Abstract

Long-term relationships with family forest owners willing to sell roundwood are important for the Nordic forest industry. Research has shown that customer loyalty is mediated by a sense of commitment to the service provider. At least two forms of commitment have been distinguished: affective commitment in the sense of liking the provider, and calculative commitment in the sense of being dependent on the provider. In Sweden, more than one-third of family forest owners are members of a forest owners’ association with the primary objective of supporting its members’ profitability. The associations buy one-third of the owners’ roundwood. This study examined the role of different forms of commitment in the process of becoming loyal timber suppliers, and the moderating role of membership. A questionnaire was sent to forest owners who notified the authorities of a final harvesting operation involving timber procurement by an organization. The results show that both forms of commitment significantly affected loyalty and the forms were correlated. Members of forest owners’ associations who sold their timber to the association expressed higher affective commitment and loyalty than other forest owners, indicating that a sense of member involvement is important for timber procurement by the associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2013, Sweden had around 329,400 private forest owners (often referred to as family forest owners) of 229,802 forest properties (Swedish Forest Agency 2014). They supply more than half of roundwood used by the forest industry (Swedish Forest Agency 2014). The industry faces increasing competition for the timber that is offered for sale because of the aging of forest owners, urbanization and a reduction in the dependency of forest owners on income from their forest land. Therefore the industry has an interest in building long-term relationships with its suppliers. At the same time, only a marginal percentage of forest owners now perform their own harvesting operations; today’s timber deals very often include the purchase of harvesting services from the timber procurer as well as potential subsequent silvicultural activities on the property. Therefore, private forest owners are both suppliers of timber as well as customers of harvesting and silvicultural services, and it is in the context of harvesting services customers that this study was conducted. According to Dwyer et al. (1987) and Morgan and Hunt (1994), successful long-term relationships between customers and service suppliers require relationship commitment and trust. Subsequent research on commitment by authors such as Fullerton (2003, 2005) and Gruen et al. (2000) showed that commitment includes various components that affect customer loyalty in different ways. Berghäll (2003) studied the commitment of Finnish forest owners to their timber procurement organizations and found two components: a calculative component and an emotional component.

In Sweden, 37% of forest owners are at present members of a forest owners’ association (Swedish Forest Agency 2014). These members own 55% of the productive forest land owned by private forest owners (Swedish Forest Agency 2014). Forest owners’ associations are co-operative organizations with the principal objective of promoting the economic interests of their members, by trading in members’ roundwood and other forest products or by processing the roundwood in member-owned industries, among other activities. Members invest in the organizations and receive a return on the profit when they supply them with roundwood. Members also elect representatives who are involved in the steering of the organizations. According to Stryjan (1994), members’ loyalty in delivering timber to these associations is the basis of the operations for this type of co-operative organization, as the associations’ objective is to assure good timber prices for their members. Loyalty also makes steering of such co-operatives possible. According to the Swedish law, co-operatives cannot force members to deal only with them; in other words, associations must earn their members’ loyalty. The annual reports of the Swedish forest owners’ associations for 2014 show that they procure approximately one-third of the annual timber harvested in Sweden.

According to Mattila et al. (2013), the present operations of the forestry service markets are not fully adapted to the structural changes among forest owners. Very few studies have evaluated forest owners’ opinions of the actual services offered and their effect on commitment and loyalty to the timber procurement organizations. Interest among forest owners in selling timber to the forest industry is expected to decrease because of continuing structural changes (Häyrinen et al. 2015). Therefore, from a sectoral perspective, it is interesting to understand the perspectives of forest owners regarding their commitment to the service providers and the effect of this commitment on their loyalty. This would provide insight into what forest owners value in their business relations. Because membership in a forest owners’ association implies both a financial investment and some sort of commitment to the co-operate values, it seems pertinent in such an investigation to include the moderating effect of membership on commitment and loyalty among forest owners who sell timber to their member organizations. This importance is further strengthened by the share of business being conducted with the associations.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Jacoby and Chestnut (1978) began the development of the modern concept of customer loyalty by concluding that using repeat purchase behaviour as the sole measure of loyalty was invalid, as a customer could be loyal to several brands at the same time or could buy the same brand out of habit. The few studies of the loyalty of forest owners to timber procurement organizations have basically been limited to customer retention (Kärhä and Oinas 1998; Lönnstedt 1997). Lönnstedt (1997) found that Swedish forest owners tended to repeat doing business with the same timber procurer without looking for other options unless the forest owner was dissatisfied with a previous timber deal.

