Abstract

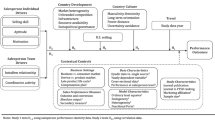

Cross-selling offers tremendous benefits for both vendors and customers. However, up to 75% of all cross-selling initiatives fail, usually for sales force–related reasons. Yet prior research has largely ignored the role of salespeople in the field of cross-selling. Using a motivation–opportunity–ability (MOA) framework, this research addresses factors that determine a salesperson’s cross-selling performance, including the predominant role of the selling team as a social environment in which individual behavior occurs. A dataset of 231 industrial salespeople working in 55 teams reveals that 37% of overall variation in behavior is caused by differences across teams. The team-specific hypotheses, based on social norms and reputation theory, are tested with a hierarchical linear modeling approach with matched data from three sources. Individual cross-selling motivation has a stronger effect when a selling team has strong cross-selling norms, and in the specific context of cross-selling, selling team reputation can constrain individual behavior that might damage that reputation. Salespeople also develop beliefs about the reasons for their team reputation, including its cross-selling ability, which can reduce an individual salesperson’s reputational concerns and hence reinforce individual cross-selling behavior. These results have significant theoretical and managerial implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out that research has distinguished groups and teams conceptually, such as according to the level of task interdependence (e.g., Chan 1998). From this perspective, members of groups are highly independent in their tasks, whereas members of teams are interdependent as they share collective effort and performance (Robbins et al. 2010). In other research, the term work group takes on a broader meaning (e.g., Hackman 1992; Kelly and Barsade 2001; Knippenberg et al. 2004), also embracing groups with high task interdependence among the members. The latter is consistent with a view broadly shared in team research, which defines a team as a task-specific or temporary group (e.g., Cohen and Bailey 1997; Moon and Armstrong 1994; Tyran and Gibson 2008). Following this view, we examine sales teams as a specific type of work group, in which there is at least moderate task interdependence among members. Thus, we use the terms work team and work group interchangeably when referring to sales teams, consistent with prior literature (e.g., Andersen and West 1998; Barrick et al. 1998; Chan 1998; Fiorelli 1988; Sundstrom et al. 1990).

The Herfindahl index is a common measure of concentration in economic literature (Tirole 1989). It also has proved useful in marketing for measuring competitive intensity (e.g., Luo et al. 2010; McAlister et al. 2007; Putsis and Bayus 2001), the structure of retailers’ brand portfolios (e.g., Ailawadi et al. 2006), consumers’ spending across stores (e.g., Goldman 1978), consumers’ product alternative choices (e.g., Nowlis et al. 2010), and firm revenue as either concentrated or spread over the customer portfolio (e.g., Yli-Renko and Janakiraman 2008). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to use the Herfindahl index to measure sales concentration across products in the context of personal selling.

References

Ahearne, M., MacKenzie, S., Podsakoff, P., Mathieu, J., & Lam, S. (2010). The role of consensus in sales team performance. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(3), 458–469.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Ailawadi, K. L., Harlam, B. A., César, J., & Trounce, D. (2006). Promotion Profitability for a Retailer: The Role of Promotion, Brand, Category, and Store Characteristics. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(6), 518–535.

Andersen, N. R., & West, M. A. (1998). Measuring Climate for Work Group Innovation: Development and Validation of the Team Climate Inventory. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19(3), 235–258.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1982). Some methods for respecifying measurement models to obtain unidimensional construct measurement. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 453–460.

Anderson, E., & Robertson, T. S. (1995). Inducing multiline salespeople to adopt house brands. Journal of Marketing, 59(April), 16–31.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402.

Atuahene-Gima, K. (1997). Adoption of new products by the sales force: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 14, 498–514.

Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., Neubert, M. J., & Mount, M. K. (1998). Relating Member Ability and Personality to Work-Team Processes and Team Effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(3), 377–391.

Bolton, R. N., Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2008). Expanding business-to-business customer relationships: Modeling the customer’s upgrade decision. Journal of Marketing, 72(1), 46–64.

Brown, S. P., & Peterson, R. A. (1994). The effect of effort on sales performance and job satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 58(2), 70–80.

Chan, D. (1998). Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 234–246.

Chatman, J. A. (1989). Improving Interactional Organizational Research: A Model of Person-Organization Fit. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 333–349.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16, 64–73.

Cohen, S. G., & Bailey, D. E. (1997). What makes teams work: Group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. Journal of Management, 23(3), 239–290.

Coyles, S., & Gokey, T. C. (2002). Customer retention is not enough. McKinsey Quarterly, 2, 81–89.

DeGabrielle, D. (2007). Cross-sell offer failure: Why does a 75 percent failure rate persist? CRM Magazine, www.destinationcrm.com.

Duclos, P., Luzardo, R., & Mirza, Y. H. (2007). Refocusing the sales force to cross-sell. McKinsey Quarterly, 7, 1–4.

