Abstract

Purpose

Despite the well-established risks associated with persistent smoking, many cancer survivors who were active smokers at the time of cancer diagnosis continue to smoke. In order to guide the development of tobacco cessation interventions for cancer survivors, a better understanding is needed regarding post-diagnosis quitting efforts. Thus, we examined quitting and reduction efforts and interest in cessation resources among cancer survivors who self-identified as current smokers at the time of diagnosis.

Methods

We conducted analyses of survey participants (n = 54) who were current smokers at the time of cancer diagnosis and were continued smokers at the time of assessment. We also conducted semi-structured interviews (n = 21) among a subset of those who either continued to smoke or quit smoking post-cancer diagnosis.

Results

Among our survey participants, 22.2 % had ever used behavioral cessation resources and 66.7 % had use pharmacotherapy, while 62.8 % had interest in future use of behavioral cessation resources and 75.0 % had interest in pharmacotherapy. The majority reported some quitting efforts including making quit attempts, using cessation medications, and reducing their daily cigarette consumption. Semi-structured interview data revealed various strategies used to aid in smoking reduction and cessation as well as variability in preferences for cessation resources.

Conclusions

Cancer patients who smoke following diagnosis often engage in smoking reduction and cessation-related behaviors, which may reflect their motivation to reduce their smoking-related risks. They also report high interest in cessation resources. Thus, it is important to explore the acceptability and effectiveness of different cessation intervention components among this group.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Cancer survivors who smoke demonstrate actions toward harm reduction and cessation. They should inquire about potential resources that might facilitate their efforts among their healthcare providers and enlist support and advice from others around them to bolster their efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over 67 % of individuals diagnosed with cancer in 2009 can expect to survive at least 5 years, joining the 11 million cancer survivors in the U.S. [1]. Unfortunately, second primary malignancies among this high-risk group account for 16 % of all cancer incidence [2]. Thus, assessing and intervening on health behaviors that place individuals at risk for secondary malignancies is critical in reducing morbidity and mortality among cancer survivors in particular. Unfortunately, 15.1 % of all cancer survivors report being current smokers [3]. At the time of diagnosis, estimated rates on the prevalence of current smoking vary greatly ranging from approximately 45–75 % depending upon a number of factors including type of cancer [4]. For instance, continued smoking appears higher among patients diagnosed with tobacco-related cancers (27 %) compared to other cancer survivors (16 %) [5].

Continued smoking after cancer diagnosis has substantial medical risks. First, continued smoking may reduce treatment effectiveness [6] and increase mortality [7], whereas quitting smoking increases odds of both treatment efficacy and survival [7–11]. Second, continued smoking may worsen side effects of treatment [6, 12–15], while cessation is related to enhanced pulmonary and immune functioning and wound healing [16–18]. Third, smokers diagnosed with cancer (smoking-related and nonsmoking-related) increase their risk of a second malignancy at the same site or another site if they continue to smoke [7, 19–24], particularly when initial prognosis is more favorable [25–27]. Cessation unequivocally reduces the risk of a second cancer [26, 28].

Given that smoking cessation within this population confers a number of health benefits, assessing smoking status and encouraging quit attempts is recommended as a standard of quality cancer care [29]. However, some smokers may be unable or unwilling to quit. Unfortunately, the few clinical interventions conducted have failed to produce significant outcomes [4, 30–35]. For those who continue to smoke following diagnosis, at least two interpretations are possible. On one hand, increased psychosocial stressors (e.g., anxiety, depression, fatalism) may undermine interest or motivation to quit, leading to few changes in smoking behavior. On the other hand, continued smokers may be trying to quit, but unable to do so, leading them to engage in what is perceived as less risky smoking (i.e., harm reduction).