Many definitions of loyalty have been proposed in the marketing literature since then. Gremler and Brown (1996, p. 173) defined loyalty to a service organization as “the degree to which a customer exhibits repeat purchasing behaviour from a service provider, possesses a positive attitudinal disposition toward the provider, and considers using only this provider when a need for this service arises”. Oliver (1999) developed a framework of sequential effects leading to behavioural loyalty which is shortly described here. Oliver (1999) argued that customers become loyal in a cognitive sense first when they prefer a certain brand to another. This preference is based upon beliefs about the brands and/or recent experiences and is based purely on satisfaction with attributes or performance levels. However this cognitive loyalty is of a shallow nature, and competitors can respond relatively easily with counter information or special offers. In the second phase the customer develops a liking for the brand because of cumulative satisfying experiences. These pleasurable experiences lead to a commitment to the brand, which for competitors becomes more difficult to counter with rational arguments. In the next phase, the customer develops a deep brand-specific commitment and is thus highly motivated to repurchase the products or service. He/she may also express congenial opinions about the brand to peers. However while intentions may be good, implementation is not guaranteed. Therefore, the last sequence to genuine loyalty is action or behavioural loyalty according to Oliver (1999).

Following Oliver’s framework, the essential start for the development of loyalty is therefore customer satisfaction. Being a very general, and therefore difficult to measure, concept, Oliver (2010) describes the concept as a judgement of the product/service provided and the way in which it could provide a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfilment. Very few studies have been conducted on customer satisfaction with timber harvesting services, and those that have been conducted have focused on the performance out in the field (Kärhä and Oinas 1998). For this study, customer satisfaction was measured using questions of the SERVQUAL questionnaire developed by Parasuraman et al. (1988), which gives a measure of the perceived quality of the relationship which was interpreted as a measure for satisfaction.

Oliver’s (1999) framework describes that the development from satisfaction to loyalty is mediated by commitment. This was also shown by a number of researchers (Morgan and Hunt 1994; Garbarino and Johnson 1999; Gruen et al. 2000; Fullerton 2003; Bansal et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2008). Commitment in a commercial relationship context has been defined by Moorman et al. (1992, p. 316) as “an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship”. According to the commitment-trust theory developed by Morgan and Hunt (1994), commitment is influenced by the costs of terminating the relationship, its benefits as well as the shared values. Costs of termination consist of the time and effort that the forest owner will need to invest in building up a relationship with another timber procurer. Relational benefits that the forest owners may be interested in are better terms in the deal (a better price for their timber, lower harvesting costs, “extras” that would normally be difficult to obtain in a first-time timber deal) or access to the professional advice. Morgan and Hunt (1994) describe shared values as the extent to which the partners have a common understanding about behaviour (what constitute “good” and “bad” forestry practices), business goals and policies that are important in the eyes of the partners.

Morgan and Hunt (1994) describe commitment as a unidimensional construct. It is however common to distinguish more dimensions of the commitment concept, as customers may wish to continue the relationship for different reasons and to different extents. Garbarino and Johnson (1999), Gruen et al. (2000), Gilliland and Bello (2002) and Fullerton (2003) identify “affective” commitment in the sense that customers develop an emotional attachment to the relationship with their business partner that is rooted in the shared values, as described by Morgan and Hunt (1994). Customers who are affectively committed to their partners enjoy doing business with them and trust them (Fullerton 2005). Timber deals in Sweden are predominantly discussed in the home environment of the forest owner. They often include several personal meetings and often touch upon the private life of the forest owners (such as the family situation or their ideas about the future of the property in the family). Shared values may therefore be a very important aspect in the timber deal’s discussion, and affective commitment may be an important mediator of loyalty for a forest owner. Fullerton (2005), Han et al. (2008) and Davis-Sramek et al. (2009) found a positive relationship between satisfaction and affective commitment. Gilliland and Bello (2002) found that goodwill actions taken by a business partner enhanced each party’s affective commitment to the relationship. The first hypothesis for this study was therefore formulated as follows:

H 1

Customer satisfaction will have a positive impact on affective commitment.

The second dimension of commitment often identified has its roots in the scarcity of alternatives and/or switching costs, or in the benefits that cannot easily be replaced by other partners [Morgan and Hunt’s (1999) relational benefits]. Gilliland and Bello (2002) use the term “calculative commitment” to emphasize that it is the result of an opportunistic behaviour (rather than passive behaviour) of the customer evaluating alternatives. Price and Arnould (1999), Han et al. (2008) and Davis-Sramek et al. (2009) found a positive relationship between satisfaction and calculative commitment which was mainly explained by the fact that increased satisfaction will make switching to another business partner less attractive. The following hypothesis was therefore formulated:

H 2

Customer satisfaction will have a positive impact on calculative commitment.

According to Morgan and Hunt (1994) and Price and Arnould (1999), advocacy (or the willingness to advocate for their business partner to peers) is besides loyalty, an important result of commitment. This was also mentioned as a step to loyalty in Oliver’s (1999) framework. Fullerton (2003) found that affective commitment had a positive impact on customers’ willingness to advocate for a service organization, so did Shukla et al. (2016). Persons that have an affective commitment to the organization want the organization to succeed and are therefore willing to act as a reference to this organization according to Fullerton (2005). Positive calculative experiences were found to have also a positive influence on the willingness to advocate according to Gruen et al. (2000) and Shukla et al. (2016). The following hypotheses were therefore formulated:

H 3

Affective commitment will have a positive impact on willingness to advocate.