Ehrhart, M. G., & Naumann, S. E. (2004). Organizational citizenship behavior in work groups: A group norms approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 960–974.

Fiorelli, J. S. (1988). Power in Work Groups: Team Member’s Perspectives. Human Relations, 41(1), 1–12.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(February), 39–50.

Fu, F., Richards, K., Hughes, D. E., & Jones, E. (2010). Motivating salespeople to sell new products: The relative influence of attitudes, subjective norms and self-efficacy. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 61–76.

Goldman, A. (1978). Confined Shopping Behavior Among Low Income Consumers: An Empirical Test. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(1), 11–19.

Guzzo, R. A., & Dickson, M. W. (1996). Teams in organizations: Recent research on performance and effectiveness. Annual Review of Psychology, 47(1), 307–338.

Hackman, J. R. (1992). Group influences on individuals in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 198–268). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Hartline, M. D., & Ferrell, O. C. (1996). The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 52–70.

Hartline, M. D., Maxham, J. G., III, & McKee, D. O. (2000). Corridors of influence in the dissemination of customer-oriented strategy to customer contact service employees. Journal of Marketing, 64(2), 35–50.

Helm, S., & Salminen, R. T. (2010). Basking in reflected glory: Using customer reference relationships to build reputation in industrial markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 39, 737–743.

Homburg, C., & Schäfer, H. (2001). Profitabilität durch Cross-Selling: Kundenpotentiale professionell erschließen. Mannheim: University of Mannheim.

Homburg, C., Wieseke, J., & Kuehnl, C. (2010). Social influence on salespeople’s adoption of sales technology: A multilevel analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(2), 159–168.

Jackson, J. (1975). Normative power and conflict potential. Sociological Methods and Research, 4, 237–263.

Kamakura, W. A. (2008). Cross-selling. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 6(3), 41–58.

Kamakura, W. A., Ramaswami, S. N., & Srivastava, R. K. (1991). Applying latent trait analysis in the evaluation of prospects for cross-selling of financial services. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 8, 329–349.

Kamakura, W. A., Wedel, M., de Rosa, F., & Mazzon, J. A. (2003). Cross-selling through database marketing: A mixed data factor analyzer for data augmentation and prediction. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 20, 45–65.

Kane, M. (2005). Why most cross-selling efforts flop. ABA Banking Journal, 97(2), 64–65.

Keiningham, T. L., Cooil, B., Aksoy, L., Andreassen, T. W., & Weiner, J. (2007). The value of different customer satisfaction and loyalty metrics in predicting customer retention, recommendation, and share-of-wallet. Managing Service Quality, 17(4), 361–384.

Kelly, J. R., & Barsade, S. G. (2001). Mood and Emotions in Small Groups and Work Teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), 99–130.

Kleinbaum, D. G., Kupper, L. L., Muller, K. E., & Nizam, A. (1998). Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods (3rd ed.). California: Duxbury.

Knippenberg, D., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Homan, A. C. (2004). Work Group Diversity and Group Performance: An Integrative Model and Research Agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 1008–1022.

Kumar, V., George, M., & Pancras, J. (2008). Cross-buying in retailing: Drivers and consequences. Journal of Retailing, 84(1), 15–27.

Li, S., Sun, B., & Wilcox, R. T. (2005). Cross-selling sequentially ordered products: An application to consumer banking services. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(2), 233–239.

Luo, X., Homburg, C., & Wieseke, J. (2010). Customer Satisfaction, Analyst Stock Recommendations, and Firm Value. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(6), 1041–1058.

MacInnis, D. J., Moorman, C., & Jaworski, B. J. (1991). Enhancing and measuring consumers’ motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from ads. Journal of Marketing, 55(5), 32–53.

Malms, O., & Schmitz, Ch. (2011). Cross-divisional orientation: Antecedents and effects on cross-selling success. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 18(3), 253–275.

McAlister, L., Srinivasan, R., & Kim, M. (2007). Advertising, Research and Development, and Systematic Risk of the Firm. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 35–48.

Merriam-Webster. (1996). Collegiate Dictionary (10th ed.). Springfield: Merriam-Webster.

Mohammed, S., & Dumville, B. C. (2001). Team mental models in a team knowledge framework: Expanding theory and measurement across disciplinary boundaries. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(2), 89–106.

Moon, M. A., & Armstrong, G. M. (1994). Selling teams: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 14(Winter), 17–30.

Moon, M. A., & Gupta, S. F. (1997). Examining the formation of selling centers: A conceptual framework. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 18(2), 31–41.

Moorman, M. B., & Albrecht, C. (2008). Team selling: Getting incentive compensation right. Velocity, 10(2), 33–37.

Mulki, J. P., Lassk, F. G., & Jaramillo, F. (2008). The effect of self-efficacy on salesperson work overload and pay satisfaction. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 28(3), 285–297.

