Abstract

The integration of antiretroviral therapy (i.e., ART) into HIV care has dramatically extended the life expectancy of those living with HIV. However, in comparison to similar HIV-uninfected populations, HIV-infected persons experience an excess of morbidity and mortality with an early onset of aging complications including neurocognitive decline, osteoporosis, impaired physical function, frailty, and falls. Recent consensus guidelines encourage clinicians and researchers to consider functional impairment of HIV-infected adults as a measure to understand the impact of aging across a range of abilities. Despite the importance of assessing function in persons aging with HIV infection, a lack of consistent terminology and standardization of assessment tools has limited the application of functional assessments in clinical or research settings. Herein, we distinguish between different approaches used to assess function, describe what is known about function in the aging HIV population, and consider directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

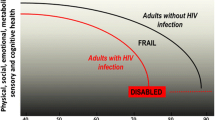

The demographics of the HIV epidemic are changing and currently, approximately one-half of the people living with HIV in the United States are age 50 or older [1]. The high priority on understanding the interaction between age and HIV infection is illustrated by a recent summary report from the HIV and Aging Consensus Project [2••]. In comparison to similar HIV-uninfected populations, HIV-infected persons, even when on effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), experience an excess of morbidity and mortality [3, 4]. Persons on ART have early onset of aging complications including neurocognitive decline [5], osteoporosis and fractures [6–8], impaired physical function [9–11], frailty [12–16], and falls [17]. Thus, over the past decade, the focus of HIV management has gradually shifted from management of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) complications to the management of chronic non-infectious co-morbidities in an increasingly older and more complex patient population.

In geriatric medicine, the overarching goals of care for older adults include the prevention of functional decline, maintenance of independence, and preserved health-related quality of life (HR-QoL). Prevention of functional decline is an important component of independence and HR-QoL [18], and functional limitations are strong predictors of disability, nursing home admission, and death [19]. Indeed, some geriatricians have proposed that assessment of functional status should be routinely included in the clinical assessment as a “sixth vital sign” [20]. The functional complications of aging were first identified as a priority area in HIV and aging research following the observation of an increased prevalence of a frailty-related phenotype in HIV-infected men from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) [12]. In a recent report published by the Office of AIDS Research, the importance of understanding the pathophysiology of physical function and frailty was again identified as a high priority topic [21••]. Experts in the field have encouraged clinicians and researchers to consider functional capacity as a measure to understand the impact of aging across a range of abilities [2••, 21••, 22, 23].

Despite the importance of function in aging persons with or without HIV infection, the concept of “function” and the terminology used to describe its multiple dimensions may be confusing. The terms “functional limitations”, “functional impairment”, “comorbidity”, “quality of life”, “disability”, and “frailty” are often used interchangeably to describe dynamically different processes among aging adults. The goals of this review are to: (i) distinguish between different terms used to describe function and the corresponding measures, (ii) describe what is known about function in the aging HIV population, and (iii) consider directions for future research in aging with HIV infection.

Functional Impairment and Disability

The Disablement Model originally conceptualized by Nagi and extended by Verbrugge and Jette links pathology, physical impairment, functional limitation, and disability [24, 25]. According to this model, an underlying pathology may lead to an “impairment” at the tissue, organ, or body system level, which results in a “functional limitation”, and can lead ultimately to “disability” (Fig. 1). For example: a prior injury (pathology) results in arthritis of the knee (impairment), slow gait speed and difficulty rising from a chair (limitations), and eventual confinement to a wheelchair (disability).

In research settings, functional limitations are typically assessed via self-report or objective, standardized tests of physical performance that are predictive of subsequent disability and mortality. These tests include, among others, short gait speed (over 4-6 meters), longer corridor walk (typically 400 meters or distance covered in 6 minutes), a short physical performance battery (SPPB), and the timed-up and go test [26–29, 30•, 31, 32]. Because these tests are measured in controlled settings, functional measurements may not include environmental influences that determine the impact of the functional limitation on the day-to-day activities of older adults.

“Disability” describes the difficulty or dependency in carrying out activities in the environment. Thus disability is a social phenomenon in which the ability to complete a task is dependent upon what is expected of an individual within the social, cultural, and physical environment, and dependent upon the individual’s ability to cope with the underlying impairment [33]. Rather than the controlled tests of specific functional limitations, disability is subjective and is typically assessed by self-report of difficulty in completing specific tasks. Commonly used assessment methods include questionnaires targeting difficulty or dependency in completing one or more independent activities of daily living (IADLs) or activities of daily living (ADLs). IADLs assess higher level physical and cognitive functioning including medication and finance management, meal preparation, shopping, transportation arrangement, and telephone use [34], while ADLs include more basic functions of dressing, bathing, toileting or continence, transferring, and feeding [35]. Importantly, the model of disability is a dynamic process that reflects changes in both the individual and the environment. For example, disability following a hip fracture may improve with physical therapy, although the prior level of function is often not attainable [24].