Within the tobacco cessation field, there is growing yet controversial acceptance regarding the importance of harm reduction. Especially relevant for those smokers unwilling or unable to quit [36], harm reduction may reduce adverse health risks [37–39]. Despite the relevance of harm reduction to cancer survivors who may have difficulty quitting, very little research has focused on quitting efforts or efforts toward harm reduction among cancer survivors. Harm reduction methods may include switching to noncombustible tobacco products, reducing the number of cigarettes smoked per day, or the use of cigarette-like products that deliver nicotine but have lower amounts of tobacco toxins. Individuals may also concurrent use of nicotine replacement therapy in order to decrease cigarette consumption. Harm reduction efforts within a cancer population warrants further attention.

Given the risks of continued smoking among cancer survivors, it is critical to understand what strategies cancer survivors have used or might use to make strides toward quitting smoking or harm reduction. Thus, the current study aimed to examine quitting and reduction efforts and interest in cessation resources among cancer survivors who self-identified as current smokers at the time of diagnosis.

Methods

The current study used a mixed methods approach to address our study aims. Specifically, we identified cancer patients using electronic medical records (EMR) from a National Cancer Institute (NCI) designated cancer center in a large southeastern city in Fall 2010. Individuals with a history of smoking and diagnosed with a smoking-related cancer (i.e., lung, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, bladder, stomach, cervix, kidney, pancreas, acute myeloid leukemia) from 2005 to 2010 were recruited to complete a mail-based survey. We then purposively recruited a subset of survey participants for in-depth semi-structured interviews to gain more comprehensive information regarding cessation and harm reduction efforts among cancer survivors who were smoking at the time of cancer diagnosis and subsequently either quit smoking or continued to smoke. This study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Survey research

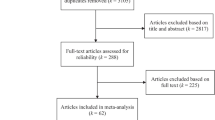

We mailed surveys (including a pre-address, stamped envelope) to 798 potential participants, and research staff made follow-up phone calls to encourage participation one week later (see Fig. 1). We received notifications that 72 of these individuals were deceased, and 113 had incomplete or incorrect addresses and/or phone numbers. A total of 139 individuals completed and returned the survey (22.7 % response rate; n = 139/613). Of the respondents, 54 reported smoking at the time of diagnosis and at survey administration; this subset is the focus of these quantitative analyses. Due to the incomplete nature of smoking-related information in the EMR, we were unable to determine any differences between respondents and nonrespondents in terms of smoking history. However, our sample was proportionately representative of gender, ethnicity, age, time since diagnosis, and cancer type selected for inclusion in this study.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

These included age, gender, ethnicity, education level, household income, employment status, marital status, and insurance coverage. Ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic White, Black, or Other due to the small numbers of participants who reported other races/ethnicities.

Cancer-related factors

We assessed type of cancer, stage of cancer at diagnosis, and date of diagnosis of current cancer. We also asked, “Did/does your treatment protocol include chemotherapy? Surgery? Radiation?” with response options of “No; Yes, I completed it; or Yes, I am currently going through it.”

Smoking-related factors

To assess smoking status, participants were asked, “Were you smoking at the time of your cancer diagnosis?” and “In the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke a cigarette (even a puff)?” This latter question has been used to assess tobacco use in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) [40] and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) [41]. Those who reported smoking on at least 1 day in the past 30 days were considered current smokers [40, 41]. We also asked, “On the days that you smoke, how many cigarettes do you smoke on average?” We administered the six-item Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence, a widely used measure of nicotine dependence with established reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.61) [42]. To assess confidence and motivation to quit, participants were asked, “On a scale of 0 to 10 with 0 being ‘not at all confident’ and 10 being ‘extremely confident,’ assuming you want to, how confident are you that you could quit smoking cigarettes starting this week and continuing for at least 1 month?” and “On a scale of 0 to 10 with 0 being ‘I don’t want to at all’ and 10 being ‘I really want to,’ how much do you want to quit smoking cigarettes?” [43, 44]. Participants were also asked, “During the past 12 months, how many times have you stopped smoking for 1 day or longer because you were trying to quit smoking?” [45]. This variable was dichotomized as having made at least one quit attempt in the past year versus not having made an attempt to quit. Readiness to quit was assessed by asking, “What best describes your intentions regarding quitting smoking?” Response options were “never expect to quit,” “may quit in the future, but not in the next 6 months,” “will quit in the next 6 months,” and “will quit in the next month” [46]. For the present study, this variable was dichotomized as intending to quit in the next 30 days versus all other responses.

