succar J, Lancerotto L, et al. Development of mast cells and importance of their tryptase and chymase serine proteases in inflammation and wound healing. Adv Immunol. 2014;122:211–52.

Ehrlich HP. A snapshot of direct cell-cell communications in wound healing and scarring. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013;2(4):113–21.

Rodewald HR, Feyerabend TB. Widespread immunological functions of mast cells: fact or fiction? Immunity. 2012;37(1):13–24.

Vincent L, Vang D, Nguyen J, et al. Mast cell activation contributes to sickle cell pathobiology and pain in mice. Blood. 2013;122(11):1853–62.

Oldford SA, Marshall JS. Mast cells as targets for immunotherapy of solid tumors. Mol Immunol. 2014.

Heron A, Dubayle D. A focus on mast cells and pain. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;264(1–2):1–7.

Farrugia BL, Whitelock JM, Jung M, et al. The localisation of inflammatory cells and expression of associated proteoglycans in response to implanted chitosan. Biomaterials. 2014;35(5):1462–77.

Thevenot PT, Baker DW, Weng H, et al. The pivotal role of fibrocytes and mast cells in mediating fibrotic reactions to biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2011;32(33):8394–403.

Galli SJ, Grimbaldeston M, Tsai M. Immunomodulatory mast cells: negative, as well as positive, regulators of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(6):478–86.

Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. New developments in mast cell biology. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(11):1215–23.

Gri G, Frossi B, D’Inca F, et al. Mast cell: an emerging partner in immune interaction. Front Immunol. 2012;3:120.

Bucelli RC, Gonsiorek EA, Kim WY, et al. Statins decrease expression of the proinflammatory neuropeptides calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P in sensory neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324(3):1172–80.

Salisbury E, Sonnet C, Heggeness M, et al. Heterotopic ossification has some nerve. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2010;20(4):313–24.

Overed-Sayer C, Rapley L, Mustelin T, et al. Are mast cells instrumental for fibrotic diseases? Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:174.

Monument MJ, Hart DA, Befus AD, et al. The mast cell stabilizer ketotifen reduces joint capsule fibrosis in a rabbit model of post-traumatic joint contractures. Inflamm Res. 2012;61(4):285–92.

Litman GW, Rast JP, Fugmann SD. The origins of vertebrate adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(8):543–53.

Brocker C, Thompson D, Matsumoto A, et al. Evolutionary divergence and functions of the human interleukin (IL) gene family. Hum Genomics. 2010;5(1):30–55.

Fensterl V, Sen GC. Interferons and viral infections. Biofactors. 2009;35(1):14–20.

Gannon FH, Valentine BA, Shore EM, et al. Acute lymphocytic infiltration in an extremely early lesion of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;346:19–25.

Kaplan FS, Glaser DL, Shore EM, et al. Hematopoietic stem-cell contribution to ectopic skeletogenesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(2):347–57.

Egan KP, Kim JH, Mohler 3rd ER, et al. Role for circulating osteogenic precursor cells in aortic valvular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(12):2965–71.

Rifas L. T-cell cytokine induction of BMP-2 regulates human mesenchymal stromal cell differentiation and mineralization. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98(4):706–14.

Carr MW, Roth SJ, Luther E, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 acts as a T-lymphocyte chemoattractant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(9):3652–6.

Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29(6):313–26.

Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(3):206–16.

Chamberlain G, Wright K, Rot A, et al. Murine mesenchymal stem cells exhibit a restricted repertoire of functional chemokine receptors: comparison with human. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e2934.

Sordi V, Malosio ML, Marchesi F, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells express a restricted set of functionally active chemokine receptors capable of promoting migration to pancreatic islets. Blood. 2005;106(2):419–27.

Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol. 2008;214(2):199–210.

Kaviratne M, Hesse M, Leusink M, et al. IL-13 activates a mechanism of tissue fibrosis that is completely TGF-independent. J Immunol. 2004;173(6):4020–9.

Culbert AL, Chakkalakal SA, Theosmy EG, et al. Alk2 regulates early chondrogenic fate in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva heterotopic endochondral ossification. Stem Cells. 2014;32(5):1289–300. This study utilized in vitro and in vivo approaches to demonstrate the molecular role of Alk2 in the chondrogenesis stage of HO in FOP.

Akdis M, Burgler S, Crameri R, et al. Interleukins, from 1 to 37, and interferon-gamma: receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):701–21. e1-70.

Tsai PT, Lee RA, Wu H. BMP4 acts upstream of FGF in modulating thymic stroma and regulating thymopoiesis. Blood. 2003;102(12):3947–53.

Detmer K, Steele TA, Shoop MA, et al. Lineage-restricted expression of bone morphogenetic protein genes in human hematopoietic cell lines. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1999;25(5–6):310–23.