Netessine, S., Savin, S., & Xiao, W. (2006). Revenue management through dynamic cross-selling in e-commerce retailing. Operations Research, 54(5), 893–913.

Ngobo, P. V. (2004). Drivers of customers’ cross-buying intentions. European Journal of Marketing, 38(9/10), 1129–1157.

Nowlis, S. M., Dhar, R., & Simonson, I. (2010). The Effect of Decision Order on Purchase Quantity Decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(4), 725–737.

Plouffe, C. R., & Barclay, D. W. (2007). Salesperson navigation: The intraorganizational dimension of the sales role. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(4), 528–539.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. M., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method variance in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Putsis, W. P., & Bayus, B. L. (2001). An Empirical Analysis of Firms’ Product Line Decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(1), 110–l18.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2dth ed.). Newbury Park: Sage.

Reinartz, W., Krafft, M., & Hoyer, W. D. (2004). The customer relationship management process: Its measurement and impact on performance. Journal of Marketing Research, 41(August), 293–305.

Rentsch, J. R., & Steel, R. P. (2003). What does unit-level absence mean? Issues for future unit-level absence research. Human Resource Management Review, 13, 185–202.

Robbins, S. P., Judge, T. A., & Campbell, T. T. (2010). Organizational Behaviour. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Rothschild, M. L. (1999). Carrots, sticks, and promises: A conceptual framework for the management of public health and social issue behaviors. Journal of Marketing, 63(5), 24–37.

Schäfer, H. (2002). Die Erschließung von Kundenpotentialen durch Cross-Selling. Doctoral thesis, University of Mannheim, Wiesbaden: DUV.

Shamir, B. (1991). Meaning, self and motivation in organizations. Organization Studies, 12(3), 405–424.

Siemsen, E., Roth, A. V., & Balasubramanian, S. (2008). How motivation, opportunity, and ability drive knowledge sharing: The constraining-factor model. Journal of Operations Management, 26, 426–445.

Smith, J. B., & Barclay, D. W. (1993). Team selling effectiveness: A small group perspective. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 1(2), 3–32.

Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., De Jong, M. G., & Baumgartner, H. (2010). Socially desirable response tendencies in survey research. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(April), 199–214.

Sujan, H., Weitz, B. A., & Kumar, N. (1994). Learning orientation, working smart, and effective selling. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 39–52.

Sundstrom, E., De Meuse, K. E., & Futrell, D. (1990). Work Teams: Applications and Effectiveness. American Psychologist, 45(2), 120–133.

Tirole, J. (1989). The Theory of Industrial Organization. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Tuli, K. R., Kohli, A. K., & Bharadwaj, S. G. (2007). Rethinking customer solutions: From product bundles to relational processes. Journal of Marketing, 71(3), 1–17.

Tyran, K. L., & Gibson, C. B. (2008). Is what you see, what you get? The relationship among surface- and deep-level heterogeneity characteristics, group efficacy, and team reputation. Group & Organization Management, 33(1), 46–76.

Weiss, A. M., Anderson, E., & MacInnis, D. J. (1999). Reputation management as a motivation for sales structure decisions. Journal of Marketing, 63(October), 74–89.

Weitz, B. A., Sujan, H., & Sujan, M. (1986). Knowledge, motivation, and adaptive behavior: A framework for improving selling effectiveness. Journal of Marketing, 50(October), 174–191.

Wiedmann, K.-P., Klee, A., & Siemon, N. (2003). Kundenmanagement im Privatkundengeschäft von Kreditinstituten. Hannover: University of Hannover.

Wieseke, J., Homburg, Ch, & Lee, N. (2008). Understanding the adoption of new brands through salespeople: A multilevel framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36, 278–291.

Yli-Renko, H., & Janakiraman, R. (2008). How Customer Portfolio Affects New Product Development in Technology-Based Entrepreneurial Firms. Journal of Marketing, 72(September), 131–148.

Acknowledgement

I thank Christian Belz and Gary L. Lilien for insightful discussions, and Hans Baumgartner, Shankar Ganesan, Frank Germann, Simon de Jong, Jan Landwehr, and Daniel Wentzel for many helpful comments on previous drafts of this paper. Also, I gratefully acknowledge the constructive guidance of the four anonymous JAMS reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

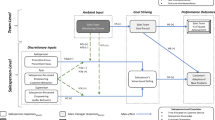

Hierarchical models

Model 1

Model 2

Model 3

Model 4

Regression model

where salespeople i = 1−n, PER = cross-selling performance, PPA = product portfolio adoption, CDO = cross-divisional orientation, and RES = resource availability.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schmitz, C. Group influences of selling teams on industrial salespeople’s cross-selling behavior. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 41, 55–72 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0304-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0304-7