Prior use of cessation strategies

Participants were asked, “Have you ever used any of the following methods to help you quit smoking? (Check all that apply): I have never tried to quit smoking; I quit on my own, did not use anything; Talked to a doctor or nurse for help with quitting; Talked to a counselor; Attended a class or group program; Telephone counseling; Internet or online program; Nicotine patch; Nicotine gum; Nicotine lozenges; Other Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) products; Zyban, Wellbutrin, or Bupropion; Chantix or Varenicline.”

Interest in cessation strategies

Participants were asked, “If you were going to try to quit smoking, how interested would you be in the following ways of getting help in quitting? (Check all that apply): Attending a group meeting or class; Having a meeting with a stop smoking counselor; Using a telephone program; Visiting a stop smoking website; Nicotine patch; Nicotine gum; Nicotine lozenges; Zyban or Wellbutrin; or Chantix or Varenicline.” Response options included: not at all interested, not very interested, somewhat interested, interested, or very interested. Responses were dichotomized as not interested (i.e., not at all or not very interested) versus interested (somewhat interested, interested, very interested).

Harm reduction strategies

Participants were asked to respond yes/no if, since their diagnosis, they had done any of the following to decrease health risks from smoking: (a) changed to a different cigarette brand, (b) decreased the number of cigarettes smoked, (c) changed to smoking only on some days, (d) switched to a lighter tar cigarette, and/or (e) set a limit for how many cigarettes they smoked each day. Participants were also asked: (a) how often they tried to limit smoking and (b) how often they smoked less than half a cigarette to decrease the health risks from smoking. Responses to these latter questions ranged from 0 (Never) to 4 (Always).

Data analysis

Participant characteristics, prior use of harm reduction and cessation strategies/resources, and interest in future use of cessation strategies and resources were summarized using descriptive statistics. We conducted exploratory bivariate analyses examining associations between smoking-related factors (smoking frequency/level, nicotine dependence, motivation/confidence in quitting, recent quit attempts, readiness to quit) and prior utilization of harm reduction and cessation strategies and resources and interest in future use of cessation strategies and resources. SPSS 19.0 was used for all data analyses. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 for all tests.

Semi-structured interview research

In Spring 2011, we conducted 21 telephone-based semi-structured interviews with individuals recruited from the initial survey research. We opted to include both those who quit smoking since diagnosis and those who continued to smoke in order to gain more comprehensive information regarding cessation and harm reduction efforts among cancer survivors who successfully quit or were unable to quit. The sample for the qualitative data collection included a total of 21 participants, with 15 reporting quitting smoking post-cancer diagnosis and six reporting current (past 30-day) smoking. Four were diagnosed with lung cancer, three with head and neck cancer, and 14 with kidney, pancreas, bladder, or colorectal cancer (i.e., other smoking-related cancers). We were unable to recruit participants diagnosed with lung, head, or neck cancer who were current smokers, perhaps due to the much greater likelihood of this patient population successfully achieving cessation [47]. Nine of those diagnosed with other smoking-related cancers had successfully quit post-diagnosis, and five continued to smoke after diagnosis.

