Abstract

The ability to predict stock returns from financial ratios is a long-standing but still controversial topic. There is ongoing debate about the empirical evidence as well as about appropriate theoretical explanations. We provide evidence from a simulated economy that local, social interaction among agents is remarkably successful in matching several established empirical facts. We find significant return predictability at various forecast horizons, absence of dividend growth predictability, high persistence in dividend yields, and absence of significant return autocorrelations. Our results suggest that social dynamics are a simple, intuitively appealing and successful way to explain predictability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Collard et al. (2006) stress the role of persistence in explaining predictability.

Cecchetti et al. (2000) address the well-known equity premium puzzle, while Whitelaw (2000) shows that regime-switching models can explain the non-linear relationship between expected returns and volatility. Empirically, Lettau and Van Nieuwerburgh (2008) argue that taking account of regime-switches substantially strengthens the evidence for return predictability.

Predictability can be traced back to the persistence in the updated estimates. However, Timmermann (1993) considers the case where a representative agent has incomplete information with respect to constant drift and diffusion parameters. In such a set-up, the predictability effect fades out quickly, since a constant can be estimated with high accuracy after only few observations.

In the following, we will use the terms ‘social dynamics’ and ‘local interaction’ synonymously.

“Investing in speculative assets is a social activity. Investors spend a substantial part of their leisure time discussing investments, reading about investments, or gossiping about others’ successes or failures in investing. It is thus plausible that investors’ behavior (and hence prices of speculative assets) would be influenced by social movements.” Shiller (1984), p. 457.

In this sense, Kirman (1992) argues: “The sum of the behavior of simple economically plausible individuals may generate complicated dynamics, whereas constructing one individual whose behavior has these dynamics may lead to that individual having very unnatural characteristics.” (Kirman 1992, p. 118). In Kirman (1993), he puts forward a model that replicates the dynamics of opinions in a social context and explains apparent abrupt changes in aggregate behavior.

In general, the agents opportunity set is frequently assumed to additionally contain a riskless asset which is in zero net supply. However, note that in this endowment economy, equilibrium requires that aggregate consumption equals aggregate dividends, so that all agents only hold the risky asset, and the rate of return on the riskless asset is only to be interpreted as the economy’s shadow risk-free interest rate.

The interpretation can be justified by results in Carroll (2003), who shows that unlike households, professional forecasters are able to form close to rational expectations.

In more formal terms, we may define the neighborhood of agent i as \( \mathbb{N}_{i} = \{ j;(i - 1){\text{mod}}\,N \le {\text{j}} \le ({\text{i + 1}}){\text{mod}}\,N\} \), where the modulo operator makes sure that the neighborhood of agent N includes agent 1, since 501 mod 500 = 1. Note further that the neighborhood definition does not imply that agent i is her own neighbor, which would violate the condition of irreflexivity, but that the neighborhood \({{\mathbb{N}}_i}\) characterizes the group of agents to which agent i belongs. Including the element of the network in his own neighborhood is common in the construction of cellular automata.

An extension to finitely many different states would be straightforward.

Considering the impact of the mood of investors on asset returns is by no means an exotic issue, but has already been discussed in the behavioral finance literature. Saunders (1993) and Hirshleifer and Shumway (2003) for example find evidence that the weather has a significant influence on stock returns, the channel being the mood of investors.

Note that we do not consider the influence of market prices. There are basically two reasons: On the one hand, it is far from clear what agents can infer from market prices in such an environment, and on the other hand, in the pure exchange economy, prices have no speculative role.

They are identical in each time step except for the initial random distribution of states in t 0. Initial states of agents are iid from a uniform distribution.

This is also the reason why we ourselves were cautious in writing above that agents try to maximize their life-time utility.

The necessary condition that the infinite sum in (8) converges is (2 μ(s) − γ σ 2 D ) > 0, which will be always satisfied by the numerical simulations.

Note that the functional form of the value function V (s) t+1 (i.e. utility of a share of current dividend times a constant) is also obtained if the optimization horizon is extended to arbitrary finite time horizons. See Hillebrand and Wenzelburger (2007).

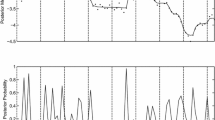

By taking this example to the extreme, we would obtain a dp t series which is piece-wise constant at two levels, such as e.g. in Cecchetti et al. (1990).

It is common to regress on the log dividend-price ratio dp t = − pd t .

We set the initial growth rate to μ 0 = μ h , the initial estimate \(\hat{\mu}_0=0.5\), and the initial dividend yield to dp 0 = −3. We drop initial values from the final sample.