H 4

Calculative commitment will have a positive impact on willingness to advocate.

According to Oliver (1999), the process of developing loyalty includes both rational arguments as well as the liking of the brand. It is therefore very likely that affective commitment and calculative commitment as operationalized in this study will be correlated. Davis-Sramek et al. (2009) argued that the benefits leading to calculative commitment may enhance the attachment to the business partner. Therefore our hypothesis is:

H 5

There is a positive interactive effect between affective commitment and calculative commitment on the willingness to advocate.

Garbarino and Johnson (1999), Gruen et al. (2000), Han et al. (2008), Fullerton (2003, 2005), Davis-Sramek et al. (2009) and Shukla et al. (2016) all found a positive relationship between affective commitment and loyalty, so therefore in this study a similar result is expected. Between calculative commitment and loyalty, positive relationships were found by Han et al. (2008), Fullerton (2005) and Keiningham et al. (2015). With similar arguments as for the intentions to advocate, we expect a positive relationship between calculative commitment and loyalty as well as a positive effect of the interactive effect between affective commitment and calculative commitment. The following hypotheses were therefore formulated:

H 6

Affective commitment will have a positive impact on loyalty.

H 7

Calculative commitment will have a positive impact on loyalty.

H 8

There is a positive interactive effect between affective commitment and calculative commitment on loyalty.

Gruen et al. (2000) found that commitment only partially mediated the development of loyalty. Customer satisfaction was also found to have a significant direct effect on loyalty, which Gruen et al. (2000, p. 44) explained by suggesting that customers are increasingly becoming short-term focused on the question “what have you done for me lately”. Fullerton (2005) and Davis-Sramek et al. (2009) did not find a direct effect of customer satisfaction on loyalty. As these two positions may have different practical implications for timber procurement organizations it was decided to include customer satisfaction in the models for both advocacy and loyalty with the following hypotheses:

H 9

Customer satisfaction has a direct positive impact on advocacy.

H 10

Customer satisfaction has a direct positive impact on loyalty.

Bhattacharya (1998), Gruen et al. (2000) and Vincent and Webster (2013) studied the effect of customers’ membership on loyalty to associations. Their results confirm that in membership organizations, loyalty is also mediated by commitment, in particular affective commitment. Forest owners’ associations are co-operative organizations build on the co-operative ideology, which is based on values such as self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equity, equality and solidarity (International Cooperative Alliance 2015). Becoming a member would (at least in theory) imply that members share this ideology and therefore positively affect their affective commitment. The proposed hypothesis therefore is:

H 11

Members who sell their timber to their forest owners’ association will have higher levels of affective commitment than other forest owners will.

Forest owner associations are guided by both ideological and economical principles. In joining the association, members invest capital in the association and thereby become owners (Kittredge 2003). The decision to invest can be regarded as an expression of calculative commitment, as members must be eager to obtain a good return on their investments (Österberg and Nilsson 2009) and want access to certain services and benefits offered by the organization. The organizations offer profit-sharing systems as well as high timber prices compared to competitors. Our hypothesis is therefore:

H 12

Members who sell their timber to their forest owners’ association will have higher levels of calculative commitment than other forest owners.

Forest owners’ associations have their roots in the Swedish popular movements (“folkrörelse” in Swedish) with the objective of changing the functioning of the timber market. The foundation for their legitimacy as a movement lies in the number of members (Hvenmark 2008). The more forest owners the associations represent, the more influence the association may claim over the timber market and the forestry debate. As advocacy for the organization to other forest owners may be in the interest of the members’ own business deals, a positive relationship between members who deal with their association and their willingness to advocate is expected.

H 13

Members who sell their timber to their forest owners’ association will be more willing than other forest owners to advocate for their timber procurement organization.

Bhattacharya (1998) looked at different levels of engagement of members in their organization and found that members participating in special interest groups showed a significantly lower risk to lapse from the organization. He suggested as a possible explanation that the interest group may become important for the self-identity of the member; in other words that the members who internalize the values of the interest group will be more loyal. Our hypothesis therefore is:

H 14

Members who deal with their forest owners’ association will express a higher level of loyalty to their timber procurement organization than other forest owners will.

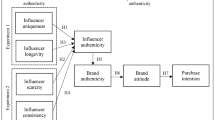

Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual framework in a graphical form. As a distinction is made in the hypotheses H11–H14 between members that actually made the deal with their forest owners’ association and members who dealt with other organizations as well as non-members, the term affiliation with the timber procurement organization was used.