Prior to beginning the semi-structured interviews, participants were given a thorough explanation of the study and if interested provided verbal consent. A trained interviewer followed a semi-structured interview guide which included the following questions: “What has helped you when you have tried to quit smoking? What resources have you used when you have tried to quit smoking?” The interviewer also probed about resources or facilitators for cessation used since cancer diagnosis. The interviewer also asked, “What are the resources come to mind when you think about trying to get help with quitting? What do you think might help you to quit smoking? If you were to talk to someone about smoking, who would you prefer to talk to? How would you feel about in-person vs. telephone-based counseling?” Each session lasted about 60 min. All sessions were audiotaped and transcribed. Individuals who participated in the structured interviews received $30.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed according to the principles outlined in Morgan and Krueger [48]. Transcripts were independently reviewed by the PI, a trained Master of Public Health staff, and a research assistant to generate preliminary codes using an inductive process. The research team used an iterative process to develop a master coding structure [49, 50]. Primary (i.e., major topics explored) and secondary codes (i.e., recurrent themes within these topics) were then clearly defined in a codebook that was used to independently code each transcript. Qualitative data was coded and organized using NVivo 9.0 (QSR International, Cambridge, MA). Content analysis was conducted by two independent coders to identify themes, and matrices were constructed to help identify patterns by smoking status (nondaily versus daily smoker). Coders resolved any discrepancies through discussions. Intra-class correlations for context were 0.92. Themes were then identified and agreed upon between the PI and the coders, and representative quotes were selected.

Results

Survey research

Table 1 presents participant characteristics. This population smoked largely on a daily basis and smoked 16 cigarettes per day on average. Although less than one fourth of participants had made a quit attempt in the past year and a tenth of participants had never attempted to quit, over two-thirds intended to quit smoking in the next month. While participants were motivated to quit smoking, they reported low confidence in quitting smoking.

Table 2 highlights prior use of cessation and harm reduction strategies and interest in future use of cessation strategies. Of the 54 current smokers, 22.2 % had ever used behavioral cessation resources, and 66.7 % had use pharmacotherapy. Overall, 62.8 % had interest in future use of behavioral cessation resources, and 75.0 % had interest in future use of pharmacotherapy. In terms of harm reduction strategies since cancer diagnosis, 20.4 % switched cigarette brands, 53.7 % decreased cigarette consumption, 14.8 % switched to only smoking on some days, 24.1 % switched to lighter tar cigarettes, and 55.6 % limited how much they smoke to decrease their health risks from smoking. While some associations existed between smoking-related factors and prior use of harm reduction and cessation strategies/resources and interest in future use of cessation strategies/resources were marginally significant, no associations met statistical significance.

Structured interview research

The average age of semi-structured interview participants was 60.29 years (SD = 7.95; range = 48–77 years). The sample for the qualitative data collection included 9 (42.9 %) males and 12 (57.1 %) females. The majority of participants were white (n = 17; 81 %), 2 (9.5 %), were African American, and 2 (9.5 %) identified as belonging to another race. Regarding education, 7 (33.3 %) had a high school degree or GED or less education, 6 (28.6 %) had some college, and 8 (38.1 %) were college graduates or graduate degree earners. In terms of employment, 9 (42.9 %) worked at least part-time, with the remaining 12 (57.1 %) being out of work, disabled, or retired.

Behavioral strategies used

Participants reported a range of behavioral strategies that they used in their cessation attempts (see Table 3). First, many reported the importance and utility of “willpower.” They also discussed using distraction to get through tempting situations and cravings. Some participants also discussed the use and importance of prayer in their efforts to quit smoking. They also reported avoiding triggers for smoking and systematically reducing cigarette consumption. Finally, they reported using substitutes to replace their cigarettes during moments of craving, which included both non-food substitutes (e.g., straws, inactive cigarettes, e-cigarettes) and food substitutes (e.g., sunflower seeds, candy).

Social support

In terms of social support, many participants endorsed the importance of social support. Interestingly, encouragement from loved ones and cessation among those close to them was identified as helpful in providing a less tempting environment.