See also Cochrane (2005), p. 455 et seq. for a discussion.

Note that the standard OLS coefficient would be 0.0363 with a standard error of 0.0147, implying a t-stat of 2.679, which confirms the upward bias in both the coefficient and t values. Note further that the Newey-West corrected standard errors are 0.0133, implying an even larger t-statistic of 2.972.

\(\bar{pd}=3.359\) implies a price-dividend ratio of 28.76 or a dividend yield of 3.47 %.

See Cochrane (2008), p.1540 for a more detailed discussion.

Cochrane (2008) calls this finding the “dog that did not bark”-effect, following the famous Sherlock Holmes case.

This finding is consistent with the results in Cecchetti et al. (1990).

Indeed, from unreported results, we find that the partial autocorrelation function at higher lags goes down to zero.

References

Amihud Y, Hurvich CM (2004) Predictive regressions: a reduced-bias estimation method. J Financ Quant Anal 39(4):813–841

Ang A, Bekaert G (2007) Stock return predictability: is it there? Rev Financ Stud 20(3):651–707

Ang A, Liu J (2007) Risk, return, and dividends. J Financ Econ 85(1):1–38

Baker M, Wurgler J (2007) Investor sentiment in the stock market. J Econ Perspect 21(2):129–151

Bansal R, Yaron A (2004) Risks for the long run: a potential resolution of asset pricing puzzles. J Financ 59(4):1481–1509

Bikhchandani S, Hirshleifer D, Welch I (1992) A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural change as informational cascades. J Polit Econ 100(5):992–1026

Boudoukh J, Richardson M, Whitelaw RF (2008) The myth of long-horizon preditability. Rev Financ Stud 21(4):2008

Brennan M, Xia Y (2001) Stock price volatility and equity premium. J Monet Econ 47:249–283

Brown JR, Ivkovic Z, Smith PA, Weisbenner S (2008) Neighbors matter: causal community effects and stock market participation. J Financ 63(3):1509–1531

Calvet LE, Fisher AJ (2007) Multifrequency news and stock returns. J Financ Econ 86:178–212

Campbell JY, Cochrane JH (1999) By force of habit: a consumption-based explanation of aggregate stock market behavior. J Polit Econ 107(2):205–251

Campbell JY, Lo AW, MacKinlay AG (1997) The econometrics of financial markets. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Campbell JY, Shiller RJ (1989) The dividend-price ratio and expectations of future dividends and discount factors. Rev Financ Stud 1(3):195–228

Carroll CD (2003) Macroeconomic expectations of households and professional forecasters. Quart J Econ 118(1):269–298

Cecchetti SG, Lam P-S, Mark NC (1990) Mean reversion in equilibrium asset prices. Am Econ Rev 80(3):398–418

Cecchetti SG, Lam P-S, Mark NC (2000) Asset pricing with distorted beliefs: are equity returns too good to be true? Am Econ Rev 90(4):787–805

Cochrane JH (1992) Explaining the variance of price-dividend ratios. Rev Financ Stud 5(2):243–280

Cochrane JH (2005) Asset pricing, 2nd edn. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Cochrane JH (2008) The dog that did not bark: a defense of return predictability. Rev Financ Stud 21(4):1533–1575

Collard F, Fève P, Ghattassi I (2006) Predictability and habit persistence. J Econ Dyn Control 30:2217–2260

Cont R, Bouchaud J-P (2000) Herd behavior and aggregate fluctuations in financial markets. Macroecon Dyn 4(2):170–196

Dangl T, Halling M (2012) Predictive regressions with time-varying coefficients. J Financ Econ 106(1):157–181

Fama EF, French KR (1989) Business conditions and expected returns on stocks and bonds. J Financ Econ 25(1):23–49

Farmer J, Joshi S (2002) The price dynamics of common trading strategies. J Econ Behav Organ 49(2):149–171

Ferson WE, Harvey CR (1993) The risk and preditability of international equity returns. Rev Financ Stud 6(3):527–566

Gali J (1994) Keeping up with the joneses: Consumption externalities, portfolio choice, and asset prices. J Money Credit Bank 26(1):1–8

Goyal A, Welch I (2003) Predicting the equity premium with dividend ratios. Manag Sci 49(5):639–654

Goyal A, Welch I (2008) A comprehensive look at the empirical performance of equity premium prediction. Rev Financ Stud 21(4):1455–1508

Goyal S (2007) Connections, an introduction to the economics of networks. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Grinblatt M, Keloharju M, Ikäheimo S (2008) Social influence and consumption: evidence from the automobile purchases of neighbours. Rev Econ Stat 90(4):735–753