In an attempt to standardize definitions of disability and functional limitation, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) framework was developed in 2001 [36–38]. Despite an emphasis on routine use of the ICF framework by international agencies, uptake in the US, particularly in research studies, has been limited. The ICF describes function in separate domains of cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities, and participation through a standardized WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS; version 2.0). The assessment is applicable across cultures, provides a direct conceptual link to the ICF, and takes between 5-20 minutes to administer or complete [38, 39].

Many studies use a self-report of HR-QoL as a measure of self-reported functional limitations or disability. Although HR-QoL also encompasses the impact of disease or injury on limitations, functional state, and participation in activity, the focus is on the individual’s values and expectations rather than the impairment [40]. Thus, discrepancies between performance-based and self-reported measures are frequently reported [41–43]. For example, in the Groningen Longitudinal Aging Study, subjects with more depressive symptoms and those with lower levels of perceived physical competence were more likely to underestimate self-reported functioning [44]. Furthermore, older adults with HIV-infection diagnosed early in the AIDS era represent a survival cohort who may have a higher threshold for reporting functional limitations [45]. The ability to complete a task is influenced by what an individual can do (capability), what an individual wants to do (motivation), and what an individual believes they can do (perception) [41]. Although both performance based- and self-reported measures encompass capability, motivation, and perception to an extent, performance-based measures emphasize capability (often in a controlled testing environment) while self-reported measures assess the perception of one’s ability to accomplish tasks in his or her living environment and self-efficacy questionnaires assess an individual’s motivation.

Functional Impairment and Disability among Adults Aging with HIV Infection

Functional impairments in HIV/AIDS were initially reported in association with AIDS or AIDS wasting syndrome, most often found among persons with high HIV-1 RNA or CD4 count <200 cells/μL. Over the last two decades, multiple objective tools to assess functional impairments have been used in the clinical and research settings to identify subtle to overt differences in exercise tolerance, grip strength, balance, gait speed, and chair rise time among people with HIV. Results of these studies are summarized in Table 1. Although these studies have made important contributions to our understanding of the functional impairment and disability process in people with HIV infection, methodological differences limit comparisons between studies or to other studies of HIV-uninfected cohorts. For example, gait speed has been measured over courses of 2.4 meters, 3.33 meters, 8 meters, 30 feet, 400 meters, or by distance walked in 6 minutes.

Self-report of physical function has also been used to assess functional impairments in HIV infection. The MACS and Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) used self-report to compare function in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected subjects with similar behavioral risk and similar demographics, and thus limited many of the recognized and unrecognized confounding variables encountered when matching HIV-infected to national cohorts or smaller cohorts of HIV-uninfected subjects. Among 1800 men from the MACS, self-reported physical function from the short form (SF)-36 physical function domains was significantly worse among HIV-infected persons and associated with lower CD4 count or AIDS, white race, and a trend toward higher glucose. In multivariate models, lower physical function was a risk factor for diabetes [46, 47]. In the VACS, self-reported physical function was not significantly different between 889 HIV-infected and 647 HIV-uninfected veterans. Although increased age was associated with impaired physical function in both HIV-infected and uninfected subjects, comorbidity was a stronger predictor of self-reported function and disability than age [48]. Among 262 HIV-infected and uninfected older and younger adults from the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program, greater comorbid burden was a stronger predictor of both self-reported physical and mental function than HIV status or age [49].

Increased risk of disability in HIV was recognized early in the AIDS epidemic. One of the largest early studies to address disability in the pre-ART era (1988-1991) included 728 patients: 14 % reported difficulties in IADLs only and 4 % in both ADLs and IADLs. Dependency in IADLs or ADLs was strongly associated with AIDS diagnosis and lower CD4 counts. In regression models including CD4 and AIDS diagnosis, ADL or IADL dependency was associated with a significantly shorter survival time [50].

Several studies have investigated associations between disability and HIV in the era of effective ART. In a survey of HIV-infected adults in British Columbia in the ART era, 92 % of 614 participants reported at least one impairment and one-third had more than ten impairments. Activity limitations were reported by 81 % and participation restrictions by 93 %, with significantly greater restrictions among persons with CD4 < 200 compared to >500 cells/ μL. High rates of self-reported depression were closely associated with social role restriction [51]. Among nearly 800 HIV-infected subjects in the United Kingdom (mean age of 40.4 years), 28 % reported difficulty with mobility, 19 % difficulty with self-care, and 38 % difficulty with usual activities. Health status decreased with increasing age, lower education, and unemployment, and was much lower among those with CD4 < 200 cells/μL or VL >50 copies/mL [52]. In a smaller study of 179 subjects including four groups of younger and older, HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected persons, age and HIV status had synergistic effects on IADLs and ADLs; HIV but not age had an independent main effect on both measures [53]. In a cohort of over 1900 patients at the University of Alabama (median age 43.6 years), self-reported impairments in mobility, usual activities, and self-care were significantly associated with pain, mood, and older age [54]. In summary, even in the ART era, dependence in IADLs or ADLs appears to exceed that observed in HIV-uninfected persons and is strongly associated with AIDS or low CD4 T-cell count and depression.