Materials and Methods

Sample

In Sweden, forest owners are required to notify the Swedish Forest Agency of an intended regeneration felling on areas larger than 0.5 hectares, and the notification is often handed in by the company purchasing the timber. This makes it possible to identify forest owners who have been in a business relationship with a timber company. Thus, with the assistance of the Swedish Forest Agency, a random sample of 1025 cases was picked from the register of regeneration felling notifications in 2011. The sample was restricted to those that had been filed by a representative on behalf of an individual forest owner. Based on the information in the sample, it was determined whether the forest owner had made the timber deal with a forest owners’ association. After removing duplicates, notifications concerning land not belonging to an individual, cases with incomplete addresses and properties belonging to deceased people, the final sample consisted of 973 cases.

Data Collection

A questionnaire was used for data collection. The forest owners were asked for their opinions on 45 statements, for information (seven questions) about their contacts for this particular timber deal with a timber procurement organization and for demographic information about themselves (eight questions), including whether they were members of a forest owners’ association. For this study, 14 statements were used to determine the forest owner’s satisfaction with the service provided. These statements were based on the SERVQUAL questionnaire developed by Parasuraman et al. (1988). To measure affective commitment, three statements originating from the work of Price and Arnould (1999) were used. Calculative commitment was determined by four statements adapted from the studies by Price and Arnould (1999) and Han et al. (2008). Advocacy and loyalty were determined by two statements each, all from a study by Han et al. (2008). Table 1 shows the questions used for each construct and the internal consistency between the statements for each construct, measured using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. For the questionnaire, all statements were translated and modified to fit the Swedish forestry context. A scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used for all statements. In the survey, the word “forest company” was used for all types of service providers regardless of the organization’s legal definition. This was explained to the respondents in the cover letter.

The survey was first mailed in November 2012, followed by a second mailing in December to non-responders. Data collection was ended at the beginning of 2013 when 418 responses had been received. After incomplete questionnaire answers had been removed, the analysis was performed on 390 answers (38%). The participation bias analysis in Table 2 showed that forest owners in the age group 30–49 had a relative lower response rate compared to forest owners in the retirement age (65+). Table 3 shows that fewer female forest owners than male forest owners responded.

Description of Respondents

The mean age of the respondents was 60.3 years (with a range of 26–90 years of age). The majority (60.0%) were single owners of the forest property, while 38.7% owned the property jointly with other owners, and 1.3% did not answer the question. In 75.4% of the cases, they had owned the property for longer than 10 years, 13.1% had owned it for between 5 and 10 years, and 10.2% had owned it for less than 5 years (1.3% did not answer). Many were experienced in making timber deals; this had been the first timber deal for only four respondents (1%), 33.3% had made one to three timber deals before, 39.7% had made 4–10 previous timber deals and 14.6% had made more than ten timber deals (11.3% did not answer the question). For 21% of the respondents it was the first time they made a timber deal with the timber procurement organization we asked their opinion on, 40% had dealt with it 2–5 times previously and 37% had dealt with it more than five times before (2% did not answer). The respondents were almost equally divided between three educational levels: 9-year compulsory school (31.0%), upper secondary school (34.1%) and university/college (33.6%), (1.3% did not answer). Respondents that lived in the municipality where their forest is located consisted of 78.2, and 20.8% were absentee forest owners (1% did not respond). Half of the respondents had monetary loans connected to the property, and 59.7% of the respondents stated that they were members of a forest owners’ association.

Analysis

For each respondent, a mean score for the constructs of customer satisfaction, affective commitment, calculative commitment, advocacy and loyalty was determined. Table 4 shows the means and standard deviations as well as the correlations between the constructs. The effect of membership was analysed by dividing the forest owners into three groups according to their affiliation with their timber procurement organizations: members who made a timber deal with their forest owners’ association, members who had chosen another timber procurement organization and non-members. The effects on affective commitment, calculative commitment, advocacy and loyalty were analysed with generalized linear models using the SAS statistical software. The following model was used for affective commitment and calculative commitment:

and for advocacy and loyalty the model was:

where yi is the affective commitment, calculative commitment, advocacy or loyalty of the ith individual, i = 1, 2, …, 390; satisfi is the effect of customer satisfaction of the ith individual, i = 1, 2, …, 390; affili is the effect of affiliation with the timber procurement organization of the ith individual, i = 1, 2, …, 390; calcomi is the effect of calculative commitment of the ith individual, i = 1, 2, …, 390; affcomi is the effect of affective commitment of the ith individual, i = 1, 2, …, 390; calcomi * affcomi is the effect of the interaction between the calculative commitment and affective commitment of the ith individual, i = 1, 2, …, 390; covxi is the value of covariate x when the ith measurement was taken for y. βx is the regression coefficient for covariate x.

The covariates that were included in the model were demographic variables that were found to be significant to account for differences between men and women, residential or absentee forest owners, the experience of the forest owner in doing timber deals, etc.