Cessation pharmacotherapy

Several participants reported experiences with and interest in pharmacotherapy. In general, participants reported experiencing benefit from using NRT, Zyban, and Chantix, although several participants mentioned that they had difficulty adhering to pharmacotherapy, particularly NRT. They also endorsed these products as potentially helpful for others.

Behavioral counseling

In terms of preference for counseling modality, some participants identified the comfort and intimacy of in-person counseling, while other participants endorsed the convenience of telephone-based counseling due to the restrictions on their mobility (e.g., feeling ill). In terms of the interventionist, there was a wide range of preferences. Some suggestions for potential facilitators of group cessation counseling included cessation experts, whereas others identified someone else attempting to quit smoking, a successful quitter, or a fellow cancer survivor who had smoked and either quit or is currently attempting to quit as ideal interventionists.

Discussion

The current study presents novel data regarding prior use of harm reduction and cessation strategies and resources and interest in future use of differing cessation strategies and resources among survivors of smoking-related cancers. Interestingly, we found high rates of harm reduction use and high interest in cessation resources. However, our sample indicated low confidence in quitting, and only 23 % of our sample reported a quit attempt in the past year, while national statistics indicate that roughly 40 % of smokers have tried to quit smoking in the past year [51, 52]. These findings illustrate that cancer patients who are not fully abstinent or not actively attempting to quit may still be motivated to reduce the risks of smoking by engaging in harm reduction strategies and remaining open to the idea of using cessation resources in the future.

In terms of resource utilization, roughly one-fifth of participants had ever used behavioral interventions, which is a higher rate than documented among the general population [53]. In our sample, the majority of these individuals had talked to a doctor or nurse, and very few used other behavioral resources. However, nearly one-half reported interest in counseling (either group, individual, or telephone-based). Qualitative findings reported a wide range of preferences for interventionists, including smoking cessation experts, healthcare providers, peer cancer survivors, and peer smokers also trying to quit smoking. They also reported that they appreciated the personalization of in-person counseling but also valued the convenience of telephone-delivered counseling.

Regarding pharmacotherapy, there was a high rate of interest in making future use of cessation pharmacotherapy. Qualitative findings also suggested largely favorable experiences among those who had tried different types of pharmacotherapy options. In addition, over two-thirds had previously used some kind of pharmacotherapy, which is similar to utilization rates in the general population [53]. A large proportion (42.6 %) reported prior usage of bupropion or varenicline. However, the most commonly used form of pharmacotherapy was the NRT patch followed by the NRT gum. This is a concern given the recent research indicating that nicotine may actually promote tumor growth and metastasis in lung cancer [54]. Clinicians should warn patients of this risk and potentially urge patients to use non-nicotine delivering pharmacotherapy to aid in cessation.

There was also a high rate of harm reduction method utilization. Over half of participants reduced their level of smoking, which was also highlighted in the qualitative interviews. This strategy may have been used in order to work toward cessation, even if cessation was not accomplished. Of concern, one fourth reported switching to lighter tar cigarettes, suggesting these cancer survivors held an erroneous belief that this strategy reduces the health risks of smoking [55–60]. Thus, it is important to understand harm reduction strategies that smokers might use in order to address any misunderstandings about the benefits of engaging in such behaviors.

In addition, clinicians should consider providing cessation pharmacotherapy and other cessation resources for smokers unwilling or unmotivated to quit. Prior literature indicates that concurrent use of cigarettes and nicotine replacement therapy might promote cessation [39, 61, 62]. For example, one study [61] found that nicotine gum promoted cessation in healthy smokers smoking at least 15 cigarettes per day and who were unwilling to quit. Among reducers, the toxin intake correlated with reduced cigarette consumption. Despite these findings, the provision of cessation resources is typically contingent on quitting smoking or expressing a desire to do so in near future. Thus, clinicians should conduct a more thorough assessment of motivation to quit smoking or engage in other strategies that might facilitate cessation and provide support accordingly.