Frailty

In contrast to disability, frailty is a geriatric syndrome caused by dysregulation in multiple physiologic systems including immunologic, endocrine, hematologic, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular [55, 56]. Using the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort, Linda Fried operationalized five components commonly recognized in frailty (slowness, weakness, shrinking, low levels of activity, and exhaustion) to validate one of the most commonly used indices [55, 57]. The frailty phenotype is associated with high vulnerability for adverse health outcomes including hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality [33, 58, 59]. The presence of multiple deficits acts synergistically to increase an individual’s vulnerability to illness or hospitalization [55, 60]. Variations of Fried's frailty phenotype are used throughout the geriatric literature, but often substitute the tools used to assess one of the components, use different population cut-points to determine the frail threshold, or may use less than the five components. Thus, the definition of frailty can vary across studies. Additionally, the overlap between the frailty components and depression symptoms and lack of a neurocognitive assessment may limit the sensitivity and specificity of Fried’s frailty phenotype in some populations [61, 62]. Other definitions of frailty have been tested with variable uptake in the clinical and research setting and include: the Tilburg Frailty Indicator [63], the Groningen Frailty Indicator [64], the Edmonton Frail Scale [65], the FRAIL scale [66], and the more commonly used Frailty Index introduced by Rockwood, et al. [67–70]. Despite over a decade of experience in using the frailty phenotype first described by Fried et al., the best way to assess and measure frailty is still debated among geriatricians [58, 61, 70–73].

Frailty among Adults Aging with HIV Infection

The immunologic and phenotypic similarities observed in both frailty and AIDS were first brought to attention by investigators from the MACS in 1992 [74]. To further explore these similarities, data from the MACS were used to create a frailty related phenotype, approximating four of the five domains of Fried's frailty phenotype. A strong association was observed between HIV infection and the MACS frailty-related phenotype with findings most pronounced among men with low CD4 lymphocyte count (<350 cells/μL), high viral load (≥100,000 copies/mL), clinically defined AIDS, longer duration of HIV infection and older age [12]. A subsequent study in this population found a markedly higher prevalence of a frailty-related phenotype in the pre-ART era (1994-1995) among individuals with AIDS (24 %) compared to the post-ART era, 2000-2005 (10 %), or compared to persons without AIDS in the pre- or post-ART era (3.3 % and 2.9 %, respectively). The authors estimated that a decrease of CD4 lymphocyte count of 250 cells/μL and a 10 year increase in age had similar effects on the prevalence of the frailty-related phenotype [14]. Furthermore, an increased risk of subsequent AIDS or mortality was observed among men without AIDS when the frailty-related phenotype was sustained over at least two visits [13]. In 2007, the MACS introduced the 4-m walk into study visits, allowing for the use of Fried’s five component frailty phenotype rather than the frailty-related phenotype. In a subsequent study using Fried’s frailty phenotype, those with frailty at one or more visits were more likely to have HIV infection, a history of AIDS, lower CD4 lymphocyte count, and less likely to have an undetectable viral load. Furthermore, HIV-infected men were more likely to manifest frailty at multiple study visits in comparison to HIV-uninfected men, and those with both HIV and AIDS were more likely to convert from a non-frail to frail phenotype [75•].

The association between frailty and low CD4 lymphocyte count or an AIDS diagnosis has been replicated in other cohorts. In the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), frailty was higher among HIV-infected women with AIDS (12 %) or a CD4 lymphocyte count <100 cells/μL (20 %), compared to HIV-uninfected women (8 %), HIV-infected women without AIDS (7 %), or HIV-infected women with CD4 count ≥ 500cells/μL (6 %) [16]. Among intravenous drug users in the AIDS Linked to the IntraVenous Experience (ALIVE) Cohort, 14.5 % of the HIV-infected participants were frail compared with 11.4 % of the HIV-uninfected participants. Of note, this is the only study that has shown that presence of the frailty phenotype in HIV-infected persons is associated with an increased mortality risk independent of HIV infection. Importantly, the impact of both HIV infection and frailty had a synergistic effect on mortality (mortality OR = 2.6 with HIV infection; OR = 3.3 with frailty; and OR = 7.1 with both HIV and frailty) [76•].

Other studies have reported a prevalence of frailty between 5-33 % among HIV-infected persons in routine HIV care [15, 77–80]. In the Washington University Infectious Diseases Clinic, frailty was associated with older age, low current and nadir CD4 count and longer time since HIV diagnosis, lower albumin, greater comorbidity and depression, more hospitalizations, and unemployment [15]. Similar findings were observed in the Study to Understand the National History of HIV/AIDS (SUN Study), where 5 % of participants were frail, and frailty was associated with hepatitis C, depression, older age, unemployment, and a history of opportunistic infection [77]. In another cohort, of 359 patients receiving care for HIV infection, 27 (8 %) met frailty criteria by Fried's frailty phenotype, and the odds for frailty increased with the number of comorbidities (most notably psychiatric disease, chronic pain, and viral hepatitis), lower physical activity, smoking, and lack of employment. Although frailty was associated with CD4 count <200 cells/μL, no association was noted between frailty and age [9].