Hamilton JD (1989) A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica 57(2):357–384

Hamilton JD (2008) Regime-switching models. In Durlauf SN, Blume LE (eds) The new palgrave dictionary of economics. Palgrave Macmillan, UK

Hillebrand M, Wenzelburger J (2007) Multi-period consumption and investment decisions under uncertainty revisited. Working paper, Bielefeld University

Hirshleifer D, Shumway T (2003) Good day sunshine: stock returns and the weather. J Financ 58(3):1009–1032

Hong H, Kubik JD, Stein JC (2004) Social interaction and stock-market participation. J Financ 59(1):137–163

Kaustia M, Knüpfer S (2012) Peer performance and stock market entry. J Financ Econ 104(2):321–338

Kirman A (1992) Whom or what does the representative individual represent? J Econ Perspect 6(2):117–136

Kirman A (1993) Ants, rationality, and recruitment. Quart J Econ 108(1):137–156

Koijen RS, Van Binsbergen JH (2010) Predictive regressions: a present-value approach. J Financ 65(4):1439–1471

Koijen RS, Van Nieuwerburgh S (2009) Financial economics, return predictability and market efficiency. In Meyers RA (ed) Encyclopedia of complexity and systems science. Springer, Berlin

Lettau M, Ludvigson S (2001) Consumption, aggregate wealth, and expected stock returns. J Financ 56(3):815–849

Lettau M, Van Nieuwerburgh S (2008) Reconciling the return predictability evidence. Rev Financ Stud 21(4):1607–1652

Lewellen J (2004) Predicting returns with financial ratios. J Financ Econ 74:209–235

Lucas REJ (1978) Asset prices in an exchange economy. Econometrica 46(6):1429–1445

Lux T (2009) Rational forecasts or social opinion dynamics? Identification of interaction effects in a business climate survey. J Econ Behav Organ 72:638–655

Lux T, Marchesi M (1999) Scaling and criticality in a stochastic multi-agent model of a financial market. Nature 397:498–500

Mehra R, Prescott EC (1985) The equity premium: a puzzle. J Monet Econ 15:145–161

Mehra R, Prescott EC (2003) The equity premium in retrospect. In Constantinides GM, Harris M, Stulz RM (eds) Handbook of the economics of finance: financial markets and asset pricing, volume 1B of handbooks in economics. Amsterdam, North-Holland

Menzly L, Santos T, Veronesi P (2004) Understanding predictability. J Polit Econ 112(1):1–47

Morris S (2000) Contagion. Rev Econ Stud 67:57–78

Orlean A (1995) Bayesian interactions and collective dynamics of opinion: Herd behavior and mimetic contagion. J Econ Behav Organ 28:257–274

Ozoguz A (2009) Good times or bad times? Investors’ uncertainty and stock returns. Rev Financ Stud 22(11):4377–4422

Paye BS, Timmermann A (2006) Instability of return prediction models. J Empir Financ 13:274–315

Saunders EMJ (1993) Stock prices and wall street weather. Am Econ Rev 83:1337–1345

Shiller RJ (1984) Stock prices and social dynamics. Brookings Papers Econ Activity 2:457–498

Stambaugh RF (1999) Predictive regressions. J Financ Econ 54:375–421

Summers LH (1986) Does the stock market rationally reflect fundamental values? J Financ 41(3):591–601

Timmermann A (1993) How learning in financial markets generates excess volatility and predictability in stock prices. Quart J Econ 108(4):1135–1145

Veronesi P (2000) How does information quality affect stock returns? J Financ LV(2):807–837

Whitelaw RF (2000) Stock market risk and return: an equilibrium approach. Rev Financ Stud 13(3):521–547

Wolfram S (2002) A new kind of science. Wolfram Media, Champaign

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthias Bank, Christian Flor, Arie Gozluklu, Jörn van Halteren, Stefan Hirth, Wolfgang Kürsten (the editor), Maik Schmeling, Lorne Switzer, Martin Wallmeier, an anonymous referee that provided a very detailed and helpful report, and seminar participants at the German Finance Association Annual Meeting 2010 Hamburg, the European Financial Management Association Annual Meeting 2010 Aarhus, the Financial Management Association European Annual Meeting 2010 Hamburg, and the Financial Management Association Annual Meeting 2010 New York. As always, all remaining errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hule, R., Lawrenz, J. Return predictability and social dynamics. Rev Manag Sci 7, 159–189 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-013-0099-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-013-0099-z