The current study has important implications for research and practice. Research should more systematically examine the effectiveness of various combinations of pharmacotherapies and behavioral counseling strategies. This is critical, given that cancer survivors seem to be using several cessation strategies and resources concurrently, which is likely indicative of low level of confidence in their ability to quit smoking. It is also critical to explore the impact of behavioral counseling delivered by different interventionists and via different modes (e.g., in person versus via telephone). Furthermore, more research should focus on the harm reductions strategies used and the beliefs about their effectiveness in reducing health risks among cancer survivors. In clinical practice, it is critical to be mindful that most cancer survivors who smoke are interested in quitting smoking but have low confidence in their ability to quit and high interest in cessation resources. Cessation services must be developed to meet cancer survivors’ varied cessation needs and preferences. They may also be making progress toward cessation by using harm reduction strategies, particularly cutting down on daily smoking.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, despite the fact that this sample reflects the characteristics of the cancer survivor population from the medical setting from which they were recruited, it may not generalize to other cancer survivor populations. Second, the survey response rate was 22.7 %, which may seem low and might suggest responder bias. However, it is difficult to ascertain the true denominator of the response rate. Although the medical records contained some information on current patient vital status, several families notified us that the survey had been sent to a deceased patient; others who were deceased may not have been reported to us. We also cannot assume that the medical records included up-to-date contact information; thus, additional surveys may not have reached the intended individuals. Our survey also assessed “ever use” of the several smoking cessation resources rather than post-diagnosis use. Future research should examine post-diagnosis use of cessation resources and strategies. Similarly, our survey questionnaire did not assess utilization of other harm reduction strategies, such as the use of smokeless tobacco or electronic cigarettes. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of this study limits the extent to which we can make causal attributions.

Conclusions

Cancer patients who smoke following diagnosis often engage in harm reduction and cessation-related behaviors, likely reflective of their motivation to reduce their smoking-related risks. They also report high interest in use of cessation resources. Thus, future research should explore the acceptability and effectiveness of different cessation intervention components. It is also critical to examine the beliefs cancer survivors hold regarding the effectiveness of harm reduction behaviors. Moreover, clinicians should be attentive to supporting smoking reduction behaviors among cancer survivors who smoke, particularly among those who are unwilling or unmotivated to quit smoking.

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures, 2011. http://www.cancer.org/Research/CancerFactsFigures/CancerFactsFigures/cancer-facts-figures-2011. Accessed 10 July 2012.

Travis LB, Rabkin CS, Brown LM, Allan JM, Alter BP, Ambrosone CB, et al. Cancer survivorship—genetic susceptibility and second primary cancers: research strategies and recommendations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:15–25.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance of Demographic Characteristics and Health Behaviors Among Adult Cancer Survivors—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:1–23.

Cooley ME, Lundin R, Murray L. Smoking cessation interventions in cancer care: opportunities for oncology nurses and nurse scientists. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2009;27:243–72.

Underwood JM, Townsend JS, Tai E, White A, Davis SP, Fairley TL. Persistent cigarette smoking and other tobacco use after a tobacco-related cancer diagnosis. J Cancer Surviv. 2012; doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0230-1

Des Rochers C, Dische S, Saunders MI. The problem of cigarette smoking in radiotherapy for cancer in the head and neck. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1992;4:214–6.

Parsons A, Daley A, Begh R, Aveyard P. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5569.

Browman GP, Wong G, Hodson I, Sathya J, Russell R, McAlpine L, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on the efficacy of radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:159–63.

Stevens MH, Gardner JW, Parkin JL, Johnson LP. Head and neck cancer survival and life-style change. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:746–9.

Johnston-Early A, Cohen MH, Minna JD, Paxton LM, Fossieck Jr BE, Ihde DC, et al. Smoking abstinence and small cell lung cancer survival. An association. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1980;244:2175–9.

Mason DP, Subramanian S, Nowicki ER, Grab JD, Murthy SC, Rice TW, et al. Impact of smoking cessation before resection of lung cancer: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database Study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:362–71.

