Abstract

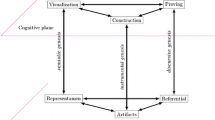

Mathematical working space (MWS) is a model that is used in research in mathematics education, particularly in the field of geometry. Some MWS elements are independent of the field while other elements must be adapted to the field in question. In this paper, we develop the MWS model for the field of analysis with an identification of paradigms. We show the advantages of this MWS model, which takes into account the epistemological and cognitive aspects of mathematical work, and more specifically the semiotic, instrumental and discursive geneses, by making them function as one system. By using examples and data from three countries, we illustrate how this model can be used to perform a priori analyses and analyses of class situations and individual student work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This paper focuses only on one-dimensional real analysis, which is taught at the upper secondary levels and in the first years of university (including teacher training programs).

We do not use the term calculus, which is subject to different interpretations.

The letter ε is representative of a type of work or thought that is used even in non-formal mathematicians’ language to mention a negligible quantity, but work in RA is not restricted to this kind of work with ε (see Sect. 3). RA paradigm brings also a topological idea of analysis in the case of R equipped with the usual topology.

a√3/2 is the height CD and a 2√3/8 is half the total area of triangle ABC.

Local reasoning, which could lead to a switch to the RA paradigm, is then possible but not necessary. Through semiotic genesis, the curve through R may be shown to be a function z→r(z). At a/2, in RA r can be said to be a function of z locally, while in CA it is probable that only the relevant formula r(z) dominating the calculations may be identified (i.e., the one that takes the value 0 at a/2).

There is no a priori separation of the CA and RA paradigms. Both paradigms can coexist in the mathematical activity.

References

Arcavi, A., & Hadas, N. (2000). Computer mediated learning: An example of an approach. International Journal of Computers for Mathematical Learning, 5, 25–45.

Beke, E. (1914). Les résultats obtenus dans l’introduction du calcul différentiel et intégral dans les classes supérieures des établissements secondaires, L’Enseignement Mathématiques, Vol. 16. Genève.

Bergé, A. (2008). The completeness property of the set of real numbers in the transition from calculus to analysis. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 67, 217–235.

Biza, I., & Zachariades, T. (2010). First year mathematics undergraduates’ settled images of tangent line.Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 29, 218–229.

Di Rico, E., Lamela, C., Luna, P., & Sessa, C. (2015). Figuras dinámicas y funciones: representaciones vinculadas en la pantalla de Geogebra. In Proceedings of CIAEM XIV, 5–7 June 2015, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, México.

Dubinsky, E., Weller, K., Michael, A. Mc, Donald, M. A., & Brown, A. (2005). Some historical issues and paradoxes regarding the concept of infinity: an APOS-based analysis: part 2. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 60, 253–266.

Ely, R. (2010). Nonstandard student conceptions about infinitesimals. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 41(2), 117–146.

Hodgson, B.R. (1994). Le calcul infinitésimal, In D.F. Robitaille, D.H. Wheeler et C. Kieran, dir (Eds.), Choix de conférence du 7e Congrès international sur l’enseignement des mathématiques (ICME-7), Presses de l’Université Laval (pp. 157–170).

Houdement, C., & Kuzniak, A. (2006). Paradigmes géométriques et enseignement de la géométrie. Annales de Didactique et de Sciences Cognitives, 11, 175–193.

Kuzniak, A. (2004). Paradigmes et espaces de travail géométriques. (Note pour l’habilitation à diriger des recherches). Paris: Institut de Recherche sur l’Enseignement des Mathématiques Paris VII.

Kuzniak, A. (2006). Paradigmes et espaces de travail géométriques. Éléments d’un cadre théorique pour l’enseignement et la formation des enseignants en géométrie. Canadian Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 6(2), 167–188.

Kuzniak, A. (2011). L’espace de Travail Mathématique et ses genèses. Annales de didactique et de sciences cognitives, 16, 9–24.