Results

Table 5 summarizes the results of the hypotheses testing with our models. Affective commitment was found to be significantly affected by customer satisfaction and the affiliation of the forest owners with their timber procurement organization (F = 4.77, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.60). Support was therefore found for hypotheses H1 and H11. The overall mean for affective commitment was 4.67 while the mean affective commitment for members who had dealt with the forest owners’ association was 5.23, that for members who had not dealt with the association was 4.45, and that for non-members was 4.29. Covariates that were found to be significant for affective commitment were the forest owner being a resident on the property or an absentee-owner (F = 5.16, p = 0.0238), the experience (in number of occasions) by the forest owner of dealing with the timber procurement organization (F = 3.97, p = 0.0021) and whether the forest owner had made timber deals with another timber procurement organization before (F = 4.67, p = 0.0315). Resident owners showed a higher mean affective commitment than absentee owners and affective commitment increased with the number of timber deals that forest owners had made with the timber procurer. Forest owners who had previously made deals with other timber procurement organizations had lower mean affective commitment than those that had not changed.

There was also a significant effect of customer satisfaction on calculative commitment (F = 2.72, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.46) which supports hypothesis H2. However, the affiliation of the forest owner did not significantly affect calculative commitment, so no support was found for H12. The overall mean for calculative commitment was 4.47. The significant covariate for calculative commitment was the number of deals that the forest owner had made with the timber procurement organization (F = 6.68, p = 0.0015) and there was a tendency for the education level of the forest owner to affect calculative commitment (F = 2.41, p = 0.0914). Like affective commitment, the mean calculative commitment score increased with the number of deals the forest owners had made with the timber procurement organization. Calculative commitment and affective commitment were positively correlated (ρ = 0.68).

Advocacy was found to be significantly affected by customer satisfaction, affective commitment, calculative commitment, the interaction between affective and calculative commitment and the gender of the forest owner (F = 4.62, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.91). These findings support H3, H4, H5 and H9. Affiliation of the forest owner was however found not to be significant, therefore no support was found for H13. The significant covariate for advocacy was gender (F = 5.08, p = 0.0261).

Loyalty was significantly affected by customer satisfaction, affective commitment, calculative commitment, the interaction between affective and calculative commitment, the affiliation of the forest owner to the timber procurement organization and whether or not the forest owner had previously used another timber procurement organization (F = 5.18, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.93). These findings support hypotheses H6, H7, H8, H10 and H14. The mean score for loyalty was 5.90 among members who dealt with the forest owners’ association, 4.80 for members who did not deal with the forest owners’ association, and 4.92 for other forest owners. Forest owners that had done business with another timber procurement organization before expressed a lower mean loyalty compared to forest owners that had not done business with another organization before (F = 4.03, p = 0.0471).

Discussion

Commitment

The results of this study indicate that relationships in timber deals seem to follow a similar pattern as in other customer relationships to service providers as found by leading marketing researchers such as Fullerton (2003, 2005), Gruen et al. (2000) and Gilliland and Bello (2002) among others. Long-term relationships of timber procurement organizations with forest owners are affected by their commitment to the timber procuring organization and the level of commitment is related to the level of satisfaction with the services provided by the timber procuring organization. The overall level of affective commitment among the forest owners was found to be higher than the calculative commitment (4.7 versus 4.5, see Table 4). According to Fullerton (2003, 2005) and Gruen et al. (2000) affective commitment is a stronger mediator of loyalty than calculative commitment, which suggests that the timber procuring organizations have been quite successful in their attempts to build long term relationships with the forest owners. Affective commitment and calculative commitment were positively correlated, which suggest that a relationship exists between the concepts in this study. Berghäll (2003) found a similar correlation in his study among Finnish forest owners. According to Davis-Sramek et al. (2009) positive calculative commitment may enhance affective commitment as the benefits experienced by the customer may add to the liking of the service provider. Oliver’s (1999) sequential framework suggests however that the process works the other way around, that affective commitment would enhance calculative commitment. Further studies on how forest owners develop calculative and affective commitment among forest owners would not only enlighten what relationship these two concepts have, but also give a greater insight for the sector on how to build long-term relationships.

Resident owners were found to have a significantly greater affective commitment to their timber procurement organization than absentee owners did. This may be explained by differences in the objectives between the two groups. Nordlund and Westin (2011) found that resident owners value production of goods (timber) more highly than absentee owners do, while absentee owners have a tendency to rate preservation higher. This may affect what forest owners consider “good” and “bad” harvesting services, and with that their level of satisfaction and affective commitment. Residency was not found to be significant for calculative commitment which supports the claim that the differences concern shared values rather than benefits. Staal Wästerlund and Kronholm (2014) found a tendency for absentee owners to report more problems with the harvesting operation. Another possible explanation is that the number of contacts with the timber procurer was lower for absentee owners than for resident owners, as in general they live further away. According to Price and Arnould (1999), structural opportunities for sociability are required for the formation of affective relationships. Fullerton (2003), Morgan and Hunt (1994) and Garbarino and Johnson (1999) pointed out the importance of trust in the development of commitment. Trust was not included in our study, but it may explain why forest owners who had changed timber procurement organizations had lower affective commitment, as they may have had negative experiences initiating the change; therefore, they may need time to develop trust in the new timber procurement organization. That calculative commitment, with the meaning we have given it in this study (more benefits, better service), may grow with the number of timber deals seems logical because the development of such rationality may require longer exposure.