One of the first reports of frailty in an African setting evaluated 504 subjects (216 HIV-infected on ART, 32 HIV-infected not on ART, and 256 HIV-uninfected) from Cape Town. Frailty by Fried’s criteria was highest in the HIV-infected cohort not on ART (28 %) in comparison to those on ART (18 %) and HIV-uninfected (13 %). Among ART-treated individuals, lower CD4 count (<500 cells/μL) and lower body mass index (BMI) were associated with frailty [80].

In summary, overlap between HIV and frailty have been recognized since early in the AIDS epidemic, and frailty continues to be most frequently recognized among HIV-infected persons not on ART, with low CD4 t-cell count, or high HIV-1 RNA. Variations in the frailty definition limit the comparisons of frailty prevalence between study populations, however the factors consistently associated with frailty can lead to a greater understanding of the pathophysiology and potential interventions in HIV-infected populations.

Are Functional Impairment, Disability, and Frailty Measures Interchangeable?

Although often overlapping, disability and frailty can differ greatly with respect to pathophysiology, prognosis, and treatment of impairment [33]. Although functional status and frailty are both predictors of poor outcomes, and frail persons often show functional limitations, frailty is a state of heightened vulnerability marked by more than simply a decline in function (Fig. 1) [81]. Some authors consider frailty a “pre-disability” state, in which a stressor can trigger the progression to disability [81, 82]. Although one can return to the pre-disability state, function rarely achieves previous levels experienced. Functional limitations and subsequent disability are often the result of expected aging complications (i.e., arthritis), and management may include rehabilitation therapy to regain function or minimize limitations and assistive devices to enable completion of activities, thereby preventing further decline and social isolation [33]. In contrast, frailty requires an investigation into potential underlying causes of weakness, weight loss, and poor exercise tolerance, with interventions focused on minimizing further loss of weight and muscle through resistance training, nutritional supplementation, and cardiovascular rehabilitation. Similar to disability, frailty may have social or environmental influences including access to food, physical inactivity, and depression. Interventions to improve functional limitations, disability, or frailty may all improve quality of life, with further enhancement provided through mental health care, improved social support networks, and spiritual support [33].

To illustrate the distinction between functional limitations and frailty, we compared the SPPB to the classification of frailty by Fried’s phenotype in 359 HIV-infected persons on ART. Among the 27 persons that were identified as frail, less than one-half had significant impairment on the short physical performance battery (SPPB, score <9), and four had a perfect score [9]. Conversely, of the 26 persons with significant impairment on the SPPB (score <9), three were non-frail, ten were pre-frail, and 13 were frail. The modest agreement across instruments can be explained, in part, by the characteristics of the assessments: the frailty phenotype is a global assessment with subjective components that overlap with depressive symptoms, whereas the SPPB focuses on lower extremity function [9, 30•, 55, 61, 83–85]. These results support the consensus that frailty and functional impairments or disability are complementary, but not interchangeable, constructs.

Future Directions

Measurement of functional impairment, disability, or frailty in the clinical assessment of HIV-infected persons is invaluable in understanding the current needs and future prognosis of persons aging with HIV. These assessments, however, require a time commitment from both the provider and the patient. Thus, identifying the most effective tools for use in clinical and research settings is important to understand and meet the needs of those aging with HIV.

As tools to assess function, disability and frailty are already routinely used in the clinical and research settings in geriatrics and gerontology, we propose that they should have similar application in HIV care and research. Accordingly, research is needed to identify the measures of impairment, disability, and/or frailty that may be most appropriately and effectively applied in the evaluation of persons aging with HIV. Useful measures could include a stand-alone assessment such as gait speed, or may complement other risk assessment tools in HIV, such as the VACS Index [86]. Similar to the development of the VACS Index, we should consider a tool that is simple, cost-effective, requires minimal time and effort from clinicians, and provides a valid assessment of the outcome of interest [86]. In this context, we propose several considerations for the development, use, and interpretation of functional and frailty assessments.

First, we should recognize that the tools used in the clinical setting and research settings may be different, with the outcome of interest determining the appropriate tool. If the need is to evaluate a patient for home health needs or nursing home placement, an assessment of dependency in IADLs or ADLs should be used. For a research study designed to understand the pathophysiology of weakness during aging with HIV infection, a standardized, objective measurement of strength without the influence of the environment (i.e., chair-rise-time or grip strength) would be an appropriate tool. Second, consideration should be given to whether tools should predict outcomes specifically in HIV-infected persons, or if more general tools should be implemented. For instance, as described above, in prior studies utilizing Fried's frailty phenotype or a frailty-like phenotype (e.g., MACS), frailty in the HIV-infected persons was consistently associated with low CD4 count, high viral load, and depressive symptoms. A tool to identify frailty that considers HIV-specific factors or depressive symptoms could be a more specific and sensitive predictor of vulnerability among HIV-infected persons. Third, to the extent possible, standardized tools should be implemented and interpreted using standardized criterion so that outcomes can easily be compared across clinical and research settings. Varying definitions between studies limit the generalizability and reduce the ability to compare or combine findings from different study populations. Use of standardized tools that are used in large aging cohorts (i.e., the SPPB in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging) may allow for comparison to a standard norm of healthy aging adults.