Chelghoum Y, Danaïla C, Belhabri A, Charrin C, Le QH, Michallet M, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on the presentation and course of acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1621–7.

Karim AB, Snow GB, Siek HT, Njo KH. The quality of voice in patients irradiated for laryngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 1983;51:47–9.

Rugg T, Saunders MI, Dische S. Smoking and mucosal reactions to radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1990;63:554–6.

Tyc VL, Hudson MM, Hinds P, Elliott V, Kibby MY. Tobacco use among pediatric cancer patients: recommendations for developing clinical smoking interventions. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2194–204.

Gritz ER, Kristeller J, Burns DM. Treating nicotine addiction in high-risk groups and patients with medical co-morbidity. In: Orleans CT, Slade J, editors. Nicotine addiction: principles and management. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. p. 279–309.

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General, 1983. http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/B/T/D/ Accessed 10 July 2012.

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General. http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/B/C/T/. Accessed 10 July 2012.

Wynder EL, Mushinski MH, Spivak JC. Tobacco and alcohol consumption in relation to the development of multiple primary cancers. Cancer. 1977;40:1872–8.

Day GL, Blot WJ, Shore RE, McLaughlin JK, Austin DF, Greenberg RS, et al. Second cancers following oral and pharyngeal cancers: role of tobacco and alcohol. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:131–7.

Do KA, Johnson MM, Doherty DA, Lee JJ, Wu XF, Dong Q, et al. Second primary tumors in patients with upper aerodigestive tract cancers: joint effects of smoking and alcohol (United States). Cancer Causes Contr. 2003;14:131–8.

Blum A. Cancer prevention: preventing tobacco-related cancers. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. p. 545–57.

Khuri FR, Lee JJ, Lippman SM, Kim ES, Cooper JS, Benner SE, et al. Randomized phase III trial of low-dose isotretinoin for prevention of second primary tumors in stage I and II head and neck cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:441–50.

Cox LS, Africano NL, Tercyak KP, Taylor KL. Nicotine dependence treatment for patients with cancer. Cancer. 2003;98:632–44.

Richardson GE, Tucker MA, Venzon DJ, Linnoila RI, Phelps R, Phares JC, et al. Smoking cessation after successful treatment of small-cell lung cancer is associated with fewer smoking-related second primary cancers. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:383–90.

Tucker MA, Murray N, Shaw EG, Ettinger DS, Mabry M, Huber MH, et al. Second primary cancers related to smoking and treatment of small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Working Cadre. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1782–8.

Johnson BE. Second lung cancers in patients after treatment for an initial lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1335–45.

Kawahara M, Ushijima S, Kamimori T, Kodama N, Ogawara M, Matsui K, et al. Second primary tumours in more than 2-year disease-free survivors of small-cell lung cancer in Japan: the role of smoking cessation. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:409–12.

American Society for Clinical Oncology. Tobacco cessation and quality cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:2–5.

Gritz ER, Carr CR, Rapkin DA, Chang C, Beumer J, Ward PH. A smoking cessation intervention for head and neck cancer patients: trial design, patient accrual, and characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1991;1:67–73.

Gritz ER, Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, Mehta NV, Reece GP. Successes and failures of the teachable moment: smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:17–27.

Stanislaw AE, Wewers ME. A smoking cessation intervention with hospitalized surgical cancer patients: a pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 1994;17:81–6.

Griebel B, Wewers ME, Baker CA. The effectiveness of a nurse-managed minimal smoking-cessation intervention among hospitalized patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:897–902.

Wewers ME, Bowen JM, Stanislaw AE, Desimone VB. A nurse-delivered smoking cessation intervention among hospitalized postoperative patients—influence of a smoking-related diagnosis: a pilot study. Heart Lung. 1994;23:151–6.