Satisfaction

This study also found, like Gruen et al. (2000), that there was a direct effect of customer satisfaction on loyalty which suggests that commitment is only a partial mediator in the development of loyalty. Gruen et al. (2000) suggested that this is a result of the change in society that makes customers increasingly more self-centered and therefore very focused on today’s performance. Balaji (2015) suggest that the impact of customer satisfaction on loyalty will decrease as the length of the relationship between the partners increases. In this study however, we did not find that the number of deals made by the forest owner with the timber procuring organization had a significant impact. Garbarino and Johnson (1999) found that the dependency of loyalty on satisfaction and commitment varied according to the type of customer. For customers who only occasionally used the service, intention to reuse the service was highly dependent on customer satisfaction, while for regular users of the service provider, loyalty was highly dependent on commitment. How regular a forest owner makes a timber deal depends to some extent on the size of the property and for most forest owners it takes years between such deals (Lönnstedt 1997). Timber procurement organizations often aim to stay in contact with forest owners between timber deals and these customer management activities may have a significant impact on the development of commitment that is not accounted for in this study. Further studies on this aspect would be highly relevant for the sector.

According to Heskett et al. (2008) customer satisfaction is influenced by the value of the services provided to the customer. The forest owners participating in this study expressed reasonably high satisfaction with the services provided by the timber procurement organization, as shown in Table 4 (5.6 on a scale from 1 to 7). Heskett et al. (2008) pointed out the importance of customer satisfaction for the development of loyalty by referring to the findings of a company study that very satisfied customers were six times more likely to repurchase than customers who were merely satisfied. According to Bloemer and Kasper (1995) the development of loyalty is dependent on the customer being consciously aware on their level of satisfaction. So merely meeting the expectations of the customer is not enough as this study is also revealing.

Membership as a moderator for commitment, advocacy and loyalty

Members of a forest owners’ association who have made their timber deal with the association showed higher levels of affective commitment and loyalty than members who did not make a deal with the association, or non-members. Yet no effect of membership was found on calculative commitment even with the positive formulation of the statements in this study. This suggests that member loyalty to the organization is mainly mediated through affective commitment. This accords with the findings of Gruen et al. (2000) and Vincent and Webster (2013). Yet at the same time, it is somewhat surprising that monetary investment in the associations as well their expressed objective to support the profitability of their members’ forest ownership is not transferred into a greater calculative commitment than is evident in companies that do not have these specific objectives. It also seems at first glance to contradict the results of Österberg and Nilsson (2009), who found that the commitment of farmers to their cooperatives was largely dependent on the profitability. Yet they also found that the perception of participation in the governance of the co-operative among members was essential for their commitment. Moreover, Gruen et al. (2000) and Vincent and Webster (2013) found that recognition by the organization of contributions was important for the development of affective commitment. Therefore, Österberg and Nilsson (2009) advise large co-operatives to invest in well-functioning member democracy and communication processes. The results of this study endorse these recommendations.

The hypothesis that members would show greater willingness to advocate for their association was based on the old argument that founded the associations in the first place, that “together we are strong”. Yet the results showed that advocacy is not affected by membership. Lacey and Morgan (2009) found that while commitment increased willingness to advocate, membership of a loyalty programme did not. Their interpretation was that loyalty programmes are often created by the company; they are not something that customers actively seek. Kronholm and Staal Wästerlund (2013) found that membership is often offered as part of the timber deal, so it is often initiated by the associations. Kronholm and Staal Wästerlund (2013) also found that members do not seem to believe that it is their task to market the association.