Sivertsen EA, Huse K, Hystad ME, et al. Inhibitory effects and target genes of bone morphogenetic protein 6 in Jurkat TAg cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(10):2937–48.

MacDonald KM, Swanstrom MM, McCarthy JJ, et al. Exaggerated inflammatory response after use of recombinant bone morphogenetic protein in recurrent unicameral bone cysts. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(2):199–205.

Cunningham NS, Paralkar V, Reddi AH. Osteogenin and recombinant bone morphogenetic protein 2B are chemotactic for human monocytes and stimulate transforming growth factor beta 1 mRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(24):11740–4.

Kaplan FS, Shen Q, Lounev V, et al. Skeletal metamorphosis in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26(6):521–30.

Shimono K, Tung WE, Macolino C, et al. Potent inhibition of heterotopic ossification by nuclear retinoic acid receptor-gamma agonists. Nat Med. 2011;17(4):454–60. This study documents potent in vivo inhibition of HO by administration with retinoic acid receptor-gamma agonists, identifying a new potential therapeutic target for the treatment of HO disorders.

Vavken P, Castellani L, Sculco TP. Prophylaxis of heterotopic ossification of the hip: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(12):3283–9.

Jee WS, Ma YF. The in vivo anabolic actions of prostaglandins in bone. Bone. 1997;21(4):297–304.

Grohs JG, Schmidt M, Wanivenhaus A. Selective COX-2 inhibitor versus indomethacin for the prevention of heterotopic ossification after hip replacement: a double-blind randomized trial of 100 patients with 1-year follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(1):95–8.

Van Rooijen N. The liposome-mediated macrophage ‘suicide’ technique. J Immunol Methods. 1989;124(1):1–6.

Ferenbach DA, Sheldrake TA, Dhaliwal K, et al. Macrophage/monocyte depletion by clodronate, but not diphtheria toxin, improves renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Kidney Int. 2012;82(8):928–33.

Summan M, Warren GL, Mercer RR, et al. Macrophages and skeletal muscle regeneration: a clodronate-containing liposome depletion study. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290(6):R1488–95.

Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Kupffer cell depletion by liposome-delivered drugs: comparative activity of intracellular clodronate, propamidine, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Hepatology. 1996;23(5):1239–43.

Barrera P, Blom A, van Lent PL, et al. Synovial macrophage depletion with clodronate-containing liposomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(9):1951–9.

O’Connor TM, O’Connell J, O’Brien DI, et al. The role of substance P in inflammatory disease. J Cell Physiol. 2004;201(2):167–80.

Manak MM, Moshkoff DA, Nguyen LT, et al. Anti-HIV-1 activity of the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant and synergistic interactions with other antiretrovirals. AIDS. 2010;24(18):2789–96.

Juurikivi A, Sandler C, Lindstedt KA, et al. Inhibition of c-kit tyrosine kinase by imatinib mesylate induces apoptosis in mast cells in rheumatoid synovia: a potential approach to the treatment of arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(8):1126–31.

Werner CM, Zimmermann SM, Wurgler-Hauri CC, et al. Use of imatinib in the prevention of heterotopic ossification. HSS J. 2013;9(2):166–70. Administration of imatinib, resulting in blockage of PDGF signaling, reduced HO volume by 85% in an Achilles tenotomy mouse model of HO, documenting an additional approach by which to therapeutically intervene in cases of HO.

Sathish JG, Sethu S, Bielsky MC, et al. Challenges and approaches for the development of safer immunomodulatory biologics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(4):306–24.

Zalevsky J, Secher T, Ezhevsky SA, et al. Dominant-negative inhibitors of soluble TNF attenuate experimental arthritis without suppressing innate immunity to infection. J Immunol. 2007;179(3):1872–83.

Rau R. Adalimumab (a fully human anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody) in the treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis: the initial results of five trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(2):ii70–3.

Mohedas A, Wang Y, Sanvitale CE, et al. Structure-activity relationship of 3,5-diaryl-2-aminopyridine ALK2 inhibitors reveals unaltered binding affinity for fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva causing mutants. J Med Chem. 2014.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through the Center for Research in FOP and Related Disorders, the International FOP Association (IFOPA), the Ian Cali Endowment, the Weldon Family Endowment, the Progressive Osseous Heteroplasia Association (POHA), the Isaac and Rose Nassau Professorship (to FSK), the Cali/Weldon Professorship (to EMS), and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-AR41916 and R01-AR046831).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

MR Convente, H Wang, RJ Pignolo, FS Kaplan, and EM Shore all declare no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All studies by the authors involving animal and/or human subjects were performed after approval by the appropriate institutional review boards. When required, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Skeletal Development

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Convente, M.R., Wang, H., Pignolo, R.J. et al. The Immunological Contribution to Heterotopic Ossification Disorders. Curr Osteoporos Rep 13, 116–124 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-015-0258-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-015-0258-z