Abstract

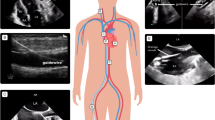

More than 250 continuous flow LVADs have been implanted in Japan during the last 3 years, with 1-year survival rates of 90 %. These excellent results cannot be achieved without VAD teams who know the detail of surgical techniques and perioperative management. Preoperative optimization of RV function is essential and intraoperative managements are focused on adequate balance between right and left ventricle to prevent right ventricular (RV) failure. For postoperative RV failure early institution of temporary RV mechanical support improves outcomes. Immediate CT scanning is crucial if LVAD patients complain of new neurological symptoms. When CT reveals cerebral hemorrhage, INR should be reduced as soon as possible. The driveline (DL) exit site remains a significant source of LVAD-related infections, and orientation and immobilization of the DL is important. Although vacuum assisted closure is useful to facilitate drainage and healing in pump pocket as well as DL infections, urgent heart transplantation, bridging to recovery, or pump exchange may become the only options to eradicate LVAD-related infections. Patients with continuous flow LVAD are more prone to developing de novo aortic insufficiency. Although majority of them can be managed medically, some require surgical intervention. The cause of pump thrombosis is multifactorial, including lowered INR and pump speed, and implantation techniques. It is important to exchange pumps in a timely manner either through a median sternotomy or subcostal incision in highly suspected patients indicated by elevated LDH and left-sided heart failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Deng MC, Edwards LB, Hertz MI, et al. Mechanical circulatory support device database of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: third annual report—2005. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1182–7.

Kormos RL, Teuteberg JJ, Pagani FD, et al. Right ventricular failure in patients with the HeartMate II continuous-flow left ventricular assist device: incidence, risk factors, and effect on outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:1316–24.

Fitzpatrick JR 3rd, Frederick JR, Hiesinger W, et al. Early planned institution of biventricular mechanical circulatory support results in improved outcomes compared with delayed conversion of a left ventricular assist device to a biventricular assist device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:971–7.

Fukui S, Matsumiya G, Toda K, et al. Recovery from hemorrhagic pulmonary damage by combined use of a left ventricular assist system and right ventricular assist system and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:248–50.

Saito S, Sakaguchi T, Miyagawa S, et al. Biventricular support using implantable continuous-flow ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:475–8.

Cohn WE, Gregoric ID, Frazier OH. Staged reoperation: a novel strategy for high-risk patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1558–9.

Stulak JM, Romans T, Cowger J, et al. Delayed sternal closure does not increase late infection risk in patients undergoing left ventricular assist device implantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:1115–9.

Slaughter MS, Naka Y, John R, et al. Post-operative heparin may not be required for transitioning patients with a HeartMate II left ventricular assist system to long-term warfarin therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:616–24.

Kormos RL, Holman WL. Adverse events and complications of mechanical circulatory support. Mechanical circulatory support. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2012. p. 165–82.

Masotti L, Di Napoli M, Godoy DA, et al. The practical management of intracerebral hemorrhage associated with oral anticoagulant therapy. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:228–40.

Huttner HB, Schellinger PD, Hartmann M, et al. Hematoma growth and outcome in treated neurocritical care patients with intracerebral hemorrhage related to oral anticoagulant therapy: comparison of acute treatment strategies using vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, and prothrombin complex concentrates. Stroke. 2006;37:1465–70.

Mehra MR, Stewart GC, Uber PA. The vexing problem of thrombosis in long-term mechanical circulatory support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:1–11.

Akhter SA, Ewald GA, Walsh MN, et al. Preliminary results for driveline site infection from the multicenter silicone-skin-interface (SSI) registry. Presented at ASAIO 2013.

Fleissner F, Avsar M, Malehsa D, Strueber M, Haverich A, Schmitto JD. Reduction of driveline infections through doubled driveline tunneling of left ventricular assist devices. Artif Organs. 2013;37:102–7.

Chinn R, Dembitsky W, Eaton L, et al. Multicenter experience: prevention and management of left ventricular assist device infections. ASAIO J. 2005;51:461–70.