Schnoll RA, James C, Malstrom M, Rothman RL, Wang H, Babb J, et al. Longitudinal predictors of continued tobacco use among patients diagnosed with cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:214–22.

Shields PG. Tobacco smoking, harm reduction, and biomarkers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1435–44.

Godtfredsen N, Prescott E, Osler M. Effect of smoking reduction on lung cancer risk. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294:1505–10.

Institute of Medicine. Clearing the smoke: assessing the science base for tobacco harm reduction. Institute of Medicine, Committee to Assess the Science Base for Tobacco Harm Reduction, Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention: Washington, DC; 2001.

Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ. Does smoking reduction increase future cessation and decrease disease risk? A qualitative review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:739–49.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data (BRFSS). 2008.

Substance Abuse, Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings, 2009. Rockvillle: Office of Applied Studies; 2009.

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27.

Biener L, Abrams DB. The contemplation ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10:360–5.

Maibach EW, Maxfield A, Ladin K, Slater M. Translating health psychology into effective health communication. J Health Psychol. 1996;1:261–7.

California Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Control Section, California Tobacco Survey: 1999. Jolla: Cancer Prevention and Control Unit; 1999.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Self change processes, self-efficacy and decisional balance across five stages of smoking cessation. Advances in Cancer Control—1983–1984. New York: Alan R. Liss; pp. 131–140.

Berg CJ, Thomas AN, Mertens AC, Schauer GL, Pinsker EA, Ahluwalia JS, et al. Correlates of continued smoking versus cessation among survivors of smoking-related cancers. Psychooncology. 2012; doi: 10.1002/pon.3077

Morgan DL, Krueger RA. The Focus Group Kit. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1998.

Patton M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Tobacco use among adults—United States 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1145–8.

Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:102–11.

Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Individual differences in adoption of treatment for smoking cessation: demographic and smoking history characteristics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:121–31.

Davis R, Rizwani W, Banerjee S, Kovacs M, Haura E, Coppola D, et al. Nicotine promotes tumor growth and metastasis in mouse models of lung cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7524.

National Cancer Institute. Risks Associated With Smoking Cigarettes With Low Machine-Measured Yields of Tar and Nicotine. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph 13. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2001.

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General 2004. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/smokingconsequences/index.html . Accessed 10 July 2012.

Augustine A, Harris RE, Wynder EL. Compensation as a risk factor for lung cancer in smokers who switch from nonfilter to filter cigarettes. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:188–91.

Stellman SD, Muscat JE, Hoffmann D, Wynder EL. Impact of filter cigarette smoking on lung cancer histology. Prev Med. 1997;26:451–6.

Hoffmann D, Hoffmann I. The changing cigarette, 1950–1995. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1997;50:307–64.

National Cancer Institute, Risks associated with smoking cigarettes with low machine-measured yields of tar and nicotine, in Smoking and tobacco control [Monograph 13]2002: Washington, DC.

Wennike P, Danielsson T, Landfeldt B, Westin A, Tønnesen P. Smoking reduction promotes smoking cessation: results from a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of nicotine gum with 2-year follow-up. Addiction. 2003;98:1395–402.

Asfar T, Ebbert JO, Klesges RC, Relyea GE. Do smoking reduction interventions promote cessation in smokers not ready to quit? Addict Behav. 2011;36:764–8.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Emory University Winship Cancer Institute Kennedy Seed Grant (PI: Berg) and the Georgia Cancer Coalition (PI: Berg).

Funding sources

This research was supported by the Emory University Winship Cancer Institute Kennedy Seed Grant (PI: Berg) and the Georgia Cancer Coalition (PI: Berg). Dr. Carpenter was supported by a Career Development Award from NIDA (K23 DA020482).

Financial disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berg, C.J., Carpenter, M.J., Jardin, B. et al. Harm reduction and cessation efforts and interest in cessation resources among survivors of smoking-related cancers. J Cancer Surviv 7, 44–54 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0243-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0243-9