Kuzniak, A., & Richard, P. R. (2014). Spaces for mathematical work. Viewpoints and perspectives. RELIME, 17(4-I), 17–28.

Maschietto, M. (2002). L’enseignement de l’analyse au lycée: les débuts du jeu global/local dans l’environnement de calculatrices. Thèse doctorale, Université Paris VII.

Mena-Lorca, A., Mena-Lorca, J., Montoya-Delgadillo, E., Morales, A., & Parraguez, M. (2015). El obstáculo epistemológico del infinito actual: persistencia, resistencia y categorías de análisis. Revista Latinoamericana de Investigación en Matemática Educativa, 18(3), 329–358.

Montoya Delgadillo, E. (2014). El proceso de prueba en el espacio de trabajo geométrico: profesores en formación inicial. Revista Enseñanza de las Ciencias., 32(3), 227–247.

Montoya Delgadillo, E., & Vivier, L. (2014). Les changements de domaine dans le cadre des Espaces de Travail Mathématique. Annales de Didactique et de Sciences Cognitives, 19, 73–101.

Montoya Delgadillo, E., & Vivier, L. (2015). ETM de la noción de tangente en un ámbito gráfico—Cambios de dominios y de puntos de vista, In Proceedings of CIAEM XIV, 5–7 June 2015, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, México.

Oktaç, A., & Vivier, L. (2016). Conversion, change, transition… In B. R. Hodgson, A. Kuzniak, J. -B. Lagrange (Eds.), The Didactics of Mathematics: Approaches and Issues. A Hommage to Michèle Artigue, chapter 4, (pp. 87–122). Switzerland: Springer.

Páez Murillo, R. E., & Vivier, L. (2013). Evolution of teachers’ conceptions of tangent line. Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 32, 209–229.

Rittaud, B., & Vivier, L. (2014). Different praxeologies for rational numbers in decimal system—the \(0,\bar{9}\) case, In Proceedings of Cerme 8, Antalya.

Robert, A., & Vivier, L. (2013). Analyser des vidéos sur les pratiques des enseignants du second degré en mathématiques : des utilisations contrastées en recherche en didactique et en formation de formateurs. Éducation et Didactique, 7(2), 115–144.

Robinson, A. (1966). Non-standard Analysis, North Holland.

Sierpinska, A. (1985). Obstacles épistémologiques relatifs à la notion de limite. Recherche en Didactique des Mathématiques, 6(1), 5–67.

Tall, D. O. (1980). Intuitive infinitesimals in the calculus, In Poster presented at the Fourth International Congress on Mathematical Education, Berkeley.

Tall, D. O., & Schwarzenberger, R. L. E. (1978). Conflicts in the learning of real numbers and limits. Mathematics Teaching, 82, 44–49.

Vandebrouck, F. (2011a). Perspectives et domaines de travail pour l’étude des fonctions. Annales de Didactique et de Sciences Cognitives, 16, 149–185.

Vandebrouck F. (2011b). Des technologies pour l’enseignement et l’apprentissage des fonctions du lycée à l’université : activités des élèves et pratiques des enseignants. Note d’Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches. Université Paris Diderot.

Vincent, B., LaRue, R., Sealey, V., & Engelke, N. (2015). Calculus students’ early concept images of tangent lines. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 46(5), 641–657.

Weller, K., Arnon, I., & Dubinsky, E. (2009). Preservice teachers’ understanding of the relation between a fraction or integer and its decimal expansion. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 9(1), 5–28.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the ECOS-Sud C13H03 project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11858-016-0793-9.

Appendix 1: Curves

Appendix 1: Curves

Instructions: For each of the following curves, draw a tangent line at the point indicated when such a tangent exists, or provide an explanation if it does not.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Delgadillo, E.M., Vivier, L. Mathematical working space and paradigms as an analysis tool for the teaching and learning of analysis. ZDM Mathematics Education 48, 739–754 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-016-0777-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-016-0777-9