Importantly, tools for assessing and measuring function, disability, and frailty must be tested and validated as predictors of relevant outcomes (i.e., hospitalization, morbidity, mortality) in HIV-infected populations. The frailty assessment validated in the Cardiovascular Health Study was developed to predict hospitalizations, institutionalization, and mortality in a general population older than 65 and is thought to serve as a more important prognostic tool in persons 80 years or older [87], thus use of this tool in a younger HIV-infected population with different comorbidities to predict similar outcomes should first be established. Similarly, the SPPB is a standardized, objective assessment of lower extremity performance established in an elderly population that may be limited by a ceiling effect in younger individuals with higher level of performance. For studies of younger HIV-infected persons, consideration should be given to use of an expanded version of the SPPB which has been previously proposed for use in younger persons [88]. The modifications improve discrimination of physical function at the higher end of the functional spectrum. We are currently validating these tests in a larger population for prediction of clinical outcomes such as falls, fall-related injuries, hospitalizations, and deaths.

Lastly, consideration should be given to the routine use of a measure of functional impairment, disability, or frailty as outcomes in clinical trials in HIV infection. For example, in an interventional trial of a new ART agent or a therapy to decrease immune activation or inflammation, a change in chair rise ability or gait speed would provide an inexpensive, clinically relevant, easily obtainable measure of benefit or harm from an investigational therapy.

Conclusions

As the focus of HIV management has shifted to the management of chronic non-infectious co-morbidities in an increasingly older and more complex population, ascertainment of an individual’s ability to maintain independence is of increasing importance. Both functional limitations and frailty are strong predictors of subsequent disability, loss of independence and death. Variations in the tools, and their application, limit the comparisons that can be made across and between studies. Identification of the most appropriate tools for the outcomes of interest, and validation and standardization of the tools in a population of middle-aged and older HIV-infected adults, will improve the usefulness of functional and frailty assessments at the bedside and in the research setting.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, Halter JB, Hazzard WR, Horne FM, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:542–53.

Summary report from the Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Aging Consensus Project: treatment strategies for clinicians managing older individuals with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012,60:974-979. This is a nice summary of the key points from the HIV and Aging Consensus Project document and highlights issues in clinical care and research priorities.

Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, Menozzi M, Carli F, Garlassi E, et al. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1120–6.

Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 2008,372:293-299.

Sacktor N, Skolasky RL, Cox C, Selnes O, Becker JT, Cohen B, et al. Longitudinal psychomotor speed performance in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive individuals: impact of age and serostatus. J Neurovirol. 2010;16:335–41.

Womack JA, Goulet JL, Gibert C, Brandt C, Chang CC, Gulanski B, et al. Increased risk of fragility fractures among HIV infected compared to uninfected male veterans. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17217.

Young B, Dao CN, Buchacz K, Baker R, Brooks JT. Increased rates of bone fracture among HIV-infected persons in the HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) compared with the US general population, 2000-2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1061–8.

Walker Harris V, Brown TT. Bone loss in the HIV-infected patient: evidence, clinical implications, and treatment strategies. J Infect Dis. 2012;205 Suppl 3:S391–8.

Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Jankowski CM, Duong S, Mawhinney S, Kohrt WM, et al. Comparison of functional status instruments in HIV-infected adults on effective antiretroviral therapy. HIV Clin Trials. 2012;13:324–34.

Oursler KK, Sorkin JD, Smith BA, Katzel LI. Reduced aerobic capacity and physical functioning in older HIV-infected men. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:1113–21.

Richert L, Dehail P, Mercie P, Dauchy FA, Bruyand M, Greib C, et al. High frequency of poor locomotor performance in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2011;25:797–805.

Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, Phair JP, Jamieson BD, Holloway M, et al. HIV-1 infection is associated with an earlier occurrence of a phenotype related to frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1279–86.

Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, Phair JP, Jamieson BD, Holloway M, et al. A frailty-related phenotype before HAART initiation as an independent risk factor for AIDS or death after HAART among HIV-infected men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:1030–8.

Desquilbet L, Margolick JB, Fried LP, Phair JP, Jamieson BD, Holloway M, et al. Relationship between a frailty-related phenotype and progressive deterioration of the immune system in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:299–306.

Onen NF, Agbebi A, Shacham E, Stamm KE, Onen AR, Overton ET. Frailty among HIV-infected persons in an urban outpatient care setting. J Infect. 2009;59:346–52.

Terzian AS, Holman S, Nathwani N, Robison E, Weber K, Young M, et al. Factors associated with preclinical disability and frailty among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in the era of cART. J Womens Health. 2009;18:1965–74.

Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Jankowski CM, Duong S, Mawhinney S, Kohrt WM, et al. Risk Factors for Falls in HIV-Infected Persons. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:484–9.

Holroyd-Leduc JM, Reddy M. Evidence-based geriatric medicine : a practical clinical guide. Chichester: Blackwell Pub; 2012.

Gill TM. Assessment of function and disability in longitudinal studies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58 Suppl 2:S308–12.

Bierman AS. Functional status: the six vital sign. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:785–6.

High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB, Cohen MH, Currier J, Deeks SG, et al. HIV and aging: state of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. J Acquir Immunodef Syndr. 2012;60 Suppl 1:S1–18. A high yield summary of priority areas in HIV and Aging as identified by leaders and funding agencies.