Study Limitations

This study used a limited number of statements to measure the concepts of affective commitment, calculative commitment, advocacy and loyalty. These statements were based on earlier investigations by well-established marketing researchers, with similar objectives using similar numbers of statements per concept, yet among a much larger group of respondents. To test the internal consistency of the questions, Cronbach alpha (α) coefficients were calculated. According to Gruen et al. (2000), the accepted minimum level of α to indicate acceptable reliability is 0.7, and all constructs exceed this level. Yet advocacy that was constructed by only two questions is close to this minimum level. The choice of whether forest owners recommend the service provider to somebody else or the intention to give feedback do not seem to be very closely related in this study. This study used measures of service quality to determine customer satisfaction. While there is ample evidence that service quality is a strong antecedent for customer satisfaction (Cronin and Taylor 1992; Setó-Pamies 2012 among other), we did not specifically asked the respondents to rate their satisfaction. All statements were translated from English to Swedish. While great effort was made to preserve the essence of the statements in the translations, there is always a risk of slight differences in the interpretation of the statements by the respondents of this study compared with the respondents of the original studies because of differences in the local culture of the sample. The 38% response rate to the questionnaire may be regarded as acceptable, but some bias must be taken into account, as the majority of the respondents were elderly male forest owners. According to Berlin et al. (2006) members of forest owners’ associations value income of their forest higher than non-members which is reflected in this study by the high level of membership among the participants (59.7%) compared to general membership level among forest owners (37%). A potentially important covariate not included in the analysis is the size of the property, as this affects the potential for harvesting activities of the forest owner and the possibility that he/she will develop commitment and loyalty. This could not be included because of a miscommunication with the Swedish Forest Agency. This study was conducted from a customer perspective of harvesting services with only limited consideration that a timber deal in the majority of cases is initiated by the forest owner to gain a favourable profit. The marketing literature does not reveal clear differences in the commitment—loyalty theories in customer behaviour between ordinary customers and service suppliers compared with business-to-business relationships. However, further research concerning whether the kind of relationship between forest owners and timber procurement organizations affects commitment and loyalty is recommended.

Conclusions

Forest owners seem to behave similar to customers when selling their timber to a timber procurement organization. Like customers, loyalty of forest owners as suppliers to timber procurement organizations is mediated by the owners’ commitment to the organization. It was also found that affective commitment was a stronger mediator than calculative commitment. In practice this implies that for timber procurement organizations interested in establishing long term relationships, giving focus to sharing values with the forest owners might be more beneficial than focusing on benefits offered to the forest owner. This is especially true for forest owners’ associations where loyal members willing to contribute to the association form the core of the organization.

References

Balaji MS (2015) Investing in customer loyalty: the moderating role of relational characteristics. Serv Bus 9:17–40. doi:10.1007/s11628-013-0213-y

Bansal HS, Irving PG, Taylor SF (2004) A three-component model of customer commitment to service providers. J Acad Mark Sci 32:234–250. doi:10.1177/0092070304263332

Berghäll S (2003) Developing and testing a two-dimensional concept of commitment—explaining the relationship perceptions of an individual in a marketing dyad. Dissertation, Department of Forest Economics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki

Berlin C, Lidestav G, Holm S (2006) Values placed on forest property benefits by Swedish NIPF owners: differences between members in forest owners associations and non-members. Small-Scale For Econ Man Policy 5:83–96. doi:10.1007/s11842-006-0005-5

Bhattacharya CB (1998) When customers are members: customer retention in paid membership contexts. J Acad Mark Sci 26:31–44. doi:10.1177/0092070398261004

Bloemer JMM, Kasper HDP (1995) The complex relationship between consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty. J Econ Psychol 16:311–329. doi:10.1016/0167-4870(95)00007-B

Cronin JJ, Taylor SA (1992) Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. J Mark 56:55–68. doi:10.2307/1252296

Davis-Sramek B, Droge C, Mentzer JT, Myers MB (2009) Creating commitment and loyalty behavior among retailers: what are the roles of service quality and satisfaction? J Acad Mark Sci 37:440–454. doi:10.1007/s11747-009-0148-y

Dwyer R, Schurr PH, Oh S (1987) Developing buyer-seller relationships. J Mark 51:11–27. doi:10.2307/1251126

Fullerton G (2003) When does commitment lead to loyalty? J Serv Res-US 5:333–344. doi:10.1177/1094670503005004005

Fullerton G (2005) The impact of brand commitment on loyalty to retail service brands. Can J Adm Sci 22:97–110. doi:10.1111/j.1936-4490.2005.tb00712.x

Garbarino E, Johnson MS (1999) The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J Mark 63:70–87. doi:10.2307/1251946

Gilliland DI, Bello DC (2002) Two sides to attitudinal commitment: the effect of calculative and loyalty commitment on enforcement mechanisms in distribution channels. J Acad Mark Sci 30:24–43. doi:10.1177/03079450094306

Gremler DD, Brown SW (1996) Service loyalty: its nature, importance, and implications. In: Edvardsson B, Brown SW, Johnston R, Scheuing EE (eds) Advancing service quality: a global perspective. St. John’s University, International service quality association, New York, pp 171–180

Gruen TW, Summers JO, Acito F (2000) Relationship marketing activities, commitment, and membership behaviors in professional associations. J Mark 64:34–49. doi:10.1509/jmkg.64.3.34.18030

Han X, Kwortnik R Jr, Wang C (2008) Service loyalty: an integrative model and examination across service contexts. J Serv Res-US 11:22–42. doi:10.1177/1094670508319094