Toda K, Yonemoto Y, Fujita T, et al. Risk analysis of bloodstream infection during long-term left ventricular assist device support. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:1387–93.

Gordon SM, Schmitt SK, Jacobs M, et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in patients with implantable left ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:725–30.

Baradarian S, Stahovich M, Krause S, Adamson R, Dembitsky W. Case series: clinical management of persistent mechanical assist device driveline drainage using vacuum-assisted closure therapy. ASAIO J. 2006;52:354–6.

Poston RS, Husain S, Sorce D, et al. LVAD bloodstream infections: therapeutic rationale for transplantation after LVAD infection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:914–21.

Yoshioka D, Toda K, Sakaguchi T, et al. Initial report of bridge to recovery in a patient with DuraHeart LVAD. J Artif Organs. 2013;16:386–8.

Nurozler F, Argenziano M, Oz MC, Naka Y. Fungal left ventricular assist device endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:614–8.

Robertson JO, Durrani AK, Mihaljevic T. Early failure of bioprostheses caused by adhesion of preserved leaflets after chordal-sparing mitral valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:1180–1.

Kitada S, Kato TS, Thomas SS, et al. Pre-operative echocardiographic features associated with persistent mitral regurgitation after left ventricular assist device implantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(9):897–904.

Park SJ, Liao KK, Segurola R, Madhu KP, Miller LW. Management of aortic insufficiency in patients with left ventricular assist devices: a simple coaptation stitch method (Park’s stitch). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:264–6.

Adamson RM, Dembitsky WP, Baradarian S, et al. Aortic valve closure associated with HeartMate left ventricular device support: technical considerations and long-term results. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:576–82.

Dembitsky W, Naka Y. Intraoperative management issues in mechanical circulatory support. Mechanical circulatory support. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2012. p. 153–64.

Atkins BZ, Hashmi ZA, Ganapathi AM, et al. Surgical correction of aortic valve insufficiency after left ventricular assist device implantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:1247–52.

D’Ancona G, Pasic M, Buz S, et al. TAVI for pure aortic valve insufficiency in a patient with a left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:e89–91.

Starling RC, Moazami N, Silvestry SC, et al. Unexpected abrupt increase in left ventricular assist device thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:33–40.

Sakaguchi T, Matsumiya G, Yoshioka D, et al. DuraHeart™ magnetically levitated left ventricular assist device: Osaka University experience. Circ J. 2013;77:1736–41.

Saito S, Yamazaki K, Nishinaka T, et al. Post-approval study of a highly pulsed, low-shear-rate, continuous-flow, left ventricular assist device, EVAHEART: a Japanese multicenter study using J-MACS. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(6):599–608.

Najjar SS, Slaughter MS, Pagani FD, et al. An analysis of pump thrombus events in patients in the HeartWare ADVANCE bridge to transplant and continued access protocol trial. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:23–34.

Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) analysis of pump thrombosis in the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:12–22.

Boyle AJ, Russell SD, Teuteberg JJ, et al. Low thromboembolism and pump thrombosis with the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device: analysis of outpatient anti-coagulation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:881–7.

Taghavi S, Ward C, Jayarajan SN, Gaughan J, Wilson LM, Mangi AA. Surgical technique influences HeartMate II left ventricular assist device thrombosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1259–65.

Shah P, Mehta VM, Cowger JA, Aaronson KD, Pagani FD. Diagnosis of hemolysis and device thrombosis with lactate dehydrogenase during left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:102–4.

Uriel N, Han J, Morrison KA, et al. Device thrombosis in HeartMate II continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: a multifactorial phenomenon. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:51–9.

Ota T, Yerebakan H, Akashi H, et al. Continuous-flow left ventricular assist device exchange: clinical outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:65–70.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This review was submitted at the invitation of the editorial committee.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toda, K., Sawa, Y. Clinical management for complications related to implantable LVAD use. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 63, 1–7 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-014-0480-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-014-0480-0