High KP, Bradley S, Loeb M, Palmer R, Quagliarello V, Yoshikawa T. A new paradigm for clinical investigation of infectious syndromes in older adults: assessment of functional status as a risk factor and outcome measure. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:114–22.

Justice AC. HIV and aging: time for a new paradigm. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2010;7:69–76.

Nagi SZ. A Study in the Evaluation of Disability and Rehabilitation Potential: Concepts, Methods, and Procedures. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1964;54:1568–79.

Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1–14.

Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–61.

Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, Du Q, Sarkisian CA. Disability and Decline in Physical Function Associated with Hospital Use at End of Life. J Gen Intern Med 2012

Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Naydeck BL, Boudreau RM, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt MC, et al. Association of long-distance corridor walk performance with mortality, cardiovascular disease, mobility limitation, and disability. JAMA. 2006;295:2018–26.

Rolland Y, Lauwers-Cances V, Cesari M, Vellas B, Pahor M, Grandjean H. Physical performance measures as predictors of mortality in a cohort of community-dwelling older French women. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21:113–22.

Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, Rosano C, Faulkner K, Inzitari M, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305:50–8. This landmark study demonstrates the remarkable ability of a simple measure of gait speed to predict mortality.

Vestergaard S, Patel KV, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM. Characteristics of 400-meter walk test performance and subsequent mortality in older adults. Rejuvenation Res. 2009;12:177–84.

De Buyser SL, Petrovic M, Taes YE, Toye KR, Kaufman JM, Goemaere S. Physical function measurements predict mortality in ambulatory older men. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:379–86.

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:255–63.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86.

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of Adl: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9.

Jette AM. Toward a common language of disablement. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1165–8.

In: The Future of Disability in America. Edited by Field MJ, Jette AM. Washington (DC); 2007.

Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Rehm J, Kennedy C, Epping-Jordan J, et al. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:815–23.

Garin O, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Almansa J, Nieto M, Chatterji S, Vilagut G, et al. Validation of the "World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, WHODAS-2" in patients with chronic diseases. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:51.

Patrick DL, Erickson P. Health status and health policy : quality of life in health care evaluation and resource allocation. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993.

Sherman SE, Reuben D. Measures of functional status in community-dwelling elders. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:817–23.

Cress ME, Schechtman KB, Mulrow CD, Fiatarone MA, Gerety MB, Buchner DM. Relationship between physical performance and self-perceived physical function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:93–101.

Wittink H, Rogers W, Sukiennik A, Carr DB. Physical functioning: self-report and performance measures are related but distinct. Spine. 2003;28:2407–13.

Kempen GI, Steverink N, Ormel J, Deeg DJ. The assessment of ADL among frail elderly in an interview survey: self-report versus performance-based tests and determinants of discrepancies. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1996;51:P254–60.

Oursler KK, Katzel LI, Smith BA, Scott WB, Russ DW, Sorkin JD. Prediction of cardiorespiratory fitness in older men infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: clinical factors and value of the six-minute walk distance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2055–61.

Longenberger A, Lim JY, Brown TT, Abraham A, Palella FJ, Effros RB, et al. Low physical function as a risk factor for incident diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance. Futur Virol. 2011;6:439–49.

Longenberger A, Lim JY, Orchard T, Brooks MM, Brach J, Mertz K, et al. Self-reported low physical function is associated with diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance in HIV-positive and HIV-negative men. Futur HIV Ther. 2008;2:539–49.

Oursler KK, Goulet JL, Leaf DA, Akingicil A, Katzel LI, Justice A, et al. Association of comorbidity with physical disability in older HIV-infected adults. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:782–91.

Rodriguez-Penney AT, Iudicello JE, Riggs PK, Doyle K, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, et al. Co-morbidities in persons infected with HIV: increased burden with older age and negative effects on health-related quality of life. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27:5–16.

Stanton DL, Wu AW, Moore RD, Rucker SC, Piazza MP, Abrams JE, et al. Functional status of persons with HIV infection in an ambulatory setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:1050–6.

Rusch M, Nixon S, Schilder A, Braitstein P, Chan K, Hogg RS. Impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions: prevalence and associations among persons living with HIV/AIDS in British Columbia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:46.

Harding R, Clucas C, Lampe FC, Date HL, Fisher M, Johnson M, et al. What factors are associated with patient self-reported health status among HIV outpatients? A multi-centre UK study of biomedical and psychosocial factors. AIDS Care. 2012;24:963–71.

Morgan EE, Iudicello JE, Weber E, Duarte NA, Riggs PK, Delano-Wood L, et al. Synergistic effects of HIV infection and older age on daily functioning. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:341–8.

Merlin JS, Westfall AO, Chamot E, Overton ET, Willig JH, Ritchie C, et al. Pain is Independently Associated with Impaired Physical Function in HIV-Infected Patients. Pain Med. 2013;14:1985–93.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56.

Fried LP, Xue QL, Cappola AR, Ferrucci L, Chaves P, Varadhan R, et al. Nonlinear multisystem physiological dysregulation associated with frailty in older women: implications for etiology and treatment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1049–57.

Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, Walston J, Guralnik JM, Chaves P, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women's health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:262–6.

Conroy S. Defining frailty–the Holy Grail of geriatric medicine. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:389.

Lang PO, Michel JP, Zekry D. Frailty syndrome: a transitional state in a dynamic process. Gerontology. 2009;55:539–49.

Blaum CS, Xue QL, Tian J, Semba RD, Fried LP, Walston J. Is hyperglycemia associated with frailty status in older women? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:840–7.

Drey M, Pfeifer K, Sieber CC, Bauer JM. The Fried frailty criteria as inclusion criteria for a randomized controlled trial: personal experience and literature review. Gerontology. 2011;57:11–8.

Avila-Funes JA, Amieva H, Barberger-Gateau P, Le Goff M, Raoux N, Ritchie K, et al. Cognitive impairment improves the predictive validity of the phenotype of frailty for adverse health outcomes: the three-city study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:453–61.

Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. The Tilburg Frailty Indicator: psychometric properties. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11:344–55.

Schuurmans H, Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Frieswijk N, Slaets JP. Old or frail: what tells us more? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:M962–5.

Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing. 2006;35:526–9.

Morley JE, Haren MT, Rolland Y, Kim MJ. Frailty. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90:837–47.

Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mitnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elderly people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:738–43.

Jones D, Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Evaluation of a frailty index based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment in a population based study of elderly Canadians. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:465–71.

Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:24.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–62.

Pialoux T, Goyard J, Lesourd B. Screening tools for frailty in primary health care: a systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12:189–97.

Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1537–51.

Avila-Funes JA, Amieva H. Frailty: an overused term among the elderly… even in gastroenterology. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009,43:199; author reply 199.

Margolick JB, Chopra RK. Relationship between the immune system and frailty: pathogenesis of immune deficiency in HIV infection and aging. Aging (Milano). 1992;4:255–7.

Althoff KN, Jacobson LP, Cranston RD, Detels R, Phair JP, Li X, et al. Age, Comorbidities, and AIDS Predict a Frailty Phenotype in Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013. doi:10.1093/gerona/glt148. Using the frailty-related phenotype in the MACS Cohort, these authors provide the first data on the stability of the frail state among HIV-infected men and clinical risk factors associated with transition in or out of the frail state.

Piggott DA, Muzaale AD, Mehta SH, Brown TT, Patel KV, Leng SX, et al. Frailty, HIV infection, and mortality in an aging cohort of injection drug users. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54910. This study in a nicely matched cohort of HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected intravenous drug users demonstrates the synergistic effect of both frailty and HIV in predicting mortality.

Onen NF, Patel P, Baker J, Conley L, Brooks JT, Bush T, et al. Frailty and pre-frailty in a contemporary cohort of HIV-infected adults. The Journal of Frailty & Aging 2013

Rees HC, Ianas V, McCracken P, Smith S, Georgescu A, Zangeneh T, et al. Measuring frailty in HIV-infected individuals. Identification of frail patients is the first step to amelioration and reversal of frailty. J Vis Exp 2013.

Sandkovsky U, Robertson KR, Meza JL, High RR, Bonasera SJ, Fisher CM, et al. Pilot study of younger and older HIV-infected adults using traditional and novel functional assessments. HIV Clin Trials. 2013;14:165–74.

Pathai S, Gilbert C, Weiss HA, Cook C, Wood R, Bekker LG, et al. Frailty in HIV-infected adults in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:43–51.

Morley JE, Perry HM, Miller DK. Editorial: Something About Frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M698–704.

Morley JE. Diabetes, sarcopenia, and frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2008;24:455–69.

Sayers SP, Guralnik JM, Newman AB, Brach JS, Fielding RA. Concordance and discordance between two measures of lower extremity function: 400 meter self-paced walk and SPPB. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2006;18:100–6.

Vasunilashorn S, Coppin AK, Patel KV, Lauretani F, Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, et al. Use of the Short Physical Performance Battery Score to predict loss of ability to walk 400 meters: analysis from the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:223–9.

Cesari M, Onder G, Zamboni V, Manini T, Shorr RI, Russo A, et al. Physical function and self-rated health status as predictors of mortality: results from longitudinal analysis in the ilSIRENTE study. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:34.

Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Skanderson M, Chang CC, Gibert CL, Goetz MB, et al. Towards a combined prognostic index for survival in HIV infection: the role of 'non-HIV' biomarkers. HIV Med. 2010;11:143–51.

Sourial N, Bergman H, Karunananthan S, Wolfson C, Payette H, Gutierrez-Robledo LM, et al. Implementing frailty into clinical practice: a cautionary tale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:1505–11.

Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Nevitt MC, Kritchevsky SB, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, et al. Measuring higher level physical function in well-functioning older adults: expanding familiar approaches in the Health ABC study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M644–9.

De Lorenzo A, Meirelles V, Vilela F, Souza FC. Use of the exercise treadmill test for the assessment of cardiac risk markers in adults infected with HIV. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2013;12:110–6.

Mbada CE, Onayemi O, Ogunmoyole Y, Johnson OE, Akosile CO. Health-related quality of life and physical functioning in people living with HIV/AIDS: a case-control design. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:106.