Häyrinen L, Mattila O, Berghäll S, Toppinen A (2015) Forest owners’ socio-demographic characteristics as predictors of customer value: evidence from Finland. Small-Scale For 14:19–37

Heskett JL, Jones TO, Loveman GW, Sasser WE Jr, Schlesinger LA (2008) Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harv Bus Rev 86(7–8):118–129

Hvenmark J (2008) Reconsidering membership: a study of individual members’ formal affiliation with democratically governed federations. Dissertation, Stockholm School of Economics, Stockholm

International Cooperative Alliance (2015) http://ica.coop/en/whats-co-op/co-operative-identity-values-principles. Accessed 15 July 2015

Jacoby J, Chestnut RW (1978) Brand loyalty: measurement and management. Wiley, New York

Kärhä K, Oinas S (1998) Satisfaction and company loyalty as expressed by nonindustrial private forest owners towards timber procurement organizations in Finland. Silva Fenn 32:27–42. doi:10.14214/sf.698

Keiningham TL, Frennea CM, Aksoy L, Buoye A, Mittal V (2015) A five-component customer commitment model: implications for repurchase intentions in goods and services industries. J Serv Res-US 18:433–450. doi:10.1177/1094670515578823

Kim J, Morris JD, Swait J (2008) Antecedents of true loyalty. J Advert 37:99–117. doi:10.2753/JO0091-3367370208

Kittredge D (2003) Private forestland owners in Sweden—large-scale cooperation in action. J For 101:41–46

Kronholm T, Staal Wästerlund D (2013) District council members and the importance of member involvement in organization renewal processes in Swedish forest owners’ associations. Forests 4:404–432. doi:10.3390/f4020404

Lacey R, Morgan RM (2009) Customer advocacy and the impact of B2B loyalty programs. J Bus Ind Mark 24:3–13. doi:10.1108/08858620910923658

Lönnstedt L (1997) Non-industrial private forest owners’ decision process: a qualitative study about goals, time perspective, opportunities and alternatives. Scand J For Res 12:302–310. doi:10.1080/02827589709355414

Mattila O, Toppinen A, Tervo M, Berghäll S (2013) Non-industrial private forest service markets in a flux: results from a qualitative analysis on Finland. Small-Scale For 12:559–578. doi:10.1007/s11842-012-9231-1

Moorman C, Zaltman G, Deshpande R (1992) Relationship between providers and users of market research—the dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J Mark Res 29:314–328. doi:10.2307/3172742

Morgan RM, Hunt SD (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J Mark 58:20–38. doi:10.2307/1252308

Nordlund A, Westin K (2011) Forest values and forest management attitudes among private forest owners in Sweden. Forests 2:30–50. doi:10.3390/f2010030

Oliver RL (1999) Whence consumer loyalty? J Mark 63:33–44. doi:10.2307/1252099

Oliver RL (2010) Satisfaction—a behavioral perspective on the consumer. M. E. Sharpe, Armonk

Österberg P, Nilsson J (2009) Members’ perception of their participation in the governance of cooperatives: the key to trust and commitment in agricultural cooperatives. Agribusiness 25:181–197. doi:10.1002/agr.20200

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml V, Berry L (1988) SERVQUAL: multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perception of service quality. J Retail 64:12–40

Price LL, Arnould EJ (1999) Commercial friendships: service provider-client relationships in context. J Mark 63:38–56. doi:10.2307/1251973

Setó-Pamies D (2012) Customer loyalty to service providers: examining the role of service quality, customer satisfaction and trust. Total Qual Manage 23:1257–1271. doi:10.1080/14783363.2012.669551

Shukla P, Banerjee M, Singh J (2016) Customer commitment to luxury brands: antecedents and consequences. J Bus Res 69:323–331. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.004

Staal Wästerlund D, Kronholm T (2014) Market analysis of the harvesting services engaged by private forest owners in Sweden. In: Roos A, Lönnstedt L, Nord T, Gong P, Stendahl M (eds) Proceedings of the biennial meeting of the Scandinavian society of forest economics Uppsala. Sweden, May 2014. Scandinavian Forest Economics no. 45, 2014, pp 111–119

Stryjan Y (1994) Understanding cooperatives: the reproduction perspective. Ann Publ Coop Econ 65:59–79

Swedish Forest Agency (2014) Skogsstatistiska årsboken 2014 [Swedish statistical yearbook of forestry]. Swedish Forest Agency, Jönköping

Vincent NA, Webster CA (2013) Exploring relationship marketing in membership associations. J Mark 47:1622–1640. doi:10.1108/EJM-06-2011-0296

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brattåsstiftelsen for their financial support for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Staal Wästerlund, D., Kronholm, T. Family Forest Owners’ Commitment to Service Providers and the Effect of Association Membership on Loyalty. Small-scale Forestry 16, 275–293 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-016-9359-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-016-9359-5