Mapstone M, Hilton TN, Yang H, Guido JJ, Luque AE, Hall WJ, et al. Poor Aerobic Fitness May Contribute to Cognitive Decline in HIV-infected Older Adults. Aging Dis. 2013;4:311–9.

Campo M, Oursler KK, Huang L, Goetz MB, Rimland D, Hoo GS, et al. Association of Chronic Cough and Pulmonary Function With 6-Minute Walk Test Performance in HIV Infection. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:557–63.

Grinspoon S, Corcoran C, Rosenthal D, Stanley T, Parlman K, Costello M, et al. Quantitative assessment of cross-sectional muscle area, functional status, and muscle strength in men with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome wasting syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:201–6.

Holguin A, Banda M, Willen EJ, Malama C, Chiyenu KO, Mudenda VC, et al. HIV-1 effects on neuropsychological performance in a resource-limited country, Zambia. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1895–901.

Robertson KR, Parsons TD, Sidtis JJ, Hanlon Inman T, Robertson WT, Hall CD, et al. Timed Gait test: normative data for the assessment of the AIDS dementia complex. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2006;28:1053–64.

Robertson K, Jiang H, Kumwenda J, Supparatpinyo K, Evans S, Campbell TB, et al. Improved neuropsychological and neurological functioning across three antiretroviral regimens in diverse resource-limited settings: AIDS Clinical Trials Group study a5199, the International Neurological Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:868–76.

Crawford KW, Li X, Xu X, Abraham AG, Dobs AS, Margolick JB, et al. Lipodystrophy and inflammation predict later grip strength in HIV-infected men: the MACS Body Composition substudy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29:1138–45.

Negin J, Martiniuk A, Cumming RG, Naidoo N, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Madurai L, et al. Prevalence of HIV and chronic comorbidities among older adults. AIDS. 2012;26 Suppl 1:S55–63.

Souza PM, Jacob-Filho W, Santarem JM, Zomignan AA, Burattini MN. Effect of progressive resistance exercise on strength evolution of elderly patients living with HIV compared to healthy controls. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:261–6.

Raso V, Shephard RJ. do Rosario Casseb JS, da Silva Duarte AJ, D'Andrea Greve JM. Handgrip force offers a measure of physical function in individuals living with HIV/AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:e30–2.

Baranoski AS, Harris A, Michaels D, Miciek R, Storer T, Sebastiani P, et al. Relationship Between Poor Physical Function, Inflammatory Markers, and Comorbidities in HIV-Infected Women on Antiretroviral Therapy. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23:69–76.

Richert L, Brault M, Mercie P, Dauchy FA, Bruyand M, Greib C, et al. Decline in locomotor functions over time in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2014. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000246. Although the follow-up time was short, this study provides some of the first rates of change in several measures of objective physical function, essential data needed to power future interventional studies to prevent physical function decline.

Sullivan EV, Rosenbloom MJ, Rohlfing T, Kemper CA, Deresinski S, Pfefferbaum A. Pontocerebellar contribution to postural instability and psychomotor slowing in HIV infection without dementia. Brain Imaging Behav. 2011;5:12–24.

Wasserman P, Segal-Maurer S, Rubin DS. High Prevalence of Low Skeletal Muscle Mass Associated with Male Gender in Midlife and Older HIV-Infected Persons Despite CD4 Cell Reconstitution and Viral Suppression. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2013. doi:10.1177/2325957413495919.

Bauer LO, Wu Z, Wolfson LI. An obese body mass increases the adverse effects of HIV/AIDS on balance and gait. Phys Ther. 2011;91:1063–71.

Bauer LO, Ceballos NA, Shanley JD, Wolfson LI. Sensorimotor dysfunction in HIV/AIDS: effects of antiretroviral treatment and comorbid psychiatric disorders. AIDS. 2005;19:495–502.

Fama R, Eisen JC, Rosenbloom MJ, Sassoon SA, Kemper CA, Deresinski S, et al. Upper and lower limb motor impairments in alcoholism, HIV infection, and their comorbidity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1038–44.

Scott WB, Oursler KK, Katzel LI, Ryan AS, Russ DW. Central activation, muscle performance, and physical function in men infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:374–83.

Shah K, Hilton TN, Myers L, Pinto JF, Luque AE, Hall WJ. A new frailty syndrome: central obesity and frailty in older adults with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:545–9.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R03AG040594-01] and the Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence in Geriatric Medicine. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Jennifer A. Schrack and Catherine M. Jankowski declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Kristine M. Erlandson reports grants from Hartford Foundation, grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study.

Todd T. Brown reports personal fees from Merck, personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, personal fees from Abbvie, personal fees from EMD-Serono, personal fees from Gilead, outside the submitted work.

Thomas B. Campbell reports grants from US NIH, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Gilead Sciences, outside the submitted work; has served as a consultant to Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Abbvie, EMD-Serono, and Gilead.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Erlandson, K.M., Schrack, J.A., Jankowski, C.M. et al. Functional Impairment, Disability, and Frailty in Adults Aging with HIV-Infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 11, 279–290 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-014-0215-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-014-0215-y